Montgomery Clift

Montgomery Clift | |

|---|---|

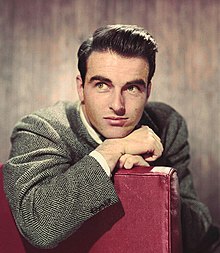

Studio publicity photograph, c. 1948 | |

| Born | Edward Montgomery Clift October 17, 1920 Omaha, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Died | July 23, 1966 (aged 45) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1935–1966 |

| Website | montgomeryclift |

Edward Montgomery Clift (/mɒntˈɡʌməri/; October 17, 1920 – July 23, 1966) was an American actor. A four-time Academy Award nominee, The New York Times said he was known for his portrayal of "moody, sensitive young men".[1][2]

He is best remembered for his roles in Howard Hawks's Red River (1948), William Wyler's The Heiress (1949), George Stevens's A Place in the Sun (1951), Alfred Hitchcock's I Confess (1953), Fred Zinnemann's From Here to Eternity (1953), Edward Dmytryk's The Young Lions (1958), Stanley Kramer's Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), and John Huston's The Misfits (1961).

Along with Marlon Brando and James Dean, Clift was one of the original method actors in Hollywood; he was one of the first actors to be invited to study in the Actors Studio with Lee Strasberg and Elia Kazan.[3] He also executed a rare move by not signing a contract after arriving in Hollywood, only doing so after his first two films were a success. This was described as "a power differential that would go on to structure the star–studio relationship for the next 40 years".[4] A documentary titled Making Montgomery Clift was made by his nephew in 2018, to clarify many myths that were created about the actor.[5]

Early life

Edward Montgomery Clift was born on October 17, 1920, in Omaha, Nebraska. His father, William Brooks "Bill" Clift (1886–1964), was the vice-president of Omaha National Trust Company.[6] His mother was Ethel Fogg "Sunny" Clift (née Anderson; 1888–1988). They had married in 1914.[7] Clift had a twin sister, Ethel, who survived him by 48 years, and a brother, William Brooks Clift, Jr. (1919–1986), who had an illegitimate son with actress Kim Stanley and was later married to political reporter Eleanor Clift.[8] Clift had English and Scottish ancestry. His mother was an adopted child who, at the age of 18, had been told that her birth parents were members of prominent American families who were forced to part by the tyrannical will of the girl's mother. She spent the rest of her life trying to gain the recognition of her alleged relations.

Part of Clift's mother's effort was her determination that her children should be brought up in the style of true aristocrats. Thus, as long as Clift's father was able to pay for it, he and his siblings were privately tutored, travelled extensively in America and Europe, became fluent in German and French, and led a protected life, sheltered from the destitution and communicable diseases which became legion following the First World War.[9] The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression of the 1930s ruined Clift's father financially. Unemployed and broke, he was forced to move his family to New York, but Clift's mother still persisted in her plans, and as her husband's situation improved, she was able to enroll Brooks at Harvard and Ethel at Bryn Mawr College. Clift, however, could not adjust to school, and never went to college. Instead, he took to stage acting, beginning in a summer production, which led to his debut on Broadway by 1935.[10]

In the next 10 years, Clift built a successful stage career working with, among others, Dame May Whitty, Alla Nazimova, Cornelia Otis Skinner, Fredric March, Tallulah Bankhead, Alfred Lunt, and Lynn Fontanne. He appeared in plays written by Moss Hart, Robert Sherwood, Lillian Hellman, Tennessee Williams, and Thornton Wilder, creating the part of Henry in the original production of The Skin of Our Teeth.[11] In 1939, as a member of the cast of the 1939 Broadway production of Noël Coward's Hay Fever, Clift participated in one of the first television broadcasts in the United States. A performance of Hay Fever was broadcast by NBC's New York television station W2XBS (the forerunner of WNBC) and was aired during the World's Fair as part of the introduction of television.[12] He resided in Jackson Heights, Queens, until he got his break on Broadway. Clift first acted on Broadway at age 15, when he appeared as Prince Peter in the Cole Porter musical Jubilee at the Imperial Theater. At 20, he appeared in the Broadway production of There Shall Be No Night, a work which won the 1941 Pulitzer Prize.

Clift did not serve during World War II, having been given 4-F status after suffering dysentery in 1942.

