Race and intelligence: Difference between revisions

m →Heritability within and between groups: Cite cleanup |

m →Socioeconomic environment: Cite cleanup |

||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

===Socioeconomic environment=== |

===Socioeconomic environment=== |

||

Different aspects of the socioeconomic environment in which children are raised have been shown to correlate with part of the IQ gap, but they do not account for the entire gap.{{sfn|Hunt|2010|page=428}} According to a 2006 review, these factors account for slightly less than half of one standard deviation of the gap.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Magnuson|first1=Katherine A.|last2=Duncan|first2=Greg J.|title=The role of family socioeconomic resources in the black–white test score gap among young children|journal=[[Developmental Review]]|date=December 2006|volume=26|issue=4|pages=365–399|doi=10.1016/j.dr.2006.06.004}}</ref> Generally the difference between mean test scores of black people and white people is not eliminated when individuals and groups are matched on socioeconomic status (SES), suggesting that the relationship between IQ and SES is not simply one in which SES determines IQ. Rather it may be the case that differences in intelligence, particularly parental intelligence, may also cause differences in SES, making separating the two factors difficult. |

Different aspects of the socioeconomic environment in which children are raised have been shown to correlate with part of the IQ gap, but they do not account for the entire gap.{{sfn|Hunt|2010|page=428}} According to a 2006 review, these factors account for slightly less than half of one standard deviation of the gap.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Magnuson|first1=Katherine A.|last2=Duncan|first2=Greg J.|title=The role of family socioeconomic resources in the black–white test score gap among young children|journal=[[Developmental Review]]|date=December 2006|volume=26|issue=4|pages=365–399|doi=10.1016/j.dr.2006.06.004}}</ref> Generally the difference between mean test scores of black people and white people is not eliminated when individuals and groups are matched on socioeconomic status (SES), suggesting that the relationship between IQ and SES is not simply one in which SES determines IQ. Rather it may be the case that differences in intelligence, particularly parental intelligence, may also cause differences in SES, making separating the two factors difficult.{{sfn|Neisser|Boodoo|Bouchard|Boykin|1996}} {{harvtxt|Hunt|2010|page=428}} summarises data {{clarify|date = December 2015|reason = which research?}} showing that, jointly, SES and parental IQ account for the full gap (in populations of young children, after controlling parental IQ and parental SES, the gap is not statistically different from zero). He argues the SES-linked components reflect parental occupation status, mother's verbal comprehension score and parent-child interaction quality. Hunt also reviews data showing that the correlation between home environment and IQ becomes weaker with age.{{citation needed|date=December 2015}} Hart and Risley argue that in welfare, working-class, and professional families, children hear a large disparity in the amount of language (between 13 million and 45 million words) in the age range of 0–3, and that by age 9 these differences lead to large differences in child outcomes.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Hart|first1=Betty|last2=Risley|first2=Todd|title=Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children|publisher=Brookes Publishing, Baltimore, Maryland, USA|year=1995}}</ref> |

||

Other research has focussed on different causes of variation within low SES and high SES groups.<ref name="Scarr-Salapatek1971">{{cite journal | last1 = Scarr-Salapatek | first1 = S. | year = 1971 | title = Race, social class, and IQ. | url = | journal = Science | volume = 174 | issue = 4016| pages = 1285–95 | doi=10.1126/science.174.4016.1285| pmid = 5167501 | bibcode = 1971Sci...174.1285S}}</ref><ref name="Scarr-Salapatek1974">{{cite journal | last1 = Scarr-Salapatek | first1 = S. | year = 1974 | title = Some myths about heritability and IQ. | doi = 10.1038/251463b0 | journal = Nature | volume = 251 | issue = 5475| pages = 463–464 | bibcode = 1974Natur.251..463S }}</ref><ref name="Rowe1994">D. C. Rowe. (1994). ''The Limits of Family Influence: Genes, Experience and Behaviour''. Guilford Press. London</ref> |

Other research has focussed on different causes of variation within low SES and high SES groups.<ref name="Scarr-Salapatek1971">{{cite journal | last1 = Scarr-Salapatek | first1 = S. | year = 1971 | title = Race, social class, and IQ. | url = | journal = Science | volume = 174 | issue = 4016| pages = 1285–95 | doi=10.1126/science.174.4016.1285| pmid = 5167501 | bibcode = 1971Sci...174.1285S}}</ref><ref name="Scarr-Salapatek1974">{{cite journal | last1 = Scarr-Salapatek | first1 = S. | year = 1974 | title = Some myths about heritability and IQ. | doi = 10.1038/251463b0 | journal = Nature | volume = 251 | issue = 5475| pages = 463–464 | bibcode = 1974Natur.251..463S }}</ref><ref name="Rowe1994">D. C. Rowe. (1994). ''The Limits of Family Influence: Genes, Experience and Behaviour''. Guilford Press. London</ref> |

||

Revision as of 04:48, 6 March 2020

A request that this article title be changed to Race and intelligence myth is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The connection between race and intelligence has been a subject of debate in both popular science and academic research since the inception of IQ testing in the early 20th century. Since then, there have been observed differences between average IQ scores of different population groups, but whether and to what extent these differences reflect environmental factors as opposed to genetic ones, as well as what the definitions of "race" and "intelligence" are, and whether they can be objectively defined, is the subject of much debate. At present, there is no evidence that these differences in test scores have a genetic component.

The first tests showing differences in IQ scores between different population groups in the United States were the tests of United States Army recruits in World War I. In the 1920s, groups of eugenics lobbyists argued that this demonstrated that African-Americans and certain immigrant groups were of inferior intellect to Anglo-Saxon white people, due to innate biological differences, using this as an argument for policies of racial segregation. However, soon, other studies appeared, contesting these conclusions and arguing instead that the Army tests had not adequately controlled for environmental factors, such as socio-economic and educational inequality between black people and white people. Later observations of phenomena such as the Flynn effect have also suggested that environmental factors play a greater role in group IQ differences than previously expected.

The causes of differences in IQ test scores are not well-understood, and the topic remains controversial among researchers.

History of the debate

Claims of races having different intelligence were used to justify colonialism, slavery, racism, social Darwinism, and racial eugenics. Racial thinkers such as Arthur de Gobineau relied crucially on the assumption that black people were innately inferior to white people in developing their ideologies of white supremacy. Even enlightenment thinkers such as Thomas Jefferson, a slave owner, believed black people to be innately inferior to white people in physique and intellect.[1]

Early IQ testing

The first practical intelligence test was developed between 1905 and 1908 by Alfred Binet in France for school placement of children. Binet warned that results from his test should not be assumed to measure innate intelligence or used to label individuals permanently.[2] Binet's test was translated into English and revised in 1916 by Lewis Terman (who introduced IQ scoring for the test results) and published under the name the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales. As Terman's test was published, there was great concern in the United States about the abilities and skills of recent immigrants. Different immigrant nationalities were sometimes thought to belong to different races, such as Slavs. A different set of tests developed by Robert Yerkes were used to evaluate draftees for World War I, and researchers found that people from southern and eastern Europe scored lower than native-born Americans, that Americans from northern states had higher scores than Americans from southern states, and that black Americans scored lower than white Americans.[3] The results were widely publicized by a lobby of anti-immigration activists, including the New York patrician and conservationist Madison Grant, who considered the Nordic race to be superior, but under threat of immigration by inferior breeds. In his influential work, A Study of American Intelligence, psychologist Carl Brigham used the results of the Army tests to argue for a stricter immigration policy, limiting immigration to countries considered to belong to the "Nordic race".[4]

