User talk:Apaugasma

A barnstar for you!

|

The Original Barnstar |

| For your recent edits to Ibn Wahshiyya. Thank you for bringing a scholarly perspective based on recent research to the article! Cerebellum (talk) 11:21, 24 January 2021 (UTC) |

Apaugasma, you seem to know what you're talking about! I'm working on Ibn Wahshiyya's Nabataean Agriculture right now, so if you ever have a moment to spare would you mind reading through it and letting me know what you think? I know the prose is rough, I need to clean it up, but I’m more worried about any errors of fact or interpretation. Until I saw your edit summary I didn’t know that Nasr was a fringe author, I’ll remove my citation to him but there are probably other mistakes lurking! --Cerebellum (talk) 11:27, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- Dear Cerebellum, thank you very much! Thank you also for motivating me to put a bit of extra effort into this; it most certainly works! I've been busy all day writing a series of comments and suggestions on your wonderful article, which I've posted on its talk page. Thanks again, Apaugasma (talk|contribs) 21:48, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

Questions

Can I ask whether you know much about the origins and development of the Greek four-stage colour-coded alchemical process ending with iosis (rubedo, rubefaction) via xanthosis, etc.? It was this connection, with the end product being purple and purple being the highest colour, indicating the (spiritual) purity of the rarefied material and somehow conceiving of purple as equal or greater than gold, or rubefaction as the final purifying stage in the production of "gold", that I am especially interested in. Reference was made to some Leiden papyri in Liz James's Light and Colour in Byzantine Art and some papers cited therein, but I'd like to know more about colour in the beginnings of alchemy and the first millennium of alchemy in the Greek East. Most work seems to favour the Arabic or Latin traditions of later centuries. GPinkerton (talk) 17:53, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- Also, it'd really help editing if you were to use the Template:Cite book and other such templates. If you use the WP:VisualEditor you can use the automatic citation formatting tool: one only needs to copy-and-paste in a DOI, URL, or an ISBN and it will do most or all of the work for you. Many thanks for your efforts thus far! GPinkerton (talk) 18:03, 24 January 2021 (UTC)

- Dear GPinkerton, I'm sorry to disappoint you, but I don't know much about Greco-Egyptian and Byzantine alchemy (a gap I intend to fill, though there are many!).

- What I do know is that one of the four original books of pseudo-Democritus was called On Purple (now part of the Physika kai mystika, but also separately preserved in a Syriac version; see Martelli, Matteo 2013. The Four Books of Pseudo-Democritus. Sources of Alchemy and Chemistry, 1 = Ambix, 60, Supplement 1. Maney Publishing, p. 19). Like the other three books of pseudo-Democritus, it contained information on the production of dyes: this one on how to dye wool purple, the other three on how to 'dye' precious stones and on how to 'dye' metals gold and silver (these 'dyes' were probably rather chemical reagents, a terminology still found in Arabic and Latin alchemy). More specifically, On purple contained recipes for how to dye wool purple by using two natural substances (bryon thallasion and lakcha, see Martelli 2013, p. 11), which could be used as a substitute for the expensive Tyrian purple (also known as murex, the colour of emperors; Martelli 2013, p. 17). Similar recipes to dye fabrics purple are also contained in the Leiden and Stockholm papyri (Martelli 2013, p. 6).

- Starting from this, we may perhaps hypothesize that, given the nature of purple as a status symbol comparable to how we regard gold today, the Byzantine alchemists commenting on pseudo-Democritus were especially proud of their capability to artificially create purple? Perhaps they associated purple 'dye' (probably involving a 'spirit' or highly volatile substance?) with the capacity to perfect nature, somewhat like later alchemists did with the 'elixir' or 'stone' that could perfect metals in order to create gold? Much further research is certainly needed, but this is as far as I get, on this evening, with my very limited knowledge. Apaugasma (talk|contribs) 00:37, 25 January 2021 (UTC)

Thrice-thanks! that's a magnificently more-than-adequate answer! I am very grateful! It is of note that many of the patristic authors refer to dyeing with purple as the basis of various metaphors for both positive and negative (but always indelible) characteristics, doubtless referring to Eclogue 4 (if I remember right) of Vergil and the pun on dyeing/baptism (βάπτω). One of the pseudepigrapha mentions a purple light emanation during the Harrowing of Hell. I'm working on this for my own research on coloured stones in the art of the relevant period. While I know the authors were often concerned with the σμαράγδας (perhaps represented in architecture with verde antico) but do you know of any mentions of porphyry (small p) in the esoterica of any language? GPinkerton (talk) 01:18, 25 January 2021 (UTC)

- @GPinkerton: Well, there's of course the Dēmokritou peri porphyras kai chrysou poiēseōs that is now part of Physika kai mystika as mentioned above. But since pseudo-Democritus' Physika kai mystika is the earliest known alchemical text and was regarded by all later Greek alchemists as the single most authoritative source, I suspect that you will find much of interest throughout the Greek alchemical literature. It strikes me as strange that someone would be researching coloured stones in the Byzantine period without consulting the alchemists, for whom the colouring of stones was one of their main businesses? Since you seem to read Greek fluently, I strongly suggest you just go through the actual texts, which are generally quite short, and even taken all together fit in one volume of c. 460 pages (vol. II of Berthelot, Marcellin and Ruelle, C. E. 1888. Collection des anciens alchimistes grecs. Vols. I-III. Paris: Steinheil, undoubtedly available online; vol. III has French translations of all texts). Note, though, that Berthelot and Ruelle's edition is very poor, so where available it is better to consult critical editions (mainly Martelli 2013 as cited above for pseudo-Democritus and the Les Alchimistes grecs series published by Les Belles Lettres). For secondary reading, I suggest Nicolaïdis, Efthymios (ed.) 2018. Greek Alchemy from Late Antiquity to Early Modernity. Turnhout: Brepols (a collection of essays, mainly by top tier experts); Magdalino, Paul and Mavroudi, Maria (eds.) 2006. The Occult Sciences in Byzantium. Geneva: La Pomme d'or (an older collection of essays), and perhaps (if you read Italian) Martelli, Matteo 2019. L’alchimista antico: Dall'Egitto greco-romano a Bisanzio. Milano: Editrice Bibliografica.

