1955 Indonesian legislative election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

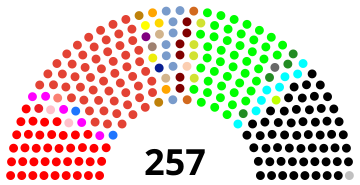

All 257 seats of the DPR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered | 43,104,464[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 91.54%[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results by electoral district | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results by regency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of Indonesia |

|---|

|

Legislative elections were held in Indonesia on 29 September 1955, to elect the 257 members of the People's Representative Council, the country's national legislature. The elections were the first national election held since the end of the Indonesian National Revolution, and saw over 37 million valid votes cast in over 93 thousand polling locations. The result of the election was inconclusive, as no party was given a clear mandate. The legislature which was elected through the election would eventually be dissolved by President Sukarno in 1959, through Presidential Decree number 150.

Background

The first elections were originally planned for January 1946, but because the Indonesian National Revolution was still underway, this was not possible. After the war, every cabinet had elections in its program. In February 1951 the Natsir cabinet introduced an election bill, but the cabinet fell before it could be debated. The next cabinet, led by Sukiman did hold some regional elections.[4] Finally, in February 1952, the Wilopo cabinet introduced a bill for voter registration. Discussions in the People's Representative Council did not start until September because of various objections from the political parties. According to Feith, there were three factors. Firstly, legislators were worried about losing their seats; secondly they were worried about a possible swing to Islamic parties and thirdly an electoral system in accordance with the Provisional Constitution of 1950 would mean less representation for regions outside Java.[5]

Given the fact that cabinets had fallen after introducing controversial measures, there was reluctance to introduce an election bill and there were concerns about possible political conflicts caused by electioneering.[6] However, many political leaders wanted elections as the existing legislature was based on a compromise with the Netherlands (the erstwhile colonial power) and as such had little popular authority. They also believed elections would bring about greater political stability.[7] The "17 October 1952 affair", when armed soldiers in front of the palace demanded dissolution of the legislature, led to greater demands from all parties for early elections. By 25 November, an elections bill had been submitted to the People's Representative Council. After 18 weeks of debate and 200 proposed amendments, the bill passed on 1 April 1953 and became law on 4 April. It stipulated one member of the legislature for 150,000 residents and gave the right to vote to everybody over the age of 18, or who was or had been married.[8] Once the bill had passed the cabinet began appointing members of the Central Electoral Committee. This was to have one member from each government party and an independent chairman. However, the Indonesian National Party (PNI) protested that they had no members on the committee, and this dispute was still unresolved when the cabinet fell on 2 June.[9]

On 25 August 1953, the new prime minister, Ali Sastroamidjojo, announced a 16-month schedule for elections starting from January 1954. On 4 November the government announced a new Central Electoral Committee chaired by PNI member S. Hadikusomo and including all the parties represented in the government, namely Nahdatul Ulama (NU), the Indonesian Islamic Union Party (PSII) the Indonesian People's Party (PRI), the National People's Party (PRN), the Labor Party and the Peasants Front of Indonesia (BTI), as well as the government-supporting Islamic Education Movement (Perti) and the Indonesian Christian Party (Parkindo).[10]

Campaign

According to Feith, the first phase of the election campaign began on 4 April 1953 when the election bill passed into law, and the second phase when the Central Electoral Committee approved the party symbols on 31 May 1954.[11]

At the time the bill passed into law, the cabinet was a coalition of the Islamic-based Masjumi and the nationalistic PNI. The next two successive cabinets were coalitions led by one of the two aforementioned parties with the other in opposition. Therefore, the main issue of the campaign was the debate between these two parties over the role of Islam in the state. Masjumi denied aiming for an Islamic state while the PNI emphasized that their pro-Pancasila stance was not anti-Islam as Masjumi sought to portray. The other two main and major Islamic parties, the NU and the PSII, supported Masjumi in this debate. A third factor was the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI), which campaigned on such significant issues like poverty due to the continued imperialist-leaning/-influenced nature of the government's cabinet policy. Masjumi tried to draw a clear line between the PKI and other political parties, accusing it of being a puppet element and a tool of Moscow in the country, as well as of seeking to influence and then spread communist ideology across Indonesia.[12]

Party programs were rarely widely discussed during the campaign. Party symbols with or without campaign slogans were displayed on most streets and thoroughfares in cities, towns and villages all across the country, as well as on private homes, public buildings, buses and trains, trees and even calendars. The PKI made extraordinary efforts to promote its symbol, as seen in their displaying it everywhere, from political posters to simple graffiti to newspapers, to make sure people everywhere saw and noticed it. The PKI's election campaign was based around social activities such as organizing tool-sharing programs for farmers and leading and directing the building of irrigation canals and channels for agriculture and the peasantry. As mentioned earlier, the party was looking beyond the election to build a permanent basis of widespread and large-scale support throughout Indonesia.[13]

In the last few months of the election campaign, the major parties focused on educating and mass-informing voters in areas where they had managed to establish village-level influence, organization and control. This phase included persuasion as well as threats.[14]