In the 1920s, states like Virginia enacted eugenic laws, such as its 1924 Racial Integrity Act, which established the one-drop rule as law. Many scientists reacted negatively to eugenicist claims linking abilities and moral character to racial or genetic ancestry. They pointed to the contribution of environment to test results (such as speaking English as a second language).[5] By the mid-1930s, many United States psychologists adopted the view that environmental and cultural factors played a dominant role in IQ test results, among them Carl Brigham, who repudiated his own previous arguments on the grounds that he realized that the tests were not a measure of innate intelligence. Discussion of the issue in the United States also influenced German Nazi claims of the "Nordics" being a "master race", influenced by Grant's writings.[6] As the American public sentiment shifted against the Germans, claims of racial differences in intelligence increasingly came to be regarded as problematic.[7] Anthropologists such as Franz Boas, and Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish, did much to demonstrate the unscientific status of many of the claims about racial hierarchies of intelligence.[8] Nonetheless, a powerful eugenics and segregation lobby funded largely by textile-magnate Wickliffe Draper continued to publicize studies using intelligence studies as an argument for eugenics, segregation, and anti-immigration legislation.[9]

Pioneer Fund and The Bell Curve

As the de-segregation of the American South gained traction in the 1950s, debate about black intelligence resurfaced. Audrey Shuey, funded by Draper's Pioneer Fund, published a new analysis of Yerkes' tests, concluding that black people really were of inferior intellect to white people. This study was used by segregationists as an argument that it was to the advantage of black children to be educated separately from the superior white children.[10] In the 1960s, the debate was further revived when William Shockley publicly defended the argument that black children were innately unable to learn as well as white children.[11] Arthur Jensen caused discussion of the issue with his Harvard Educational Review article, "How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?", questioning remedial education for African-American children. He suggested their poor educational performance reflected an underlying genetic cause rather than lack of stimulation at home.[12][13]

Another revival of public debate followed the appearance of The Bell Curve (1994), a book by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray, who strongly emphasized the societal effects of low IQ (focusing in most chapters strictly on the non-Hispanic white population of the United States).[14] In 1994, a group of 52 researchers (mostly psychologists) signed an editorial statement "Mainstream Science on Intelligence" in response to the book. The Bell Curve also led to a 1995 report from the American Psychological Association, "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns", acknowledging a difference between mean IQ scores of white people and black people as well as the absence of any adequate explanation of it, either environmental or genetic. The Bell Curve prompted the publication of several multiple-author books responding from a variety of points of view.[15][16] They include The Bell Curve Debate (1995), Inequality by Design: Cracking the Bell Curve Myth (1996) and a second edition of The Mismeasure of Man (1996) by Stephen Jay Gould.[16]

Some of the authors proposing genetic explanations for group differences have received funding from the Pioneer Fund, which was headed by J. Philippe Rushton until his death in 2012.[9][16][17][18][19] The Southern Poverty Law Center lists the Pioneer Fund as a hate group, citing the fund's history, its funding of race and intelligence research, and its connections with racist individuals.[20] Other researchers have criticized the Pioneer Fund for promoting scientific racism, eugenics and white supremacy.[9][21][22][23]

Criticisms of validity of race and IQ

Intelligence, IQ, g and IQ tests

The concept of intelligence and the degree to which intelligence is measurable is a matter of debate. While there is some consensus about how to define intelligence, it is not universally accepted that it is something that can be unequivocally measured by a single figure.[24] A recurring criticism is that different societies value and promote different kinds of skills and that the concept of intelligence is therefore culturally variable and cannot be measured by the same criteria in different societies.[24] Consequently, some critics argue that proposed relationships to other variables are necessarily tentative.[25]

In relation to the study of racial differences in IQ test scores, it becomes a crucial question of what exactly it is that IQ tests measure. Arthur Jensen was a proponent of the view that there is a correlation between scores on all the known types of IQ tests, and that this correlation points to an underlying factor of general intelligence, or g. In most conceptions of g, it is considered to be fairly fixed in a given individual and unresponsive to training or other environmental influences. In this view, test score differences, especially in those tasks considered to be particularly "g-loaded", reflect the test taker's innate capability.

Other psychometricians argue that, while there may or may not be a general intelligence factor, performance on tests relies crucially on knowledge acquired through prior exposure to the types of tasks that such tests contain. This view would mean that tests cannot be expected to reflect only the innate abilities of a given individual, because the expression of potential will always be mediated by experience and cognitive habits. It also means that comparison of test scores from persons with widely different life experiences and cognitive habits is not an expression of their relative innate potentials.[26]

Race

The majority of anthropologists today consider race to be a sociopolitical phenomenon rather than a biological one,[27] a view supported by considerable genetics research.[28][29] The current mainstream view in the social sciences and biology is that race is a social construction based on folk ideologies that construct groups based on social disparities and superficial physical characteristics.[30] Sternberg, Grigorenko & Kidd (2005) state, "Race is a socially constructed concept, not a biological one. It derives from people's desire to classify."[25] The concept of human "races" as natural and separate divisions within the human species has also been rejected by the American Anthropological Association. The official position of the AAA, adopted in 1998, is that advances in scientific knowledge have made it "clear that human populations are not unambiguous, clearly demarcated, biologically distinct groups" and that "any attempt to establish lines of division among biological populations [is] both arbitrary and subjective."[31]

Race in studies of human intelligence is almost always determined using self-reports, rather than based on analyses of the genetic characteristics of the tested individuals. According to psychologist David Rowe, self-report is the preferred method for racial classification in studies of racial differences because classification based on genetic markers alone ignore the "cultural, behavioral, sociological, psychological, and epidemiological variables" that distinguish racial groups.[32] Hunt and Carlson write that "Nevertheless, self-identification is a surprisingly reliable guide to genetic composition. Tang et al. (2005) applied mathematical clustering techniques to sort genomic markers for over 3,600 people in the United States and Taiwan into four groups. There was almost perfect agreement between cluster assignment and individuals' self-reports of racial/ethnic identification as white, black, East Asian, or Latino."[33] Sternberg and Grigorenko disagree with Hunt and Carlson's interpretation of Tang, "Tang et al.'s point was that ancient geographic ancestry rather than current residence is associated with self-identification and not that such self-identification provides evidence for the existence of biological race."[34]

Anthropologist C. Loring Brace[35] and geneticist Joseph Graves disagree with the idea that cluster analysis and the correlation between self-reported race and genetic ancestry support biological race.[36] They argue that while it is possible to find biological and genetic variation corresponding roughly to the groupings normally defined as races, this is true for almost all geographically distinct populations. The cluster structure of the genetic data is dependent on the initial hypotheses of the researcher and the populations sampled. When one samples continental groups, the clusters become continental; if one had chosen other sampling patterns, the clusters would be different. Kaplan 2011 therefore concludes that, while differences in particular allele frequencies can be used to identify populations that loosely correspond to the racial categories common in Western social discourse, the differences are of no more biological significance than the differences found between any human populations (e.g., the Spanish and Portuguese).

Earl B. Hunt agrees that racial categories are defined by social conventions, though he points out that they also correlate with clusters of both genetic traits and cultural traits. Hunt explains that, due to this, racial IQ differences are caused by these variables that correlate with race, and race itself is rarely a causal variable. Researchers who study racial disparities in test scores are studying the relationship between the scores and the many race-related factors which could potentially affect performance. These factors include health, wealth, biological differences, and education.[37]

Group differences

The study of human intelligence is one of the most controversial topics in psychology. It remains unclear whether group differences in intelligence test scores are caused by heritable factors or by "other correlated demographic variables such as socioeconomic status, education level, and motivation."[38] Hunt and Carlson outlined four contemporary positions on differences in IQ based on race or ethnicity. The first is that these reflect real differences in average group intelligence, which is caused by a combination of environmental factors and heritable differences in brain function. A second position is that differences in average cognitive ability between races are caused entirely by social and/or environmental factors. A third position holds that differences in average cognitive ability between races do not exist, and that the differences in average test scores are the result of inappropriate use of the tests themselves. Finally, a fourth position is that either or both of the concepts of race and general intelligence are poorly constructed and therefore any comparisons between races are meaningless.[33]

