Hermetica: Difference between revisions

Ian.thomson (talk | contribs) →Translations: Bude is the standard and Copenhaver's is based on that -- it's why Cambridge UP uses that edition. Latham's translation uses garbage grammar for the sake of being pretentiously unreadable and comes from a quite unacademic publisher targetting fluffbunnies. It also needs an independent source (not just an Amazon listing). Personally, I find Clement Salaman et al's Way of Hermes the most readable but there's no reviews for that one. |

→Translations: Ian Thompson is not a qualified Latin translation and doesn't even speak English "garbage" is not an English word, nor is "fluffbunny". Latham is a qualified Latin translator, his specialism is in Classical Latin and Roman archaeology. His edition is replete with scholarly references, almost exclusively primary sources from the classical world. Ian - I would like to see *you* translate even a single sentence in Latin, let alone several hundred pages. |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

==Translations== |

==Translations== |

||

[[John Everard (preacher)|John Everard]]'s historically important 1650 translation into [[English language|English]] of the ''Corpus Hermeticum'', entitled ''The Divine Pymander in XVII books'' (London, 1650) was from Ficino's Latin translation; it is no longer considered reliable by scholars.{{Citation needed|date=April 2020}} The modern standard editions are the Budé edition by A. D. Nock and A.-J. Festugière (Greek and French, 1946, repr. 1991) and Brian P. Copenhaver (English, 1992).<ref>{{cite journal|title=A New Translation of the Hermetica - Brian P. Copenhaver: Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. |author=J. Gwyn Griffiths |periodical=The Classical Review |volume=43 |issue=2 |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |date=October 1993 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/classical-review/article/new-translation-of-the-hermetica-copenhaver-brian-p-hermetica-the-greek-corpus-hermeticum-and-the-latin-asclepius-in-a-new-english-translation-with-notes-and-introduction-pp-lxxxiii-320-cambridge-cambridge-university-press-1992-45/A53F30836C4E16E6CDD270D135FC83C1 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Brian P. Copenhaver, Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asdepius in a New English Translation with Notes and Introduction. |author=John Monfasani |periodical=The British Journal for the History of Science |volume=26 |issue=4 |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |date=December 1993 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-for-the-history-of-science/article/brian-p-copenhaver-hermetica-the-greek-corpus-hermeticum-and-the-latin-asdepius-in-a-new-english-translation-with-notes-and-introduction-cambridge-cambridge-university-press-1992-pp-lxxxiii-320-isbn-0521361443-4500-6995/7F8F960A233E2E4D1D3526BE2D9EC6C1}}</ref> |

[[John Everard (preacher)|John Everard]]'s historically important 1650 translation into [[English language|English]] of the ''Corpus Hermeticum'', entitled ''The Divine Pymander in XVII books'' (London, 1650) was from Ficino's Latin translation; it is no longer considered reliable by scholars.{{Citation needed|date=April 2020}} The modern standard editions are the Budé edition by A. D. Nock and A.-J. Festugière (Greek and French, 1946, repr. 1991) and Brian P. Copenhaver (English, 1992).<ref>{{cite journal|title=A New Translation of the Hermetica - Brian P. Copenhaver: Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. |author=J. Gwyn Griffiths |periodical=The Classical Review |volume=43 |issue=2 |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |date=October 1993 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/classical-review/article/new-translation-of-the-hermetica-copenhaver-brian-p-hermetica-the-greek-corpus-hermeticum-and-the-latin-asclepius-in-a-new-english-translation-with-notes-and-introduction-pp-lxxxiii-320-cambridge-cambridge-university-press-1992-45/A53F30836C4E16E6CDD270D135FC83C1 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Brian P. Copenhaver, Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asdepius in a New English Translation with Notes and Introduction. |author=John Monfasani |periodical=The British Journal for the History of Science |volume=26 |issue=4 |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |date=December 1993 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-for-the-history-of-science/article/brian-p-copenhaver-hermetica-the-greek-corpus-hermeticum-and-the-latin-asdepius-in-a-new-english-translation-with-notes-and-introduction-cambridge-cambridge-university-press-1992-pp-lxxxiii-320-isbn-0521361443-4500-6995/7F8F960A233E2E4D1D3526BE2D9EC6C1}}</ref> The most recent translation was done in 2020 by Maxwell Lewis Latham. |

||

==Contents of ''Corpus Hermeticum''== |

==Contents of ''Corpus Hermeticum''== |

||

Revision as of 15:06, 21 June 2020

The Hermetica are Egyptian-Greek wisdom texts from the 2nd century or earlier,[1][2][3][4] which are mostly presented as dialogues in which a teacher, generally identified as Hermes Trismegistus ("thrice-greatest Hermes"), enlightens a disciple. The texts form the basis of Hermeticism. They discuss the divine, the cosmos, mind, and nature. Some touch upon alchemy, astrology, and related concepts.

Scope

| Part of a series on |

| Hermeticism |

|---|

|

The term particularly applies to the Corpus Hermeticum, Marsilio Ficino's Latin translation in fourteen tracts, of which eight early printed editions appeared before 1500 and a further twenty-two by 1641.[5] This collection, which includes Poimandres and some addresses of Hermes to disciples Tat, Ammon and Asclepius, was said to have originated in the school of Ammonius Saccas and to have passed through the keeping of Michael Psellus: it is preserved in fourteenth century manuscripts.[6] The last three tracts in modern editions were translated independently from another manuscript by Ficino's contemporary Lodovico Lazzarelli (1447–1500) and first printed in 1507. Extensive quotes of similar material are found in classical authors such as Joannes Stobaeus.

Parts of the Hermetica appeared in the 2nd-century Gnostic library found in Nag Hammadi. Other works in Syriac, Arabic, Coptic and other languages may also be termed Hermetica — another famous tract is the Emerald Tablet, which teaches the doctrine "as above, so below".

For a long time, it was thought that these texts were remnants of an extensive literature, part of the syncretic cultural movement that also included the Neoplatonists of the Greco-Roman mysteries and late Orphic and Pythagorean literature and influenced Gnostic forms of the Abrahamic religions. However, there are significant differences:[7] the Hermetica are little concerned with Greek mythology or the technical minutiae of metaphysical Neoplatonism. In addition, Neoplatonic philosophers, who quote works of Orpheus, Zoroaster and Pythagoras, cite Hermes Trismegistus less often. Still, most of these schools do agree in attributing the creation of the world to a Demiurge rather than the supreme being[8] and in accepting reincarnation.

Many Christian intellectuals from all eras have written about Hermeticism, both positive and negative.[9][10] However, modern scholars find no traces of Christian influences in the texts.[11] Although Christian authors have looked for similarities between Hermeticism and Christian scriptures, scholars remain unconvinced.[12]

Character and antiquity

The extant Egyptian-Greek texts dwell upon the oneness and goodness of God, urge purification of the soul, and defend pagan religious practices, such as the veneration of images. Their concerns are practical in nature, their end is a spiritual rebirth through the enlightenment of the mind:

Seeing within myself an immaterial vision that came from the mercy of God, I went out of myself into an immortal body, and now I am not what I was before. I have been born in mind![13]

While they are difficult to date with precision, the texts of the Corpus were likely redacted between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD. During the Renaissance these texts were believed to be of ancient Egyptian origin and even today some readers, translators and scholars[14] believe them to date from Pharaonic Egypt. Since Plato's Timaeus dwelt upon the great antiquity of the Egyptian teachings upon which the philosopher purported to draw,[15] some scholars are willing to accept that these texts were the sources of some Greek ideas.[16] In that line of thinking, it has also been suggested that there are some parallels between Hermetic dialogues and Hellenic dialogues, particularly Plato.[17][18]

Centuries before the discovery of the Nag Hammadi library, and based on archaic translations, classical scholar Isaac Casaubon (1559–1614) had argued that some texts, mainly those dealing with philosophy, betrayed too recent a vocabulary. Hellenisms in the language itself point to a Greek-era origin. However, flaws in this dating were discerned by the 17th century scholar Ralph Cudworth, who argued that Casaubon's allegation of forgery could only be applied to three of the seventeen treatises contained within the Corpus Hermeticum. Moreover, Cudworth noted Casaubon's failure to acknowledge the codification of these treatises as a late formulation of a pre-existing oral tradition. According to Cudworth, the texts must be viewed as a terminus ad quem and not terminus a quo. Lost Greek texts, and many of the surviving vulgate books, contained discussions of alchemy clothed in philosophical metaphor. And one text, the Asclepius, lost in Greek but partially preserved in Latin, contained a bloody prophecy of the end of Roman rule in Egypt and the resurgence of pagan Egyptian power. Thus, it would be fair to assess the Corpus Hermeticum as intellectually eclectic.[19]

More recent research, while affirming the late dating in a period of syncretic cultural ferment in Roman Egypt, suggests more continuity with the culture of Pharaonic Egypt than had previously been believed.[20] There are many parallels with Egyptian prophecies and hymns to the gods but the closest comparisons can be found in Egyptian wisdom literature, which is characteristically couched in words of advice from a "father" to a "son".[21] Demotic (late Egyptian) papyri contain substantial sections of a dialogue of Hermetic type between Thoth and a disciple.[22] Egyptologist Sir William Flinders Petrie states that some texts in the Hermetic corpus date back to the 6th century BC during the Persian period.[23] Other scholars that also provided arguments and evidence in favor of the Egyptian thesis include Stricker, Doresse, Krause, Francois Daumas, Philippe Derchain, Serge Sauneron, J.D. Ray, B.R. Rees and Jean-Pierre Mahe.[24]

Later history

Many hermetic texts were lost to Western culture during the Middle Ages but rediscovered in Byzantine copies and popularized in Italy during the Renaissance. The impetus for this revival came from the Latin translation by Marsilio Ficino, a member of the de' Medici court, who published a collection of thirteen tractates in 1471, as De potestate et sapientia Dei.[25] The Hermetica provided a seminal impetus in the development of Renaissance thought and culture, having a profound impact on alchemy and modern magic as well as influencing philosophers such as Giordano Bruno and Pico della Mirandola, Ficino's student. This influence continued as late as the 17th century with authors such as Sir Thomas Browne.

Although the most famous examples of Hermetic literature were products of Greek-speakers under Roman rule, the genre did not suddenly stop with the fall of the Empire but continued to be produced in Coptic, Syriac, Arabic, Armenian and Byzantine Greek. The most famous example of this later Hermetica is the Emerald Tablet, known from medieval Latin and Arabic manuscripts with a possible Syriac source. Little else of this rich literature is easily accessible to non-specialists. The mostly gnostic Nag Hammadi Library, discovered in 1945, also contained one previously unknown hermetic text called The Ogdoad and the Ennead, a description of a hermetic initiation into gnosis that has led to new perspectives on the nature of Hermetism as a whole, particularly due to the research of Jean-Pierre Mahé.[26]

Translations

John Everard's historically important 1650 translation into English of the Corpus Hermeticum, entitled The Divine Pymander in XVII books (London, 1650) was from Ficino's Latin translation; it is no longer considered reliable by scholars.[citation needed] The modern standard editions are the Budé edition by A. D. Nock and A.-J. Festugière (Greek and French, 1946, repr. 1991) and Brian P. Copenhaver (English, 1992).[27][28] The most recent translation was done in 2020 by Maxwell Lewis Latham.

Contents of Corpus Hermeticum

The following are the titles given to the eighteen tracts, as translated by G.R.S. Mead:

- I. Pœmandres, the Shepherd of Men

- (II.) The General Sermon

- II. (III.) To Asclepius

- III. (IV.) The Sacred Sermon

- IV. (V.) The Cup or Monad

- V. (VI.) Though Unmanifest God is Most Manifest

- VI. (VII.) In God Alone is Good and Elsewhere Nowhere

- VII. (VIII.) The Greatest Ill Among Men is Ignorance of God

- VIII. (IX.) That No One of Existing Things doth Perish, but Men in Error Speak of Their Changes as Destructions and as Deaths

