Sonnet 13

| Sonnet 13 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

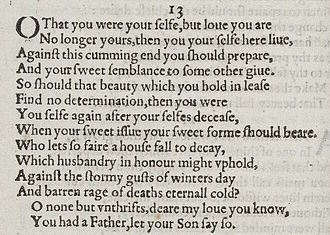

Sonnet 13 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 13 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a procreation sonnet within the Fair Youth sequence.

In the sonnet, the speaker declares his admiration and love for the beauty of youth, but warns this figure of youth that he will lose it if he doesn't revitalize himself through offspring. The primary arguments made in this procreation sonnet are the maintenance of self-identity and duty to one's own heritage. His tone throughout the sonnet is intimate, highlighting the theme of affection for youth that is prevalent in the first seventeen sonnets.

Paraphrase

[edit]The sonnet begins with the speaker expressing lament to youth with "O that you were yourself!" More simply, the speaker deplores that youth isn't absolute and permanent, and with "yourself", the speaker is referring to the figure of youth's soul. Following this, the speaker address the youth as "love", further developing the speaker's theme of adoration and personal affection for youth. From there, the speaker tells this youth that "you are / No longer yours, than you yourself here live", saying that the youth's identity is constantly fading away from him as he ages, as if he is unbecoming himself. With the lines "Against this coming end you should prepare / And your sweet semblance to some other give", the speaker is simply saying that the youth's life is slipping away day after day, and if he doesn't get married and have children, he will lose his identity to his death. Continuing from this idea, the speaker says "So should that beauty which you hold in lease / Find no determination; then you were / Yourself again after yourself's decease, / When your sweet issue your sweet form should bear", all meaning that whatever beauty the youth still has is only temporary (leased to him) and will be lost, unless he has children who continue the legacy and identity of his youthful beauty even after death. Continuing with "Who lets so fair a house fall to decay," the speaker refers to the youth as this "house" in reference to his fair body and his fair lineage. Adding to this, the speaker continues on with "Which husbandry in honour might uphold, / Against the stormy gusts of winter's day / And barren rage of death's eternal cold?". These lines suggest that by taking up marriage and becoming a husband and a father, the youth might be able to maintain his essence of youth against the devastations of time and age. This, the speaker compares to storms and winter, ending with the threat of the eternal nature of death, at which point the youth would be too late in renewing himself. In the ending couplet, the speaker mirrors his starting wail of lament in line 1 with "O! none but unthrifts. Dear my love, you know, / You had a father: let your son say so." Here, the speaker is separating the youth figure he adores from those he considers foolish, or "unthrifts", and connects that to the youth's inheritance, suggesting that only "unthrifts" would ignore their inheritance of life and youth and deny their own fathers' wish for continued lineage and legacy.

Context

[edit]Sonnet 13 is included as one of Shakespeare's Procreation sonnets. Sonnets 1-17 are an introduction to the plot of the complete sonnets. Each of these 17 sonnets is a different argument to convince the young man to marry a woman and have children to continue his legacy and to have his beauty live on.[2] In Sonnet 13, the poet uses his undying love for the young man as a motivator and as an encourager for the youth to marry a woman and eternalize his beauty by having children.[3]

The Sonnets collection is suspected to have been written during an unknown timeline of years beginning prior to 1598 and then more periodically from 1599 to 1609. 1609 is the year that the collection was finally published for the first time.[4] Shakespeare's book of sonnets is dedicated to "Mr. W.H.". There has been much academic speculation and conversation over who W.H. could be. One argument is that Anne Hathaway, the bride of Shakespeare, is the mysterious W.H. because of her masculine features. Another possibility is that W.H. could refer to Anne's brother, William Hathaway. The initials are appropriate for the dedication.

As expressed in Sonnet 104, the figure of youth to whom the sonnets are directed towards is hinted to be someone who has had of at least three years. In attempts to match Shakespeare's references of time and known relationships, of who this figure of youth (and also W.H) may be is William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, who Shakespeare may have dedicated his First Folio.[5] While the connection seems strong, it is only speculation. Sonnet 13 shows the increasing amount of love that the speaker holds for the man and is more intimate than the previous sonnets.[6] It is also the first of Shakespeare's sonnets where he refers to the young man as "Love" and "My dear love."