Test scores

In the US, generally, individuals identifying themselves as Asian tend to score higher on IQ tests than do Caucasians, who score higher than Hispanics, who score higher than African Americans. Nevertheless, greater variation in IQ scores exists within each ethnic group than between them.[39]

In response to the controversial 1994 book The Bell Curve, the American Psychological Association (APA) formed a task-force of eleven experts, which issued a report, "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" in 1995. Regarding group differences, the report reaffirmed the consensus that differences within groups are much wider than difference between groups, and that that claims of ethnic difference in intelligence should be scrutinized carefully, as this had been used to justify racial discrimination. It also acknowledged limitations in the racial categories used, as these categories are neither consistently applied, nor homogeneous (see also race and ethnicity in the United States).[40]

Roth et al. (2001), in a review of the results of a total of 6,246,729 participants on other tests of cognitive ability or aptitude, found a difference in mean IQ scores between black people and white people of 1.1 SD. Consistent results were found for college and university application tests such as the Scholastic Aptitude Test (N = 2.4 million) and Graduate Record Examination (N = 2.3 million), as well as for tests of job applicants in corporate sections (N = 0.5 million) and in the military (N = 0.4 million).[41] According to the same study, East Asians have tended to score relatively higher on visuospatial subtests with lower scores in verbal subtests while Ashkenazi Jews score higher in verbal subtests with lower scores in visuospatial subtests. The few Amerindian populations who have been systematically tested, including Arctic Natives, tend to score worse on average than white populations but better on average than black populations.[41][dubious – discuss]

The racial groups studied in the United States and Europe are not necessarily representative samples for populations in other parts of the world. Cultural differences may also factor in IQ test performance and outcomes. Therefore, results in the United States and Europe do not necessarily correlate to results in other populations.[42]

Flynn effect and the closing gap

For the past century raw scores on IQ tests have been rising; this score increase is known as the "Flynn effect", named after James R. Flynn. In the United States, the increase was continuous and approximately linear from the earliest years of testing to about 1998 when the gains stopped and some tests even showed decreasing test scores. For example, in the United States the average scores of black people on some IQ tests in 1995 were the same as the scores of white people in 1945.[43] As one pair of academics phrased it, "the typical African American today probably has a slightly higher IQ than the grandparents of today's average white American."[44]

Flynn has argued that given that these changes take place between one generation and the next it is highly unlikely that genetic factors could account for the increasing scores, which must then be caused by environmental factors. The Flynn Effect has often been used as an argument that the racial gap in IQ test scores must be environmental too, but this is not generally agreed – others have asserted that the two may have entirely different causes. A meta-analysis by Te Nijenhuis and van der Flier (2013) concluded that the Flynn effect and group differences in intelligence were likely to have different causes. They stated that the Flynn effect is caused primarily by environmental factors and that it's unlikely these same environmental factors play an important role in explaining group differences in IQ.[45] The importance of the Flynn effect in the debate over the causes for the IQ gap lies in demonstrating that environmental factors may cause changes in test scores on the scale of 1 SD. This had previously been doubted.

A separate phenomenon from the Flynn effect has been the discovery that the IQ gap has been gradually closing over the last decades of the 20th century, as black test-takers increased their average scores relative to white test-takers. For instance, Vincent reported in 1991 that the black-white IQ gap was decreasing among children, but that it was remaining constant among adults.[46] Similarly, a 2006 study by Dickens and Flynn estimated that the difference between mean scores of black people and white people closed by about 5 or 6 IQ points between 1972 and 2002,[47] a reduction of about one-third. In the same period, the educational achievement disparity also diminished.[48] In a 2006 study, Murray agreed with Dickens and Flynn that there has been a narrowing of the difference; "Dickens' and Flynn's estimate of 3–6 IQ points from a base of about 16–18 points is a useful, though provisional, starting point". But he argued that this has stalled and that there has been no further narrowing for people born after the late 1970s.[49] A subsequent study by Murray, based on the Woodcock–Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities, estimated that the black-white IQ difference decreased by about one-half of one standard deviation from those born in the 1920s to those born in the second half of the 1960s and early 1970s.[50] Recent reviews by Flynn and Dickens (2006), Mackintosh (2011), and Nisbett et al. 2012 accept the gradual closing of the gap as a fact. In his review of the historical trends, Hunt (2010, p. 411) states: "There is some variety in the results, but not a great deal. The African American means are about 1 standard deviation unit (15 points on the IQ scale) below the white means, and the Hispanic means fall in between."

Some studies reviewed by Hunt (2010, p. 418) found that rise in the average achievement of African Americans was caused by a reduction in the number of African American students in the lowest range of scores without a corresponding increase in the number of students in the highest ranges. A 2012 review of the literature found that the IQ gap had diminished by 0.33 standard deviations since first reported.[51][52]

A 2013 analysis of the National Assessment of Educational Progress found that from 1971 to 2008, the size of the black–white IQ gap in the United States decreased from 16.33 to 9.94 IQ points. It has also concluded however that, while IQ means are continuing to rise in all ethnic groups, this growth is occurring more slowly among 17-year-old students than among younger students and the black-white IQ gap is no longer narrowing. As of 2008, a study published in 2013 by Heiner Rindermann, Stefan Pinchelmann, and James Thompson have estimated the IQ means of 17-year-old black, white, and Hispanic students to range respectively from 90.45–94.15, 102.29–104.57 and 92.30–95.90 points. They explain that the gap may persist due to the crack epidemic, the degradation of African-American family structure, the rise of fraud in the educational system (especially with respect to No Child Left Behind), the decrease in unskilled real wages and employment among African-Americans due to globalization and minimum wage increases, differences in parental practices (such as breastfeeding or reading to children), and "environmental conditions shaped by [African-Americans] themselves." To resolve this, they ultimately recommend the reestablishment of "meritoric principles" and "blindly graded objective central exams," as opposed to "ethnically based policies," in education.[53][54]

Environmental influences on group differences in IQ

The following environmental factors are some of those suggested as explaining a portion of the differences in average IQ between races. These factors are not mutually exclusive with one another, and some may, in fact, contribute directly to others. Furthermore, the relationship between genetics and environmental factors may be complicated. For example, the differences in socioeconomic environment for a child may be due to differences in genetic IQ for the parents, and the differences in average brain size between races could be the result of nutritional factors.[40]

Health and nutrition

Environmental factors including childhood lead exposure,[55] low rates of breast feeding,[57] and poor nutrition[58][59] can significantly affect cognitive development and functioning. For example, childhood exposure to lead, associated with homes in poorer areas[60] causes an average IQ drop of 7 points,[61] and iodine deficiency causes a fall, on average, of 12 IQ points.[62][63] Such impairments may sometimes be permanent, sometimes be partially or wholly compensated for by later growth. The first two years of life is the critical time for malnutrition, the consequences of which are often irreversible and include poor cognitive development, educability, and future economic productivity.[64] The African American population of the United States is statistically more likely to be exposed to many detrimental environmental factors such as poorer neighborhoods, schools, nutrition, and prenatal and postnatal health care.[65][66] Mackintosh points out that for American black people infant mortality is about twice as high as for white people, and low birthweight is twice as prevalent. At the same time white mothers are twice as likely to breastfeed their infants, and breastfeeding is highly correlated with IQ for low birthweight infants. In this way a wide number of health related factors that influence IQ are unequally distributed between the two groups.[67]

The Copenhagen consensus in 2004 stated that lack of both iodine and iron has been implicated in impaired brain development, and this can affect enormous numbers of people: it is estimated that one-third of the total global population are affected by iodine deficiency. In developing countries, it is estimated that 40% of children aged four and under suffer from anaemia because of insufficient iron in their diets.[68]

Other scholars have found that simply the standard of nutrition has a significant effect on population intelligence, and that the Flynn effect may be caused by increasing nutrition standards across the world.[69] James Flynn has himself argued against this view.[70]