- I strongly suspect that the fascination for purple was a typically Roman/Byzantine phenomenon, but of course it may have left some traces in the early Arabic literature. If I ever come across anything, I'll be sure to contact you! You may also want to contact Matteo Martelli, who is the world's foremost expert in technical Greek alchemy. In the meanwhile, I'd be very interested in some references for the Patristic allusions to purple dying (that the 'dye' would penetrate the whole of the substance and thus would be indelible was one of the ways in which alchemists differentiated 'their' dying from 'regular' dying), as well as to the pun on dying/baptism? Apaugasma (talk|contribs) 16:01, 25 January 2021 (UTC)

- Apaugasma, Thanks so much for this! I was just reading the Martelli paper and made a note to contact him or his team. I am keen to know what the authorities had to say on stones, but particularly building stones, marbles, and particularly porphyry. There is a fascinating late reference to a tradition involving the casting of porphyry columns in vats (obviously stemming from a confusion with the purple dye which shares the rock's name) cited in a footnote to Fabio Barry's "Walking on Water" on marble's historical conception of having been made from liquid by various means. Somewhere there is also reference in an Arabic source to certain porphyry columns in a mosque in Cairo which had been allegedly manufactured by a djinn (who had been forced to abandon them for one reason or another), and somewhere else there is mention of porphyry spolia in the Great Mosque of Damascus having come from the throne of Solomon (no less). Ibn Jubayr (according to the translation I read) saw porphyry (and green marble) in the very Ka'aba. Unfortunately my Greek is nowhere near good enough to read alchemy without the aid of a translation, though I will want to see the originals.

- βάπτω (I dip, dye, give colour to) is the root and stem of βαπτίζω (I baptize). Because purple dye was the only really colour-fast garment dye in antiquity, it had a special symbolic value and never washed out (and neither did its fishy smell). Fetishizing purple dye was widespread in the ancient east long before the Romans; the Hebrew Bible frequently refers to purple, and early exegetes treated of these usages, and it may even have been tekhelet, possibly made from the same or similar snails by another method. (One of the most fundamental things is that "purple" (and colours in general) need not necessarily be the colour purple, though the most desirable seems to have been the blood/rust/wine colour usually represented.) I will give specifics soon. GPinkerton (talk) 16:28, 25 January 2021 (UTC)

- Apologies for copying this from my unpublished research's footnotes; it may be inaccurate and I don't recall exactly what is being said in most of them, though I can find out if necessary. It should be said that these ideas are mine and not (yet) reviewed. There are many more, but these footnotes represent the state of some of my work 2 years ago ... GPinkerton (talk) 17:11, 25 January 2021 (UTC)

Citations

|

|---|

|

- @GPinkerton: Thanks a ton for these! I'm sure they will be of some use to me. Sincerely, Apaugasma (talk|contribs) 17:55, 25 January 2021 (UTC)

A barnstar for you!

|

The Rosetta Barnstar |

| For deciphering Wikipedia's alchemical morass in various language traditions; a magnum opus! GPinkerton (talk) 14:31, 26 January 2021 (UTC) |

- Thank you, dear GPinkerton, I feel very honoured! Apaugasma (talk|contribs) 15:28, 26 January 2021 (UTC)

Hi! Wandered here from the ANI on Yaakov and was intrigued by your explanation of your username. Wondered if, based on your knowledge of greek, you might be able to decipher the last sentence of the lede at Sinemorets to clarify what the Greek name was? Trying to find some better history on this place as the current name is fairly new and thought having the correct Greek transliteration might help. Thanks either way. StarM 00:50, 16 April 2021 (UTC)

- @Star Mississippi: I only have a very superficial command of ancient Greek, and you might get a much better answer from someone who is a native speaker of Modern Greek (which is quite different). Here's a list of people who have volunteered for translating from Greek. However, I will do my best to provide you with an answer using my make-shift skills.

- The name Γαλαζάκι (Galazáki) appears to be compounded of the words γαλάζιο (galázio) ("azure", "sky blue", noun) or γαλάζιος (galázios) ("sky blue", adjective) and the diminutive suffix -άκι (-áki), rendering something like "Little Azure" or "Little Blue". It appears to be a common name for the flowers Veronica persica (birdeye speedwell) and Centaurea cyanus (cornflower) in modern Greek (according to this and this blog respectively, of course not exactly RS, but likely enough since both are small blue flowers). My best guess is that the village's name refers to the azure color of the sea, though there's no way to be certain (the Spanish wiki translates the Bulgarian name as "lugar en el mar azul", "place in the blue sea", but again not a RS).

- Hope this helps, Apaugasma (talk|contribs) 02:51, 16 April 2021 (UTC)

- Thank you very much. Even if not RSes, they're a helpful starting point toward further sourcing. StarM 13:24, 16 April 2021 (UTC)

Gospel of Mark

Just to clarify that I don't actually disagree with the content of what you wrote, just the division between the lead and the body of the article. Achar Sva (talk) 07:41, 23 April 2021 (UTC)

- @Achar Sva: thanks for clarifying that! :)

Just wanted to say thanks

Hey, just wanted to say thanks for taking the time to make Wikipedia better. You're the type of person that makes this site better. Thank you, friend! Much appreciate your help with the article. Rusdo (talk) 04:15, 28 April 2021 (UTC)

- @Rusdo: No problem! You'll probably also like what I did to Gospel of Mark. Apaugasma (talk|contribs) 04:35, 28 April 2021 (UTC)

- I do like it and I think it makes for a better article. I don't understand this knee-jerk reaction by some people against nuance and qualifications. That's what scholarship is all about. Pretending like there's a consensus in scholarship when there really isn't helpful. Rusdo (talk) 00:10, 3 May 2021 (UTC)

Apollonius of Tyana

Hi Apaugasma,

A few questions for you about the Apollonius of Tyana article.

1. You put the Francis quote from the sources section to the historical facts section. May I ask why? Francis is specifically discussing the sources involved. This quote is a better fit in the sources section IMHO.

2. I checked the source for this quote: "This led to controversy, as critics believed Gibbon was alluding to Jesus being a fanatic." It was simply not there in the B.W. Young article. Unless I miss something, I think this is out of place.

3. "Hilton Hotema compared Apollonius to Jesus by noting that there is much historical data surrounding the life of the Tyanean, but that Jesus is unknown outside of the New Testament." This is well outside mainstream scholarship and demonstrably false. If this quote is included, a note should be made regarding this. There is ample evidence for Jesus outside the New Testament and virtually no early evidence for Apollonius, as demonstrated in the Wikipedia article.

