Lilith

Lilith is a female Mesopotamian night demon or vampire associated with wind and thought to harm children. She is popular in neopagan veneration. The figure of Lilith first appeared in a class of wind and storm demons or spirits, as Lilitu, in Babylonia, circe 3000 B.C.E. Many scholars place the origin of the phonetic name "Lilith" at somewhere around 700 B.C.E.[1]

In the Book of Isaiah, Lilith (לִילִית, Standard Hebrew Lilith) is a kind of night-demon or animal, translated as onokentauros in the Septuagint, as lamia "witch" by Hieronymus of Cardia, and as screech owl in the King James Version of the Bible. Lilith also appears as a night demon in the Talmud and Midrash. She is often identified as the mother of all incubi and succubi. Late medieval Jewish legend portrays her as the first wife and equal of Adam. Considering Adam inferior, Lilith left the Garden of Eden of her own free will (Other stories claim Lilith refused to lie under Adam, as she considered that this was too submissive). Adam then bade three angels to find Lilith and bring her back. When Lilith refused, God punished her by commanding that she slay 100 of her children, called Lilin, each day. Lilith is also sometimes considered to be the paramour of Satan.[2]

Etymology

Hebrew לילית lilith, Akkadian līlītu are female Nisba adjectives from the Proto-Semitic root LYL "night", literally translating to nocturnal "female night being/demon". Sayce (Hibbert Lectures, 145ff.), Fossey (La Magie Assyrienne, 37ff.) and others reject an etymology based on the root LYL and suggest the origin of Līlīt was as a storm demon; this view is supported by the cuneiform inscriptions quoted by these scholars. Others find that Akkadian Lil-itu (=Lady Air) is a reference to the Sumerian Goddess Ninlil (also = Lady Air), Goddess of the South Wind and wife of Enlil. The story of Adapa, tells how Adapa broke the wings of the South Wind, for which he feared he would be punished with death. In ancient Iraq, the South Wind is associated with the onset of summer dust storms and general ill-health. The association with "night" may still be due to early popular etymology. The corresponding Akkadian masculine līlû shows no Nisba suffix and compares to Sumerian (kiskil-)lilla.

In Mesopotamian mythology

Kiskil-lilla

Lilith has been identified with ki-sikil-lil-la-ke4, a female being in the Sumerian prologue to the Gilgamesh epic, which may or may not be her or a predecessor. Some dispute identification with Lilith, because there is no basis for assuming this creature is Lilith, or even an Ardat Lili. It was translated as "Lilith", where the word for air is obviously present, there is no indication of a Lilith anymore than the presence of the word "ki" (Earth) indicates the Earth Goddess Ki.[3][4] Ki-sikil-lil-la-ke literally means maiden of Lila.

Kramer translates:

- a dragon had built its nest at the foot of the tree

- the Zu-bird was raising its young in the crown,

- and the demon Lilith had built her house in the middle.

- [...]

- Then the Zu-bird flew into the mountains with its young,

- while Lilith, petrified with fear, tore down her house and fled into the wilderness.[5]

Wolkenstein translates the same passage:

- a serpent who could not be charmed made its nest in the roots of the tree,

- The Anzu bird set his young in the branches of the tree,

- And the dark maid Lilith built her home in the trunk.[5]

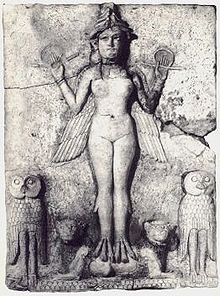

The Burney relief

The Gilgamesh passage quoted above has in turn been applied by some to the Burney relief (Norman Colville collection), which dates to roughly 1950 BC and is a sculpture of a woman who has bird talons and is flanked by owls.

The key to this identification lies in the bird talons and the owls. While the relief may depict the demon Kisikil-lilla-ke of the Gilgamesh passage or a goddess, identification with Lilitu is more tenuous and likely influenced by the "screech owl" translation of the KJV. Most scholars accept it to actually be Inanna or her underworld sister Ereshkigal. However, the real identity of this figure remains inconclusive. A very similar relief dating to roughly the same period is preserved in the Louvre (AO 6501).

Mesopotamian Lilitu

In early references to Lilitu in Mesopotamia, she appears not as a singular, central figure, but as an entire class of wind and storm spirits, around 3000 BCE. Associated with the destructive powers of nature, they were thought to bring disease, illness, death, violent storms, and night terrors (Hurwitz 81-83).

Three figures are closely related in Babylonian mythology: Lilu, a male demon, and Lilitu and Ardat Lili, both females. Lilitu evolved to became known as Lilith in Isaiah 34:14, thought[6] to be inherited during the Babylonian occupation of Israel.

A similar related Mesopotamian demon, Lamashtu, also contributed to the evolution of the Lilitu myth. Lamashtu was a demon thought to harm children and women during childbirth. This demon was described as having bird talons for feet, having a lioness head and is often depicted as a fearsome creature with wild animals. In further fashion of Lilith, she also had statues, amulets, and incantations against her.

