Sonnet 147

| Sonnet 147 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

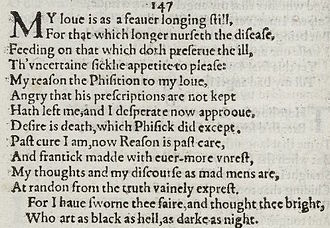

Sonnet 147 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 147 is one of 154 sonnets written by English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. Sonnet 147 is written from the perspective of a poet who regards the love he holds for his mistress and lover as a sickness, and more specifically, as a fever. The sonnet details the internal battle the poet has between his reason (or head) and the love he has for his mistress (his heart). As he realizes his love is detrimental to his health and stability, perhaps even fatal, the poet's rationality attempts to put an end to the relationship. Eventually, however, the battle between the poet's reason and his love comes to an end. Unable to give up his lover, the poet gives up rationale and his love becomes all consuming, sending him to the brink of madness.

Structure

[edit]Sonnet 147 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form abab cdcd efef gg and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 8th line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / Desire is death, which physic did except. (147.8)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Line 3 begins with a common metrical variant, an initial reversal:

/ × × / × / × / × / Feeding on that which doth preserve the ill, (147.3)

An initial reversal also occurs in line 6, and a mid-line reversal occurs in line 12. The 9th line exhibits a rightward movement of the fourth ictus (resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

× / × / × / × × / / Past cure I am, now reason is past care, (147.9)

The meter demands a few variant pronunciations: line 4's "the uncertain" functions as three syllables ("th'uncertain"), line 7's "desperate" as two;[2] and line 11's "discourse" (although a noun) is stressed on the second syllable.[3]

Context

[edit]As a piece within Shakespeare's sonnet collection, Sonnet 147 lies within the Dark Lady sonnets sequence (Sonnets 127-154), following the Fair Youth sequence (Sonnets 1-126).[4] Placed after the Fair Youth sonnets, which "celebrate a young male love object", The Dark Lady sonnets are associated with a woman of dark physical and moral features.[5] Unlike the Fair Youth sonnets, which refer lovingly and admirably to the beauty and person-hood of a young male, the Dark Lady sonnets frequently include harsh and offensive language, often including sexual innuendos, to describe a woman who is neither admirably beautiful, nor of admirable means or aristocratic status.[5] By writing about this dark and simple woman, Shakespeare writes in stark contrast to most poets of his time, who often and predominantly wrote about fair, virginal, young girls who were of high social status.[5] As with the questioned identity of the inspiration for the Fair Youth sonnets, the identity of the original Dark Lady has been disputed and argued for centuries. Unlike the Fair Youth sonnets, however, there is little academic "proof" to back up any proposed female muses, though historical characters ranging from Shakespeare's wife Anne Hathaway, Emilia Lanier, and even Queen Elizabeth herself have been suggested as potential femmes fatales.[6]

Critical explanation

[edit]Overview

[edit]Sonnet 147 reveals a paradox within the poet, and perhaps the population at large, between desiring the exact sin or ill which makes one sickly, unstable, or less completely whole as an individual, and knowing the thing you desire, in this case the poet's mistress, is the very thing causing trouble. Scholar Don Paterson, like many other Shakespearean scholars, has proposed this particular sonnet was in part inspired by an ending passage in The Old Arcadia written by Sir Phillip Sydney, which reads, "Sicke to the death, still loving my disease".[7]

Quatrain 1

[edit]The first quatrain of the sonnet lets the reader know the poet has been "infected", in a sense, by his mistress. Though the idea of being "love-sick" has been often idealized and romanticized in modern culture, the way the poet describes his lustfulness and want leads to a more dark reading, almost as if he is a host to some sort of sickly desired parasite feeding on his sense and reason. The poet begins the sonnet by linking and treating love and disease as parallel and intricately linked concepts.[8] The poet's mistress has planted a sickly fever within the poet, being a type of bodily love and desire, which is causing an illness within him.[9] His love/lust and wantonness is weakening him to the point where his lust has perhaps taken on its own sort of force and being, much as a fever does, and is now occupying a space in his body.[9] There also appears a never ending cycle, within the first two lines.[10] Carl Atkins points out that, "In this author 'longing still For that which longer nurseth the disease' is not idle wordplay, but suggests the patient's sense that this condition is never going to end". It is also important to note that the idea that the poet would "feed" his fever would have been quite contrary in Elizabethan England, as the going knowledge at the time was to never feed a fever, based on the Four Humours medical belief. The common idiom and medical belief of the times was to "feed a cold, starve a fever".[11]