Thank you. Rusdo (talk) 04:28, 17 May 2021 (UTC)

- Dear Rusdo, since your comment directly deals with article content, I copied it to the article talk page and answered it there. If you want to get the attention of other editors in talk pages, you can do so by using a template such as {{u|Apaugasma}}, which will 'notifify' or 'ping' the editor involved. Apaugasma (talk|contribs) 14:12, 17 May 2021 (UTC)

Thanks for the discussion

It would probably be a good idea for you to take a break from my talk page because you seem to have run out of ammo. Thanks. Viriditas (talk) 21:31, 22 May 2021 (UTC)

- @Viriditas: yes, you're absolutely right. Thank you very much for your understanding. Apaugasma (talk|contribs) 21:43, 22 May 2021 (UTC)

Smile at others by adding {{subst:Smile}} to their talk page with a friendly message.

Hieroglyphs, decipherment of

Hi Apaugasma! First off, thanks for the warm welcome and for the balanced edits :-). One request, though: I think "[...] was able to identify the phonetic value of a few Egyptian hieroglyphs" gives the wrong impression. This suggests that Ibn Washiyya was following the correct method like an early Young / Champollion, as per Dr. El Daly's claims. I would be very excited if that were true, but looking e.g. at the picture shown with the article (from Dr. El Daly's presentation), it clearly is not:

Going through the list from the upper left, 𓊰 is not a uniconsonantal sign at all, certainly not "aleph", 𓏌𓏤 is /nw/ + determinative stroke, not "y", 𓏏 𓏥 is /t/ + plural strokes and not "q", 𓉻 is ayn+aleph (the word "great"), not "g", the next character 𓏌 is /nw/ again, now interpreted as "b", 𓊹𓊹 "two gods" (nTr.wy?) is certainly not "k" and so forth ... I could go on for the rest of the chart: it is not just that the phonetic values are misidentified but that word signs are interpreted as phonetics and the author clearly did not even understand which signs belong together. This impression is confirmed by a quick glance through the translation of the work linked to in the article: whole groups of glyphs are given allegorical translations "if a man was poisoned they would write it with XYZ glyphs" with no basis in the actual text displayed. So, if any glyphs were identified correctly I would ascribe that to mere chance (sadly, again - if the work had been done 1,000 years ago, I would be extremely excited).

I think the reason why this never gets called out is because the number of reporters that can read Hieroglyphs and Arabic is vanishingly small if not zero. I would give Ibn Washiyya credit for trying and for his assumption that signs could be read phonetically (rather than just allegorically / as ideographs) - in itself an important step. But "correctly identified some signs" gives the wrong impression IMHO, especially since this has been hyped so much in the media and there has been no critical reporting whatsoever (outside of specialist circles). Can we find a better way to phrase this? I struggled, that's why I took the identification part out completely in the lead section. — Preceding unsigned comment added by MikuChan39 (talk • contribs) 12:35, 30 May 2021 (UTC)

- Hi MikuChan39! Thank you for posting here. However, since what you wrote could be of some benefit to future editors of the article, I moved it to the article's talk page and replied to you there. If you want to notify other editors that you wrote something on a talk page you can do so by using templates such as {{u|Apaugasma}} or {{ping|Apaugasma}}. Last but not least, don't forget to sign your posts by typing four tildes (~~~~) at the end. ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 18:23, 30 May 2021 (UTC)

June 2021

Please stop your disruptive editing.

Please stop your disruptive editing.

- If you are engaged in an article content dispute with another editor, discuss the matter with the editor at their talk page, or the article's talk page, and seek consensus with them. Alternatively you can read Wikipedia's dispute resolution page, and ask for independent help at one of the relevant noticeboards.

- If you are engaged in any other form of dispute that is not covered on the dispute resolution page, seek assistance at Wikipedia's Administrators' noticeboard/Incidents.

If you continue to disrupt Wikipedia, you may be blocked from editing. Reverting the deletion of material added by a blocked sock is...well, it's about the worst explanation one can give. Drmies (talk) 01:14, 27 June 2021 (UTC)

- @Drmies: These edits were originally added by a number of editors who have recently been blocked for promotional editing (see the recent thread at ANI). However, as I discussed with Notfrompedro (the user who carried out the mass-reverts), quite a few of these edits were actually quite helpful from an encyclopedic point of view. I've been going through them very carefully, only reinstating those that do contribute valuable content and are compliant with content policy (mostly NPOV, which a lot of the edits also failed). I've had some discussions about some of these reinstatements (see, e.g., here and here), but it's not always easy to decide which edits are good and which are not, so that is to be expected. In any case, I believe that we should preserve good content, even if it was added by blocked editors. Would you please reconsider the action you took here? Thanks, ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 01:32, 27 June 2021 (UTC)

- Apaugasma, that ANI thread alone is as clear as mud as a rationale for restoring this content, but I'll take your word for it. I would, however, change that edit summary a bit--go ahead and restore what you believe to be right. Sorry to make you go through that, but none of this was just very transparent. Drmies (talk) 01:47, 27 June 2021 (UTC)

- I reverted myself for a couple of edits, but reading through the "Days of Creation" article, I can't help but wonder why that is worth inserting all over the place. I can't find a single review of it, and only a few mentions--here someone points to it cause they published in it, and this tells me it's basically a proceedings collection from a conference in Tajikistan. So that it is valuable content verified by a valuable source, I am not convinced. Drmies (talk) 02:02, 27 June 2021 (UTC)

- @Drmies: I can see how this must be confusing. What about the following for an edit summary: "this content was originally added by a blocked editor and reverted for that reason, but I am restoring it because it complies with content policy and improves the encyclopedia; please discuss at the talk page if you disagree"? I usually try to be as clear as possible in edit summaries, but I clearly goofed up on this one.

- Could you be more specific which edit you're discussing? The blocked editors indeed tended to add the same content to a number of related articles, but on the whole they did add a lot of different content of varying degrees of quality. I think each one of them is open for discussion, but I need to know which one you mean, and which source it is using. Shafique Virani, though by no means a top scholar in the field, generally is a reliable source (see, e.g., his contributions to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, the standard reference work for Islamic studies [1]). ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 02:24, 27 June 2021 (UTC)

- @Drmies: the source you're referring to is probably Virani, Shafique N. 2005. "The Days of Creation in the Thought of Nasir Khusraw" in: Nasir Khusraw: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow. Edited by Sarfaroz Niyozov and Ramazan Nazariev. Khujand, Tajikistan: Noshir Publishing House, pp. 74-83 ([2]). Its worth may perhaps be gauged from the fact that it was republished online by the Institute of Ismaili Studies (here), the prime research institute for everyone dealing with Ismailism. This is as reliable as it gets (the IIS has a problem of being funded by Ismaili organizations, but it is extremely well-respected in the field), though that does not necessarily mean that any individual edits by the blocked editors based on it are appropriate. Perhaps it is better to discuss these edits at the talk pages of the articles concerned. In the mean time, will you self-revert, or shall I revert your edits? Thanks, ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 13:24, 27 June 2021 (UTC)