Career

Rise to stardom

At the age of 25, Clift moved to Hollywood. His first movie role was opposite John Wayne in the western Red River. Although filmed in 1946, the film was not released until August 1948. A critical and commercial success, the film was nominated for two Academy Awards.[13] His second movie was The Search, which premiered in the same year. Clift was unhappy with the quality of the script, and reworked it himself. The movie was awarded a screenwriting Academy Award for the credited writers.[14] Clift's naturalistic performance led to director Fred Zinnemann's being asked, "Where did you find a soldier who can act so well?", and he was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor. Clift signed on for his next movie, The Heiress (1949), in order to avoid being typecast. Clift was unhappy with the script, and unable to get along with most of the cast. He criticized co-star Olivia de Havilland, saying that she let the director shape her entire performance and telling friends that he wanted to change de Havilland's lines because "She isn't giving me enough to respond [to]". The studio marketed Clift as a sex symbol prior to the movie's release in 1949. Clift had a large female following, and Olivia de Havilland was flooded with angry fan letters because her character rejects Clift's character in the final scene of the movie. Clift ended up unhappy with his performance, and left early during the film's premiere. Clift also starred in The Big Lift (1950), which was shot on location in Germany.

Clift's performance in A Place in the Sun (1951) is regarded as one of his signature method acting performances. He worked extensively on his character, and was again nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor. For his character's scenes in jail, Clift spent a night in a real state prison. He also refused to go along with director George Stevens' suggestion that he do "something amazing" on his character's walk to the electric chair. Instead, he walked to his death with a natural, depressed facial expression. His main acting rival (and fellow Omaha native), Marlon Brando, was so moved by Clift's performance that he voted for Clift to win the Academy Award for Best Actor, and was sure that he would win. That year, Clift voted for Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire. A Place in the Sun was critically acclaimed; Charlie Chaplin called it "the greatest movie made about America". The film received added media attention due to the rumours that Clift and co-star Elizabeth Taylor were dating in real life. They were billed as "the most beautiful couple in Hollywood". Many critics still call Clift and Taylor "the most beautiful Hollywood movie couple of all time".[15] After a break, Clift committed himself to three more films, all of which premiered during 1953: I Confess, to be directed by Alfred Hitchcock; Vittorio De Sica's Terminal Station; and Fred Zinnemann's From Here to Eternity, which earned Clift his third Oscar nomination.

Clift was notoriously picky with his projects.[15] According to Taylor (as quoted in Patricia Bosworth's biography of Clift), "Monty could've been the biggest star in the world if he did more movies." Clift reportedly turned down the starring role in East of Eden, just as he had for Sunset Boulevard.[16]

Car crash

On the evening of May 12, 1956, while filming Raintree County, Clift was involved in a serious car crash when he apparently fell asleep while driving and smashed his car into a telephone pole, minutes after leaving a dinner party at the Beverly Hills home of his close friend and co-star, Elizabeth Taylor and her husband, Michael Wilding. Alerted by friend Kevin McCarthy, who witnessed the collision, Taylor raced to Clift's side, pulling a tooth out of his tongue as he had begun to choke on it. He suffered a broken jaw and nose, a fractured sinus, and several facial lacerations which required plastic surgery.[17] In a filmed interview years later in 1963, he described his injuries in detail, including how his broken nose could be snapped back into place.

After a two-month recovery, Clift returned to the set to finish the film. Despite the studio's concerns over profits, Clift correctly predicted the film would do well, if only because moviegoers would flock to see the difference in his facial appearance before and after the crash. Although the results of Clift's plastic surgeries were remarkable for the time, there were noticeable differences in his facial appearance, particularly the left side of his face, which was nearly immobile. The pain led him to rely on alcohol and pills for relief, as he had done after an earlier bout with dysentery left him with chronic intestinal problems. As a result, Clift's health and physical appearance deteriorated until his death.

