Clifton Hill, Victoria

| Clifton Hill Melbourne, Victoria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Aerial view of Clifton Hill looking north to Queens Parade and Merri Creek. Hoddle Highway is the main road on the left and Darling Gardens is far left. | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°47′20″S 144°59′56″E / 37.789°S 144.999°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 6,606 (SAL 2021)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 3068 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 38 m (125 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 1.57 km2 (0.6 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 4 km (2 mi) from Melbourne | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Yarra | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Richmond | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

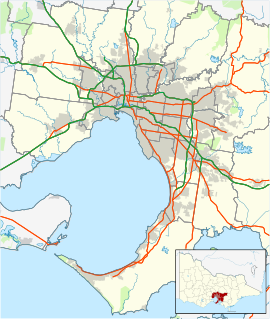

Clifton Hill is an inner-city suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 4 km (2.5 mi) north-east of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the City of Yarra local government area. Clifton Hill recorded a population of 6,606 at the 2021 census.[2]

Described in the 1880s as the "Toorak of Collingwood",[3] Clifton Hill fell out of favour, along with much of inner Melbourne, by the mid 20th century. Later becoming a centre of Melbourne's bohemianism, the suburb has undergone rapid gentrification in recent years, with renewed interest in its inner city location and well preserved Victorian and Edwardian housing stock. Clifton Hill is now considered one of Melbourne's most liveable suburbs,[4] and is consequently becoming increasingly less affordable, with the median property price increasing from 112% to 160% of the Melbourne metropolitan median in the decade to 1996, and 180% (AUD1.48 million) by 2017.[5]

Clifton Hill is located immediately adjacent to Fitzroy North, with which it shares the same postcode. Along with Carlton North and Fitzroy North, Clifton Hill has unusually spacious and picturesque streets, being part of a well preserved government subdivision laid out by Clement Hodgkinson in the 1860s, and most unlike the smaller crowded streets of the majority of inner Melbourne. The border between Clifton Hill and Fitzroy North is Queens Parade and Smith Street while Clifton Hill's border with Collingwood is Alexandra Parade. Merri Creek defines the eastern and northern borders of Clifton Hill with Northcote and Fairfield.

History

Foundation of East Collingwood

In the mid-1850s, East Collingwood was known as an unsanitary flood-prone polluted flat. It was 'Melbourne's multi-problem suburb', described as "An ideal case study in the origins of pollution. The residents were soon wading in (their) own muck ... Collingwood became a cesspool for refuse." The area was "akin to a swamp and the few who ventured forth were looked upon after their return as people who had performed a somewhat perilous journey."[6]

The municipality of East Collingwood was proclaimed on 24 April 1855 by Collingwood's businessmen to improve the district, initially only including the areas which would later be known as Collingwood and Abbotsford. The municipality was known as East Collingwood, as, at the time, the term 'Collingwood' included what is now known as Fitzroy,[7] then a ward of the City of Melbourne and later becoming the City of Fitzroy.

Annexation

In the 1850s, the land that would become Clifton Hill was crown land, but unincorporated, serviced by unsurveyed tracks leading to Northcote and bounded by the surveyed roads of Heidelberg Road and Hoddle Street,[6] which provided access to private quarries in the area, which is between Ramsden and Roseneath Streets, Clifton Hill nowadays, as well as the City of Melbourne quarry, located between Yambla Street and the Merri Creek.

Within a few months,[7] the East Collingwood Local Committee sought permission for East Collingwood to annex what is now Clifton Hill. This annexation was controversial. Henry Groom, a City of Melbourne Councillor, declared, not surprisingly, "The freeholders of Clifton Hill have no desire to depreciate the value of their property by suffering it to be annexed to a swamp which to drain itself would drain our resources."[8]

East Collingwood was successful in its acquisition of Clifton Hill, and also unsuccessfully pursued the annexation of Studley Park.[6] This formed the City of Collingwood, which remained essentially intact until it was amalgamated, along with the City of Fitzroy and the City of Richmond, into the City of Yarra in 1994.