- That edit summary is fine. Yes, go ahead and undo--if you can restore the previous version so I don't get a ping every time that would be great. Ha, you got a ton of them yesterday of course. But yes, that (above, "Days of Creation") was the one that troubled me, thanks, but I'll accept your analysis and trust your expertise. Drmies (talk) 13:39, 27 June 2021 (UTC)

- @Drmies: the source you're referring to is probably Virani, Shafique N. 2005. "The Days of Creation in the Thought of Nasir Khusraw" in: Nasir Khusraw: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow. Edited by Sarfaroz Niyozov and Ramazan Nazariev. Khujand, Tajikistan: Noshir Publishing House, pp. 74-83 ([2]). Its worth may perhaps be gauged from the fact that it was republished online by the Institute of Ismaili Studies (here), the prime research institute for everyone dealing with Ismailism. This is as reliable as it gets (the IIS has a problem of being funded by Ismaili organizations, but it is extremely well-respected in the field), though that does not necessarily mean that any individual edits by the blocked editors based on it are appropriate. Perhaps it is better to discuss these edits at the talk pages of the articles concerned. In the mean time, will you self-revert, or shall I revert your edits? Thanks, ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 13:24, 27 June 2021 (UTC)

The Arabic Hermes

You appear to be an extremely knowledgeable person to me. Will come to visit you from time to time to discuss few things or to get some book recommendations on the history of philosophy, religion and science if you don't mind. I have started reading Kevin Van Bladel's "The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science." Interesting study. But the book I suppose suffers from some Hellenocentric biases. I don't know. That is just an opinion. I haven't even finished the book yet. Have you come across this term before? I mean, Hellenocentrism? I suppose you have. The article is not an well developed one. Need more references to enrich that entry. Anyways, Bladels' book is great. Learning many things from it. Wanted to let you know that I came to know of this book from one of your comments in a talk page. And yes, pardon my English, I am not a native speaker. Best wishes for you. Mosesheron (talk) 17:58, 1 July 2021 (UTC)

- @Mosesheron: Thank you for the compliments! You're always welcome here to ask for references; I would be glad to help if I can.

- As for Hellenocentrism, I had not yet come across the term itself, but judging from the article it can refer to several different concepts which do sound familiar:

- Understood as 'Ancient Greek exceptionalism' (i.e., the idea that the cultural accomplishments of the ancient Greeks happened in complete isolation from the surrounding cultures and that they represent some kind of 'miracle'), it's of course a well-known position in the older historiography of philosophy and science which slowly but surely is getting exposed as the ahistorical nonsense it really is. The main problem with it, as I see it, is that it entirely ignores the fundamental role played by textual transmission: what we do and do not know about the cultural accomplishments of people who lived more than 2000 years ago is entirely determined by the people who lived in the two intervening millennia: its their interests, their preservation efforts, their politics, and their military successes and failures which have resulted in the survival of some texts and the perishing of others. Basically, most of what we know about the ancient Greeks is due to the efforts of Byzantine copyists, their intellectual (Eastern Christian) predilections, and the fact that Constantinople remained unconquered until the 15th century. If Alexander had never conquered the cities of ancient Egypt and Persia, and if the Muslims wouldn't have done the same a thousand years later, we might have had access today to a rich Coptic and Persian literature similar to what we now have in Greek. There is no doubt in my mind that if that would have been the case, the whole idea of the 'Greek miracle' would have been an obvious absurdity that no one would even ever had thought of.

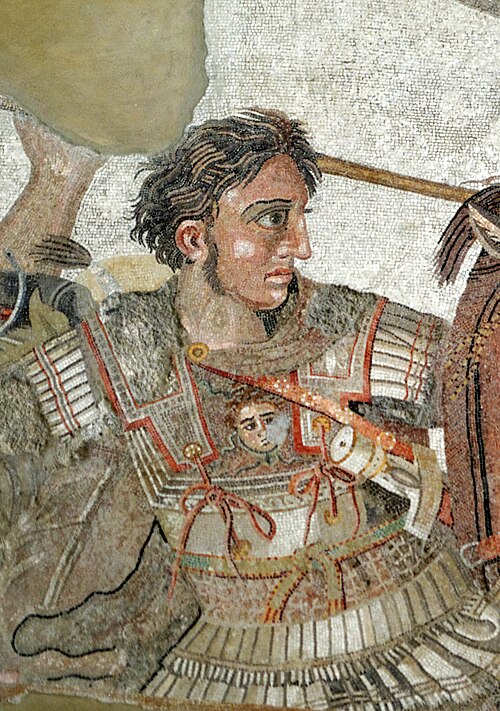

Alexander the Great, the power-hungry student of Aristotle who started it all. Also became the subject of a medieval Romance, and appeared in some pseudo-Aristotelian treatises such as the Secret of Secrets and the Treasure of Alexander. The latter claims that Aristotle received his wisdom from Hermes Trismegistus, conveying the belief that philosophy and science originated neither in Greece nor in Persia, but in the divine grace of God. - However, there also appears to be a secondary meaning of the term 'Hellenocentric' –one that the article strongly focuses on– which seems more closely related to identity politics, and which in my view wrongly blames modern (Western) historians for the vagaries of textual transmission as outlined above. That ancient Greek thought uniquely influenced all later civilizations west of India is not the result of some kind of Eurocentric bias, but merely a historical fact (and one largely due to the conquests of Alexander, which set into motion a process of Hellenization that had already reached levels of near-universality in early Byzantine Egypt and Sassanian Persia). That history books mainly focus on ancient Greek thought is partly due to this unique influence, and partly due to the fact that we have actual ancient Greek texts dating from that period to actually base our history books on. The simple reality is that we do not have an extant Coptic or Persian literature even remotely similar to what we have in Greek. Ancient Egyptian and Persian thought is all but entirely lost, and though what is left has not nearly been studied well enough, most of the pithy survivals were already under thorough Hellenistic influence, and just aren't of the quality and depth of what we have in Greek (and later, in Arabic). Again, this is entirely due to textual transmission, not to any inherent inferiority of Egyptian or Persian thought. But it still is the reality we have to deal with today, and the idea that modern (Western) historians are somehow trying to cover up or deliberately ignoring the evidence is itself a dangerous and damaging delusion.