Later career

Clift never fully physically or emotionally recovered from his car accident. His post-accident career has been referred to as the "longest suicide in Hollywood history" by acting teacher Robert Lewis because of Clift's subsequent abuse of painkillers and alcohol.[18] He began to behave erratically in public, which embarrassed his friends. Nevertheless, Clift continued to work over the next 10 years. His next three films were The Young Lions (1958), Lonelyhearts (1958), and Suddenly, Last Summer (1959). Clift next starred with Lee Remick in Elia Kazan's Wild River released in 1960. He played a Tennessee Valley Authority agent sent to do the impossible task of convincing Jo Van Fleet to leave her land, and ends up marrying her widowed granddaughter, played by Lee Remick. In 1958, Clift turned down what became Dean Martin's role as "Dude" in Rio Bravo, which would have reunited him with his co-stars from Red River, John Wayne and Walter Brennan, as well as with Howard Hawks, the director of both films.

Clift then co-starred in John Huston's The Misfits (1961), which was the final film of both Marilyn Monroe and Clark Gable. Monroe, who was also having emotional and substance abuse problems at the time, described Clift in a 1961 interview as "the only person I know who is in even worse shape than I am".

Clift's last nomination for an Academy Award was for Best Supporting Actor for his role in Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), a 12-minute supporting part. He played a developmentally disabled man who had been a victim of the Nazi sterilisation programme testifying at the Nuremberg trials. The film's director, Stanley Kramer, later wrote in his memoirs that Clift struggled to remember his lines even for this one scene, recalling that he told Clift "'Just turn to [Spencer] Tracy on the bench whenever you feel the need, and ad lib something. It will be all right because it will convey the confusion in your character's mind.' He seemed to calm down after this. He wasn't always close to the script, but whatever he said fitted in perfectly, and he came through with as good a performance as I had hoped."[19] In Robert Anderson Clift's 2018 documentary, it is revealed through superimposed pages of Clift's heavily annotated original script that the actor was not ad libbing and in fact deliberately and consciously performed much closer to his own rewritten dialogue than Kramer's account had suggested.[20]

By the time Clift was making John Huston's Freud: The Secret Passion (1962), his self-destructive lifestyle and behaviour were affecting his health. Universal Studios sued him for his frequent absences that caused the film to go over budget. The case was later settled out of court, but the damage to Clift's reputation as unreliable and troublesome endured. As a consequence, he was unable to find film work for four years. The film's success at the box office brought numerous awards for screenwriting and directing, but none for Clift himself. On January 13, 1963, a few weeks after the initial release of Freud, Clift appeared on the live TV discussion programme The Hy Gardner Show, where he spoke at length about the release of his current film, his film career, and treatment by the press. He also talked publicly for the first time about his 1956 car accident, the injuries he received, and its after-effects on his appearance. During the interview, Gardner jokingly mentioned that it is "the first and last appearance on a television interview programme for Montgomery Clift".

Barred from feature films, Clift turned to voice work. Early in his career, he had participated in radio broadcasts, though, according to one critic, he hated the medium.[21] On May 24, 1944, he was part of the cast of Eugene O'Neill's Ah, Wilderness! for The Theatre Guild on the Air.[22] In 1949, as part of the promotional campaign for the film The Heiress, he played Heathcliff in the one-hour version of Wuthering Heights for Ford Theatre.[23] In January 1951, he participated in the episode "The Metal in the Moon" for the series Cavalcade of America, sponsored by the chemical company DuPont Company. Also in 1951, Clift was for the first time cast as Tom in the radio world premiere of Tennessee Williams' The Glass Menagerie, with Helen Hayes (Amanda) and Karl Malden (the Gentleman Caller), for The Theatre Guild on the Air.[24] In 1964, he recorded for Caedmon Records The Glass Menagerie, with Jessica Tandy, Julie Harris, and David Wayne. In 1965, he gave voice to William Faulkner's writings in the TV documentary William Faulkner's Mississippi, which aired in April 1965.[25]

After four years of failed attempts to secure a film part, finally, in 1966, thanks to Elizabeth Taylor's efforts on his behalf, he was signed on to star in Reflections in a Golden Eye. In preparation for the shooting of this film, he accepted the role of James Bower in the French Cold War thriller The Defector, which was filmed in West Germany from February to April 1966. Clift died on July 23, 1966, before production on Reflections in a Golden Eye began.