Some recent research has argued that the retardation caused in brain development by infectious diseases, many of which are more prevalent in non-white populations, may be an important factor in explaining the differences in IQ between different regions of the world.[71] The findings of this research, showing the correlation between IQ, race and infectious diseases was also shown to apply to the IQ gap in the US, suggesting that this may be an important environmental factor.[72]

A 2013 meta-analysis by the World Health Organization found that, after controlling for maternal IQ, breastfeeding was associated with IQ gains of 2.19 points. The authors suggest that this relationship is causal but state that the practical significance of this gain is debatable; however, they highlight one study suggesting an association between breastfeeding and academic performance in Brazil, where "breastfeeding duration does not present marked variability by socioeconomic position."[73] Colen and Ramey (2014) similarly find that controlling for sibling comparisons within families, rather than between families, reduces the correlation between breastfeeding status and WISC IQ scores by nearly a third, but further find the relationship between breastfeeding duration and WISC IQ scores to be insignificant. They suggest that "much of the beneficial long-term effects typically attributed to breastfeeding, per se, may primarily be due to selection pressures into infant feeding practices along key demographic characteristics such as race and socioeconomic status."[74] Reichman estimates that no more than 3 to 4% of the black-white IQ gap can be explained by black-white disparities in low birth weight.[75]

Education

Several studies have proposed that a large part of the gap can be attributed to differences in quality of education.[76] Racial discrimination in education has been proposed as one possible cause of differences in educational quality between races.[77] According to a paper by Hala Elhoweris, Kagendo Mutua, Negmeldin Alsheikh and Pauline Holloway, teachers' referral decisions for students to participate in gifted and talented educational programs were influenced in part by the students' ethnicity.[78]

The Abecedarian Early Intervention Project, an intensive early childhood education project, was also able to bring about an average IQ gain of 4.4 points at age 21 in the black children who participated in it compared to controls.[57] Arthur Jensen agreed that the Abecedarian project demonstrates that education can have a significant effect on IQ, but also said that no educational program thus far has been able to reduce the black-white IQ gap by more than a third, and that differences in education are thus unlikely to be its only cause.[79]

A series of studies by Joseph Fagan and Cynthia Holland measured the effect of prior exposure to the kind of cognitive tasks posed in IQ tests on test performance. Assuming that the IQ gap was the result of lower exposure to tasks using the cognitive functions usually found in IQ tests among African American test takes, they prepared a group of African Americans in this type of tasks before taking an IQ test. The researchers found that there was no subsequent difference in performance between the African-Americans and white test takers.[80][81] Daley and Onwuegbuzie conclude that Fagan and Holland demonstrate that "differences in knowledge between black people and white people for intelligence test items can be erased when equal opportunity is provided for exposure to the information to be tested".[82] A similar argument is made by David Marks who argues that IQ differences correlate well with differences in literacy suggesting that developing literacy skills through education causes an increase in IQ test performance.[83][84]

A 2003 study found that two variables — stereotype threat and the degree of educational attainment of children's fathers — partially explained the black-white gap in cognitive ability test scores, undermining the hereditarian view that they stemmed from immutable genetic factors.[85]

Socioeconomic environment

Different aspects of the socioeconomic environment in which children are raised have been shown to correlate with part of the IQ gap, but they do not account for the entire gap.[86] According to a 2006 review, these factors account for slightly less than half of one standard deviation of the gap.[87] Generally the difference between mean test scores of black people and white people is not eliminated when individuals and groups are matched on socioeconomic status (SES), suggesting that the relationship between IQ and SES is not simply one in which SES determines IQ. Rather it may be the case that differences in intelligence, particularly parental intelligence, may also cause differences in SES, making separating the two factors difficult.[40] Hunt (2010, p. 428) summarises data [clarification needed] showing that, jointly, SES and parental IQ account for the full gap (in populations of young children, after controlling parental IQ and parental SES, the gap is not statistically different from zero). He argues the SES-linked components reflect parental occupation status, mother's verbal comprehension score and parent-child interaction quality. Hunt also reviews data showing that the correlation between home environment and IQ becomes weaker with age.[citation needed] Hart and Risley argue that in welfare, working-class, and professional families, children hear a large disparity in the amount of language (between 13 million and 45 million words) in the age range of 0–3, and that by age 9 these differences lead to large differences in child outcomes.[88]

Other research has focussed on different causes of variation within low SES and high SES groups.[89][90][91] In the US, among low-SES groups, genetic differences account for a smaller proportion variance in IQ than among higher SES populations.[92] Such effects are predicted by the bioecological hypothesis – that genotypes are transformed into phenotypes through nonadditive synergistic effects of the environment.[93] Nisbett et al. (2012a) suggest that high SES individuals are more likely to be able to develop their full biological potential, whereas low SES individuals are likely to be hindered in their development by adverse environmental conditions. The same review also points out that adoption studies generally are biased towards including only high and high middle SES adoptive families, meaning that they will tend to overestimate average genetic effects. They also note that studies of adoption from lower-class homes to middle-class homes have shown that such children experience a 12–18 pt gain in IQ relative to children who remain in low SES homes.[51] A 2015 study found that environmental factors (namely, family income, maternal education, maternal verbal ability/knowledge, learning materials in the home, parenting factors (maternal sensitivity, maternal warmth and acceptance, and safe physical environment), child birth order, and child birth weight) accounted for the black-white gap in cognitive ability test scores.[94]

Test bias

A number of studies have reached the conclusion that IQ tests may be biased against certain groups.[95][96][97][98] The validity and reliability of IQ scores obtained from outside the United States and Europe have been questioned, in part because of the inherent difficulty of comparing IQ scores between cultures.[99][100] Several researchers have argued that cultural differences limit the appropriateness of standard IQ tests in non-industrialized communities.[101][102]

A 1996 report by the American Psychological Association states that intelligence can be difficult to compare across cultures, and notes that differing familiarity with test materials can produce substantial differences in test results; it also says that tests are accurate predictors of future achievement for black and white Americans, and are in that sense unbiased.[40] The view that tests accurately predict future educational attainment is reinforced by Nicholas Mackintosh in his 1998 book IQ and Human Intelligence,[103] and by a 1999 literature review by Brown, Reynolds & Whitaker (1999).

James R. Flynn, surveying studies on the topic, notes that the weight and presence of many test questions depends on what sorts of information and modes of thinking are culturally valued.[104]

Stereotype threat and minority status

Stereotype threat is the fear that one's behavior will confirm an existing stereotype of a group with which one identifies or by which one is defined; this fear may in turn lead to an impairment of performance.[105] Testing situations that highlight the fact that intelligence is being measured tend to lower the scores of individuals from racial-ethnic groups who already score lower on average or are expected to score lower. Stereotype threat conditions cause larger than expected IQ differences among groups.[106] Psychometrician Nicholas Mackintosh considers that there is little doubt that the effects of stereotype threat contribute to the IQ gap between black people and white people.[107]

A large number of studies have shown that systemically disadvantaged minorities, such as the African American minority of the United States, generally perform worse in the educational system and in intelligence tests than the majority groups or less disadvantaged minorities such as immigrant or "voluntary" minorities.[40] The explanation of these findings may be that children of caste-like minorities, due to the systemic limitations of their prospects of social advancement, do not have "effort optimism", i.e. they do not have the confidence that acquiring the skills valued by majority society, such as those skills measured by IQ tests, is worthwhile. They may even deliberately reject certain behaviors that are seen as "acting white."[40][108][109]

Research published in 1997 indicates that part of the black-white gap in cognitive ability test scores is due to racial differences in test motivation.[110]

However, attempts to replicate studies evincing significant effects of stereotype threat have not yielded the same results. In 2004 Sackett et al. found that eliminating stereotype threat does not eliminate the racial test performance gap, and in 2005 Tyson et al. found that African Americans have motivation similar to or even better than that of white Americans.[111][112] Self-affirmation exercises promoted by research scientists such as Geoffrey L. Cohen have not been shown to be effective by attempts to replicate his studies.[113] A 2015 meta-analysis conducted by Flore & Wicherts of studies on the relationship between gender and stereotype threat found the observed estimates to be inflated by publication bias, arguing the true effect to be most likely near zero.[114]