- IX. (X.) On Thought and Sense

- X. (XI.) The Key

- XI. (XII.) Mind Unto Hermes

- XII. (XIII.) About the Common Mind

- XIII. (XIV.) The Secret Sermon on the Mountain

- XIV. (XV.) A Letter to Asclepius

- (XVI.) The Definitions of Asclepius unto King Ammon

- (XVII.) Of Asclepius to the King

- (XVIII.) The Encomium of Kings

The following are the titles given by John Everard:

- The First Book

- The Second Book. Called Poemander

- The Third Book. Called The Holy Sermon

- The Fourth Book. Called The Key

- The Fifth Book

- The Sixth Book. Called That in God alone is Good

- The Seventh Book. His Secret Sermon in the Mount Of Regeneration, and

- The Profession of Silence. To His Son Tat

- The Eighth Book. That The Greatest Evil In Man, Is The Not Knowing God

- The Ninth Book. A Universal Sermon To Asclepius

- The Tenth Book. The Mind to Hermes

- The Eleventh Book. Of the Common Mind to Tat

- The Twelfth Book. His Crater or Monas

- The Thirteenth Book. Of Sense and Understanding

- The Fourteenth Book. Of Operation and Sense

- The Fifteenth Book. Of Truth to His Son Tat

- The Sixteenth Book. That None of the Things that are, can Perish

- The Seventeenth Book. To Asclepius, to be Truly Wise

See also

References

- ^ Copenhaver, Brian P. (1995). "Introduction". Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521425438.

Scholars generally locate the theoretical Hermetica, 100 to 300 CE; most would put C.H. I toward the beginning of that time. [...] [I]t should be noted that Jean-Pierre Mahe accepts a second-century limit only for the individual texts as they stand, pointing out that the materials on which they are based may come from the first century CE or even earlier. [...] To find theoretical Hermetic writings in Egypt, in Coptic [...] was a stunning challenge to the older view, whose major champion was Father Festugiere, that the Hermetica could be entirely understood in a post-Platonic Greek context.

- ^ Copenhaver, Brian P. (1995). "Introduction". Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521425438.

[...] survivals from the earliest Hermetic literature, some conceivably as early as the fourth century BCE

- ^ Copenhaver, Brian P. (1995). "Introduction". Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521425438.

[...] Hermetic sentences derived from similar elements in ancient Egyptian wisdom literature, especially the genre called "Instructions" that reached back to the Old Kingdom

- ^ Frowde, Henry. Transactions Of The Third International Congress For The History Of Religions Vol 1.

[T]he Kore Kosmou, is dated probably to 510 B.C., and certainly within a century after that, by an allusion to the Persian rule [...] the Definitions of Asclepius [...] as early as 350 B.C.

- ^ Noted by George Sarton, review of Walter Scott's Hermetica, Isis 8.2 (May 1926:343-346) p. 345

- ^ Anon, Hermetica – a new translation, Pembridge Design Studio Press, 1982

- ^ Broek, Roelof Van Den. "Gnosticism and Hermitism in Antiquity: Two Roads to Salvation." In Broek, Roelof Van Den, and Wouter J. Hanegraaff. 1998. Gnosis and Hermeticism From Antiquity to Modern Times. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- ^ Anon, Hermetica – a new translation, Pembridge Design Studio Press, 1982

- ^ Hermetica. 1992.

[By order of appearance] Arnobius, Lactantius, Clement of Alexandria, Michael Psellus, Tertullian, Augustine, Lazzarelli, Alexander of Hales, Thomas Aquinas, Bartholomew of England, Albertus Magnus, Thierry of Chartres, Bernardus Silvestris, John of Salisbury, Alain de Lille, Vincent of Beauvais, William of Auvergne, Thomas Bradwardine, Petrarch, Marsilio Ficino, Cosimo de' Medici, Francesco Patrizi, Francesco Giorgi, Agostino Steuco, Giovanni Nesi, Hannibal Rossel, Guy Lefevre de la Boderie, Philippe du Plessis Mornay, Giordano Bruno, Robert Fludd, Michael Maier, Isaac Casaubon, Isaac Newton

- ^ Hermetica. 1992.