Structure

[edit]Sonnet 13 follows the same format as the other Shakespearean Sonnets. There are fourteen iambic pentameter lines and the rhyme scheme is ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. The rhyme scheme follows that of the 'English', or 'Surreyan', form of sonnet. After line 8 (the octave), there is a change of tone and fresh imagery.[7] This is shown when the speaker moves from speaking about the young man's loss of identity to age with words like "hold in lease" and "yourself's decease" before the end of the octave to speaking about the regenerative nature of husbandry and the duty to one's parents to continue the line with words such as "Who lets so fair a house fall to decay" and "dear my love you know: / You had a father; let your son say so."

Line eleven may be taken as an example of regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / Against the stormy gusts of winter's day (13.11)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The rhetorical volta or turn between line eight and nine is supported by the distinct rhythms of the two lines, which may be scanned:

× × / / × × / / × / When your sweet issue your sweet form should bear. / × × / × / / × × / Who lets so fair a house fall to decay, (13.8-9)

Here, the two instances of ictuses moved to the right tend to set a deliberate pace, whereas the following two instances of ictuses moved to the left suggest an abrupt rhythm.

Analysis

[edit]In Sonnet 13, for the first time, Shakespeare refers to the young man as "you" instead of his usual address of "thou", which he used in sonnets 1–12. This is more formal as thou, like the French "tu" is used for intimates and the use of "you" here is therefore at odds with the personal intensity toward this figure of youth . Its use could signify potential loss.[8][9]

The love that Shakespeare has for the young man has contradicting views in Sonnet 13. One aspect of love includes Shakespeare viewing the young man as a lover, or perhaps, as a personification of love itself.[10] In Line 1, the young man is referred to as "Love" and in Line 13 as "My Love", the first time these terms of endearment are used in the sonnet sequence.[11] These lines suggest an intimate, and possibly romantic relationship between the two men, though this piece focuses on the young man having children. A contradicting view of love occurs in Line 14, when Shakespeare states "You had a father; let your son say so". This final line from Sonnet 13 suggests that the love that Shakespeare had for the young man was a parental love, similar to one a father would have towards his son.[12]

The repetition of terms relating to death, like end, decease, decay, barren and unthrifts in contrast to the speaker's pleas to the figure of youth with terms like sweet, beauty, and husbandry highlight the poem's theme of having children in marriage to combat mortality's damages.[13] In 16th century conveyancing 'the determination of a tenancy' or 'the determination of a lease', its ceasing, occurred when the husbandman or leasee died without heirs and the use of the lands or estate fell again to the leasor. The poet here argues that, if the youth were to have sired children, then the beauty, at present leased to him, should on his death not find a "determination" or cessation, because heirs would exist to whom the lease of beauty could be bequeathed.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ^ Shakespeare, William, and David Alexander West. Shakespeare's Sonnets: With a New Commentary. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co, 2007. 6-7. Print.

- ^ Duncan Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York: AS, 2010. 100. Print

- ^ Duncan Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York: AS, 2010. 12. Print.

- ^ Larsen, Kenneth J. "Mr. W.H." Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2010). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Bloomsbury, New York. 136. Print.

- ^ Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2010). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Bloomsbury, New York. 96-97. Print.

- ^ Busse, Ulrich. Linguistic Variation in the Shakespeare Corpus: Morpho-syntactic Variability of Second Person Pronouns. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins Pub., 2002. 91. Print.

- ^ Shakespeare, William, and David Alexander West. Shakespeare's Sonnets: With a New Commentary. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co, 2007. 50. Print.

- ^ Mirsky, Mark J. The Drama in Shakespeare's Sonnets: "A Satire to Decay". Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson UP, 2011. 45. Print.

- ^ Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: Belknap of Harvard UP, 1997. 102. Print.

- ^ Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: Belknap of Harvard UP, 1997. 102. Print.

- ^ McGarrity, Maria. "The "Houses of Decay" and Shakespeare's "Sonnet 13": Another Nexus in "Proteus"" James Joyce Quarterly Fall 35.1 (1997): 153-55. JSTOR. Web. 17 Sept. 2014.

- ^ Larsen, Kenneth J. "Sonnet 13". Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Ingram, W.G., and Theodore Redpath, eds. Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1978. Print.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

[edit] Works related to Sonnet 13 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 13 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource