Lollardy

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe,[1] a Catholic theologian who was dismissed from the University of Oxford in 1381 for criticism of the Roman Catholic Church. The Lollards' demands were primarily for reform of Western Christianity. They formulated their beliefs in the Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards.

Etymology

Lollard, Lollardi, or Loller was the popular derogatory nickname given to those without an academic background, educated (if at all) only in English, who were reputed to follow the teachings of John Wycliffe in particular, and were certainly considerably energized by the translation of the Bible into the English language. By the mid-15th century, "lollard" had come to mean a heretic in general. The alternative, "Wycliffite", is generally accepted to be a more neutral term covering those of similar opinions, but having an academic background.

The term is said to have been coined by the Anglo-Irish cleric Henry Crumpe, but its origin is uncertain. The earliest official use of the name in England occurs in 1387 in a mandate of the Bishop of Worcester against five "poor preachers", nomine seu ritu Lollardorum confoederatos.[2] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, it most likely derives from Middle Dutch lollaerd ("mumbler, mutterer"), from a verb lollen ("to mutter, mumble"). The word is much older than its English use; there were Lollards in the Netherlands at the beginning of the 14th century who were akin to the Fraticelli, Beghards, and other sectaries similar to the recusant Franciscans.[2]

Originally the Dutch word was a colloquial name for a group of the harmless buriers of the dead during the Black Death, in the 14th century, known as Alexians, Alexian Brothers or Cellites. These were known colloquially as lollebroeders (Middle Dutch for "mumbling brothers"), or Lollhorden, from Old High German: lollon ("to sing softly"), from their chants for the dead.[3] Middle English loller (akin to the verb loll, lull, the English cognate of Dutch lollen "to mutter, mumble") is recorded as an alternative spelling of Lollard, while its generic meaning "a lazy vagabond, an idler, a fraudulent beggar" is not recorded before 1582.[citation needed]

Two other possibilities for the derivation of Lollard are mentioned by the Oxford English Dictionary:[4]

- Latin lolium, a weedy vetch (tares), supposedly a reference to the biblical Parable of the Tares (Matthew 13:24–30);

- the surname “Lolhard” of an eminent Franciscan preacher in Guyenne, who converted to the Waldensian way. The region of Guyenne was at that time under English dominion, and his preaching influenced pious lay English. He was burned at Cologne in the 1370s. Earlier, another Waldensian teacher, also named “Lolhard”, was tried for heresy in Austria in 1315.[5]

Beliefs

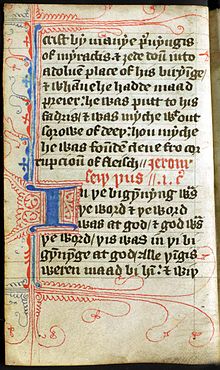

Lollardy was a religion of vernacular scripture.[6] Lollards opposed many practices of the Catholic church. Anne Hudson has written that a form of sola scriptura underpinned Wycliffe's beliefs, but distinguished it from the more radical ideology that anything not permitted by scripture is forbidden. Instead, Hudson notes that Wycliffe's sola scriptura held the Bible to be "the only valid source of doctrine and the only pertinent measure of legitimacy."[7]

With regard to the Eucharist, Lollards such as John Wycliffe, William Thorpe, and John Oldcastle, taught a view of the real presence of Christ in Holy Communion known as "consubstantiation" and did not accept the doctrine of transubstantiation, as taught by the Roman Catholic Church.[8][9] The Plowman's Tale, a 16th-century Lollard poem, argues that theological debate about orthodox doctrine is less important than the Real Presence:[10]

I say sothe thorowe trewe rede

His flesh and blode, through his mastry

Is there/ in the forme of brede

Howe it is there/ it nedeth not stryve

Whether it be subgette or accydent

But as Christ was/ when he was on-lyve

So is he there verament.[11]

[In modern English:]

I say the truth through true understanding:

His flesh and blood, through his subtle works,

Is there in the form of bread.

In what manner it is present need not be debated,

Whether as subject or accident,

But as Christ was when he was alive,

So He is truly there.[12]

Wycliffite teachings on the Eucharist were declared heresy at the Blackfriars Council of 1382. William Sawtry, a priest, was reportedly burned in 1401 for his belief that "bread remains in the same nature as before" after consecration by a priest. In the early 15th century a priest named Richard Wyche was accused of false doctrine. When asked about consecration during his questioning, he repeated only his belief in the Real Presence. When asked if the host was still bread even after consecration, he answered only: "I believe that the host is the real body of Christ in the form of bread". Throughout his questioning he insisted that he was "not bound to believe otherwise than Holy Scripture says". Following the questioning, Wyche eventually recanted, after he was excommunicated and imprisoned.[13][14] A suspect in 1517 summed up the Lollards' position: "Summe folys cummyn to churche thynckyng to see the good Lorde – what shulde they see there but bredde and wyne?"[15][16]

Lollard teachings on the Eucharist are attested to in numerous primary source documents; it is the fourth of the Twelve Conclusions and the first of the Sixteen Points on which the Bishops accuse Lollards. It is discussed in The Testimony of William Thorpe, the Apology for Lollard Doctrines,[17] Jack Upland, and Opus Arduum.[18]

Simon Fish was condemned for several of the teachings in his pamphlet Supplication for the Beggars including his denial of purgatory and teachings that priestly celibacy was an invention of the Antichrist. He argued that earthly rulers have the right to strip Church properties, and that tithing was against the Gospel.[19][20]

The Lollards did not believe that the church practices of baptism and confession were necessary for salvation. They considered praying to saints and honouring of their images to be a form of idolatry. Oaths, fasting and prayers for the dead were thought to have no scriptural basis. They had a poor opinion of the trappings of the Catholic Church, including holy bread, holy water, bells, organs, and church buildings. They rejected the value of papal pardons.[6] Special vows were considered to be in conflict with the divine order established by Christ and were regarded as anathema.[21] Sixteenth-century martyrologist John Foxe described four main beliefs of Lollardy: opposition to pilgrimages and saint worship, denial of the doctrine of transubstantiation, and a demand for English translation of the Scriptures.[22]

One group of Lollards petitioned Parliament with The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards by posting them on the doors of Westminster Hall in February 1395. While by no means a central statement of belief of the Lollards, the Twelve Conclusions reveal certain basic Lollard ideas. The first Conclusion rejects the acquisition of temporal wealth by Church leaders, as accumulating wealth leads them away from religious concerns and towards greed. The fourth Conclusion deals with the Lollard view that the Sacrament of the Eucharist is a debatable doctrine that is not clearly defined in the Bible. Whether the bread remains bread or becomes the literal body of Christ is not specified uniformly in the gospels. The sixth Conclusion states that officials of the Church should not concern themselves with secular matters when they hold a position of power within the Church, since this constitutes a conflict of interest between matters of the spirit and matters of the State. The eighth Conclusion points out the ludicrousness, in the minds of Lollards, of the reverence that is directed toward images of Christ's suffering. "If the cross of Christ, the nails, spear, and crown of thorns are to be honoured, then why not honour Judas's lips, if only they could be found?"[23]

The Lollards stated that the Catholic Church had been corrupted by temporal matters and that its claim to be the true Church was not justified by its heredity. Part of this corruption involved prayers for the dead and chantries. These were seen as corrupt since they distracted priests from other work; instead, all should be prayed for equally. Lollards also had a tendency toward iconoclasm. Expensive church artwork was seen as an excess; they believed effort should be placed on helping the needy and preaching rather than working on expensive decorations. Icons were also seen as dangerous since many seemed to be worshipping the icons more fervently than they worshipped God.

Believing in a universal priesthood, the Lollards challenged the Church's authority to invest or to deny the divine authority to make a man a priest. Denying any special status to the priesthood, Lollards thought confession to a priest was unnecessary since according to them priests did not have the ability to forgive sins. Lollards challenged the practice of clerical celibacy and believed priests should not hold government positions as such temporal matters would likely interfere with their spiritual mission. Lollards also believed that people deserved access to a copy of their own bible. Many attempted to distribute translated copies however due to the lack of a printing press and low literacy levels it was difficult to accomplish this goal.[24]

Lollards did not follow restrictions for fasting and abstinence in the Catholic Church. In heresy proceedings against Margery Baxter it was presented as evidence that a servant girl found bacon in a pot of oatmeal during the first Saturday of Lent. Non-observance of dietary restrictions was used as evidence of heresy in another Norfolk case against Thomas Mone where it was alleged that a piglet was eaten for Easter dinner when eating meat was forbidden.[25]

History

Although Lollardy was denounced as a heresy by the Catholic Church, initially Wycliffe and the Lollards were sheltered by John of Gaunt and other anti-clerical nobility, who may have wanted to use Lollard-advocated clerical reform to acquire new sources of revenue from England's monasteries. The University of Oxford also protected Wycliffe and similar academics on the grounds of academic freedom and, initially, allowed such persons to retain their positions despite their controversial views. Lollards first faced serious persecution after the Peasants' Revolt in 1381. While Wycliffe and other Lollards opposed the revolt, one of the peasants’ leaders, John Ball, preached Lollardy. Prior to 1382, Lollard beliefs were tolerated in government as they believed in royal superiority. However, the government and royals were hesitant, as they did not want to encourage subjects to criticize religious powers.[26] The royalty and nobility then found Lollardy to be a threat not only to the Church, but to English society in general. The Lollards' small measure of protection evaporated. This change in status was also affected by the 1386 departure of John of Gaunt who left England to pursue the Crown of Castile.

