Ira Aldridge

Ira Aldridge | |

|---|---|

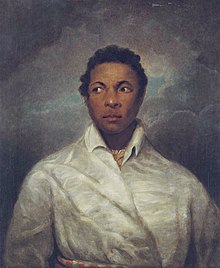

Portrait of Aldridge by James Northcote, 1826 | |

| Born | July 24, 1807 New York City, United States |

| Died | August 7, 1867 (aged 60) Łódź, Poland |

| Burial place | Old Łódź Cemetery, Poland |

| Citizenship | United States, United Kingdom |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, playwright |

| Years active | 1820s–1867 |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | Ira Daniel, Amanda, Ira Frederick, Luranah, Rachael |

Ira Frederick Aldridge (July 24, 1807 – August 7, 1867) was an American-born British actor, playwright, and theatre manager, known for his portrayal of Shakespearean characters. James Hewlett and Aldridge are regarded as the first Black American tragedians.

Born in New York City, Aldridge's first professional acting experience was in the early 1820s with the African Grove Theatre troupe. Facing discrimination in America, he left in 1824 for England and made his debut at London's Royal Coburg Theatre. As his career grew, his performances of Shakespeare's classics eventually met with critical acclaim and he subsequently became the manager of Coventry's Coventry Theatre Royal. From 1852, Aldridge regularly toured much of Continental Europe and received top honours from several heads of state. He died suddenly while on tour in Poland and was buried with honours in Łódź.

Aldridge is the only actor of African-American descent honoured with a bronze plaque at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. Two of Aldridge's daughters, Amanda and Luranah, became professional opera singers.

Early life and career

Aldridge was born in New York City to Reverend Daniel and Luranah (also spelled Lurona) Aldridge on July 24, 1807, but a few early biographies state that he was born in Bel Air, Maryland. At the age of 13, Aldridge went to the African Free School in New York City, established by the New-York Manumission Society for the children of free black people and slaves. They were given a classical education, including English grammar, writing, mathematics, geography, and astronomy.[1] His classmates at the school included James McCune Smith, Alexander Crummell, Charles L. Reason, George T. Downing, and Henry H. Garnet.[2]

Aldridge's first professional acting experience was in the early 1820s with the African Company, a group founded and managed by William Henry Brown and James Hewlett. In 1821, the group built the African Grove Theatre, the first resident African-American theatre in the United States.[3] The short-lived company was the subject of protests by neighbors, attacks by a rival company, and a racist parody by the Sheriff of New York. The Sheriff of the time was also a newspaper publisher, making it clear that Aldridge's career prospects in America were dim at best.[4] Aldridge made his acting debut as Rolla, a Peruvian character in Richard Brinsley Sheridan's Pizarro. He may have also played the male lead in Romeo and Juliet, as reported later in an 1860 memoir by his schoolfellow, Dr. James McCune Smith.[5]

Confronted with the persistent discrimination which black actors had to endure in the United States, Aldridge emigrated to Liverpool, England, in 1824 with actor James Wallack. During this time the Industrial Revolution had begun, bringing about radical economic change that helped expand the development of theatres.[5] The British parliament had abolished slavery in the UK in the 11th century, had outlawed the Atlantic slave trade and was moving toward abolishing slavery in the British Empire, which increased the prospect of black actors from abroad looking to perform.[6]

Having limited onstage experience and lacking popular recognition, Aldridge concocted a story of his African lineage, claiming to have descended from the Fulani princely line.[3] By 1831,[7] Aldridge had temporarily taken the name of Keene, a homonym for the then popular British actor, Edmund Kean. Aldridge observed a common theatrical practice of assuming an identical or similar name to that of a celebrity in order to garner attention. In addition to being called F. W. Keene Aldridge, he would later be called African Roscius, after the famous Roman actor of the first century BCE.[6]

In May 1825, at the age of 17, Aldridge first appeared on the London stage in a low profile production of Othello.[4] On October 10, 1825, Aldridge made a much more high-profile debut at London's Royal Coburg Theatre, and became the first African-American actor to establish himself professionally in a foreign country. He played the lead role of Oroonoko in The Revolt of Surinam, or A Slave's Revenge; this play was an adaptation of Thomas Southerne's Oroonoko (itself adapted from Aphra Behn's original work).[5]

According to the scholar Shane White, British theatre audiences had heard of New York's African Theatre because of actor and comedian Charles Mathews.[8] Mathews had recently produced a popular comedic lampoon of what he imagined the African Theater was like (he had never actually been).[4] Bernth Lindfors stated:

[W]hen Aldridge starts appearing on the stage at the Royalty Theatre, he's just called a gentleman of color. But when he moves over to the Royal Coburg, he's advertised in the first playbill as the American Tragedian from the African Theater New York City. The second playbill refers to him as "The African Tragedian". So everybody goes to the theater expecting to laugh because this is the man they think Mathews saw in New York City.[6]

