Mary Sutton, Countess of Home

Mary Sutton | |

|---|---|

| Countess of Home | |

| Born | 2 October 1586 |

| Died | 1644 |

| Spouse(s) | Alexander Home, 1st Earl of Home |

| Issue | James Home, 2nd Earl of Home Margaret Home, Countess of Moray Anne Home, Countess of Lauderdale |

| Father | Edward Sutton, 5th Baron Dudley |

| Mother | Theodosia Harington |

Mary (Dudley) Sutton, Countess of Home (1586–1644), was a landowner, living in England and Scotland.

Early years and marriage

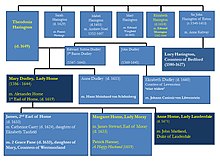

Mary (Dudley) Sutton, born 2 October 1586, was the eldest daughter of Edward Sutton, 5th Baron Dudley (d. 1643) and his wife Theodosia Harington (d. 1649), youngest daughter of Sir James Harington. The title "Dudley" and surname "Sutton" were interchangeable.[1]

Little is known about her childhood, and there were problems in the family because her father had abandoned her mother for Elizabeth Tomlinson. In 1597 her younger brother Ferdinando and her sister Anne were lodged in Clerkenwell, as wards of their aunt Elizabeth Harington and uncle Edward Montagu of Boughton.[2] Lord Dudley was ordered to pay her £20 yearly by the Privy Council, but refused to pay.[3]

Later, Lady Anne Clifford described Mary as her childhood companion, "my old companion" and "my old acquaintance", and said their mothers had been friends.[4] After the Union of the Crowns in 1603, her mother Theodosia Harington seems to have been an important member of Princess Elizabeth's household and before their marriage in London, Frederick V of the Palatinate gave her a valuable gift of silver plate.[5]

Her sister Anne Dudley (d. 1615) married Hans Meinhard von Schönberg and was the mother of Friedrich Hermann von Schönberg. Anne Dudley bequeathed to Lady Home, "a little ring made in the fashion of a heart enameled black with a little diamond".[6] Anne Dudley was a lady in waiting to Princess Elizabeth (known as Mistress Dudley), as was her cousin Elizabeth Dudley, Countess of Löwenstein, daughter of her uncle John Dudley, both appointed to the royal household because of their Harington family connection. It is likely that the Countess of Home would later be an advocate for the cause of the Elizabeth of Bohemia in England and Scotland.[7]

Her youngest sister, Margaret Dudley (1597-1674) married Miles Hobart of Plumstead (born 1602) in 1627 at St Ann Blackfriars, London. He was a son of Thomas Hobart of Plumstead and Willoughby Hopton, a daughter of Arthur Hopton of Blythburgh and Witham. According to Lady Home's lawyer, they lived 7 miles inland from Yarmouth. In later years Theodosia Dudley moved to Norfolk to be near her daughter at Beeston.[8]

On 11 July 1605 Mary married the wealthy Scottish widower Alexander Home, 1st Earl of Home (died 1619), a marriage perhaps arranged by James VI and I and intended to effect the Anglicization of Scottish aristocracy. The newly created title of Earl of Home was counted in 1605 as a title in the English peerage.[9] The wedding was celebrated by Peter Alibond, vicar of St Michael's, Chenies, at Bedford House in the Strand in the presence of her cousin Lucy Russell (née Harington), Countess of Bedford, with Bedford's usher John Stewart, Winifred Barnes, Captain Thomas Tyrie, and James Congleton.[10] King James gave her an annual pension of £300, which she resigned in 1617.[11] The Countess of Home frequently travelled to London. In June 1616 Anne Clifford recorded meeting her at the house of her cousin Lucy, Countess of Bedford.[12]

Celebrating an Anglo-Scottish marriage

The couple had a historical connection; her grandfather Edward Sutton, 4th Baron Dudley had been the keeper of Hume Castle in the Scottish borders which had been captured from Alexander Home's grandmother, Mariotta Haliburton in 1548.[13] This link was celebrated at King James's arrival at Dunglass Castle on 13 May 1617.[14] The poet David Hume of Godscroft wrote a Latin verse to be said on this occasion which contrasted Mary's rebuilding of the earl's houses with the destruction wrought by her grandfather during the war of the Rough Wooing. He refers to the improving work of her English hand;

Mentiar; aut nullis horrendam ducimus Anglam,

Judice te; vultum respice, sive animum.