The "Lilith Prophylactic" of Arslan Tash (Aleppo National Museum) is a suspected forgery, but if genuine it would be a 7th century BC plaque featuring a sphinx-like creature and a she-wolf devouring a child, with a Phoenician inscription addressing the sphinx creature as Lili.[citation needed]

Related myths

A figure often compared to Lilith is the Greek Lamia. Said to be a daughter of the goddess Hecate or turned into a monster by the jealous Hera, she has a cannibalistic appetite for children, and is often blamed for kidnapping them. Lamia has a role akin to Lilith in that, she too, is said to have a powerful, dangerous, sexual appetite for men.[7][8]

Lamia is described as appearing from the torso up as a woman and serpentine from the torso down. She presides over vampiric, blood-sucking Lamiai, (similar to succubi in Medieval myths) and is said to give birth to the horrible demoness Empusae, a creature compared to lilim.

Lilith in the Bible

Isaiah 34:14, describing the desolation of Edom, is the only occurrence of Lilith in the Hebrew Bible:

- Hebrew (ISO 259): Template:Semxlit

- morpho-syntactic analysis: "yelpers meet-[perfect] howlers; hairy-ones cry-[imperfect] to fellow. liyliyth reposes-[perfect], acquires-[perfect] resting-place."

- KJV: "The wild beasts of the desert shall also meet with the wild beasts of the island, and the satyr shall cry to his fellow; the screech owl also shall rest there, and find for herself a place of rest."

Schrader (Jahrbuch für Protestantische Theologie, 1. 128) and Levy (ZDMG 9. 470, 484) suggest that Lilith was a goddess of the night, known also by the Jewish exiles in Babylon. Evidence for Lilith being a goddess rather than a demon is lacking. Isaiah dates to the 6th century BC, and the presence of Jews in Babylon would coincide with the attested references to the Līlītu in Babylonian demonology.

The Septuagint translates onokentauros, apparently for lack of a better word, since also the Template:Semxlit "satyrs" earlier in the verse are translated with daimon onokentauros. The "wild beasts of the island and the desert" are omitted altogether, and the "crying to his fellow" is also done by the daimon onokentauros.

In Horace (De Arte Poetica liber, 340), Hieronymus of Cardia translated Lilith as Lamia, a witch who steals children, similar to the Breton Korrigan, in Greek mythology described as a Libyan queen who mated with Zeus. After Zeus abandoned Lamia, Hera stole Lamia's children, and Lamia took revenge by stealing other women's children.

The screech owl translation of the KJV is without precedent, and apparently together with the "owl" (yanšup, probably a water bird) in 34:11, and the "great owl" (qippoz, properly a snake,) of 34:15 an attempt to render the eerie atmosphere of the passage by choosing suitable animals for difficult to translate Hebrew words. It should be noted that this particular species of owl is associated with the vampiric Strix of Roman legend.[citation needed]

Later translations include:

- night-owl (Young, 1898)

- night monster (ASV 1901, NASB 1995)

- night hag (RSV 1947)

- night creature (NIV 1978, NKJV 1982, NLT 1996)

- nightjar (New World Translation, 1984)

- vampires (Moffatt Translation, 1922).

Jewish tradition

A Hebrew tradition exists in which an amulet is inscribed with the names of three angels (Senoy, Sansenoy, and Semangelof) and placed around the neck of newborn boys in order to protect them from the lilin until their circumcision. There is also a Hebrew tradition to wait three years before a boy's hair is cut so as to attempt to trick Lilith into thinking the child is a girl so that the boy's life may be spared.[citation needed]

Dead Sea scrolls

The appearance of Lilith in the Dead Sea Scrolls is somewhat more contentious, with one indisputable reference in the Song for a Sage (4Q510-511), and a promising additional allusion found by A. Baumgarten in The Seductress (4Q184). The first and irrefutable Lilith reference in the Song occurs in 4Q510, fragment 1:

"And I, the Instructor, proclaim His glorious splendor so as to frighten and to te[rrify] all the spirits of the destroying angels, spirits of the bastards, demons, Lilith, howlers, and [desert dwellers…] and those which fall upon men without warning to lead them astray from a spirit of understanding and to make their heart and their […] desolate during the present dominion of wickedness and predetermined time of humiliations for the sons of lig[ht], by the guilt of the ages of [those] smitten by iniquity – not for eternal destruction, [bu]t for an era of humiliation for transgression."

Akin to Isaiah 34:14, this liturgical text both cautions against the presence of supernatural malevolence and assumes familiarity with Lilith; distinct from the biblical text, however, this passage does not function under any socio-political agenda, but instead serves in the same capacity as An Exorcism (4Q560) and Songs to Disperse Demons (11Q11) insomuch that it comprises incantations – comparable to the Arslan Tash relief examined above – used to "help protect the faithful against the power of these spirits." The text is thus, to a community "deeply involved in the realm of demonology," an exorcism hymn.[citation needed]

Another text discovered at Qumran, conventionally associated with the Book of Proverbs, credibly also appropriates the Lilith tradition in its description of a precarious, winsome woman – The Seductress (4Q184). The ancient poem – dated to the first century BCE but plausibly much older – describes a dangerous woman and consequently warns against encounters with her. Customarily, the woman depicted in this text is equated to the "strange woman" of Proverbs 2 and 5,[citation needed] and for good reason; the parallels are instantly recognizable:

"Her house sinks down to death,

And her course leads to the shades. All who go to her cannot return And find again the paths of life."

(Proverbs 2:18-19)

"Her gates are gates of death,

and from the entrance of the house she sets out towards Sheol. None of those who enter there will ever return, and all who possess her will descend to the Pit."

(4Q184)

However, what this association does not take into account are additional descriptions of the "Seductress" from Qumran that cannot be found attributed to the "strange woman" of Proverbs; namely, her horns and her wings: "a multitude of sins is in her wings." The woman illustrated in Proverbs is without question a prostitute, or at the very least the representation of one, and the sort of individual with whom that text’s community would have been familiar. The "Seductress" of the Qumran text, conversely, could not possibly have represented an existent social threat given the constraints of this particular ascetic community. Instead, the Qumran text utilizes the imagery of Proverbs to explicate a much broader, supernatural threat – the threat of the demoness Lilith.[citation needed]

Talmud

Although the Talmudic references to Lilith are sparse, these passages provide the most comprehensive insight into the demoness yet seen in Judaic literature which both echo Lilith’s Mesopotamian origins and prefigure her future as the perceived exegetical enigma of the Genesis account. Recalling the Lilith we have seen, Talmudic allusions to Lilith illustrate her essential wings and long hair, dating back to her earliest extant mention in Gilgamesh:

"Rab Judah citing Samuel ruled: If an abortion had the likeness of Lilith its mother is unclean by reason of the birth, for it is a child but it has wings." (Niddah 24b)

"[Expounding upon the curses of womanhood] In a Baraitha it was taught: She grows long hair like Lilith, sits when making water like a beast, and serves as a bolster for her husband." (‘Erubin 100b)

More unique to the Talmud with regard to Lilith is her insalubrious carnality, alluded to in The Seductress but expanded upon here sans unspecific metaphors as the demoness assuming the form of a woman in order to sexually take men by force while they sleep:

"R. Hanina said: One may not sleep in a house alone [in a lonely house], and whoever sleeps in a house alone is seized by Lilith." (Shabbath 151b)

Yet the most innovative perception of Lilith offered by the Talmud appears earlier in ‘Erubin, and is more than likely inadvertently responsible for the fate of the Lilith myth for centuries to come:

"R. Jeremiah b. Eleazar further stated: In all those years [130 years after his expulsion from the Garden of Eden] during which Adam was under the ban he begot ghosts and male demons and female demons [or night demons], for it is said in Scripture, And Adam lived a hundred and thirty years and begot a son in own likeness, after his own image, from which it follows that until that time he did not beget after his own image…When he saw that through him death was ordained as punishment he spent a hundred and thirty years in fasting, severed connection with his wife for a hundred and thirty years, and wore clothes of fig on his body for a hundred and thirty years. – That statement [of R. Jeremiah] was made in reference to the semen which he emitted accidentally." (‘Erubin 18b)

Comparing ‘Erubin 18b and Shabbath 151b with the later passage from the Zohar: “She wanders about a night night, vexing the sons of men and causing them to defiles themselves (19b),” it appears clear that this Talmudic passage indicates such an averse union between Adam and Lilith.

Shedim Cults

A cult in Mesopotamia is said to be related to Lilith by early Jewish leaders. Shedim is plural for "spirit" or "demon". Figures that represent shedim are the shedu of Babylonian mythology. These figures were depicted as anthropomorphic, winged bulls, associated with wind. They were thought to guard palaces, cities, houses and temples. In magical texts of that era they could either be malevolent or benelovent.[9] The cult was said to include human sacrifice as part of practice.

Shedim in Jewish thought and literature were portrayed as quite malevolent. Some writings contend that they are storm-demons. Thier creation is presented in 3 contradicting Jewish tales, one is that during creation God created the shedim but did not create their bodies and forgot them on the Sabbath when he rested, the 2nd is that they are descendants of demons in the form of serpents, and the last states that they are simply descendants of Adam & Lilith. Another story asserts that after the tower of Babel, some people were scattered and became Shedim, Ruchin, and Lilin.

Kabbalah

In Kabbalah she appears as the Seductress in many passages, often considered a wife of Samael, and is said to have at one time been born as one with him, in the image of Adam and Eve. Interestingly, a passage in the 13th century called the Treatise on the Left Emanation explains that there are two "Liliths". The Lesser being married to the great demon Asmodeus.