Early development

While much of Richmond, Fitzroy and Collingwood had been laid out by speculators anxious to increase profits, Clifton Hill was a professionally laid out suburb. Clement Hodgkinson, as Victorian Assistant-Commissioner of Crown Lands and Survey (1861–74), was responsible for the government subdivisions of Carlton (1860), North Carlton, North Fitzroy and Clifton Hill (1865–9), Hotham Hill (1866), South and North Parkville (1868–9). Under his supervision, suburban planning employed the grid system used by Robert Hoddle, Hodgkinson's predecessor.

Consequently, Smith, Wellington and Hoddle Streets were extended north to connect with Heidelberg Road (now Queens Parade), and planning of Clifton Hill proceeded on a more organised basis than that of the remainder of the municipality, including reservation of land for public recreation purposes.[9]

During the following years, disputes arose as competing interests proposed different locations and routes for infrastructure to be constructed through the municipality, such as major roads and bridges. The North, South, 'flat' and 'slope' of the municipality disputed issues that were all seen to benefit one faction to the detriment of another.[6]

A large drain, known as the Reilly Street drain (now located under Alexandra Parade), was constructed to drain the Crown land in Clifton Hill, in order to increase profits for the government when selling the land to private developers. However, this scheme failed when the drain overflowed onto the Collingwood Flat in the first winter after it was constructed. The Reilly Street drain became notorious and continued to be a hazard as occasionally someone fell in and was drowned.[8]

Despite continuing urbanisation and population growth, the municipality remained mostly of rural appearance, with butchers in the south of the municipality holding grazing leases on Crown land in Clifton Hill and on the paddocks on the Collingwood Flat.[8]

Residential development

As a sentiment of enduring settlement, neighbourhood and civic pride began to develop in the residents of Clifton Hill, demand for public open space such as sporting grounds and public parks and gardens increased.[6] In 1862, a petition from the 'Municipal District of East Collingwood' was presented to the Legislative Assembly citing the good work of the local Vigilance Committee towards improving Clifton Hill. Often, these reserves also served as common grazing areas when not used for recreational activities. It was at this time that the land that would become the Darling Gardens was reserved.

The land in Clifton Hill began to be sold in 1864 and the area boomed, along with the rest of Melbourne, in the 1880s. Between, it was reported, 'the progress ... was almost a backward one. It truly was "a howling wilderness".[3]

Clifton Hill received its current name, distinguishing it from the remainder of Collingwood, from Clifton Farm, one of the first properties in the area. The word "Hill" was added by land developer John Knipe to spruik his new estate, the first subdivision of which, being 64 freehold properties, was auctioned by Knipe, George and Co. on 18 September 1871.[10]

During the 1880s boom, the population of Collingwood increased by half, from 23,829 (1881) to 35,070 (1891), and the number of dwellings rose from nearly 5,000 to 7,000. As most of the remainder of the municipality had already been developed, this mainly represented the urbanisation of Clifton Hill.

By the end of the 1880s, the area was described as "a residential suburb.... which has of late years been extensively built on with a good class of houses and numerous handsome shops. It has an elevated position, and commands an excellent view of the metropolis."[11] The district was soon "covered with innumerable cottages of the comfortable working classes; street after street; row after row, of these neat brick buildings."[12]

The Melbourne Tramway & Omnibus Company's cable tramway reached Clifton Hill in 1887,[13] providing convenient transport to the commercial district of Smith Street, Collingwood, Bourke Street in the City Centre, as well as spurring development of the local Queens Parade commercial district around the tram terminus.

The elevated location, planned wide streets and calibre of housing resulted in Clifton Hill being described in the 1886 as "The Toorak of Collingwood".[3]

Later development

Clifton Hill's residential attraction lessened entering the 20th century as middle class housing grew and industry took up land for factories, mostly in the South of the suburb, adjacent to Alexandra Parade. By the 1960s, the number of intrusive blocks of flats were built, particularly on prominent streets such as South Terrace, overlooking the Darling Gardens.[6]

By the late 20th century, the amenity laid down during development in the 1880s was recognised once more, and Clifton Hill underwent rapid gentrification, with the median property price increasing from 112% to 160% of the Melbourne metropolitan median in the decade to 1996, and 180% by 2017. Furthermore, by this time, the majority of industry had closed or moved elsewhere, freeing industrial sites for residential redevelopment. The former City of Melbourne Quarry at the corner of Ramsden and Yambla Streets, which had become a tip by the 1960s, had been redeveloped into an attractive park, including an adventure playground and skate park, further adding to the amenity of the area.