Nec fera miscemus, truculento, proelia, Marte:

Sed colimus, casti, foedera sancta, thori.

Hinc surgunt mihi structa palatia, diruit Angla

Quae quondam, melior iam struit Angla manus:

Hinc quam fausta tibi procederet UNIO, si sic

Exemplo, saperes Insula tota, meo.[15]

Either I'm a liar, or we think that an Englishwoman is not terrible in any respect, as you judge: just consider her countenance or her mind. Nor shall we join battles in cruel war, but rather we are observing the sacred laws of a chaste marriage. Hence a castle, built for me, which an English hand had once demolished, a better English hand is now rebuilding. Hence this union will go prosperously for you and your entire island, if you grow wise after my example.[16]

Life as a widow

Alexander, Earl of Home died on 5 April 1619 in London in a house in Channel Row. Anne Clifford and the Countess of Bedford visited Lady Home there on 19 April.[17] Lady Home was left wealthy, and it was rumoured the king gave her £1200 in June,[18] but she had to defend her young son's rights as Earl of Home as owner of large estates in Berwickshire and the Scottish Borders, with the help of his guardians and curators, and leading members of the Home family.

Abraham Hume, a recent graduate of St Andrews University, was her chaplain around the year 1630, and he is said to have composed "remarks" objecting to London life and public affairs based on his experience of the Caroline court with his patron. Hume was subsequently chaplain to her son-in-law, John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale, then called Lord Maitland, and accompanied him on a Grand Tour.[19]

Thomas Hope of Craighall

The Countess of Home employed the lawyer Sir Thomas Hope of Craighall and he recorded some details of her business in his diary. On Tuesday 1 April 1634 she came to his lodging in Edinburgh with her family, the Earl of Lauderdale, John, Lord Maitland, James, Lord Doune and his wife, her daughter Margaret Lady Doune. They offered him 2,000 merks as an inducement in a legal process.[20] Hope noted that she spoke to him first apart from the others, but offered £2,000 Scots as if she were unfamiliar with Scottish money.[21]

Coldingham Priory and the Hirsel

She disputed the ownership of lands of Coldingham Priory, and particularly the Northfield of Coldingham and the teinds of Auldcambus and Fast Castle, with Francis and John Stewart, sons of Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell before the Privy Council of Scotland in 1620 and the issue continued in following years with interventions from James I and Charles I.[22]

The house and estate at the Hirsel was part of the lands of Coldstream Priory. William Ker, a younger brother of John Ker of Littledean, wrote to Francis Stewart, son of the Earl of Bothwell about the Priory lands in July 1632. According to Ker, Coldstream had been obtained by the crown lawyer Thomas Hamilton, Earl of Haddington. He worked to Lady Home's benefit regarding the teinds of the Hirsel estate during her son's minority. Ker described their interaction as collusion. He hoped that Sir Robert Ker could agree with the young Earl of Home about details of the Hirsel estate.[23]

Cockburnspath

On 14 August 1634, she contracted with John Arnot, the postmaster of Cockburnspath near Dunglass castle that he would repair and rebuild the teind barn and barnyard of Cockburnspath and keep it in good order and have the use of it for 20 merks yearly, allowing her servants to use the barn to stack her teinds. Lady Home paid the minister's stipend at Cockburnspath, in 1638 the minister was George Sydserf.[24]

A loan for the Scottish army

In May 1644, the Countess of Home was able to lend £7,300 sterling towards the expenses of the Scottish Covenant army in Ireland. The merchant financier Robert Inglis accepted the loan and its equivalent in gold was sent to Carrickfergus. The soldier Sir John Ruthven was involved in this transaction.[25]

Many sundry particular things

Mary maintained houses in London and in Edinburgh, employing Nicholas Stone and Isaac de Caus to work on her house in Aldersgate, which was later known as Lauderdale House.[26] This house was used by the Spanish ambassador Carlos Coloma in October 1635.[27] She built a summerhouse at Twickenham Park and decorated it with blue gilt leather recycled from her Scottish houses. At Highgate she extended an existing house, obtained from the queen's silkman William Geere, which survives and is known as Lauderdale House.[28]

In Edinburgh she rebuilt the house in the Canongate now called Moray House, employing the master mason William Wallace and the painter John Sawers.[29] She had two sets of chairs made in London in the latest Italianate fashion. There was a suite of three garden vault rooms with a black marble banqueting table.[30] A gallery room was furnished with a couch bed and hung with at least 30 pictures.[31] There was a balcony at the back of the house, overlooking the garden.[32]

The garden included terraces, a mount, walks and wilderness, and two summerhouses. She had cherry, plum, apple, apricot, fig, and damson trees. Lady Home wrote an 8-point list of conditions for the employment of her gardeners, John Simpson and Christopher, forbidding them to sell any garden produce. She owned a copy of John Parkinson's Herbal,[33] an influential work by an apothecary and botanist who supplied plants to Charles I and Henrietta Maria.[34] With her cousin Lucy, Countess of Bedford, she can be associated with the artist Nathaniel Bacon who painted still lifes of fruit and vegetables, and a network of women connected with the court who were enthusiastic fruit growers, including Alethea Howard, Countess of Arundel at Tart Hall.[35] In February 1633, the Earl of Morton obtained her permission for the house to be at the disposal of Charles I during his visit and coronation in Scotland, but the plan was cancelled due to the death of her son.[36]

She kept detailed inventories of her houses which record purchases made in London, listing beds, tapestries, and her books including volumes of sermons and a work penned by Esther Inglis.[37] She had distilling equipment, loadstones, telescopes, a weather glass, and bronzes by Francesco Fanelli. She listed paintings by subject and noted that some were bought from George Geldorp, others from the New Exchange, many with religious subjects including the Nativity and Christ and the Samaritan Woman. She acquired items with Harrington knot heraldry from the sale of the effects of her cousin the Countess of Bedford, and a set of silver candleholders that had belonged to Marie de' Medici, mother of Henrietta Maria.[38][39]

These inventories include notes she wrote for her housekeepers and their written replies which form short dialogues. Lady Home wrote of an unsatisfactory inventory that it;

"has byn wildely tacken in & are no way to bee trusted tow for comparein them with my own little book. I find in some roomes that neather in theare notes of what they say wants nor in that they say restes will bothe make up togeather which is sayde to bee in my booke of maney sondre partikeulor thinges."[40]

The housekeeper at Floors near Kelso,[41] Jane Descheil, was married to the coachman, she paid cleaners, fed the cat and the turkeys, brewed ale, made honey, bleached cloth, supervised a carpenter mending buffet stools, and sewed a featherbed, while Lady Home was away. At Twickenham Park, the housekeeper Judith Plummer was the wife of the gardener, and she embroidered shadow work on a bedsheet which the Countess treasured. A letter from Dorothy Spence, the Canongate housekeeper, was intercepted in 1645 and printed in a Royalist pamphlet. The male servants and the gardeners mentioned in surviving papers were all paid less than these female housekeepers. Food was bought in Edinburgh by the butler James Simpson. A servant Adam Young had a room in Edinburgh but also witnessed contracts in London.[42]

In the 1630s and 1640s it became fashionable to own free-standing trompe d'oeil portraits of servants, family members, and children, now called "dummy boards".[43] Lady Home had some of these made and painted for her in London. These included a shepherdess, a chamber maid, a man playing a viol, and a drawing chamber at the Canongate near her daughter Lady Doune's nursery overlooking the garden was inhabited by three "standing picktours" representing her two grandchildren and their attendant, the dwarf Meg Candie.[44]

Nicholas Stone

In 1638 she discussed the design of a tomb in white and black marble for her family to be built at Dunglass with Nicolas Stone in person at his workshop in Long Acre, which was not executed.

... my will is to have the tombe made with our pictures to the waist in white marble and three through stones to be laid upon us, I, my lord, my dear son Home and my selfe, & I would be laid betwixt them, & so my picture sett, Mr Stone the stone cutter that dwells in Long Acre showed me a tombe he had made for a knight & his wife in that maner ...[45]

Dunglass Castle was destroyed by an explosion in August 1640 and among the fifty two dead was John White, an English plasterer who also worked for her at The Hirsel, and at Winton House for George Seton, 3rd Earl of Winton.[46] She sold Twickenham Park that year.

Family and legacy

Marriages of her son, James Home

In May 1622 at Whitehall Palace her son James, Earl of Home, married Catherine Cary daughter of Henry Cary, 1st Viscount Falkland (c.1575 – 1633) and Elizabeth Cary née Tanfield. John Chamberlain noted that the marriage had been arranged by the king.[47] In Scotland, before the wedding, following the king's instructions, the lawyer Thomas Haddington convened a meeting of the six lairds of the Home surname to tell them about the marriage plans. They promised to help the earl, but had reservations, hoping that Lady Home would "make her intentions and courses known to them" and she would "hear and respect their faithful advice" concerning the earl, and if she neglected to consult them, they could have "no contentment in the business."[48] In December, Lady Home wrote to Leonard Welstead, an agent of Lord Falkland (and formerly, with Matthew Lister, a trustee of the Countess of Pembroke), about dowry payments, and the toothache suffered by Lord Home and Catherine.[49]

After Catherine's death in childbirth in 1625, James married Grace Fane, daughter of Francis Fane, 1st Earl of Westmorland (1583/4–1629).[50] James still had legal guardians called "curators" including the Earl Marischal, the Earl of Morton, and Sir Robert Kerr of Ancram, a gentleman in the king's bedchamber. Mary wrote to Morton (who was in England) for help over dowry payments, wanting an installment of £1000 Sterling cash sent to her in Scotland rather than allow the Earl of Westmorland to invest the money in a project in England and buy land. She hoped the rest of the curators would agree with her, deferring to their "wiser judgements" but insisting "I will bee the last consentor to such a bisnes". She wanted the cash for dowries for her daughters.[51]

Mary Mildmay Fane, Countess of Westmorland wrote letters to her daughter Grace in Scotland solicitous of her health, including passages in cipher, one referring to loss of her hair through illness. She hoped Grace would come to London to take her sisters to see the masques at court in 1631, Love's Triumph Through Callipolis and Chloridia. Grace was treated by an Edinburgh physician, David Arnot. James Home died in London in February 1633, attended by the court physician Théodore de Mayerne,[52] and Grace died soon afterwards at Apethorpe. The two countesses continued a bitter lawsuit over their children's properties. Westmorland was her daughter's executrix. She complained that the Countess of Home had the advantage in Scottish courts from her continual residence and acquaintance in Edinburgh.[53] Charles I wrote to the Court of Session in Westmorland's favour on 5 May 1634.[54]

The earldom passed to a distant cousin James Home, 3rd Earl of Home (1615–1666). Mary wrote to Sir David Home of Wedderburn from Aldersgate after her son's death about the future of the Home family, name, and "ancient raice", asking him to "express your love both to the living and to the dead".[55]

Lady Moray and Lady Lauderdale

A Scottish author Patrick Hannay (fl. 1616–1630) dedicated A happy husband or, Directions for a Maide to choose her Mate, As also, a Wives behaviour towards her Husband after Marriage (Edinburgh, 1618/1619?) to Mary's eldest daughter Margaret Home (d. 1683), who married James Stewart, 4th Earl of Moray in 1628. Hannay's title refers to Sir Thomas Overbury.

In 1632 Mary's younger daughter Lady Anne Home married John Maitland later Duke of Lauderdale. Anne inherited her mother's properties and furnishings in London.

Lady Home's will

Mary made a will in 1638 reflecting her English and Scottish properties and identity. She hoped her granddaughters would inherit her furnishings and collection, dividing house contents in London and Scotland between them, according to the inventories of each house. She was aware that this was problematic, writing "And I am not ignorant that my houses both in Edinborough as Canongate and in Aldersgate Street being inheritance I cannot dispose so of them by this my late will neither by the laws of England nor Scotland". Amongst personal bequests to her family and servants, she left a purse of gold coins to her nephew, Frederick Schomberg, 1st Duke of Schomberg, the son of her sister Anne (Dudley) Sutton. The will appointed her granddaughter Lady Mary Stewart (d. 1668) as executor, but she was still a minor when the countess died in London in March 1644. Her body was shipped to Scotland and buried at Dunglass. Her daughters and their husbands instead acted as executors and "administratices". An account of the financial settlement to 31 March 1646 was made by the merchant financier Robert Inglis.[56]

The will and the Commonwealth

In 1648 Lauderdale's share of her possessions and furniture in London was forfeited by his delinquency and sold. Claims that the furnishings belonged to his daughter or had been sold to a Scottish merchant in London, Robert Inglis, were disregarded. Some goods at Aldersgate were sold in October 1648. It also came to light that Mary had lent £2,000 to the Earl of Cleveland and obtained property in Hackney and Stepney, and £1000 to Elizabeth Ashfield, a neighbour in Aldersgate, gaining her lands at North Barsteed in Suffolk.[57] A challenge to the administration of the will by a third-party William Dudley, demonstrating that goods belonged not to Lauderdale but to his daughter, and that the executors had not been lawfully appointed, failed in 1658. Lauderdale was enabled to recover his property at the Restoration. It is due to the complexities of dividing her goods and this legal battle that her inventories survive to give a unique insight into the material culture of Anglo-Scottish aristocrat in the 1630s.[58] The inventories include a set of portraits after Van Dyck now at Darnaway Castle.[59]

Children

Lady Home had seven children, all of whom were born in Scotland attended by Mrs Cuthbert, an English midwife.[60] Three reached adulthood; James, Margaret and Anne. One child was born in Scotland in October 1612. Anne of Denmark sent instructions to the chamberlain of her Dunfermline estates, Henry Wardlaw of Pitreavie, to distribute presents of money at the christening, and Anna Hay, Countess of Winton was to be her representative. The child was probably Anne, the queen's namesake.[61][62][63] The Earl of Home was a Catholic, and in December 1615 the Archbishop of St Andrews objected to his choice of tutor for his children.[64]

- James Home, 2nd Earl of Home (d. 1633) who married firstly, Catherine Cary (1609–1626) eldest daughter of Viscount Falkland and the playwright Elizabeth Tanfield Cary author of The Tragedy of Mariam.[65] In 1626 James married Grace Fane (d. 1633) daughter of Francis Fane, 1st Earl of Westmorland and Mary Mildmay.

- Margaret Home, Countess of Moray, who married James Stuart, 4th Earl of Moray, and lived at Donibristle.

- Anne Home, Countess of Lauderdale (d. 1671), who married John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale. Their daughter Mary Maitland married John Hay, 2nd Marquess of Tweeddale.

References

- ^ Henry Sydney Grazebrook, 'An Account of the Barons of Dudley', Collections for a History of Staffordshire, vol. 9 (1880), p. 113

- ^ Acts of the Privy Council, vol. 27, pp. 325-8: ‘DUDLEY, alias SUTTON, Edward (1567-1643), of Dudley Castle, Staffs.' The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1558-1603, ed. P.W. Hasler, 1981.

- ^ Lamar M. Hill, 'The Privy Council and Private Morality', Charles Carlton, State Sovereigns & Society in Early Modern England (Stroud: Sutton, 1998), 212.

- ^ Jessica L. Malay, Anne Clifford's Autobiographical Writing, 1590-1676 (Manchester, 2018), pp. 39, 80, 86.

- ^ Nadine Akkerman, Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts (Oxford, 2022), p. 72.

- ^ Will of Maria Soton, Countess of Home.

- ^ Nadine Akkerman, The Correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart Queen of Bohemia, vol. 2 (Oxford, 2011), p. 1119.

- ^ Visitation of Norfolk in 1563, vol. 2 (Norwich, 1895), pp. 74, 111: Sir Thomas Hope's Diary (Edinburgh, 1843), p. 195.

- ^ Keith Brown, 'The Scottish Aristocracy, Anglicisation and the Court, 1603-1638', The Historical Journal, 36:3 (September 1993), pp. 543-576, 546, 551-2.

- ^ British Library, Stowe MS 574 f.66v

- ^ Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, vol. 11 (Edinburgh, 1894), p. 530, 712-3.

- ^ K. Acheson, Ann Clifford: The Memoir of 1603 and the Diary of 1616-1619 (Broadview, Toronto, 2007), pp. 91-3, 165, 167.

- ^ Grafton's Chronicle: A Chronicle at Large, 1569, vol. 2 (London, 1809), p. 503.