- As such, I do not believe that van Bladel is writing from a 'Hellenocentric' point of view: he is deliberately investigating Middle Persian, Syriac and Arabic texts in order to recover some of the rich intellectual traditions of the late antique and medieval Middle-East. The fact that most of these traditions go back on Greek and Hellenistic thought is not of van Bladel's choosing. Neither is the fact that the Sassanids were already engaging in an early form of identity politics by claiming that Alexander 'stole' all supposed Greek knowledge from the Persians, a theme that would reappear in many different guises in medieval Arabic literature. What exactly the ancient Greeks from the 6th century BCE owed to the Persians has been the subject of some speculation among 20th-century historians, but what Khosrow I claimed about this 1200 years later in the 6th century CE is simply of no historiographical value. Again, the actual facts about this are long lost, and it is wrong to blame modern historians for this.

- With all this said, there is also the (different) phenomenon of Eurocentrism, which is a very real and much more insidious problem in Western historiography. Actually, the very idea that the ancient Greeks were somehow 'European' lies at the core of it, though there's of course also the neglect of anything not perceived to be 'European'. In fact, 'Europe' is a cultural construct dating from the 18th century, and the ancient Greeks really had nothing to with it: their world was part of the larger eastern Mediterranean, and they were looking to the inhabitants of Egypt and Mesopotamia as cultural 'relatives', not to the ancient Celts living in what is now Western Europe. Greek philosophy and science spread over Egypt, the Levant, and Persia about 1500 years before it finally reached Western-Europe (during the so-called Renaissance of the 12th century). Like ancient Greek culture itself, the history of Greek influence is a non-European one at least until the late Middle Ages. However, (Eurocentric) books on history of science or philosophy generally skip from ancient Greece to the Renaissance or the Early Modern period, leaving a huge gap that actually constitutes the greatest part of the story. In this context, Peter Adamson's History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps is a wonderful initiative. ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 00:44, 2 July 2021 (UTC)

It was really enlightening. However, do you believe that modern historians have genuinely attempted, or are still attempting, to reconstruct the cultural context in which ancient Greece flourished, with all of its knowledge of philosophy, theology, and so on? Was it that difficult, given the fact that they have “successfully reconstructed" many aspects of history that were almost unknown to us? I'm sure you've considered the time period between the so-called first philosopher of ancient Greece, Thales, and the "all-knowing" Aristotle, in whose figure we see the culmination of nearly all ancient knowledge? How could they achieve so many things within such a short period of time? What are the real sources of pre-Socratic philosophy, theology, and so on? Did it all begin with them? If the answer is no, then, who were their real inspirations? People like Martin Bernal et al might well be wrong in their theses, but what really have the mainstream historians taught us about this aspect of intellectual history? I've been looking for a few works on the history of ancient philosophy, theology, sciences, and other subjects that explore the origins and sources of pre-Socratic philosophy in depth, but to my surprise, I have found none. Now that maybe because I am not an expert in the filed or a student of the history of philosophy and sciences like you. But again why are they so scarce if they really exist, if such works exist at all? Most books or journal papers I read start with the pre-Socratics, with an introduction that largely rejects rather than recognizes the contributions or contacts with other civilizations in a very smart way. They frequently spare a few lines to demonstrate how primitive and mythological other civilizations were, while claiming that the Greeks were unique and original in such and such ways. I made a comment on the Talk Page of the pre-Socratic philosophy about its sources and origin few months ago, which two devoted editors took very seriously. What do we come know about its origin and history from that page now? The straightforward answer is nothing. I am not of course undermining their efforts. Perhaps they did their best. Or perhaps they thought such little description was sufficient for it. Would you kindly recommend me some works that discuss the origins and sources of pre-Socratic philosophy in depth? Lastly, I thank you for your comment. It offers some ideas that our academics frequently fail to express. Best wishes. Mosesheron (talk) 17:13, 2 July 2021 (UTC)

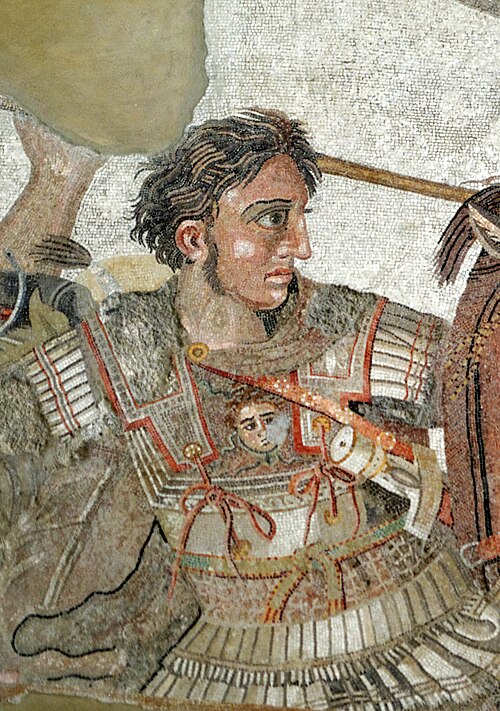

Hermann A. Diels (1848–1922). His collection of Presocratic fragments, Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, is still used by scholars today. Also coined the term doxography, and reconstructed several ancient Greek doxographies in his Doxographi Graeci. - @Mosesheron: it's all about textual transmission, really. To understand this, first you need to understand what our knowledge of ancient philosophy is actually based on.

- Did you know that we do not have even one work from a Presocratic philosopher? All of our knowledge about Presocratic philosophy is based on what we can glean from Plato and Aristotle (who have already been shown by Cherniss 1935 to be rather unreliable when it comes to the Presocratics), and from the fragments that can be found in late (and very unreliable) doxographical collections such as those compiled by Arius Didymus (fl. 1st century BCE), Aetius (fl. c. 100 CE) and Diogenes Laërtius (fl. 3d century CE), as well as in the works of some Church Fathers and other later thinkers (Cicero, Galen, Alexander of Aphrodisias, Plotinus, Neoplatonic commentators on Aristotle such as Simplicius, etc.). The most extensive of those later sources are the doxographical collections, but they're also the least reliable: to know how unreliable they really are, it suffices to look at what they say about Aristotle and Plato (whose actual works we do have), which often doesn't even remotely resemble the ideas found in Plato's and Aristotle's extant works. So the whole venture of reconstructing Presocratic philosophy is based on puzzling with mostly unreliable late fragments, and much, much speculation. But at least we do have the Greek works just mentioned to glean the fragments from, which is entirely due to medieval Byzantine copyists and geopolitical vagaries as explained above. On the non-Greek (Egyptian, Levantine, Mesopotamian, Persian) contemporaries of Plato and Aristotle, we have absolutely no textual evidence (apart from some travel tales and myths retold by Plato himself, who in this case constitutes an even less reliable witness).