A group of gentry active during the reign of Richard II (1377–99) were known as "Lollard Knights" either during or after their lives due to their acceptance of Wycliffe's claims. Henry Knighton, in his Chronicle, identifies the principal Lollard Knights as Thomas Latimer, John Trussell, Lewis Clifford, Sir John Peche (son of John Peche of Wormleighton), Richard Storey, and Reginald Hilton. Thomas Walsingham's Chronicle adds William Nevil and John Clanvowe to the list, and other potential members of this circle have been identified by their wills, which contain Lollard-inspired language about how their bodies are to be plainly buried and permitted to return to the soil whence they came. There is little indication that the Lollard Knights were specifically known as such during their lifetimes; they were men of discretion, and unlike Sir John Oldcastle years later, rarely gave any hint of open rebellion. However, they displayed a remarkable ability to retain important positions without falling victim to the various prosecutions of Wycliffe's followers occurring during their lifetimes.

Religious and secular authorities strongly opposed Lollardy. A primary opponent was Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, assisted by bishops like Henry le Despenser of Norwich, whom the chronicler Thomas Walsingham praised for his zeal.[27] Paul Strohm has asked: "was the Lollard a genuine threat or a political pawn, agent of destabilising challenge, or a hapless threat of self-legitimizing Lancastrian discourse?"[28]

As a prelude to the 16th-century Acts of Supremacy that mark the beginning of the English Reformation, De heretico comburendo was enacted in 1401 during the reign of Henry IV; traditionally heresy had been defined as an error in theological belief, but this statute equated theological heresy with sedition against political rulers.[28]

Oldcastle Revolt and persecution

By the early 15th century, stern measures were undertaken by Church and state which drove Lollardy underground. One such measure was the 1410 burning at the stake of John Badby, a layman and craftsman who refused to renounce his Lollardy. He was the first layman to suffer capital punishment in England for the crime of heresy.

John Oldcastle, a close friend of Henry V of England and the basis for Falstaff in the Shakespearean history Henry IV, Part 1, was brought to trial in 1413 after evidence of his Lollard beliefs was uncovered. Oldcastle escaped from the Tower of London and organized an insurrection, which included an attempted kidnapping of the king. The rebellion failed, and Oldcastle was executed. Oldcastle's revolt made Lollardy seem even more threatening to the state, and persecution of Lollards became more severe.

A variety of other martyrs for the Lollard cause were executed during the next century, including the Amersham Martyrs in the early 1500s and Thomas Harding in 1532, one of the last Lollards to be made victim. A gruesome reminder of this persecution is the 'Lollards Pit' in Thorpe Wood, now Thorpe Hamlet, Norwich, Norfolk, "where men are customablie burnt",[29] including Thomas Bilney.

Subsequent events and influence

Lollards were effectively absorbed into Protestantism during the English Reformation, in which Lollardy played a role. Since Lollards had been underground for more than a hundred years, the extent of Lollardy and its ideas at the time of the Reformation is uncertain and a point of debate.[30][31][32] Ancestors of Blanche Parry (the closest person to Elizabeth I for 56 years) and of Blanche Milborne (who raised Edward VI and Elizabeth I) had Lollard associations. However, many critics of the Reformation, including Thomas More, equated Protestants with Lollards. Leaders of the English Reformation, including Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, referred to Lollardy as well, and Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall of London called Lutheranism the "foster-child" of the Wycliffite heresy.[33] Scholars debate whether Protestants actually drew influence from Lollardy or whether they referred to it to create a sense of tradition.

Despite the debate about the extent of Lollard influence there are ample records of the persecution of Lollards from this period. In the Diocese of London, there are records of about 310 Lollards being prosecuted or forced to abjure from 1510 to 1532. In Lincoln diocese, 45 cases against Lollardy were heard in 1506–1507 and in 1521 there were 50 abjurations and 5 burnings of Lollards. In 1511, Archbishop Warham presided over the abjuration of 41 Lollards from Kent and the burning of 5.[34]

The extent of Lollardy in the general populace at this time is unknown, but the prevalence of Protestant iconoclasm in England suggests Lollard ideas may still have had some popular influence if Huldrych Zwingli was not the source, as Lutheranism did not advocate iconoclasm. Lollards were persecuted again between 1554 and 1559 during the Revival of the Heresy Acts under the Catholic Mary I, which specifically suppressed heresy and Lollardy.