An innovation Aldridge introduced early in his career was a direct address to the audience on the closing night of his engagement at a given theatre. Aldridge would speak to the audience on a variety of social issues which affected the United States, Europe and Africa. In particular, Aldridge spoke on his pro-abolitionist sentiments, for which he was widely celebrated.[3]

Critical reception

During Aldridge's seven-week engagement at the Royal Coburg, the young actor starred in five plays. He earned admiration from his audiences while critics emphasized Aldridge's lack of formal stage training and experience. According to modern critics Errol Hill and James Vernon Hatch, early reviews were mixed. For The Times he was "baker-kneed and narrow-chested with lips so shaped that it is utterly impossible for him to pronounce English"; The Globe found his conception of Oroonoko to be very judicious and his enunciation distinct and sonorous; and The Drama described him as "tall and tolerably well proportioned with a weak voice that gabbles apace."[5] The Times critic also found fault with Aldridge's "copper" complexion, considering it insufficiently dark for Othello.[10] Meanwhile, The Athenaeum magazine was scandalized by a black man with white actresses, and the paper Figaro in London sought to "drive him from the stage" because of his color.[4]

Aldridge performed scenes from Othello that impressed reviewers. One critic wrote, "In Othello [Aldridge] delivers the most difficult passages with a degree of correctness that surprises the beholder."[11] He gradually progressed to larger roles; by 1825, he had top billing at London's Coburg Theatre as Oronoko in A Slave's Revenge, soon to be followed by the role of Gambia in The Slave, and the title role of Shakespeare's Othello. He also played major roles in plays such as The Castle Spectre and The Padlock. In search of new and suitable material, Aldridge also appeared occasionally as white European characters, for which he would be made up with greasepaint and wig. Examples of these are Captain Dirk Hatteraick and Bertram in Rev. R. C. Maturin's Bertram, the title role in Shakespeare's Richard III, and Shylock in The Merchant of Venice.

Touring, and later years

In 1828, Aldridge visited Coventry while he was largely touring the English provinces. After his acting impressed the people of the city, he was made the manager at Coventry Theatre Royal, owned by Sir Skears Rew, and thus became the first ever African American to manage a British theatre.[12]

During the months when Aldridge remained in Coventry, he made various speeches about the evils of slavery. And after he left Coventry, his speeches and the impression he made, inspired the people of Coventry to go to the county hall, and petition to the Parliament, to abolish slavery.[12]

In 1831 Aldridge successfully played in Dublin; at several locations in southern Ireland, where he created a sensation in the small towns; as well as in Bath, England and Edinburgh, Scotland. The actor Edmund Kean praised his Othello, and since he was an African-American actor from the African Theatre, The Times termed him the "African Roscius", after the famed actor of ancient Rome. Aldridge used this to his benefit and expanded African references in his biography that appeared in playbills,[6] also identifying his birthplace as "Africa" in his entry in the 1851 census.[13]

By at least 1833 he had added the anti-heroic role of Zanga in Edward Young's The Revenge to his repertoire.[14][15] The Revenge (1721) race-flips the plot of Othello by showing how Zanga, a captured Moorish prince who has become the servant and confidant of the noble Don Alonzo, vengefully tricks him into believing his wife is unfaithful. Alonzo finally kills himself and Zanga exults: "Let Europe and her pallid sons go weep; / Let Afric and her hundred thrones rejoice: / Oh, my dear countrymen, look down and see / How I bestride your prostrate conqueror!"[16] An illustrated review of this performance[17] at the Surrey Theatre[18] shows Aldridge triumphing over Alonzo, dressed in flowing Moorish robes, which, according to the critic, "reminds one of the portraits of Abd-el Kader". The same reviewer praised Aldridge's comic talents in the contrasting role of Mungo (in the Bickerstaffe farce The Padlock), describing them as a refreshing corrective, "...differing entirely from the Ethiopian absurdities we have been taught to look upon as correct portraitures; his total abandon is very amusing."[18]

In 1841, Aldridge toured towns across Lincolnshire, performing in Gainsborough,[19] Grantham,[20] Spilsby,[21] and Horncastle.[22] In 1842, Aldridge performed in Lincoln; local newspapers reported that his arrival in a travelling coach was a remarkable sight and caused a stir with inhabitants of the city.[23][24] Despite the eye-catching arrival, Aldridge's performances were not well attended.[25] In June 1844 he made appearances on stage in Exmouth (Devon, England).[26] In 1847, he performed in Boston.[27] Aldridge returned to Lincoln in 1849 to favourable reviews.[28] The Lincoln Standard reported on Aldridge's performance, “his talents are first rate, and his conduct gentlemanly, strongly evidencing that mankind all have an equal capacity, if they had but the opportunity of receiving instruction.”[29]