- But there are also important differences between the Presocratics themselves. Of Empedocles (c. 500 – c. 430 CE, not so long before Plato, c. 428 – c. 348 BCE), we have been able to reconstruct two almost complete poems. Of Thales (c. 625 – c. 550 BCE), on the other hand, we have not even one authentic fragment, and only some sparse and very questionable testimonies from Aristotle (i.e., we know almost nothing about him). So what are we going to say to someone who comes asking not about Thales himself, but about Thales' sources? There is a broad consensus today that in all probability, it did not start with Thales, and that he learned what he knew (whatever that was) from Mesopotamian and perhaps also from Egyptian itinerant teachers. But here we have entered the field of complete and utter speculation. There are no sources. This is an important point to grasp, because it both answers all your questions and leaves you entirely puzzled. More precisely, it leaves you as puzzled as scholars are, and I assure you that if there was anything that scholars could do to arrive at a better understanding, however slight, they would do it in a heartbeat.

- But the puzzle is unsolvable, because almost all of its pieces are lost. There are some Babylonian clay tablets which contain practical instructions related to sciences like astronomy and medicine, some Egyptian papyri dealing with medicine and mathematics, etc. These are very similar in content to extant ancient Greek papyri such as the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, i.e., mainly practical in nature and generally very far removed from the highly sophisticated texts dealing with philosophy and science, which also in the ancient world were very rare and constituted a very small minority of the written material (actually, they were more akin to jealously guarded treasure). This kind of text, which undoubtedly also existed in many other languages than Greek, did not easily end up somewhere buried under the sand, but needed to be diligently copied every few centuries or so to survive, which means that its survival depended on the existence of a scribal class who had the knowledge and the means to read, understand, translate, and copy material. This class of people often perished along with the empire that supported it, although there often was also some form of continuity (most notably in Christian monasteries, or in special cases such as when the descendants of Sassanian administrative functionaries were restored to power by the early Abbasids, most famously the Barmakids). For example, we know that there was an extensive philosophical literature in Middle Persian which was developed under the Sassanids (note, however, that this literature was already thoroughly Hellenistic), but which is almost entirely lost today (some traces of it may be found in the scanty Zoroastrian literature that does survive, such as in the Bundahishn; some works also survive in Arabic translation, such as part of the Arabic Hermetica). When it comes to ancient (before c. 300 BCE) non-Greek philosophical literature though, this was all swept away by the Macedonian, Roman, and Parthian conquests, and there's just nothing left for us but speculation.

- Now scholars generally don't write books based on nothing but speculation (OK, Martin Bernal did, but there's a reason why we call his work

pseudo-historic

around here), so that's why you're not finding such. I don't know any real good reference for pre-Greek science (i.e., Babylonian and ancient Egyptian science), but I highly recommend checking the first chapter of Lindberg, David C. (2008). The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, 600 B.C. to A.D. 1450 (2d ed.). University of Chicago Press., which probably refers to some good sources on this in the bibliography (actually, the whole book is worth reading in itself, as it is the standard introduction to the history of science west of India). For Presocratic philosophy, there's Cherniss, Harold F. (1935). Aristotle's Criticism of Presocratic Philosophy. New York: Octagon Books., which is of course outdated in many ways, but remains the go-to classic when it comes to source criticism with regard to the Presocratics. For Presocratic philosophy itself, there are the well-known standard introductory works by scholars such as W. K. C. Guthrie and Jonathan Barnes (especially Guthrie is still very often cited), but I suspect you will find a much more up-to-date historiographical approach (as well as some interesting references) in Laks, André; Most, Glenn W. (2018). The Concept of Presocratic Philosophy: Its Origin, Development, and Significance. Princeton University Press. There's much more where that came from, so please feel free to ask.

- I too wish you all the best, ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 01:11, 3 July 2021 (UTC)

- I cannot thank you enough. Of course, I will come back to you for more references. But for now I think I will have to meditate upon your comment and look into the sources you have mentioned in order to fully comprehend what you have said. Best regards. Mosesheron (talk) 15:04, 3 July 2021 (UTC)

Removing legitimate talk page comments

![]() Please do not delete or edit legitimate talk page comments, as you did at Talk:Shem HaMephorash. Such edits are disruptive, and may appear to other editors to be vandalism. If you would like to experiment, please use your sandbox. Thank you. Skyerise (talk) 11:06, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

Please do not delete or edit legitimate talk page comments, as you did at Talk:Shem HaMephorash. Such edits are disruptive, and may appear to other editors to be vandalism. If you would like to experiment, please use your sandbox. Thank you. Skyerise (talk) 11:06, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

- @Skyerise: I can assure you that was in good faith, and that I don't mind you reverting it at all. It seems that the discussion is actually taking place in the thread above, and I just thought that it would be better if those who read the notifications at the Wikiprojects would be directed to that thread rather than to an empty poll. It was not my intention to vex you. Please accept my sincere apologies. ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 11:26, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

- Yes, that's the intention. The discussion should take place in a separate section from the poll. It's cleaner that way and the closer can see the stated opinions more clearly. However, it is a poll and I've been informed by an admin that it's a perfectly legitimate thing to do. Those who don't put their opinion in the poll will simply not have their opinions counted. Skyerise (talk) 11:29, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

- @Skyerise: Yeah it sure is legitimate. I was just going to propose adding something like this, but you've already done so, so that's great! I guess that other editors have some resistance to this because usually a poll (or a request for comment, which as far as I can see is the same) is only started after some discussion has taken place on the talk page (this is explicitly mentioned in WP:RFCBEFORE). Perhaps we could still add an {{rfc}} template to it? That way, the RfC is listed and random editors are notified by the feedback request service. I've never done this before though, so I'm somewhat hesitant about it. Thanks, ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 11:49, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

- I don't mind if someone adds an RfC to it. If that makes it necessary to change the heading, just make it a subheading under mine, since I've already notified two interested WikiProjects using my heading. Skyerise (talk) 12:23, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

- @Skyerise: Yeah it sure is legitimate. I was just going to propose adding something like this, but you've already done so, so that's great! I guess that other editors have some resistance to this because usually a poll (or a request for comment, which as far as I can see is the same) is only started after some discussion has taken place on the talk page (this is explicitly mentioned in WP:RFCBEFORE). Perhaps we could still add an {{rfc}} template to it? That way, the RfC is listed and random editors are notified by the feedback request service. I've never done this before though, so I'm somewhat hesitant about it. Thanks, ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 11:49, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

- Yes, that's the intention. The discussion should take place in a separate section from the poll. It's cleaner that way and the closer can see the stated opinions more clearly. However, it is a poll and I've been informed by an admin that it's a perfectly legitimate thing to do. Those who don't put their opinion in the poll will simply not have their opinions counted. Skyerise (talk) 11:29, 4 July 2021 (UTC)

Empty Tomb Assumption Narrative — is the source good enough?