The similarity between Lollards and later English Protestant groups such as the Baptists, Puritans, and Quakers also suggests some continuation of Lollard ideas through the Reformation.[35]

Representations in art and literature

The Roman Catholic Church used art as an anti-Lollard weapon. Lollards were represented as foxes dressed as monks or priests preaching to a flock of geese on misericords.[36] These representations alluded to the story of the preaching fox found in popular medieval literature such as The History of Reynard the Fox and The Shifts of Raynardine. The fox lured the geese closer and closer with its eloquent words until it was able to snatch a victim to devour. The moral of the story being that foolish people are seduced by false teachers.

See also

- Margery Baxter

- Ecclesiae Regimen

- Euchites

- General Prologue of the Wycliffe Bible

- Hussites

- William Langland

- Nicholas Love

- Thomas Netter

- Piers Plowman

- Piers Plowman tradition

- Waldensians

Citations

- ^ Roberts, Chris (2006), Heavy Words Lightly Thrown: The Reason Behind Rhyme, Thorndike Press, ISBN 0-7862-8517-6.

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lollards". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ cf. English lullaby, and the modern Dutch and German lallen "to babble, to talk drunkenly": "lallen". Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache.

- ^ "Lollard". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- ^ van Bright, T.J. (1886) [1660]. The Bloody Theater or Martyrs Mirror of the Defenseless Christians. Translated by Joseph F. Sohm (Third English ed.). Scottsdale, Pennsylvania: Herald Press.

- ^ a b Aston, Margaret (1996). "Lollardy". Lollardy - Oxford Reference. Encyclopedia of the Reformation. ISBN 978-0-19-506493-3. Retrieved 31 May 2017. – via OUP (subscription required)

- ^ Hudson 1988, p. 280.

- ^ Walker, Greg (6 February 2013). Reading Literature Historically: Drama and Poetry from Chaucer to the Reformation. Edinburgh University Press. p. 152. ISBN 9780748681037.

- ^ Hornbeck, J. Patrick (10 September 2010). What is a lollard?: dissent and belief in late medieval England. Oxford University Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780199589043.

- ^ Barr, Helen (1994). Signes and Sothe: Language in the Piers Plowman Tradition. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-419-2.

- ^ McCarl, Mary Rhinelander, ed. (1997). The Plowman's Tale: The c. 1532 and 1606 Editions of a Spurious Canterbury Tale. New York: Garland. pp. 21–40.

On the dating of "The Plowman's Tale", see Andrew N. Warn, "The Genesis of The Plowman's Tale, Yearbook of English Studies 2" 1972

- ^ Hardwick, Paul (2011). English Medieval Misericords: The Margins of Meaning. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. p. 60. ISBN 9781843836599.

- ^ Hudson 1988, p. 284.

- ^ Stone, Darwell (1 October 2007). A History of the Doctrine of the Holy Eucharist. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59752-973-0.

- ^ Hudson 1988, p. 285.

- ^ Crossley-Holland, Nicole (1 January 1991). Eternal Values in Mediaeval Life. Saint David's Univ. College. ISBN 978-0-905285-31-3.

- ^ Wycliffe, John; Camden Society (Great Britain); Todd, James Henthorn (1842). An apology for Lollard doctrines. London : Printed for the Camden Society, by J.B. Nichols. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ^ Hudson 1988, pp. 285–286.

- ^ Marc’hadour, Germain (1 June 1984). "Margaret Aston, "William White's Lollard Followers"". Moreana. 21 (Number 82) (2): 18. doi:10.3366/more.1984.21.2.4. ISSN 0047-8105.

- ^ Rollison, David (11 August 2005). The Local Origins of Modern Society: Gloucestershire 1500-1800. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-91333-6.

- ^ Gasse, Roseanne (1 January 1996). "Margery Kempe and Lollardy". Magistra. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2017. – via HighBeam (subscription required)

- ^ Walker, Greg (1 May 1993). "Heretical Sects in Pre-Reformation England". History Today. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2017. – via HighBeam (subscription required)

- ^ Hudson 1988, p. 306.