- ^ Roger Green, 'The King Returns: The Muses Welcome', Steven J. Reid & David McOmish, Neo-Latin Literature and Literary Culture in Early Modern Scotland (Brill, 2017), pp. 129-130, 134-5.

- ^ The Muses Welcome to the High and Mightie Prince James (Edinburgh, 1618).

- ^ Text translated for The Philological Museum by Dana F. Sutton

- ^ Jessica L. Malay, Anne Clifford's Autobiographical Writing, 1590-1676 (Manchester, 2018), pp. 80-1.

- ^ Thomas Birch & Folkestone Williams, Court and Times of James the First, vol. 2 (London, 1849), p. 172.

- ^ Edmund Calamy, An Abridgement Of Mr. Baxter's History Of His Life And Times, vol. 2 (London, 1713), pp. 511-2.

- ^ David Matthew, Scotland under Charles I (London, 1955), p. 73.

- ^ A Diary of the Public Correspondence of Sir Thomas Hope of Craighall, 1633–1645: From the Original, in the Library at Pinkie House (Bannatyne Club: Edinburgh, 1843), p. 10.

- ^ The Melros Papers vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1837), pp. 370-2, 550-1: The Earl of Stirling's register of royal letters, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1885), pp. 123, 329, 392: James Maidment, Letters and Papers of James the Sixth, pp. 324-8.

- ^ James Maidment, Analecta Scotica (Edinburgh, 1837), pp. 66-9.

- ^ Hirsel Documents, NRAS 859 box 17 bundle 2.

- ^ Mary Anne Everett Green, Calendar of the Proceedings of the Committee for Compounding, 1 (London, 1889), pp. 4–5, 10: TNA SP 46/106 ff. 99-104: Daniel Wilson, Memorials of Edinburgh, 2 (Edinburgh, 1848), p. 74: Robert Chambers, Traditions of Edinburgh (Edinburgh, 1869), p. 327.

- ^ W. G Spiers, 'Account Book of Nicolas Stone', 7th Volume of the Walpole Society (Oxford, 1919), p. 117.

- ^ John Bruce, Calendar State Papers, Domestic, 1635 (London, 1865), no. 29.

- ^ Osmund Airy, The Lauderdale papers, vol. 2 (London, 1885), p. 203

- ^ Nick Haynes & Clive B. Fenton, Building Knowledge, An Architectural History of the University of Edinburgh (Edinburgh, 2017), pp. 236-9, 237-8: Moray papers NRAS 217, 5:8 p. 15.

- ^ Marilyn M. Brown & Michael Pearce, 'The Gardens of Moray House, Edinburgh', Garden History 47:1 (2019), p. 7.

- ^ Antonia Laurence Allen, 'Trading Spaces', Pamela Bianchi, Displaying Art in the Early Modern Period: Exhibiting Practices and Exhibition Spaces (Routledge, 2023).

- ^ Marilyn M. Brown & Michael Pearce, 'The Gardens of Moray House, Edinburgh', Garden History 47:1 (2019), p. 48.

- ^ Marilyn M. Brown & Michael Pearce, 'The Gardens of Moray House, Edinburgh', Garden History 47:1 (2019), p. 5.

- ^ Rufus Bird, Simon Thurley, Michael Turner, St James's Palace: From Leper Hospital to Royal Court (Yale, 2022), pp. 47–48.

- ^ Joan Thirsk, Food in Early Modern England (London, 2007), pp. 296-7.

- ^ Marilyn M. Brown & Michael Pearce, 'The Gardens of Moray House, Edinburgh', Garden History 47:1 (2019), pp. 1-17.

- ^ Marie-Louise Coolahan & Mark Empey, 'Women's Book Ownership and the Reception of Early Modern Women's Texts', in Leah Knight, Micheline White, Elizabeth Sauer, Women's Bookscapes in Early Modern Britain: Reading, Ownership, Circulation (Michigan, 2018), pp. 234, 238.

- ^ Michael Pearce, 'Approaches to Inventories' in Architectural Heritage, 26 (Edinburgh, 2015), pp. 76-77: NRAS 217 box 5 no. 5.

- ^ Pearce, Michael (2016). Vanished comforts: locating roles of domestic furnishings in Scotland 1500-1650 (PhD thesis). University of Dundee., Appendix.