- In answer to your question concerning Lilith, I shall explain to you the essence of the matter. Concerning this point there is a received tradition from the ancient Sages who made use of the Secret Knowledge of the Lesser Palaces, which is the manipulation of demons and a ladder by which one ascends to the prophetic levels. In this tradition it is made clear that Samael and Lilith were born as one, similar to the form of Adam and Eve who were also born as one, reflecting what is above. This is the account of Lilith which was received by the Sages in the Secret Knowledge of the Palaces. The Matron Lilith is the mate of Samael. Both of them were born at the same hour in the image of Adam and Eve, intertwined in each other. Asmodeus the great king of the demons has as a mate the Lesser (younger) Lilith, daughter of the king whose name is Qafsefoni. The name of his mate is Mehetabel daughter of Matred, and their daughter is Lilith.[10][11]

Another passage charges Lilith as being a tempting serpent of Eve's:

- And the Serpent, the Woman of Harlotry, incited and seduced Eve through the husks of Light which in itself is holiness. And the Serpent seduced Holy Eve, and enough said for him who understands. An all this ruination came about because Adam the first man coupled with Eve while she was in her menstrual impurity -- this is the filth and the impure seed of the Serpent who mounted Eve before Adam mounted her. Behold, here it is before you: because of the sins of Adam the first man all the things mentioned came into being. For Evil Lilith, when she saw the greatness of his corruption, became strong in her husks, and came to Adam against his will, and became hot from him and bore him many demons and spirits and Lilin. (Patai81:455f)

This may relate to various medieval iconagraphy of Lilith tempting Adam and Eve.[12]

The prophet Elijah is said to have confronted Lilith in one text. In this encounter she had come to feast on the flesh of the mother, with a host of demons, and take the new born from her. She eventually reveals her secret names to Elijah in the conclusion. These names are said to cause Lilith to lose her power: lilith, abitu, abizu, hakash, avers hikpodu, ayalu, matrota...[13]

In others, probably informed by The Alphabet of Ben-Sira, she is Adam's first wife. (Yalqut Reubeni, Zohar 1:34b, 3:19[14])

Lilith as Qliphoth

Lilith is listed as one of the Qliphoth, corresponding to the Sephirah Malkuth in the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. The demon Lilith, the evil woman, is described as a beautiful woman, who transforms into a black, monkey-like demon, and it is associated with the power of seduction.

The Qliphoth is the unbalanced power of a sephirah. Malkuth is the lowest sephirah, the realm of the earth, into which all the divine energy flows, and in which the divine plan is worked out. However, its unbalanced form as Lilith, the seductress, is obvious. The material world, and all of its pleasures, is the ultimate seductress, and can lead to materialism unbalanced by the spirituality of the higher spheres. This ultimately leads to a descent into animal consciousness. The balance must therefore be found between Malkuth and Kether, to find order and harmony, without giving into Lilith, materialism, or Thaumiel, Satan, spiritual pride and egotism.

Lilith as Adam's first wife

A medieval reference to Lilith as the first wife of Adam is the anonymous The Alphabet of Ben-Sira, written sometime between the 8th and 11th centuries.

Genesis 2:18: After God created Adam, who was alone, He said, 'It is not good for man to be alone.' He then created a woman for Adam, from the earth, as He had created Adam himself, and called her Lilith. Adam and Lilith immediately began to fight. She said, 'I will not lie below,' and he said, 'I will not lie beneath you, but only on top. For you are fit only to be in the bottom position, while I am to be the superior one.' Lilith responded, 'We are equal to each other inasmuch as we were both created from the earth.' But they would not listen to one another. When Lilith saw this, she pronounced the Ineffable Name and flew away into the air. (In this act, Lilith becomes unique in that she is not touched by "original sin", having left the garden before Eve came into existence. Lilith also reveals herself to be powerful in her own right by knowing the name of God).

Adam stood in prayer before his Creator: 'Sovereign of the universe!' he said, 'the woman you gave me has run away.' At once, the Holy One, blessed be He, sent these three angels Senoy, Sansenoy, and Semangelof, to bring her back. "Said the Holy One to Adam, 'If she agrees to come back, what is made is good. If not, she must permit one hundred of her children to die every day.' The angels left God and pursued Lilith, whom they overtook in the midst of the sea, in the mighty waters wherein the Egyptians were destined to drown. They told her God's word, but she did not wish to return. The angels said, 'We shall drown you in the sea.'

"'Leave me!' she said. 'I was created only to cause sickness to infants. If the infant is male, I have dominion over him for eight days after his birth, and if female, for twenty days.' "When the angels heard Lilith's words, they insisted she go back. But she swore to them by the name of the living and eternal God: 'Whenever I see you or your names or your forms in an amulet, I will have no power over that infant.' She also agreed to have one hundred of her children die every day. Accordingly, every day one hundred demons perish, and for the same reason, we write the angels names on the amulets of young children. When Lilith sees their names, she remembers her oath, and the child recovers."