- ^ Bucholz, R. (2013). Early modern england 1485-1714 : A narrative history. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.|url=https://books.google.com/books/about/Early_Modern_England_1485_1714.html?id=fvm4DwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Woolgar, C. M. (2016). The Culture of Food in England, 1200–1500. Yale University Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780300181913.

- ^ Bucholz, R. (2013). Early modern england 1485-1714 : A narrative history. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. |url=https://books.google.com/books/about/Early_Modern_England_1485_1714.html?id=fvm4DwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Walsingham. Historia Anglicana. Vol. 2. p. 189..

- ^ a b Kelly, Stephen (29 June 2017). Hiscock, Andrew; Wilcox, Helen (eds.). "The Pre-Reformation Landscape". The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern English Literature and Religion. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199672806.013.2. ISBN 978-0-19-967280-6. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ Rackham, Oliver (1976). Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. JM Dent & Sons. pp. 137–38. ISBN 0-460-04183-5..

- ^ Aston, Margaret E. (1964). "Lollardy and the Reformation: Survival or Revival?". History. 49 (166): 149–170. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1964.tb01098.x. ISSN 0018-2648.

- ^ Dickens, A. G. (1989). The English Reformation (2nd ed.). Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 46–60. ISBN 978-0271028682.

- ^ Stansfield-Cudworth, R. E. (2021). "From Minority to Maturity: The Evolution of Later Lollardy". Socio-Historical Examination of Religion and Ministry. 3 (2): 325–352. doi:10.33929/sherm.2021.vol3.no2.07. ISSN 2637-7500. S2CID 248602354.

- ^ Potter, R. "Documents on the changing status of the English Vernacular, 1500–1540". RIC. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- ^ Dickens, A.G. (1959). Lollards & Protestants in the Diocese of York, 1509–58. A&C Black. ISBN 9780907628057.

- ^ Spufford, Margaret, ed. (1995). The World of Rural Dissenters, 1520–1725. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521410618.

- ^ Benton, Janetta (January 1997). Holy Terrors: Gargoyles on Medieval Buildings. Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-0-7892-0182-9., p. 83

General references

- Arnold, John H. (2019). "Voicing Dissent: Heresy Trials in Later Medieval England". Past and Present. 245 (1): 3–37. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtz025.

- Aston, Margaret E. (1984). Lollards and Reformers: Images and Literacy in Late Medieval Religion. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-0907628187.

- Aston, Margaret E.; Richmond, Colin F., eds. (1997). Lollardy and the Gentry in the Late Middle Ages. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 978-0312173883.

- Dickens, A. G. (1989). The English Reformation (2nd ed.). Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0271028682.

- Duffy, Eamon (1992). The Stripping of the Altars. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300108286.

- Forrest, Ian (2005). The Detection of Heresy in Late Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199286928.

- Hudson, Anne M. (1988). "The Ideology of Reformation". The Premature Reformation: Wycliffite Texts and Lollard History. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198227625.

- Lowe, Ben (2004). "Teaching in the 'Schole of Christ': Law, Learning, and Love in Early Lollard Pacifism". Catholic Historical Review. 90 (3): 405–38. doi:10.1353/cat.2004.0142. S2CID 153795536..

- Lutton, Robert (2006). Lollardy and Orthodox Religion in Pre-Reformation England. Woodbridge and Suffolk, UK: Boydell and Brewer. ISBN 978-1843836490.

- McFarlane, K. B. (1952). John Wycliffe and the Beginnings of English Nonconformity. London: English Universities Press. ISBN 978-0340166482.

- McSheffrey, Shannon; Tanner, Norman P., eds. (2003). Lollards of Coventry, 1486–1522. Royal Historical Society, Camden, Fifth Series, 23. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521830836. OCLC 799426323.

- McSheffrey, Shannon (2005). "Heresy, Orthodoxy and English Vernacular Religion 1480–1525". Past and Present. 186 (1): 47–80. doi:10.1093/pastj/gti001. JSTOR 3600851.

- Rex, Richard (2002). The Lollards: Social History in Perspective. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0333597521.

- Robson, John Adam (1961). Wyclif and the Oxford Schools: The Relation of the "Summa de Ente" to Scholastic Debates at Oxford in the Later Fourteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521089326.

- Spufford, Margaret, ed. (1995). The World of Rural Dissenters, 1520–1725. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521410618.

- Thomson, John A. F. (1965). The Later Lollards, 1414–1520. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198213765.

External links

- The Lollard Society—society dedicated to providing a forum for the study of the Lollards

- "John Wyclif and the Lollards" (45 mins.; discussion); episode of In Our Time, BBC Radio 4