- ^ Michael Pearce, 'Approaches to Inventories' in Architectural Heritage, 26 (Edinburgh, 2015), pp. 76-77. doi:10.3366/arch.2015.0068

- ^ Old Floors or "Freres" was on a different site to the present castle, Daniel Kemp, Tours in Scotland by Richard Pococke (SHS: Edinburgh, 1887), p. 329.

- ^ Letters from the Marquess of Argyle .. & friends at Edinburgh (Oxford 1645), p. 8: NLS Tweeddale Papers, Home executry: NRAS 217, box 5 nos. 5, 8: NRAS 859, bundle 17/2.

- ^ Tara Hamling & Catherine Richardson, A Day at Home in Early Modern England: Material Culture and Domestic Life, 1500-1700 (Yale, 2017), pp. 227-8.

- ^ Moray Papers, Countess of Home inventories NRAS 217 box 5 no. 5.

- ^ Will of Maria Soton, Countess of Home, TNA Prob/11/272/611 ff. 403-6, and NLS MS. 14547.

- ^ William Lithgow, A briefe and summarie discourse upon that lamentable and dreadfull disaster at Dunglasse. Anno 1640 (Edinburgh, 1640): HMC 2nd Report: Forbes-Whitehaugh (London, 1871), p. 199.

- ^ Norman Egbert McClure, The Letters of John Chamberlain, vol. 2 (Philadelphia, 1939), p. 437.

- ^ The Melros Papers, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1837), pp. 403-4.

- ^ Richard Simpson, The Lady Falkland, Her Life. From a MS. in the Imperial Archives at Lille (London, 1861), p. 129.

- ^ Barbara Kiefer Lewalksi, Writing Women in Jacobean England (Cambridge, Mass, 1993), pp. 184-5: Meikle (2008).

- ^ The Home/Fane marriage contract is held at Northampton Record Office and letters from Mary Sutton at the National Library of Scotland, Morton Papers MS 80/2.

- ^ Marilyn M. Brown & Michael Pearce, 'The Gardens of Moray House, Edinburgh', Garden History 47:1 (2019), p. 6.

- ^ Calendar State Papers Domestic, Charles I: 1635, vol. 8, p. 610: TNA SP14/305 f.210.

- ^ Earl of Stirling's Register of Royal Letters Relative to the Affairs of Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1885), p. 737.

- ^ HMC Milne Home of Wedderburn Castle (London, 1902), p. 98 no. 219, the letter was written by her Scottish secretary.

- ^ Marilyn M. Brown & Michael Pearce, 'The Gardens of Moray House, Edinburgh', Garden History 47:1 (2019), p. 46, citing 'Will of Maria Soton, Countess of Home', TNA Prob/11/272/611 ff. 403-6: NLS MS. 14547: NRAS 217 box 5 no. 278

- ^ Calendar of the Proceedings of the Committee for Advance of Money, 1642-1656, part 2 (London, 1888), p. 948-952, the National Library of Scotland holds related papers and charters from the archive of the Tweeddale archive, including the Lauderdale's marriage contract, and the executry papers MS 14547.

- ^ Marilyn M. Brown & Michael Pearce, 'The Gardens of Moray House, Edinburgh', Garden History 47:1 (2019), p. 5.

- ^ Karen Hearn, Van Dyck & Britain (Tate: London, 2009), p. 178.

- ^ Will of Maria Soton, Countess of Home, TNA Prob/11/272/611 ff. 403-6, and NLS MS. 14547.

- ^ John Fernie, A History of the Town of Dunfermline (Dunfermline, 1815), p. 105

- ^ Claire Robinson, 'A Pair of Early Seventeenth-Century Gauntlet Gloves given by King Charles I to Sir Henry Wardlaw', Costume, 49:1 (2015), pp. 9, 13

- ^ Letter of Anne of Denmark to Henry Wardlaw, St Andrews University Library MS 38590

- ^ Original Letters Relating To The Ecclesiastical Affairs of Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club, 1851), p. 461.

- ^ Barbara Kiefer Lewalski, Writing Women in Jacobean England (Cambridge MA, 1993), 184-5, 189: N. E. McClure, Letters of John Chamberlain, vol. 2 (Philadelphia, 1939), 437, noting her name as 'Anne' rather than 'Catherine'.