[T]he Suda around the year 1000: "Hermes Trismegistus [...] was an Egyptian wise man who flourished before Pharaoh's time. He was called Trismegistus on account of his praise of the trinity, saying that there is one divine nature in the trinity."

- ^ Hermetica, The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. 1992.

The Teachings of Hermes Trismegistos, which located the roots of Hermetism in Posidonius, the Middle Stoics and Philo, all suitably Hellenic, but detected no Christianity in the Corpus.

- ^ Hermetica. 1992.

The possibility of influence running from Hermetic texts to Christian scripture has seldom tempted students of the New Testament.

- ^ Corpus Hermeticum XIII.3.

- ^ Copenhaver, Brian P. (1995). Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521425438.

- ^ Jowett, B. (2018). Timaeus (Annotated). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 9781724782205.

- ^ Salaman, Clement (2013). Asclepius: The Perfect Discourse of Hermes Trismegistus. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472537713.

- ^ Hermetica, The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. 1992.

[I]n the well-known gnomic form they found a Greek vehicle ready made for a Hellenic audience.

- ^ Bull, Christian H. (17 July 2018). "The True Philosophy of Hermes". Brill.

- ^ Secretum secretorum – An Overview of Magic in the Greco-Roman World

- ^ Fowden, Garth, The Egyptian Hermes : a historical approach to the late pagan mind (Cambridge/New York : Cambridge University Press), 1986

- ^ Jean-Pierre Mahé, "Preliminary Remarks on the Demotic "Book of Thoth" and the Greek Hermetica" Vigiliae Christianae 50.4 (1996:353-363) p.358f.

- ^ See R. Jasnow and Karl-Th. Zausich, "A Book of Thoth?" (paper given at the 7th International Congress of Egyptologists: Cambridge, 3–9 September 1995).

- ^ "Historical References in the Hermetic writings," Transactions of the Third International Congress of the History of Religions. Oxford I (1908) pp. 196-225 and Personal Religion in Egypt before Christianity. New York: Harpers (1909) pp. 85-91.

- ^ "Introduction". Hermetica, The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. 1992. p. LVII.

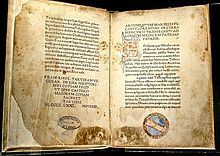

- ^ Among the treasures of the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica in Amsterdam is this Corpus Hermeticum as published in 1471.

- ^ Mahé, Hermès en Haute Egypte 2 vols. (Quebec) 1978, 1982.

- ^ J. Gwyn Griffiths (October 1993). "A New Translation of the Hermetica - Brian P. Copenhaver: Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction". The Classical Review. 43 (2). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ John Monfasani (December 1993). "Brian P. Copenhaver, Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asdepius in a New English Translation with Notes and Introduction". The British Journal for the History of Science. 26 (4). Cambridge University Press.

Bibliography

- Copenhaver, Brian P. (Editor). Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction (Cambridge) 1992. ISBN 0-521-42543-3 The standard English translation, based on the Budé edition of the Corpus (1946–54).

- (Everard, John). The Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus (English), Translated by John Everard, Printed in London, 1650

- Fowden, Garth, The Egyptian Hermes : a historical approach to the late pagan mind (Cambridge/New York : Cambridge University Press), 1986.

- Mead, G.R.S. (Translator) Thrice Great Hermes: Studies in Hellenistic Theosophy and Gnosis, Volume II (London: Theosophical Publishing Society), 1906.

- Latham, M.L. (Translator) Corpus Hermeticum: The Power & Wisdom of God (Falcon Books Publishing) 2020. ISBN 978-0995769229.

External links

- The Corpus Hermeticum. G. R. S. Mead's translations taken from his work, Thrice Greatest Hermes: Studies in Hellenistic Theosophy and Gnosis, Volume II. (The Gnostic Society Library)

- Everard's translation The Divine Pymander in XVII books at Adam McLean's Alchemy Web Site

- Jeremiah Genest, Corpus Hermeticum

- Ἑρμου του Τρισμεγιστου ΠΟΙΜΑΝΔΡΗΣ – Greek text of the Poimandres

- The Hermetic Order History and introduction to hermeticism including excerpts from the Corpus Hermeticum