Lilith then went on to mate with Samael and various other demons she found beside the Red Sea, creating countless lilin.

The background and purpose of The Alphabet of Ben-Sira is unclear. It is a collection of stories about heroes of the Bible and Talmud, it may have been a collection of folk-tales, a refutation of Christian, Karaite, or other separatist movements; its content seems so offensive to contemporary Jews that it was even suggested that it could be an anti-Jewish satire,[15] although, in any case, the text was accepted by the Jewish mystics of medieval Germany.

The Alphabet of Ben-Sira is the earliest surviving source of the story, and the conception that Lilith was Adam's first wife became only widely known with the 17th century Lexicon Talmudicum of Johannes Buxtorf.

Lilith in the Romantic Period

During the English Romantic period (1789 - 1832) Lilith's image began to change dramatically.[16] Goethe and Keats are two early Romantic authors that were credited to being the first to be influential in the shifting of the image of Lilith and to bring her legend into a larger, more, mainstream audience.[17] Later, during the Pre-Raphaelites period, Dante Gabriel Rossetti was famously responsible for bringing a new interpetation of Lilith's identity, image, and myth, where she was adapted by feminists as a modern heroine.[16] A primary consideration for Romantics was the favoring of innovation against traditional forms and styles.

Lilith in Faust

In the earliest Romantic work --Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's 1808 work, Faust Part I-- Lilith makes another literary appearance, one that has been seen in nearly 600 years since the Zohar. This appearance is quite significant when compared to previous more ancient works, Lilith begins to take on a new dimension and a more positive role.

The legends about Dr. Faustus may have begun about 1540. In most versions are his quests for forbidden and often hidden knowledge. During a "Walpurgis" Night scene of Faust by Goathe, Lilith makes one appearance:

- FAUST:

- Who's that there?

- MEPHISTOPHELES:

- Take a good look.

- Lilith.

- FAUST.

- Lilith? Who is that?

- MEPHISTOPHELES.

- Adam's wife, his first. Beware of her.

- Her beauty's one boast is her dangerous hair.

- When Lilith winds it tight around young men

- She doesn't soon let go of them again.

(1992 Greenberg translation, lines 4206-4211)

With her "ensnaring" sexuality, Goethe draws upon ancient legends of Lilith which associate her with Adam. Perhaps, more importantly, is the identifying marker of Lilith, her long, ensnaring hair, a image recounted in more familer ancient tales. This image is the first "modern" literary mention of Lilith and continues to dominate throughout the nineteenth century.

After Mephistopheles offers this warning to Faust, he then, quite ironically, encourages Faust to dance with "the Pretty Witch". Lilith and Faust engage in a short conversation, where Lilith recounts the days spent in Eden.

- FAUST. [Dancing with the young witch]

- A lovely dream I dreamt one day

- I saw a green-leaved apple tree,

- Two apples swayed upon a stem,

- So tempting! I climbed up for them.

- THE PRETTY WITCH.

- Ever since the days of Eden

- Apples have been man's desire.

- How overjoyed I am to think, sir,

- Apples grow, too, in my garden.

(1992 Greenberg translation, lines 4216- 4223)

Here, Goethe, chooses to elaborate on the Eden scene, focusing on the popular Lilith's identity as the first wife of Adam rather than a child-killing and disease-bearing spirit or demon.

This brief mention is important, as it marks Lilith's debut in modern literature. Additionally, her character for the most part is unnecessary, this establishes that Goethe's intentions and reason in invoking her image and associations may differ.[18] It, also, suggests familiarity with the figure of Lilith. This text heavily influenced the later Romantic art and literature of Lilith and how she is often potrayed and continues to dominate representations throughout the 19th century.[18]

Keats, Lilith, and "Lamia"

In Keats's poem: "Lamia" (1819), the two tales of Lamia and Lilith begin to assimilate and forge a connection.

The title female charcter is never referred to as Lilith, but the similarities between the two are too prominent to be overlooked. A enchantress and she-demon, Lamia is the archetypal Romantic representation of what Lilith will become.[19] She is never branded as "immoral" or "evil" by Keats. The reader is invited to feel Lamia's pain under her unfortunate circumstances. This sparks the beginning of the tranformation of Lilith and Lamia. While both are associated with wickedness, these inherently negative aspects are redefined in a way to make it look unimportant.[19]

The poem begins with Lamia stuck in a serpent's body. It never states how she became that way, but the poem hints that she had a previous human existence. She appeals to Hermes: I was a woman, let me have once more / A woman's shape, and charming as before. / I love a youth of Corinth - O the bliss! / Give me my woman's form, and place me where he is" (I.117-120). The poem continues with Lamia's falling in love with a traveler named Menippus Lycius (whose name is a epithet of the god Apollo.[20])

"Lamia" introduces the dual sexual nature of Lilith: virgin but also seductress. The paradox is first introduced in these lines: "A virgin purest lipp'd, yet in the lore / Of love deep learned to the red heart's core" (I.189-190). This contradiction is also present in founding texts, some of which that claim Lilith gives birth to children in the hundreds each day, while she, likewise, murders hundreds of children.[19]

The most important aspect of Keats's Lilith-themed poem is that of the her association with excess. Her words are spoken as if "through bubbling honey," her song is "too sweet," and she herself is described as "bitter-sweet" (I.64, 299, 59). Within the poem, Lycius himself is driven to comment on this excess, professing that Lamia's mere presence invokes "a hundred thirsts." Lycius further proclaims that he will die without Lamia and that her memory alone is enough to kill (ln. 269-270).

The characterization of Lamia bears great similarities to the figure of Lilith; many other facets are omitted on purpose, such as the night terror aspect. Although she remains a seductress, her intentions are not considered immoral or are condemned. As the Norton Anthology introduction to the poem states: "Lamia is an enchantress, a liar, and a calculating expert in amour; but she apparently intends no harm, is genuinely in love, and is very beautiful" (797).[19]

Goethe simply ignores her negative aspects, Keats altogether rewrites Lilith's original identity. Even the serpent, a symbol in popular Western lore denoted with evil and a cult animal of Lilith's, is shed in the body of the poem. From this "evil" evolves a beautiful and sensuous womanly figure. Many scholars of Romantic literature further associate the unamed figure in another Keats poem, "La Belle Dame Sans Merci", to that of Lilith. Akin to Lamia, the figure of the poem is a beautiful seductress associated with death.[21]

Pre-Raphaelite

After Keats's poem "La Belle Dame Sans Merci" about an unnamed seductress figure, there exist about a 40-year gap of art and literature concerning the figure of Lilith. About 1848 a brotherhood develops, the Pre- Raphaelite Brotherhood.[22] Goethe and Keats's work on the subject was a major influence on the brotherhood and its adoption of the theme of Lilith. The adoption of this theme led to mainstream recognition and acceptance (rather positive or negative) of legends of Lilith and her counterparts.[22]

However, it is Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Pre- Raphaelite Brotherhood work that serves as the basis for many modern conceptions and interpretations and the shifting of attitudes concerning the subject.[23][16] Rossetti in 1863 began painting what would be his first rendition of "Lady Lilith", a painting he expected to be the "best picture hitherto" (Rossetti, W.M., ed. 188).[24] The woman of the painting is certainly the post-biblical Lilith, however the title "Lady" denotes that he wanted the audience to focus on attributes of sensuality and the outset of womanhood. Symbols appear concerning the infamous "femme fatale" look in the painting, poppies (death) and cold; white roses (sterile passion) suggest her feminity while symbolizing her seductive and death qualities.[24]

Accompanying his "Lady Lilith" painting from 1863, he wrote a sonnet entitled "Lilith", which was first published in Swinburne's pamphlet-review (1868), "Notes on the Royal Academy Exhibition". The poem and the picture appeared together alongside Rossetti's painting "Sibylla Palmifera" and the sonnet "Soul's Beauty". In 1881, the Lilith sonnet was renamed "Body's Beauty" in order to highlight the contrast between it and "Soul's Beauty," and the two were placed sequentially in "The House of Life" (sonnets number 77 and 78).[25]

The sonnet "Lilith" or "Body's Beauty":

- Of Adam's first wife, Lilith, it is told

- (The witch he loved before the gift of Eve,)

- That, ere the snake's, her sweet tongue could deceive,

- And her enchanted hair was the first gold.

- And still she sits, young while the earth is old,

- And, subtly of herself contemplative,

- Draws men to watch the bright web she can weave,

- Till heart and body and life are in its hold.

- The rose and poppy are her flower; for where

- Is he not found, O Lilith, whom shed scent

- And soft-shed kisses and soft sleep shall snare?

- Lo! as that youth's eyes burned at thine, so went

- Thy spell through him, and left his straight neck bent

- And round his heart one strangling golden hair.

- (Collected Works, 216)

Rossetti himself was aware that this modern view was in complete contrast to her Jewish lore; he wrote in 1870:

"Lady [Lilith]... represents a Modern Lilith combing out her abundant golden hair and gazing on herself in the glass with that self-absorption by whose strange fascination such natures draw others within their own circle." (Rossetti, W. M. ii.850, D.G. Rossetti's emphasis)[24]

These highly influential Romantic authors and their views usurp Lilith's original child-killing and disease-bearing attributes that incited fear. Instead, they focus on the on her sensualized, immortal, often seductive aspects, and her beauty as unobtainable desire.[26][27][22]

Browning's Adam, Lilith, and Eve

Robert Browning, a Victorian poet, re-envisioned Lilith in his poem "Adam, Lilith, and Eve". First published in 1883, the poem uses the traditional myths surrounding the triad of Adam, Eve, and Lilith.

He depicts Lilith and Eve as being friendly and complicitous to each other, as the sit together on either side of Adam. Under the threat of death, Eve admits that she never loved Adam, while Lilith confesses that she always loved him:

- "As the worst of the venom left my lips,

- I thought, 'If, despite this lie, he strips

- The mask from my soul with a kiss -- I crawl

- His slave, -- soul, body, and all!"

- (Browning 1098)

Adam laughs off at the notions of both Lilith's and Eve's. Browning's poem shows Lilith's charcter to be devoid of the once negative aspects she once possessed, other than a motiveless duplicity. Browning chooses to focus on her emotional attibutes, rather than that of her ancient demon predecessors.[28] Such contemporary representations of Lilith continue to be popular among modern Pagans and feminists alike.[29][30]

The Modern Lilith

Ceremonial Magick

Few magickal orders exist dedicated to the undercurrent of Lilith and deal in initiations specifically related to the Aracana of the first Mother. Two reputable organizations that progressively use initiations and magick associated with Lilith are the Ordo Antichristianus Illuminati and the Order of Phosphorus (see excerpt below). Author Joshua Seraphim has written three texts associated with the egregore of Lilith entitled "Rite of Lilith," "Confessionis ex Lilitu," and the "Lamentations of Lilith."

Lilith appears as a succubus in Aleister Crowley's De Arte Magica. Lilith was also one of the middle names of Crowley’s first child, Ma Ahathoor Hecate Sappho Jezebel Lilith Crowley (b. 1904, d.1906). She is sometimes identified with Babalon in Thelemic writings.

A Thelemic rite, based on an earlier German rite, offers the invocation of Lilith.[31][32]

"Dark is she, but brilliant! Black are her wings, black on black! Her lips are red as rose, kissing all of the Universe! She is Lilith, who leadeth forth the hordes of the Abyss, and leadeth man to liberation! She is the irresistible fulfiller of all lust, seer of desire. First of all women was she - Lilith, not Eve was the first! Her hand brings forth the revolution of the Will and true freedom of the mind! She is KI-SI-KIL-LIL-LA-KE, Queen of the Magic! Look on her in lust and despair!" (Lilith Ritus, from the German by Joseph Max)

A 2006 occult work by ceremonial magickian Donald Tyson, titled Liber Lilith details the secret cosmology for the 'Mother of Harlots' and spawn of all nightbreed monsters Lilith. The book proclaims itself as saved from the ashes of Dr Dee's library at Mortlake in the 1580's.[33]

Modern Luciferianism

In modern Luciferianism, Lilith is considered a consort and/or an aspect of Lucifer and is identified with the figure of Babalon. She is said to come from the mud and dust, and is known as the Queen of the Succubi. When she and Lucifer mate, they form an androgynous being called "Baphomet" or the "Goat of Mendes," also known in Luciferianism as the "God of Witches."[34][35]

The writings by Micheal Ford,The Foundations of the Luciferian Path, contends that Lilith forms the "Luciferian Trinity", composed of her, Samael and Cain. Likewise, she is said to have been Cain's actual mother, as opposed to Eve, but through her. Lilith here is seen as a goddess of witches, the dark feminine principle, and is also known as the goddess Hecate.[36]

Neo-Paganism

Many early writers that contributed to modern day Wicca/Witchcraft and Neo-Paganism expressed special reverence for Lilith. Charles Leland denoted Aradia with Lilith:

"Aradia, says Leland, is Herodias, who was regarded very early on in stregoneria folklore as being associated with Diana as chief of the witches...Leland further notes that Herodias is a name that comes from West Asia, where it denoted an early form of Lilith."[37][38]

Gerald Gardner asserted that there was continuous historical worship of Lilith to present day, and that her name is sometimes given to the goddess being personified in the coven, by the priestess. This idea was further attested by Doreen Valiente, who cited her as a presiding goddess of the Craft: “the personification of erotic dreams, the suppressed desire for delights”.[39]

In this contemporary concept, Lilith is viewed as the embodiment of the goddess, a designation that is thought to be shared with what are said to be her counterparts: Inanna, Ishtar, Asherah, Anath and Isis.[40]

Modern pagans sometimes equate Lilith with the Vodun loa Erzulie.[citation needed]

Astrological Lilith

In modern Western astrology, "Lilith" is a name given to three distinct phenomena. The first one of these is a main-belt asteroid, 1181 Lilith. It was discovered by Russian-French astronomer Benjamin Jekhowsky in 1927 and given the provisional designation 1927CQ.

The asteroid Lilith has a period of 4.36, it is thought to designate "conflict resolution... divided loyalties; favoritism; issues of personal and sexual power, domination...and violence; doubts over the integrity or loyalty of partners; female sexual assertiveness, fantasies, independence and lust; a lack of sexual commitment; love triangles; manipulative relationship behaviour; a non-submissive disposition, particularly with regard to gender roles for women; negotiation and compromise ability; repressed anger (sometimes leading to vindictive behaviour); personal independence; resentment arising from rejection; rivalry for affection, commitment or fidelity; sexual expectations or criticism; subterfuge in relationships; an uncompromising stance over beliefs; and the use of sex as a weapon of vengeance or domination."[41]

The second is the "Dark Moon" Lilith. It is not an actual phase of the moon, but is a blank focus of the ellipse described by the moon's orbit (the other focus occupied by the Earth). Dark Moon Lilith is often employed in astrological chart readings. "The Dark Moon describes our relationship to the absolute, to sacrifice as such, and shows how we let go." (Joëlle de Gravelaine in "Lilith und das Loslassen", Astrologie Heute Nr. 23)

The third astrological Lilith is the moon's apogee point (the point at which it is furthest in its orbit from the Earth), or "Black Moon" Lilith. It is said to signify instinctive and emotional intelligence in astrological charts.[citation needed]

Lilith in popular culture

See also

References

- Talmudic References: b. Erubin 18b; b. Erubin 100b; b. Nidda 24b; b. Shab. 151b; b. Baba Bathra 73a-b

- Kabbalist References: Zohar 3:76b-77a; Zohar Sitrei Torah 1:147b-148b; Zohar 2:267b; Bacharach,'Emeq haMelekh,19c; Zohar 3:19a; Bacharach,'Emeq haMelekh,102d-103a; Zohar 1:54b-55a

- Dead Sea Scroll References: 4QSongs of the Sage/4QShir; 4Q510 frag.11.4-6a//frag.10.1f; 11QPsAp

- An overview of the Lilith Mythos including analysis of the Burney Relief

- Kramer's Translation of the Gilgamesh Prologue. Kramer, Samuel Noah. "Gilgamesh and the Huluppu-Tree: A reconstructed Sumerian Text." Assyriological Studies of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 10. Chicago: 1938.

Notes

- ^ http://www.paganwiki.org/index.php?title=Lilith

- ^ http://www.lilitu.com/lilith/khephrel.html

- ^ http://www.circleamaurot.com/Deities-html/lilithleg.html

- ^ http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~humm/Topics/Lilith/relief_question.html#KRAEMERCRIT

- ^ a b http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~humm/Topics/Lilith/gilgamesh.html

- ^ http://www.deliriumsrealm.com/delirium/articleview.asp?Post=384

- ^ See also Lamia (mythology).

- ^ http://gnosis.org/lilith.htm

- ^ http://www.deliriumsrealm.com/delirium/articleview.asp?Post=333

- ^ http://www.deliriumsrealm.com/delirium/articleview.asp?Post=179#sammael

- ^ http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~humm/Topics/Lilith/jacob_ha_kohen.html

- ^ http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~humm/Topics/Lilith/aNePics.html

- ^ http://www.ritmanlibrary.nl/c/p/exh/kabb/kab_pheb_25.html

- ^ http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~humm/Topics/Lilith/origin.html

- ^ http://www.acs.ucalgary.ca/~elsegal/Shokel/950206_Lilith.html

- ^ a b c http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith/intro.html

- ^ http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith/ch2outln.html

- ^ a b http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith/faust.html

- ^ a b c d http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith/lamia.html

- ^ http://www.ancientlibrary.com/smith-bio/1953.html

- ^ http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith/labelle.html

- ^ a b c http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith/ch3outln.html

- ^ http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith/prb.html

- ^ a b c http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith/ladylil.html

- ^ http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith/bodybeau.html

- ^ http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith/edenb.html

- ^ http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith/ch2outln.html

- ^ http://weberstudies.weber.edu/archive/archive%20A%20%20Vol.%201-10.3/vol.%2010.2/10.2Seidel.htm

- ^ See also Neopaganism.

- ^ http://feminism.eserver.org/theory/papers/lilith

- ^ http://home.comcast.net/~max555/rites/lilith-ritus.html

- ^ http://home.comcast.net/~max555/rites/lilith_1.htm

- ^ http://www.barbelith.com/topic/26134

- ^ http://www.geocities.com/digital3v14/texts/modluc.html

- ^ http://www.luciferian.org/index.php?col=modluc

- ^ http://www.chaostatic.com/paradigm/writings/black-witchcraft.php

- ^ http://www.stregheria.com/Marguerite.htm

- ^ See also Aradia (goddess).

- ^ http://www.whitedragon.org.uk/articles/lillith.htm

- ^ http://www.lilithinstitute.com/history.htm

- ^ http://groups.msn.com/HOROSCOPESCHAT/lilithchiron.msnw

External links

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Lilith

- Collection of Lilith information and links by Alan Humm

- International standard Bible Encyclopedia: Night-Monster

- Lilith InstituteA Center for the Study of Sacred Text, Myth and Ritual

- Chapter on 'Lilith' from The Hebrew Goddess by Robert Graves and Raphael Patai