Personal life

According to Clift's brother, Clift was either gay or bisexual.[26]

Elizabeth Taylor was a significant figure in his life. He met her when she was supposed to be his date at the premiere for The Heiress. They appeared together in A Place in the Sun, where, in their romantic scenes, they received considerable acclaim for their naturalness and their appearance. Clift and Taylor appeared together in two other films, Raintree County and Suddenly, Last Summer, and remained good friends until his death. In 2000, at the GLAAD Media Awards, where Taylor was honored for her work for the LGBT community, she made the first public declaration by anyone of the fact that Clift was gay and called him her closest friend and confidant.[27]

Because Clift was considered unemployable in the mid-1960s, Taylor put her salary for the film on the line as insurance, in order to have Clift cast as her co-star in Reflections in a Golden Eye.[15] Still, shooting kept being postponed, until Clift agreed to star in The Defector so as to prove himself fit for work. He insisted on performing his stunts himself, including swimming in the river Elbe in March. The schedule for Reflections in a Golden Eye was then set for August 1966, but Clift died before the movie was set to be shot. He was replaced by Marlon Brando.

Death

On July 22, 1966, Clift was in his New York City townhouse, located at 217 East 61st Street. He and his private nurse, Lorenzo James, had not spoken much all day. After midnight, shortly before 1:00 a.m. (01:00 ET), James went to his own bedroom to sleep, without saying another word to Clift. At 6:30 a.m. (06:30 ET), James woke up and went to wake Clift, but found the bedroom door closed and locked. Concerned and unable to break the door down, James ran down to the back garden and climbed up a ladder to enter through the second-floor bedroom window. Inside, he found Clift dead: he was undressed, lying in his bed still wearing his eyeglasses and with both fists clenched by his side. James then used the bedroom telephone to call the police and an ambulance.[citation needed]

Clift's body was taken to the city morgue about 2 miles (3.2 km) away at 520 First Avenue, and autopsied. The autopsy report cited the cause of death as a heart attack brought on by "occlusive coronary artery disease". No evidence was found that suggested foul play or suicide. It is commonly believed that drug addiction was responsible for Clift's many health problems and his death. In addition to lingering effects of dysentery and chronic colitis, an underactive thyroid was later revealed during the autopsy. The condition (among other things) lowers blood pressure; it could have caused Clift to appear drunk or drugged when he was sober.[29] Underactive thyroid also raise cholesterol, which might have contributed to his heart disease.[citation needed]

Following a 15-minute funeral at St. James' Church on Madison Avenue in Manhattan, which was attended by 150 guests, including Lauren Bacall, Frank Sinatra, and Nancy Walker, Clift was buried in the Friends Quaker Cemetery, Prospect Park, Brooklyn.[30] Elizabeth Taylor, who was in Rome, sent flowers, as did Roddy McDowall (who had recently co-starred with Clift in The Defector), Judy Garland, Myrna Loy, and Lew Wasserman.[citation needed]

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Role | Director | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | The Search | Ralph "Steve" Stevenson | Fred Zinnemann | |

| Red River | Matthew "Matt" Garth | Howard Hawks | ||

| 1949 | The Heiress | Morris Townsend | William Wyler | |

| 1950 | The Big Lift | Danny MacCullough | George Seaton | |

| 1951 | A Place in the Sun | George Eastman | George Stevens | |

| 1953 | I Confess | Fr. Michael William Logan | Alfred Hitchcock | |

| Terminal Station (aka Indiscretion of an American Wife) |

Giovanni Doria | Vittorio De Sica | ||

| From Here to Eternity | Robert E. Lee "Prew" Prewitt | Fred Zinnemann | ||

| 1957 | Raintree County | John Wickliff Shawnessy | Edward Dmytryk | |

| 1958 | The Young Lions | Noah Ackerman | Edward Dmytryk | |

| Lonelyhearts | Adam White | Vincent J. Donehue | ||

| 1959 | Suddenly, Last Summer | Dr. John Cukrowicz | Joseph L. Mankiewicz | |

| 1960 | Wild River | Chuck Glover | Elia Kazan | |

| 1961 | The Misfits | Perce Howland | John Huston | |

| Judgment at Nuremberg | Rudolph Petersen | Stanley Kramer | ||

| 1962 | Freud: The Secret Passion | Sigmund Freud | John Huston | |

| 1966 | The Defector | Prof. James Bower | Raoul Lévy | Posthumous release |

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | Hay Fever | Performer | Television Movie |