Little Hollywood

The intersection between Queens Parade and Gold Street was referred to by locals as "Little Hollywood". However, because of development and badly leased commercial properties most of the film makers in recent years have moved to the neighbouring suburb of Fitzroy. Particularly, the "Hollywood End" of Gertrude Street.

Description

Accommodation in this leafy suburb consists largely of single and double storey Victorian and Edwardian era dwellings, comprising a mixture of free standing houses, and semi-attached rows of terraces. The suburb is a relatively intact example of late 19th century and early 20th century development, and is now almost completely protected by heritage planning controls.

Hoddle Street bisects the suburb, dividing it into western and eastern precincts. The suburb is well served by parks and gardens, including Darling Gardens and Mayor's Park (western precinct) and Quarries Park (eastern precinct).

An attractive local shopping strip is located along Queens Parade, on the border with Fitzroy North, consisting of mainly Victorian era shopfronts in a reasonable state of preservation. Dwelling density in Clifton Hill is significantly lower than the remainder of the former City of Collingwood, which also included the suburbs of Collingwood and Abbotsford.

Transport

Major road arteries passing through the suburb include Queens Parade, Heidelberg Road, Alexandra Parade and Hoddle Street. The Eastern Freeway terminates at Alexandra Parade, and provides access to the outer Eastern and Southeastern suburbs.

Clifton Hill railway station forms the junction between the Mernda and Hurstbridge lines, and is located at the corner of Hoddle and Ramsden Streets, opposite Mayors Park and the Darling Gardens. Express and stopping all stations services frequently operate from the station, taking between 9 and 12 minutes to Flinders Street in the city centre.

Tram route 86 runs along Queens Parade, and provides access to Smith Street and Bourke Street in the centre of the city and to Docklands and Bundoora.

Several bus routes run along Hoddle Street and interchange at the railway station.

Crime

Clifton Hill was the site of the 1987 Hoddle Street massacre, in which 19-year-old Julian Knight embarked on the 45-minute shooting spree killing seven people and injuring 19 before being arrested by police. Otherwise, Clifton Hill is seen as a relatively safe suburb and was ranked as the 11th most liveable suburb in Melbourne by Domain.com.au.[14]

Notable residents

- John Allan Aird (1892–1959) – Irrigation Commissioner[15]

- Wilfred Burchett (1911–1983) – journalist[16]

- Arnold Henry (1887–1979) – architect[17]

- George David Langridge (1829–1891) – carpenter, auctioneer, building society founder, councillor and acting premier[18]

See also

- City of Collingwood – Clifton Hill was previously within this former local government area.

- Hoddle Street massacre

References

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Clifton Hill (suburb and locality)". Australian Census 2021 QuickStats. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ a b Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Clifton Hill (Suburbs and Localities)". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Collingwood Mercury, 29 October 1886

- ^ [1]The Age 24 November 2011

- ^ [2] Archived 1 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine REIV, 1 October 2017

- ^ a b c d e f City of Yarra Heritage Review

- ^ a b "Collingwood Historical Society Inc". Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012. Collingwood Historical Society

- ^ a b c Barrett, The Inner Suburbs

- ^ Collingwood Conservation Study, p.164

- ^ The Argus 14 September 1871, page 8

- ^ A Sutherland, Victoria and its Metropolis: Past and Present, Vol IIB, p. 442.

- ^ ibid. Vol 1, p. 570.

- ^ Australian Places – Clifton Hill

- ^ "Melbourne's 321 suburbs ranked for liveability". Domain. 4 November 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ "Australian Dictionary of Biography". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 1993. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "Australian Dictionary of Biography". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 1993. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "Australian Dictionary of Biography". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 1993. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "Langridge, George David (1829–1891)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)