@Apaugasma:, I was wondering if you'd like to weigh in on a discussion of sources over at Empty tomb. The question is over the validity of an assumption narrative lying at the heart of the empty tomb story in Mark. It seems to me that according to the source in question, this is problematic and probably not a mainstream or even a significant minority view. I know you appreciate taking sources seriously and figuring out what they're saying. I'd love to have your take. Rusdo (talk) 14:05, 8 July 2021 (UTC)

Thank you

Thank you Apaugasma for informing the mistake in my draft article. I moved the page title of the article 'Paracelsus' to Philips Paracelsus. It will be more informative are easy to search. Regards, Hrishikesh Namboothiri V VNHRISHIKESH (talk) 06:43, 20 July 2021 (UTC)

Repeated links in See also section

Thank you for you comments on my talk page. I see that you have restored some of the "see also" link I removed, but https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Manual_of_Style/Layout#%22See_also%22_section says that the "See also" section should not repeat links that appear in the article's body - and those link are already in the article.— Preceding unsigned comment added by Inf-in MD (talk • contribs) 23:34, 1 August 2021 (UTC)

- @Inf-in MD: yes, in theory you are certainly right. However, I think there are often good reasons to ignore this rule, as I will explain below. The following is partly copied from another talk page where I have made this argument before:

- MOS:SEEALSO says that

as a general rule, the "See also" section should not repeat links that appear in the article's body.

But it also says thatwhether a link belongs in the "See also" section is ultimately a matter of editorial judgment and common sense.

It seems to me that in many cases, these two recommendations are in conflict. - In what is probably the most recent Request for Comments (RfC) questioning the guideline, those who defended it wrote the following (each paragraph from a different user):

The guideline says "As a general rule", so if a link is particularly important and helpful to the reader, it can be repeated in See also. But if this [sc. this guideline] is removed entirely, people will add whatever links they want to draw attention to.

The point of the guideline is to make sure the See also section doesn't get too long, so we're supposed to use it sparingly. If something really is an excellent link to repeat, then you can do it. Note that editors may differ in their interpretion of "excellent", of course. We used to have an editor who would go around removing See alsos, no matter how helpful. He would either incorporate them into the text or remove them. That was a nuisance, but I've not seen anyone do that in a systematic way for years. Well, reasonable people can disagree on this. Thanks for the discussion. The way I see it, the links in the article body are most often associated with some sort of context or description. The links in the "See also" section are most often not. [...] So, the rule prevents the section from becoming a list of indiscriminate items.

Even if this rule is lifted, I will continue removing those "See also" links that I had removed in the past, only this time I will cite WP:REPEATLINK. And there is a reason to it too: I have never removed a link from "See also" whose existence improved the article despite this "rule". MOS is a guideline and I treat it that way.

[...] If the restriction is lifted, then I don't see a natural limitation. In a biographical article that describes a person's associations with many other people over decades, all of them wikilinked, what would keep others from thinking "Hey, he worked with X, we should suggest to readers that they also see X", with the "see also" section ultimately containing dozens of links and thereby rendering the section fairly useless as a means of focus on especially related topics.

- It seems to me that those who (successfully) defended the guideline primarily see it as a way to avoid editorial discussions on what to include or exclude from a See also section. Moreover, some of them do not even intend to follow it when it is not in line with their editorial view, but want to keep it only because they like to use it when it is in line with their editorial view. But, as I see it, this rationale is in deep conflict with the spirit of Wikipedia, which favors discussion over the bureaucratic application of rules.

- For this reason, I believe that editorial judgment should be more important than the general rule, which mainly serves to prevent See also sections from becoming page-long lists of marginally related topics.

- Although we certainly want to avoid such overlong lists, the truth is that there are often good reasons to repeat a link in the See also section. One of them is that the See also section functions for many readers as a kind of further reading guide, helping them to choose which article to read next. From this perspective, it would not be logical to exclude the most closely related articles from the See also section. Yet precisely these articles have the highest chance of already having been cited before. This way, the See also section will absurdly point only to the least closely related articles. One may object that when there is a link in the article's body, readers will already have had the chance to click on it. But they may for various reasons not have clicked on it, and they will not in any case have all the relevant links clearly in mind anymore when they reach the end of the article so as to make the best informed choice. Some readers may also have started to read the article at some section that caught their interest in the table of contents, and have missed a number of relevant links in the other sections which they did not read.

- Because of reasons like these, links which are repeated in the See also section may often be very helpful, and they should only be removed when they are not. In the case of the repeated links you have removed from The Kybalion, I believe that As above, so below and Correspondence are highly relevant and worthy of repeating. Hermetica, on the other hand, has been mentioned already enough to not need repeating, and may be removed. As for the repeated links you have removed from Emerald Tablet, I believe that they are so extremely relevant that there is no good reason not to have them in the See also section.

- What do you think of this? ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 02:24, 2 August 2021 (UTC) (please remember to sign your posts with four tildes, ~~~~)

- A few things: 1. I don't think there is any contradiction or conflict between saying "the "See also" section should not repeat links that appear in the article's body." and "whether a link belongs in the "See also" section is ultimately a matter of editorial judgment". An article about topic X could have links to topics A and B in the body, and these should not be in the See Also section , but whether tangentially related topic C should be in the See Also section is a a matter of editorial judgment. For example, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1970_FIFA_World_Cup_Final can (and does) link to Pelé in the body, and should not link to it again in the See Also section, even though it is very important and very relevant to the article. But whether Brazil–Italy football rivalry belongs there is a matter of judgement. 2. You linked to a discussion about this very issue. Some people believed, like you, that the rule should be changed, but ultimately it was not, and the discussion ended with "There is strong consensus against the proposed change.". And it seems to me that what you are doing here is ignoring the result of the discussion. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Inf-in MD (talk • contribs) 12:50, 2 August 2021 (UTC)