| 1963 | What's My Line? | Mystery Guest | Episode: Montgomery Clift |

| 1963 | The Merv Griffin Show | Self | Season 1 - Episode: 86 |

| 1965 | William Faulkner's Mississippi | Narrator | Television Documentary |

Theatre

| Year | Title | Role | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1933 | As Husbands Go | Performer | Sarasota, Florida |

| 1935 | Fly Away Home | Harmer Masters | 48th Street Theatre, Broadway |

| 1935 | Jubilee | Prince Peter | Imperial Theatre, Broadway |

| 1938 | Yr. Obedient Husband | Lord Finch | Broadhurst Theatre, Broadway |

| 1938 | Eye On the Sparrow | Philip Thomas | Vanderbilt Theatre, Broadway |

| 1938 | The Wind and the Rain | Charles Tritton | Millbrook Theatre, New York |

| 1938 | Dame Nature | Andre Brisac | Booth Theatre, Broadway |

| 1939 | The Mother | Tony | Lyceum Theatre, Broadway |

| 1940 | There Shall Be No Night | Erik Valkonen | Alvin Theatre, Broadway |

| 1941 | Out of the Frying Pan | Performer | Country Theater, Suffern |

| 1942 | Mexican Mural | Lalo Brito | Chain Auditorium, New York |

| 1942 | The Skin of Our Teeth | Henry | Plymouth Theatre, Broadway |

| 1944 | Our Town | George Gibbs | City Center, Broadway |

| 1944 | The Searching Wind | Samuel Hazen | Fulton Theatre, Broadway |

| 1945 | Foxhole in the Parlor | Dennis Patterson | Ethel Barrymore Theatre, Broadway |

| 1945 | You Touched Me | Hadrian | Booth Theatre, Broadway |

| 1954 | The Seagull | Constantin Treplev | Phoenix Theatre, Off-Broadway |

Radio

| Year | Programme | Episode | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | Theatre Guild on the Air | The Glass Menagerie | [31] |

Awards and nominations

| Year | Awards | Category | Project | Award | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | Academy Awards | Best Actor | The Search | Nominated | |

| 1951 | A Place in the Sun | Nominated | |||

| 1953 | From Here to Eternity | Nominated | |||

| 1961 | Best Supporting Actor | Judgment at Nuremberg | Nominated | ||

| 1961 | British Academy Film Awards | Best Foreign Actor | Nominated | ||

| 1961 | Golden Globe Awards | Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Nominated |

In 1960, Clift was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6104 Hollywood Boulevard.

Legacy

The song "The Right Profile" by the English punk rock band The Clash, from their album London Calling, is about the later life of Clift. The song alludes to his car crash and drug abuse, as well as the movies A Place in the Sun, Red River, From Here to Eternity, and The Misfits. "Monty Got a Raw Deal" by rock band R.E.M. is also about him. The song "Montgomery Clift" by British band Random Hold concerns the legend that Clift enjoyed hanging from the window ledges of tall buildings.

Clift was the subject of fascination by the character Vikar (James Franco) in the film Zeroville, which was shot in 2015 and released on September 20, 2019, in limited theaters, to largely negative reviews. The character has a tattoo of Mr. Clift and Elizabeth Taylor on his shaved head. James Franco's brother, Dave Franco, portrays Montgomery Clift in a short scene in the movie.

Clift (portrayed by Gavin Adams) was a major supporting character in the 2020 feature film As Long As I’m Famous, which explored his intimate relationship with a young Sidney Lumet during the summer of 1948.

See also

- List of actors with Academy Award nominations

- List of actors with two or more Academy Award nominations in acting categories

- List of LGBT Academy Award winners and nominees

Notes

- ^ Obituary Variety, July 27, 1966.

- ^ "Montgomery Clift Dead at 45; Nominated 3 Times for Oscar; Completed Last Movie, 'The Defector,' in June Actor Began Career at Age 13". The New York Times. July 24, 1966. p. 61.

- ^ Capua, p. 49

- ^ Petersen, Anne Helen (September 23, 2014). "Scandals of Classic Hollywood: The Long Suicide of Montgomery Clift". Vanity Fair.

- ^ Bridy, Tara (July 29, 2019). "Making Montgomery Clift: truth behind gay self-loathing myth". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ LaGuardia, p. 6

- ^ LaGuardia, p. 5

- ^ Krampner, Jon (2006). Female Brando: The Legend of Kim Stanley. New York: Back Stage Books. p. 78. ISBN 9780823088478.

- ^ Bosworth, chapters 1–4

- ^ Bosworth, chapter 6

- ^ Amy Lawrence, The Passion of Montgomery Clift, p. 13

- ^ Lawrence, p. 261

- ^ Red River (1948) - Awards

- ^ Awards Database – Montgomery Clift Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine January 2, 2016

- ^ a b c Bosworth, p. ??

- ^ Capua, p. 92

- ^ "Montgomery Clift Official Site". Cmgww.com. July 23, 1966. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Clarke, Gerald. "Books: Sunny Boy". Time Magazine February 20, 1978.

- ^ Kramer, et al., p. 193.

- ^ Clift, Robert and Demmon, Hillary (directors) (2018). Making Montgomery Clift (film). 1091 Pictures. Event occurs at 01:15:34.

- ^ Kass, Judith M. (1975). The Films of Montgomery Clift. Citadel Press. p. 34. ISBN 0806507179. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ Edoneill.com

- ^ Archive.org

- ^ Archive.org

- ^ Lawrence, chapter 7

- ^ Petersen, Anne Helen (September 23, 2014). "Scandals of Classic Hollywood: The Long Suicide of Montgomery Clift". Vanity Fair. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Kane, Matt (March 25, 2011). "Elizabeth Taylor at the 11th Annual GLAAD Media Awards". GLAAD. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ "Montgomery Clift's Pedigreed Upper East Side Townhouse Could Be Yours". Observer. September 9, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ^ McCann, p. 68

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 8764–8765). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Kirby, Walter (March 16, 1952). "Better Radio Programs for the Week". The Decatur Daily Review. p. 44. Retrieved May 23, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The 21st Academy Awards (1949) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences). Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ "The 24th Academy Awards (1952) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences). Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "The 26th Academy Awards (1954) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences). Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- ^ "The 34th Academy Awards (1962) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1962". BAFTA. 1962. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ "Montgomery Clift – Golden Globe Awards". HFPA. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

References

- Bosworth, Patricia (1978). Montgomery Clift: A Biography. Hal Leonard Corporation, 2007. N.B.: Also published in mass-market pbk. ed. (New York: Bantam Books, 1978); originally published by Harcourt, 1978. ISBN 0-87910-135-0 (H. Leonard), ISBN 0-553-12455-2 (Bantam)

- Capua, Michelangelo (2002). Montgomery Clift: A Biography. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1432-1

- Clift, Robert Anderson and Hillary Demmon (2018). Making Montgomery Clift. 1091 Pictures.

- Girelli, Elisabetta (2013) "Montgomery Clift Queer Star", Wayne University Press. ISBN 9780814335147

- Kramer, Stanley and Thomas M. Coffey (1997). A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World: A Life in Hollywood. ISBN 0-15-154958-3

- LaGuardia, Robert (1977). Monty: A Biography of Montgomery Clift. New York, Avon Books. ISBN 0-380-01887-X (paperback edition)

- Lawrence, Amy (2010) "The Passion of Montgomery Clift", Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press. ISBN 9780520260474

- McCann, Graham (1991). Rebel Males: Clift, Brando and Dean. H. Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-12884-8

External links

- Montgomery Clift at IMDb

- Montgomery Clift at the Internet Broadway Database

- Montgomery Clift at Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Montgomery Clift at the TCM Movie Database

- Montgomery Clift papers, 1933–1966, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Montgomery Clift papers, Additions, 1929–1969, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Screen Legends: Montgomery Clift, The Guardian

- Montgomery Clift: better than Brando, more tragic than Dean

- Montgomery Clift at Find a Grave

- 1920 births

- 1966 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- American male film actors

- American male stage actors

- American male radio actors

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- Burials in New York (state)

- LGBT actors from the United States

- LGBT male actors

- LGBT people from Nebraska

- Livingston family

- Male actors from Omaha, Nebraska

- Method actors

- People from Jackson Heights, Queens

- Twin people from the United States

- American Quakers

- Deaths from coronary artery disease

- 20th-century Quakers