Research into the possible genetic influences on test score differences

According to James A. Banks, the argument that group differences are based on genetics is considered "untenable".[39] Currently there is no evidence that the test score gap has a genetic component.[115][51][116] Growing evidence indicates that environmental factors, not genetic ones, are more important in explaining the racial IQ gap.[117] Several lines of investigation have been followed in the attempt to ascertain whether there is a genetic component to the test score gap as well as its relative contribution to the magnitude of the gap.[citation needed]

Genetics of race and intelligence

Geneticist Alan R. Templeton argues that the question about the possible genetic effects on the test score gap is muddled by the general focus on "race" rather than on populations defined by gene frequency or by geographical proximity, and by the general insistence on phrasing the question in terms of heritability.[118] Templeton points out that racial groups neither represent sub-species nor distinct evolutionary lineages, and that therefore there is no basis for making claims about the general intelligence of races.[118] From this point of view the search for possible genetic influences on the black-white test score gap is a priori flawed, because there is no genetic material shared by all Africans or by all Europeans. Mackintosh (2011), however, argues that by using genetic cluster analysis to correlate gene frequencies with continental populations it might be possible to show that African populations have a higher frequency of certain genetic variants that contribute to an average lower intelligence. Such a hypothetical situation could hold without all Africans carrying the same genes or belonging to a single evolutionary lineage. According to Mackintosh, a biological basis for the gap thus cannot be ruled out on a priori grounds.

Intelligence is a polygenic trait. This means that intelligence is under the influence of several genes, possibly several thousand. The effect of most individual genetic variants on intelligence is thought to be very small, well below 1% of the variance in g. Current studies using quantitative trait loci have yielded little success in the search for genes influencing intelligence. Robert Plomin is confident that QTLs responsible for the variation in IQ scores exist, but due to their small effect sizes, more powerful tools of analysis will be required to detect them.[119] Others assert that no useful answers can be reasonably expected from such research before an understanding of the relation between DNA and human phenotypes emerges.[66] Several candidate genes have been proposed to have a relationship with intelligence.[120][121] However, a review of candidate genes for intelligence published in Deary, Johnson & Houlihan (2009) failed to find evidence of an association between these genes and general intelligence, stating "there is still almost no replicated evidence concerning the individual genes, which have variants that contribute to intelligence differences".[122] In 2001, a review in the Journal of Black Psychology refuted eight major premises on which the hereditarian view regarding race and intelligence is based.[123]

A 2005 literature review article by Sternberg, Grigorenko and Kidd stated that no gene has been shown to be linked to intelligence, "so attempts to provide a compelling genetic link of race to intelligence are not feasible at this time".[124] Hunt (2010, p. 447) and Mackintosh (2011, p. 344) concurred, both scholars noting that while several environmental factors have been shown to influence the IQ gap, the evidence for a genetic influence has been circumstantial, and according to Mackintosh negligible. Mackintosh however suggests that it may never become possible to account satisfyingly for the relative contributions of genetic and environmental factors. The 2012 review by Nisbett et al. (2012a) concluded that "Almost no genetic polymorphisms have been discovered that are consistently associated with variation in IQ in the normal range". Hunt and several other researchers however maintain that genetic causes cannot be ruled out, and that new evidence may yet show a genetic contribution to the gap. Hunt concurs with Rushton and Jensen who considered the 100% environmental hypothesis to be impossible. Nonetheless, Nisbett and colleagues (2012) consider the entire IQ gap to be explained by the environmental factors that have thus far been demonstrated to influence it, and Mackintosh does not find this view to be unreasonable.[51]

Heritability within and between groups

Twin studies of intelligence have reported high heritability values. However, these studies are based on questionable assumptions.[125] When used in the context of human behavior genetics, the term "heritability" is highly misleading, as it does not convey any information about the relative importance of genetic or environmental factors on the development of a given trait, nor does it convey the extent to which that trait is genetically determined.[126] Arguments in support of a genetic explanation of racial differences in IQ are sometimes fallacious. For instance, hereditarians have sometimes cited the failure of known environmental factors to account for such differences, or the high heritability of intelligence within races, as evidence that racial differences in IQ are genetic.[127]

Psychometricians have found that intelligence is substantially heritable within populations, with 30–50% of variance in IQ scores in early childhood being attributable to genetic factors in analyzed US populations, increasing to 75–80% by late adolescence.[40][122] In biology heritability is defined as the ratio of variation attributable to genetic differences in an observable trait to the trait's total observable variation. The heritability of a trait describes the proportion of variation in the trait that is attributable to genetic factors within a particular population. A heritability of 1 indicates that variation correlates fully with genetic variation and a heritability of 0 indicates that there is no correlation between the trait and genes at all. In psychological testing, heritability tends to be understood as the degree of correlation between the results of a test taker and those of their biological parents. However, since high heritability is simply a correlation between traits and genes, it does not describe the causes of heritability which in humans can be either genetic or environmental.

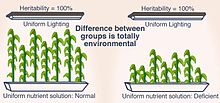

Therefore, a high heritability measure does not imply that a trait is genetic or unchangeable, however, as environmental factors that affect all group members equally will not be measured by heritability and the heritability of a trait may also change over time in response to changes in the distribution of genes and environmental factors.[40] High heritability also doesn't imply that all of the heritability is genetically determined, but can also be due to environmental differences that affect only a certain genetically defined group (indirect heritability).[128] The figure to the left demonstrates how heritability works. In both gardens the difference between tall and short cornstalks is 100% heritable as cornstalks that are genetically disposed for growing tall will become taller than those without this disposition, but the difference in height between the cornstalks to the left and those on the right is 100% environmental as it is due to different nutrients being supplied to the two gardens. Hence the causes of differences within a group and between groups may not be the same, even when looking at traits that are highly heritable.[128] In his criticism of the Bell Curve, Noam Chomsky further illustrated this with the example of women wearing earrings:

To borrow an example from Ned Block, "some years ago when only women wore earrings, the heritability of having an earring was high because differences in whether a person had an earring was due to a chromosomal difference, XX vs. XY." No one has yet suggested that wearing earrings, or ties, is "in our genes," an inescapable fate that environment cannot influence, "dooming the liberal notion."[129]

In regards to the IQ gap the question becomes whether racial groups can be shown to be influenced by different environmental factors that may account for the observed differences between them. Jensen originally argued that given the high heritability of IQ the only way that the IQ gap could be explained as caused by the environment would be if it could be shown that all black people were subject to a single "x-factor" which affected no white populations while affecting all black populations equally.[130] Jensen considered the existence of such an x-factor to be extremely improbable, but Flynn's discovery of the Flynn effect showed that in spite of high heritability environmental factors could cause considerable disparities in IQ between generations of the same population, showing that the existence of such an x-factor was not only possible but real.[131]

Jensen has also argued that heritability of traits rises with age as the genetic potential of individuals becomes expressed. He sees this as related to the fact that the IQ gap between white and black test takers has been shown to appear gradually, with the gap widening as cohorts reach adulthood. This he sees as a further argument in favor of Spearman's hypothesis (see section below).[citation needed]

In contrast, Dickens and Flynn argued that the conventional interpretation ignores the role of feedback between factors, such as those with a small initial IQ advantage, genetic or environmental, seeking out more stimulating environments which will gradually greatly increase their advantage, which, as one consequence in their alternative model, would mean that the "heritability" figure is only in part due to direct effects of genotype on IQ.[132][133][134]

Today researchers such as Hunt (2010), Nisbett et al. (2012a) and Mackintosh (2011) consider that rather than a single factor accounting for the entire gap, probably many different environmental factors differ systematically between the environments of white and black people converge to create part of the gap and perhaps all of it. They argue that it does not make sense to talk about a single universal heritability figure for IQ, rather, they state, heritability of IQ varies between and within groups. They point specifically to studies showing a higher heritability of test scores in white and medium-high SES families, but considerably lower heritability for black and low-SES families. This they interpret to mean that children who grow up with limited resources do not get to develop their full genetic potential.[51]

Multiple studies have been conducted over the past several decades to survey scientific estimates on the heritability of the IQ gap. A review by Snydermann and Rothman in 1988 found that 45% of the scientists they questioned believed the gap to be "a product of genetic and environmental variation," 15% and 1% respectively "entirely to environmental" and "genetic variation," while the remaining 38% either declined to answer or stated that the evidence was inconclusive.[135] The heritability of intelligence was estimated on average to be 59.6% for white Americans and 57.0% for black Americans among those who answered that the evidence was sufficiently conclusive.[136][broken footnote] The Wall Street Journal published an editorial by Linda Gottfredson in 1994, signed by 52 professors specializing in intelligence and allied fields, that estimated the heritability of individual variation to range between 40–80%, but also stating that "there is no definitive answer" to explain the racial gap.[137] Social psychologist Donald T. Campbell criticized the report, arguing that it overstated the plausibility of genetic explanations and underestimated the extent of environmental differences between races.[138] A 1995 report by the APA stated that there is more plausible evidence for an environmental than for a genetic explanation, but that there was "no adequate explanation" for the black-white IQ gap.[40] In a 2013 followup on Snyderman & Rothman, Rindermann et al. found the average and median estimates of the black-white IQ gap to be heritable by 47% and 50% respectively among surveyed scientists who believed that the available evidence allowed for a reasonable estimate. This survey however yielded a response rate of 18% (228 participants) compared to Snyderman & Rothman's 65% (661 participants).[139]

Spearman's hypothesis

Spearman's hypothesis states that the magnitude of the black-white difference in tests of cognitive ability is entirely or mainly a function of the extent to which a test measures general mental ability, or g. The hypothesis was first formalized by Arthur Jensen who devised the statistical Method of Correlated Vectors to test it. Jensen holds that if Spearman's hypothesis holds true then some cognitive tasks have a higher g-load than others, and that these tasks are exactly the tasks in which the gap between black and white test takers are greatest. Jensen, and other psychometricians such as Rushton and Lynn, take this to show that the cause of g and the cause of the gap are the same—in their view genetic differences.[140]

Mackintosh (2011, pp. 338–39) acknowledges that Jensen and Rushton have shown a modest correlation between g-loading, heritability, and the test score gap, but did not accept that this demonstrates a genetic origin of the gap. Mackintosh points out that it is the results of exactly those tests that Rushton and Jensen consider to have the highest g-loading and heritability, such as the Wechsler test, that have seen the highest increases due to the Flynn effect. This likely suggests that they are also the most sensitive to environmental changes, which undermines Jensen's argument that the black-white gap is most likely caused by genetic factors. Mackintosh also argues that Spearman's hypothesis, which he considers to be likely to be correct, simply shows that the test score gap is based on whatever cognitive faculty is central to intelligence, but not what this factor is. Nisbett et al. (2012a, p. 146) make the same point, noting also that the increase in the IQ scores of black test takers is necessarily also an increase in g.

James Flynn (2012, pp. 140–1) argues that there is an inherent flaw in Jensen's argument that the correlation between g-loadings, test scores and heritability support a genetic cause of the gap. He points out that as the difficulty of a task increases a low performing group will naturally fall further behind, and heritability will therefore also naturally increase. The same holds for increases in performance which will first affect the least difficult tasks, but only gradually affect the most difficult ones. Flynn thus sees the correlation between in g-loading and the test score gap to offer no clue to the cause of the gap.[141]

Hunt (2010, p. 415) states that many of conclusions of Jensen, and his colleagues rest on the validity of Spearman's hypothesis, and the method of correlated vectors used to test it. Hunt points out that other researchers have found this method of calculation to produce false positive results, and that other statistical methods should be used instead. According to Hunt, Jensen and Rushton's frequent claim that Spearman's hypothesis should be regarded as empirical fact does not hold, and that new studies based on better statistical methods would be required to confirm or reject the hypothesis that the correlation between g-loading, heritability and the IQ gap is due to IQ gaps consisting mostly of g.[citation needed]

Adoption studies

A number of studies have been done on the effect of similar rearing conditions on children from different races. The hypothesis is that by investigating whether black children adopted into white families demonstrated gains in IQ test scores relative to black children reared in black families. Depending on whether their test scores are more similar to their biological or adoptive families, that could be interpreted as either supporting a genetic or an environmental hypothesis. The main point of critique in studies like these however is whether the environment of black children—even when raised in white families—is truly comparable to the environment of white children. Several reviews of the adoption study literature has pointed out that it is perhaps impossible to avoid confounding of biological and environmental factors in this type of studies.[142] Given the differing heritability estimates in medium-high SES and low-SES families, Nisbett et al. (2012a, pp. 134) argue that adoption studies on the whole tend to overstate the role of genetics because they represent a restricted set of environments, mostly in the medium-high SES range.

The Minnesota Transracial Adoption Study (1976) examined the IQ test scores of 122 adopted children and 143 nonadopted children reared by advantaged white families. The children were restudied ten years later.[143][144][145] The study found higher IQ for white people compared to black people, both at age 7 and age 17.[143] Acknowledging the existence of confounding factors, Scarr and Weinberg, the authors of the original study, did not themselves consider that it provided support for either the hereditarian or environmentalist view.[146]

Three other adoption studies found contrary evidence to the Minnesota study, lending support to a mostly environmental hypothesis:

- Eyferth (1961) studied the out-of-wedlock children of black and white soldiers stationed in Germany after World War 2 and then raised by white German mothers in what has become known as the Eyferth study. He found no significant differences in average IQ between groups.

- Tizard et al. (1972) studied black (West Indian), white, and mixed-race children raised in British long-stay residential nurseries. Two out of three tests found no significant differences. One test found higher scores for non-white people.

- Moore (1986) compared black and mixed-race children adopted by either black or white middle-class families in the United States. Moore observed that 23 black and interracial children raised by white parents had a significantly higher mean score than 23 age-matched children raised by black parents (117 vs 104), and argued that differences in early socialization explained these differences.

Frydman and Lynn (1989) showed a mean IQ of 119 for Korean infants adopted by Belgian families. After correcting for the Flynn effect, the IQ of the adopted Korean children was still 10 points higher than the indigenous Belgian children.[147][140][148]

Reviewing the evidence from adoption studies, Mackintosh considers the studies by Tizard and Eyferth to be inconclusive, and the Minnesota study to be consistent only with a partial genetic hypothesis. On the whole, he finds that environmental and genetic variables remain confounded and considers evidence from adoption studies inconclusive, and fully compatible with a 100% environmental explanation.[142] Similarly, Drew Thomas argues that race differences in IQ that appear in adoption studies are in fact an artifact of methodology and that East Asian IQ advantages and Black IQ disadvantages disappear when this is controlled for.[149]

Racial admixture studies

Most people have an ancestry from different geographic regions, particularly African Americans typically have ancestors from both Africa and Europe, with, on average, 20% of their genome inherited from European ancestors.[150] If racial IQ gaps have a partially genetic basis, one might expect black people with a higher degree of European ancestry to score higher on IQ tests than black people with less European ancestry, because the genes inherited from European ancestors would likely include some genes with a positive effect on IQ.[151] Geneticist Alan Templeton has argued that an experiment based on the Mendelian "common garden" design where specimens with different hybrid compositions are subjected to the same environmental influences, would be the only way to definitively show a causal relation between genes and IQ. Summarizing the findings of admixture studies, he concludes that it has shown no significant correlation between any cognitive and the degree of African or European ancestry.[152]

Studies have employed different ways of measuring or approximating relative degrees of ancestry from Africa and Europe. One set of studies have used skin color as a measure, and other studies have used blood groups. Loehlin (2000) surveys the literature and argues that the blood groups studies may be seen as providing some support to the genetic hypothesis, even though the correlation between ancestry and IQ was quite low. He finds that studies by Eyferth (1961), Willerman, Naylor & Myrianthopoulos (1970) did not find a correlation between degree of African/European ancestry and IQ. The latter study did find a difference based on the race of the mother, with children of white mothers with black fathers scoring higher than children of black mothers and white fathers. Loehlin considers that such a finding is compatible with either a genetic or an environmental cause. All in all Loehlin finds admixture studies inconclusive and recommends more research.

Reviewing the evidence from admixture studies Hunt (2010) considers it to be inconclusive because of too many uncontrolled variables. Mackintosh (2011, p. 338) quotes a statement by Nisbett (2009) to the effect that admixture studies have not provided a shred of evidence in favor of a genetic basis for the gap.

Mental chronometry

Mental chronometry measures the elapsed time between the presentation of a sensory stimulus and the subsequent behavioral response by the participant. This reaction time (RT) is considered a measure of the speed and efficiency with which the brain processes information.[153] Scores on most types of RT tasks tend to correlate with scores on standard IQ tests as well as with g, and no relationship has been found between RT and any other psychometric factors independent of g.[153] The strength of the correlation with IQ varies from one RT test to another, but Hans Eysenck gives 0.40 as a typical correlation under favorable conditions.[154] According to Jensen individual differences in RT have a substantial genetic component, and heritability is higher for performance on tests that correlate more strongly with IQ.[155] Nisbett argues that some studies have found correlations closer to 0.2, and that the correlation is not always found.[156]

Several studies have found differences between races in average reaction times. These studies have generally found that reaction times among black, Asian and white children follow the same pattern as IQ scores.[157][158][159] Black-white differences in reaction time, however, tend to be small (average effect size .18).[160] Rushton & Jensen (2005) have argued that reaction time is independent of culture and that the existence of race differences in average reaction time is evidence that the cause of racial IQ gaps is partially genetic instead of entirely cultural. Responding to this argument in Intelligence and How to Get It, Nisbett has pointed to the Jensen & Whang (1993) study in which a group of Chinese Americans had longer reaction times than a group of European Americans, despite having higher IQs. Nisbett also mentions findings in Flynn (1991) and Deary (2001) suggesting that movement time (the measure of how long it takes a person to move a finger after making the decision to do so) correlates with IQ just as strongly as reaction time, and that average movement time is faster for black people than for white people.[161] Mackintosh (2011, p. 339) considers reaction time evidence unconvincing and points out that other cognitive tests that also correlate well with IQ show no disparity at all, for example the habituation/dishabituation test. And he points out that studies show that rhesus monkeys have shorter reaction times than American college students, suggesting that different reaction times may not tell us anything useful about intelligence.

Brain size

A number of studies have reported a moderate statistical correlation between differences in IQ and brain size between individuals in the same group.[162][163] Some scholars have reported differences in average brain sizes between racial groups,[164] although this is unlikely to be a good measure of IQ as brain size also differs between men and women, but without significant differences in IQ. At the same time newborn black children have the same average brain size as white children, suggesting that the difference in average size could be accounted for by differences in environment. Several factors that reduce brain size have been demonstrated to disproportionately affect black children.[51]

Earl Hunt states that brain size is found to have a correlation of about .35 with intelligence among white people and cites studies showing that genes may account for as much as 90% of individual variation in brain size. According to Hunt, race differences in average brain size could potentially be an important argument for a possible genetic contribution to racial IQ gaps. Nonetheless, Hunt notes that Rushton's head size data would account for a difference of .09 standard deviations between black and white average test scores, less than a tenth of the 1.0 standard deviation gap in average scores that is observed.[132][165] Wicherts, Borsboom, & Dolan (2010) argue that black-white differences in brain size are insufficient to explain 91% to 95% of the black-white IQ gap.[166]

Archaeological data

Archaeological evidence does not support claims by Rushton and others that black people' cognitive ability was inferior to white people' during prehistoric times as a result of evolution.[167]

Policy relevance and ethics

The 1996 report of the APA commented on the ethics of research on race and intelligence.[33] Gray & Thompson (2004) as well as Hunt & Carlson (2007) have also discussed different possible ethical guidelines.[33][168][non-primary source needed] Nature in 2009 featured two editorials on the ethics of research in race and intelligence by Steven Rose (against) and Stephen J. Ceci and Wendy M. Williams (for).[169][170]

According to critics, research on group differences in IQ will reproduce the negative effects of social ideologies (such as Nazism or social Darwinism) that were justified in part on claimed hereditary racial differences.[31][171] Steven Rose maintains that the history of eugenics makes this field of research difficult to reconcile with current ethical standards for science.[170]

Linda Gottfredson argues that suggestion of higher ethical standards for research into group differences in intelligence is a double standard applied in order to undermine disliked results.[172] James R. Flynn has argued that had there been a ban on research on possibly poorly conceived ideas, much valuable research on intelligence testing (including his own discovery of the Flynn effect) would not have occurred.[173]

Jensen and Rushton argued that the existence of biological group differences does not rule out, but raises questions about the worthiness of policies such as affirmative action or placing a premium on diversity. They also argued for the importance of teaching people not to overgeneralize or stereotype individuals based on average group differences, because of the significant overlap of people with varying intelligence between different races.[174]

Some who hold the environmentalist viewpoint argue for increased interventions in order to close the gaps.[175] Nisbett argues that schools can be greatly improved and that many interventions at every age level are possible.[176] Flynn, arguing for the importance of the black subculture, writes that "America will have to address all the aspects of black experience that are disadvantageous, beginning with the regeneration of inner city neighbourhoods and their schools. A resident police office and teacher in every apartment block would be a good start."[177] Researchers from both sides agree that interventions should be better researched.[156][178]

Especially in developing nations, society has been urged to take on the prevention of cognitive impairment in children as of the highest priority. Possible preventable causes include malnutrition, infectious diseases such as meningitis, parasites, cerebral malaria, in utero drug and alcohol exposure, newborn asphyxia, low birth weight, head injuries, lead poisoning and endocrine disorders.[179]

See also

- Behavioral epigenetics

- Model minority

- Outline of human intelligence

- Race and crime in the United States

References

Notes

- ^ Jackson & Weidman 2004, p. 23.

- ^ Plotnik & Kouyoumdjian 2011.

- ^ Jackson & Weidman 2004, p. 116.

- ^ Jackson & Weidman 2004, p. 116, 309.

- ^ Pickren & Rutherford 2010, p. 163.

- ^ Spiro 2009.

- ^ Ludy 2006

- ^ Jackson & Weidman 2004, pp. 130–32.

- ^ a b c Tucker 2002.

- ^ Jackson 2005.

- ^ Shurkin 2006.

- ^ Panofsky, Aaron (2014). Misbehaving Science. Controversy and the Development of Behavior Genetics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-05831-3.

- ^ Alland 2002, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Herrnstein & Murray 1994.

- ^ Mackintosh 1998

- ^ a b c Maltby, Day & Macaskill 2007

- ^ Graves 2002a.

- ^ Graves 2002b.

- ^ Grossman & Kaufman 2001

- ^ Berlet 2003.

- ^ Pioneer Fund Board Archived 2011-05-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Falk 2008, p. 18

- ^ Wroe 2008, p. 81

- ^ a b Schacter, Gilbert & Wegner 2007, pp. 350–1

- ^ a b Sternberg, Grigorenko & Kidd 2005

- ^ Mackintosh 2011, p. 359.

- ^ Daley & Onwuegbuzie 2011, p. 294.

- ^ Smay & Armelagos 2000.