Quatrain 2

[edit]His reason, which Shakespeare compares to the only knowledgeable "physician" or mind around, is the thing that offers him a way of easing its mad fever.[7] The poet's reason can't bear the fact the poet is so foolish and reckless with his body and mind, and abandons the poet entirely.[12] David West contends that "Abandoned and despairing, [the poet] he is proving by experience that desire is death."[12] A reader is left to assume without a doctor, reason, around, the ill and fever affecting the poet are doomed to take over completely, leaving death as the only possible outcome.[12] Shakespeare seems to accept this inevitable outcome and writes the final line of the quatrain saying "Desire is death". The final line of the quatrain may hint at a biblical allusion and reference Romans 8:6, where a very similar line appears stating, "For to set the mind on the flesh is death, but to set the mind on the Spirit is life and peace", correlating with the inference that the Dark Lady is morally dark as well as physically dark, and is darkening her lovers morals as well.[13]

Quatrain 3

[edit]In the final quatrain, the poet begins to describe his downfall and continuing/ worsening sickness. The line "Past cure I am, now reason is past care," is a play on an old proverb which is usually read "'past care, past cure' expressing the traditional wisdom, that, if a patient is incurable, care will not help him".[12] Many scholars have speculated what exactly the play on the common proverb means, since it is extremely unlikely Shakespeare misused a common and well known phrase. One could read the line as a potential marker for the madness the poet says is taking over his body, becoming so muddled and crazed with the fever, he can not even properly use a common saying.[12] Scholars W.G. Ingram and Theodore Redpath also propose, "Shakespeare is here not merely reproducing the proverb . . . but playing with it, for . . . he has here inverted it. The case is past cure, because the physician has ceased to care."[14] To further prove and point out the "frantic-mad" and "random "bablings" of the poet past cure and care, G. Blakemore Evans observes that "The poet's frenzied state of mind is illustrated by the harshly extreme indictment of his mistress in the following couplet."[15]

Couplet

[edit]Leading up to these lines, the poet has been merely describing his symptoms and craze to the reader. Once the couplet begins, however, the tone of the sonnet shifts and the poet begins to address his lady, and not fondly as most sonnets would. These final lines could in fact be more evidence for his madness; he has sworn the woman he desires as fair and bright, but is aware she is anything but, comparable only to sin and uncertainty.[12] David West observes that "The madness is defined in the last two lines, and 'fair . . . bright . . . black . . . dark' all contain moral meanings, The darkness is not simply the absence of light. It is the presence of evil."[12]

References

[edit]- ^ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ^ Booth 2000, p. 127.

- ^ Groves, Peter (2013). Rhythm and Meaning in Shakespeare: A Guide for Readers and Actors. Melbourne: Monash University Publishing. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-921867-81-1.

- ^ Duncan-Jones, Katherine (1997). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: A & C Black Publisherd Ltd. p. 46.

- ^ a b c Duncan-Jones, Katherine (1997). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: A & C Black Publishers Ltd. p. 47.

- ^ Duncan-Jones, Katherine (1997). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: A&C Black Publishers Ltd. p. 50.

- ^ a b Paterson, Don (2010). Reading Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: Faber and Faber. p. 455.

- ^ Alden, Raymond MacDonald (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 358.

- ^ a b Duncan-Jones, Katherine (1997). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: A&C Black Publishers. pp. 410–411.

- ^ Atkins, Carl (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Danvers, Massachusetts: Rosemont Publishing. pp. 447–448.

- ^ Atkins, Carl (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three-Hundred Years of Commentary. Farleigh Dickins University Press. pp. 360–361.

- ^ a b c d e f g West, David (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London, Woodstock, New York: Duckworth Overlook. p. 448.

- ^ Booth, Stephen (1997). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Westford, Massachusetts: Yale University Press. pp. 518–19.

- ^ ed. Ingram and Redpath, W.G., Theodore (1964). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London, England. p. 520.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Blakemore, G. Evans (1996). The Sonnets. Great Britain: Cambridge University Press. p. 267.

Further reading

[edit]- McNeir, Waldo F. "The Masks of Richard the Third." SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 11.2. (1971): 167–186. Print.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.