All through September, party leaders constantly traveled around the country to promote their parties, themselves and their political ideologies. Daily party-newspapers and magazines were printed in constantly-increasing numbers and given away for free. The articles in such political-dailies and media like these attacked rival parties and extolled their own. In the villages across Indonesia, the emphasis shifted from large-scale mass rallies to small-scale meetings and gatherings and house-to-house canvassing of political support.[15]

According to former agent Joseph Smith, the CIA covertly gave a million dollars to the centrist Masyumi Party to reduce support for Sukarno and the Communist Party of Indonesia during the election.[16]

Preparations and polling day

Although in April 1954 the Central Electoral Committee had announced that the election would be held on 29 September the following year, by July and early August, preparations had fallen behind schedule The appointment of members of polling station committees planned to start on 1 August did not begin in many regions until 15 September. In his independence day address on 17 August, President Sukarno said that anybody putting obstacles in way of elections was a "traitor to the revolution". On 8 September, the information minister said that elections would be held on September 29 except in a few areas where preparations were not complete. Eventually, as a result of "feverish activity", polling station committees were ready on election day.[17]

In the run up to polling day, rumors spread, including a widespread poisoning scare in Java. There was also hoarding of goods. In many parts of country there was a spontaneous and unannounced curfew for several nights before polling day.

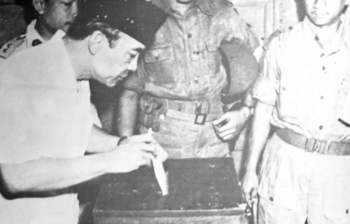

On polling day itself, many voters were waiting to cast their ballots by 7am. The day was peaceful as people realized nothing bad was going to happen. A total of 87.65% of voters cast a valid vote and 91.54% voted. Allowing for deaths between registration and polling, only about 6% did not vote.[18]

Electoral system

The 257 seats of the People's Representative Council were elected in 16 multi-member constituencies by proportional representation.

Results

The election was a major success for the NU, which saw its number of seats in the People's Representative Council increase from 8 to 45. A surprise was the poor showing of Masyumi, the Socialist Party and Murba. There was a large gap between the "big 4" (PNI, Masjumi, NU and PKI, with more than three-quarters of the vote shared among them) and the rest of the parties, but contrary to expectations, the number of parties actually increased - there were now 28 with seats in the legislature as opposed to 20 before the election, with the largest party holding only 22% of seats.

The distribution of votes was uneven across the country. The PNI won 85.97% of its vote in Java, the NU 85.6% and the PKI 88.6%, despite the fact that only 66.2% of the population lived on Java. Conversely only 51.3% of Masjumi's vote came from Java, and it established itself as the leading party for the one-third of people living outside Java.[19][20]

Aftermath

The poor showing of the parties in the cabinet of Prime Minister Burhanuddin Harahap was a major blow. The parties who did better, such as the NU and the PSII were "reluctant" cabinet members with a weak standing. This left the government with the choice of making major concessions to the NU and PSII or seeing them leave the cabinet. With no clear electoral verdict, it was back to inter-party politicking and bargaining. The lack of a clear outcome discredited the existing political system.

The new People's Representative Council convened on 4 March 1956. It was to last four years. In his opening speech, President Sukarno called for an Indonesian form of democracy, and over the next few years, he would speak more about his concept (konsepsi) of a new system of government. In 1957, the era of Liberal Democracy came to an end with the establishment of Guided Democracy. Indonesia would have to wait until 1999 for its next free national elections.[20][21][22]

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ Feith 1999, p. 5.

- ^ Feith 2007, p. 429.

- ^ Feith 2007, p. 579.

- ^ Feith (2007) p273

- ^ Feith (2007) p274-275

- ^ Feith (2007) p276

- ^ Feith (2007) p277

- ^ Feith (2007) p278-280

- ^ Feith (2007) p281

- ^ Feith (2007) p348

- ^ Feith (1999) p10

- ^ Feith (1999) p15-19

- ^ Feith (1999) p27-36

- ^ Feith (1999) p37

- ^ Feith (2007) p427

- ^ Smith (1976) pp110-111

- ^ Feith (2007) p424-426

- ^ Feith (2007) p429

- ^ Feith (2007) p436-437

- ^ a b Ricklefs (1991) p238

- ^ Feith (2007) p437

- ^ Friend(2003) p406

Sources

- Feith, Herbert (2007) [1962]. The Decline of Constitutional Democracy in Indonesia. Singapore: Equininox Publishing (Asia) Pte Ltd. ISBN 978-979-3780-45-0.

- Feith, Herbert (1999). Pemilihan Umum 1955 di Indonesia [The Indonesian Elections of 1955] (in Indonesian). Kepustakaan Popular Gramedia. ISBN 979-9023-26-2.

- Friend, Theodore (2003). Indonesian Destinies. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01834-6.

- Ricklefs, M.C. (1991) A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1200. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4480-7

- Sekretariat Negara Republik Indonesia (1975) 30 Tahun Indonesia Merdeka: Jilid 2 (1950-1964) (30 Years of Indonesian Independence: Volume 2 (1950-1964)) No ISBN

- Smith, Joseph Burkholder (1976). Portrait of a Cold Warrior. New York: Putnam. ISBN 9780399117886.