- @Inf-in MD: thanks for engaging me on this! Yes, I am ignoring the result of the RfC, but I am following its spirit, which is that the rule serves the specific purpose of preventing See also sections from becoming overlong, that it should stay for that reason, but that it can be ignored outside of that context. Did you know that one of the five pillars of Wikipedia is that

Wikipedia has no firm rules

? It's a rule in itself here that "If a rule prevents you from improving or maintaining Wikipedia, ignore it." (see Wikipedia:Ignore all rules). You say that 1970 FIFA World Cup Final should not repeat the link to Pelé in the See also section, even though it's very important and relevant to the article. But regardless of rules, do you personally believe that the See also section of that article is better without a link to Pelé? This you should always do, to ask the one question: Does it make Wikipedia better or not? To quote:Answer that question first, then pick whatever policy, guideline, essay, or argument supports the answer. Don't flip the order. If you look at a policy page first, then decide that something is good/bad because that's the conclusion of the policy, you forgot to ask yourself the one question. And you could very well end up supporting an outcome which does not make Wikipedia better.

So I would like you to ask the one question with regard to the links in The Kybalion and Emerald Tablet. If you truly believe that Wikipedia is better without repeating them, then I won't argue over that. Thanks again for your attention! Sincerely, ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 18:12, 2 August 2021 (UTC)- I think Wikipedia:Ignore all rules is one of the worst things about wikipedia. Even if it did not create an internal paradox (can you use Wikipedia:Ignore all rules to ignore Wikipedia:Ignore all rules, thereby saying you can't ignore?), it is a potential source of endless arguments about whether a particular rule should be ignored, based on editors' subjective opinions. It is far better to fix rules if they create a problem. To me "See Also" sections are remnants of pre-internet paper encyclopedias, where the only way to draw attention to other relevant topics was via such footnotes. Hyperlinks fix that problem more elegantly. Ideally, there should be no "See Also" links, at all. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Inf-in MD (talk • contribs) 19:38, 2 August 2021 (UTC)

- Okay, though I do not agree with it, that's of course a perfectly respectable take on things. Thanks once more for engaging with me! ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 19:57, 2 August 2021 (UTC)

- Well, reasonable people can disagree on this. Thanks for the discussion and explaining your point of view. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Inf-in MD (talk • contribs) 14:37, 3 August 2021 (UTC)

- Okay, though I do not agree with it, that's of course a perfectly respectable take on things. Thanks once more for engaging with me! ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 19:57, 2 August 2021 (UTC)

- I think Wikipedia:Ignore all rules is one of the worst things about wikipedia. Even if it did not create an internal paradox (can you use Wikipedia:Ignore all rules to ignore Wikipedia:Ignore all rules, thereby saying you can't ignore?), it is a potential source of endless arguments about whether a particular rule should be ignored, based on editors' subjective opinions. It is far better to fix rules if they create a problem. To me "See Also" sections are remnants of pre-internet paper encyclopedias, where the only way to draw attention to other relevant topics was via such footnotes. Hyperlinks fix that problem more elegantly. Ideally, there should be no "See Also" links, at all. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Inf-in MD (talk • contribs) 19:38, 2 August 2021 (UTC)

- @Inf-in MD: thanks for engaging me on this! Yes, I am ignoring the result of the RfC, but I am following its spirit, which is that the rule serves the specific purpose of preventing See also sections from becoming overlong, that it should stay for that reason, but that it can be ignored outside of that context. Did you know that one of the five pillars of Wikipedia is that

- A few things: 1. I don't think there is any contradiction or conflict between saying "the "See also" section should not repeat links that appear in the article's body." and "whether a link belongs in the "See also" section is ultimately a matter of editorial judgment". An article about topic X could have links to topics A and B in the body, and these should not be in the See Also section , but whether tangentially related topic C should be in the See Also section is a a matter of editorial judgment. For example, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1970_FIFA_World_Cup_Final can (and does) link to Pelé in the body, and should not link to it again in the See Also section, even though it is very important and very relevant to the article. But whether Brazil–Italy football rivalry belongs there is a matter of judgement. 2. You linked to a discussion about this very issue. Some people believed, like you, that the rule should be changed, but ultimately it was not, and the discussion ended with "There is strong consensus against the proposed change.". And it seems to me that what you are doing here is ignoring the result of the discussion. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Inf-in MD (talk • contribs) 12:50, 2 August 2021 (UTC)

Thanks

I appreciate you spending time on Wikipedia:Articles for deletion/Hitchens's razor, my AN/I concern, and my talk page a while back when you helped me to understand policy better. You seem very professional and kind, and I appreciate that you have pointed out my mistakes in a professional and kind way. MarshallKe (talk) 13:13, 19 August 2021 (UTC)

- @MarshallKe: thank you for coming here and leaving me this very kind message. I appreciate it very much! Sincerely, ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 22:17, 19 August 2021 (UTC)

Another thank-you

I have long appreciated your good edits on a number of articles, so: thank you! You are careful and knowledgeable, you respect good scholarship, and you tactfully revert inappropriate edits. If you make changes to Pseudo-Democritus, please read Martelli first. I think his monograph on the subject concludes about as much as is reasonable to conclude from the available sources, and successfully dates this writer's work to ca. 60 AD. I know Martelli, and can vouch for his conscientious professional scholarship. Ajrocke (talk) 17:54, 27 August 2021 (UTC)

- Hello Ajrocke, thanks for the compliments!

I am indeed entirely basing my current rewrite of pseudo-Democritus on Martelli 2013. There is no doubt that he is the most important current expert on the topic, and the quality of his scholarship really speaks for itself. The article will still just be a stub, but I hope you'll like it!

I am indeed entirely basing my current rewrite of pseudo-Democritus on Martelli 2013. There is no doubt that he is the most important current expert on the topic, and the quality of his scholarship really speaks for itself. The article will still just be a stub, but I hope you'll like it!  ☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 18:05, 27 August 2021 (UTC)

☿ Apaugasma (talk ☉) 18:05, 27 August 2021 (UTC)

- Excellent re-write and expansion of the article pseudo-Democritus! Thanks for doing this.Ajrocke (talk) 16:55, 28 August 2021 (UTC)

Thank you very much!

Hi, Apaugasma! Thank you very much for your kindness for how to contribute to Wikipedia. It was the first edit of Wikipedia for me, and I seem to have made a mistake, editing it. If you made a correction for my edit, I thank you so much! I have some things to do now, and would like to read about Pneuma (Stoic) and Stoic Physics later. I will not discuss it on the talk pages. Take care!