- ^ Rotimi, Charles N. (2004). "Are medical and nonmedical uses of large-scale genomic markers conflating genetics and 'race'?". Nature Genetics. 36 (11 Suppl): 43–47. doi:10.1038/ng1439. PMID 15508002.

Two facts are relevant: (i) as a result of different evolutionary forces, including natural selection, there are geographical patterns of genetic variations that correspond, for the most part, to continental origin; and (ii) observed patterns of geographical differences in genetic information do not correspond to our notion of social identities, including 'race' and 'ethnicity

- ^ Schaefer 2008

- ^ a b AAA 1998

- ^ Rowe 2005

- ^ a b c d Hunt & Carlson 2007

- ^ Sternberg & Grigorenko 2007

- ^ Brace 2005

- ^ Graves 2001

- ^ Hunt 2010, pp. 408–10

- ^ Hampshire et al. 2012.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of Diversity in Education. SAGE. 2012. p. 1209. ISBN 9781412981521.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Neisser et al. 1996.

- ^ a b Roth et al. 2001

- ^ Niu & Brass 2011

- ^ Mackintosh 1998, p. 162

- ^ Swain, Carol (2003). Contemporary voices of white nationalism in America. Cambridge, UK New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0521016933. Note: this quote is from the authors' introductory essay, not from the interviews.

- ^ te Nijenhuis, Jan; van der Flier, Henk (2013). "Is the Flynn effect on g?: A meta-analysis". Intelligence. 41 (6): 802–807. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2013.03.001.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Vincent 1991.

- ^ Dickens & Flynn 2006.

- ^ Neisser, Ulric (Ed). 1998. The rising curve: Long-term gains in IQ and related measures. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association

- ^ Murray 2006.

- ^ Murray 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Nisbett et al. 2012a.

- ^ Nisbett et al. 2012b.

- ^ Rindermann & Thompson 2013.

- ^ Rindermann, Heiner; Pinchelmann, Stefan (13 October 2015). "Future Cognitive Ability: US IQ Prediction until 2060 Based on NAEP". PLOS ONE. 10 (10): e0138412. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1038412R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138412. PMC 4603674. PMID 26460731.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Bellinger, Stiles & Needleman 1992

- ^ MMWR 2005

- ^ a b Campbell et al. 2002

- ^ Ivanovic et al. 2004

- ^ Saloojee & Pettifor 2001

- ^ Agency For Toxic Substances And Disease Registry Case Studies In Environmental Medicine (CSEM) (2012-02-15). "Principles of Pediatric Environmental Health, The Child as Susceptible Host: A Developmental Approach to Pediatric Environmental Medicine" (PDF). U.S. Department for Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

- ^ Lanphear, Bruce P.; Hornung, Richard; Khoury, Jane; Yolton, Kimberly; Baghurst, Peter; Bellinger, David C.; Canfield, Richard L.; Dietrich, Kim N.; Bornschein, Robert; Greene, Tom; Rothenberg, Stephen J.; Needleman, Herbert L.; Schnaas, Lourdes; Wasserman, Gail; Graziano, Joseph; Roberts, Russell (2005-03-18). "Low-Level Environmental Lead Exposure and Children's Intellectual Function: An International Pooled Analysis". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (7): 894–899. doi:10.1289/ehp.7688. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 1257652. PMID 16002379.

- ^ Qian et al. 2005

- ^ Feyrer, James; Politi, Dimitra; Weil, David N. (2017). "The Cognitive Effects of Micronutrient Deficiency: Evidence from Salt Iodization in the United States" (PDF). Journal of the European Economic Association. 15 (2): 355–387. doi:10.1093/jeea/jvw002.

- ^ The Lancet Series on Maternal and Child Undernutrition, 2008.

- ^ Nisbett 2009, p. 101

- ^ a b Cooper 2005

- ^ Mackintosh 2011, pp. 343–44.

- ^ Behrman, Alderman & Hoddinott 2004

- ^ Colom, R.; Lluis-Font, J. M.; Andrés-Pueyo, A. (2005). "The generational intelligence gains are caused by decreasing variance in the lower half of the distribution: supporting evidence for the nutrition hypothesis". Intelligence. 33: 83–91. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2004.07.010.

- ^ Flynn, J. R. (2009). "Requiem for nutrition as the cause of IQ gains: Raven's gains in Britain 1938 to 2008". Economics and Human Biology. 7 (1): 18–27. doi:10.1016/j.ehb.2009.01.009. PMID 19251490.

- ^ Eppig, Fincher & Thornhill 2010

- ^ Eppig 2011

- ^ "Long-term effects of breastfeeding – a systemic review" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Cynthia G. Colen and David M. Ramey (2014). "Is Breast Truly Best? Estimating the Effect of Breastfeeding on Long-term Child Wellbeing in the United States Using Sibling Comparisons". Social Science & Medicine. 109 (1): 55–65. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.027. PMC 4077166. PMID 24698713.

- ^ Reichman 2005

- ^ Manly et al. 2002 and Manly et al. 2004

- ^ Mickelson 2003

- ^ Elhoweris et al. 2005

- ^ Miele 2002, p. 133

- ^ Fagan, Joseph F; Holland, Cynthia R (2002). "Equal opportunity and racial differences in IQ". Intelligence. 30 (4): 361–387. doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(02)00080-6.

- ^ Fagan, J.F.; Holland, C.R. (2007). "Racial equality in intelligence: Predictions from a theory of intelligence as processing". Intelligence. 35 (4): 319–334. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2006.08.009.

- ^ Daley & Onwuegbuzie 2011.

- ^ Marks, D.F. (2010). "IQ variations across time, race, and nationality: An artifact of differences in literacy skills". Psychological Reports. 106 (3): 643–664. doi:10.2466/pr0.106.3.643-664. PMID 20712152.

- ^ Barry, Scott (2010-08-23). "The Flynn Effect and IQ Disparities Among Races, Ethnicities, and Nations: Are There Common Links?". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2014-08-22.

- ^ McKay, Patrick F.; Doverspike, Dennis; Bowen‐Hilton, Doreen; McKay, Quintonia D. (2003). "The Effects of Demographic Variables and Stereotype Threat on Black/White Differences in Cognitive Ability Test Performance". Journal of Business and Psychology. 18 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1023/A:1025062703113.

- ^ Hunt 2010, p. 428.

- ^ Magnuson, Katherine A.; Duncan, Greg J. (December 2006). "The role of family socioeconomic resources in the black–white test score gap among young children". Developmental Review. 26 (4): 365–399. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2006.06.004.

- ^ Hart, Betty; Risley, Todd (1995). Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children. Brookes Publishing, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

- ^ Scarr-Salapatek, S. (1971). "Race, social class, and IQ". Science. 174 (4016): 1285–95. Bibcode:1971Sci...174.1285S. doi:10.1126/science.174.4016.1285. PMID 5167501.

- ^ Scarr-Salapatek, S. (1974). "Some myths about heritability and IQ". Nature. 251 (5475): 463–464. Bibcode:1974Natur.251..463S. doi:10.1038/251463b0.

- ^ D. C. Rowe. (1994). The Limits of Family Influence: Genes, Experience and Behaviour. Guilford Press. London

- ^ Kirkpatrick, R. M.; McGue, M.; Iacono, W. G. (2015). "Replication of a gene-environment interaction Via Multimodel inference: additive-genetic variance in adolescents' general cognitive ability increases with family-of-origin socioeconomic status". Behav Genet. 45 (2): 200–14. doi:10.1007/s10519-014-9698-y. PMC 4374354. PMID 25539975.

- ^ Bronfenbrenner, Urie; Ceci, Stephen J. (October 1994). "Nature-nuture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model". Psychological Review. 101 (4): 568–586. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.568. PMID 7984707.

- ^ Cottrell, Newman & Roisman 2015.

- ^ Cronshaw et al. 2006, p. 278

- ^ Verney et al. 2005

- ^ Borsboom 2006

- ^ Shuttleworth-Edwards et al. 2004

- ^ Richardson 2004