In 1852, Aldridge chose Brussels in Belgium as the starting point of its first tour in continental and central Europe. He toured with successes all over Europe. He had particular success in Prussia, where he was presented to the Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, and performed for William IV of Prussia; he also performed in Budapest. An 1858 tour took him to Serbia and to the Russian Empire, where he became acquainted with Count Fyodor Tolstoy, Mikhail Shchepkin and Ukrainian poet and artist Taras Shevchenko, who did his portrait in pastel.[30] He introduced and increased interest in Shakespeare in some areas of Central Europe, and in Poland in particular. As an African American in the age of slavery, he became for some an identifying symbol also for the oppressed of Poland, drawing surveillance by the Russian government.[31]

Now of an appropriate age, about this time, he played the title role of King Lear (in England) for the first time. He purchased some property in England,[32] toured Russia again (1862), and applied for British citizenship (1863). Shortly before his death he was apparently ready to return to America to perform. It was reported that Aldridge had negotiated a 100-show-tour throughout the post-Civil War United States.[4] In its obituary of Aldridge, The New York Times stated he had been booked to appear in the city's Academy of Music in September, but "Death has prevented the fulfilment of his intention".[33] His funeral in Łódź, where he died unexpectedly, was accompanied by an elaborate procession, with the Art Society carrying his medals and awards through the streets, and his large tomb in the city cemetery was covered in flowers.[31]

Marriage and family

Soon after going to England, on 27 November 1825, Aldridge married Margaret Gill, an Englishwoman, at St George's, Bloomsbury.[34] He recorded in his Memoir that she was "the natural daughter of a member of Parliament, and a man of high standing in the county of Berks", but her father was in reality a stocking-weaver from Northallerton, Yorkshire. Lindfors suggests that Aldridge "may have invented this fiction to give her an air of respectability in polite society", raising her social status to protect her from criticism for marrying a black man. Their marriage angered the pro-slavery lobby, which attempted to end Aldridge's career.[35] The couple was married for 40 years until her death in 1864.[36]

Aldridge's first son, Ira Daniel, was born in May 1847. The identity of his mother is unknown, but it could not have been Margaret Aldridge, who was 49 years old and had been in ill health for years.[37] She raised Ira Daniel as her own; they shared a loving relationship until her death. He emigrated to Australia in February 1867.[38][39]

Aldridge bought 5 Hamlet Road, in the prosperous suburbs of Upper Norwood, London, in 1861–2 shortly before becoming a naturalised British citizen in 1863. It was where his wife, Margaret, and later his second wife, Amanda, brought up his children. He named the house ‘Luranah Villa’ in memory of his mother. It now bears his English Heritage blue plaque.[32]

A year after Margaret's death, on April 20, 1865, Aldridge married his mistress, the self-styled Swedish countess Amanda von Brandt (1834-1915). They had four children: Irene Luranah,[40] Ira Frederick and Amanda Aldridge, who all went on to musical careers, the two girls as opera singers. Their daughter Rachael Frederica was born shortly after Aldridge's death and died in infancy. Brandt died in 1915 and is buried at Highgate Woods, London.

Aldridge spent most of his final years with his family in Russia and continental Europe, interspersed with occasional visits to England. He planned to return to the post-Civil-War United States. After completing a 70-city tour of France in 1867 and his French tour of Belgium (Ghent and Brussels), Aldridge died of a prolonged lung condition on 7 August 1867 while visiting Łódź, than part of the Russian Empire, in Poland.[41] He was buried in the city's Old Evangelical Cemetery; 23 years passed before a proper tombstone was erected. His grave is tended by the Society of Polish Artists of Film and Theatre. A commemorative plaque was unveiled in 2014 at 175 Piotrkowska Street, where Aldridge was said to have died. The plaque was created by sculptor Marian Konieczny.

A half-length portrait of 1826 by James Northcote shows Aldridge dressed for the role of Othello, but in a relatively undramatic portrait pose, is on display at the Manchester Art Gallery (in the Manchester section). Aldridge performed in the city many times.[42] A blue plaque unveiled in 2007 commemorates Aldridge at 5 Hamlet Road in Upper Norwood, London.[32] The plaque describes him as the "African Roscius".[32]

The case of Stothard v. Aldridge

In 1856 Aldridge was successfully sued by actor William Stothard,[43] who alleged Aldridge had had an affair with his wife Emma[44] three years before, resulting in the birth of a son.[45] (Under English law at the time the husband of an adulterous wife was entitled to sue her lover for compensation.) At a hearing on January 14 in London before Mr. Justice Erle the jury found for the plaintiff Stothard, but in view of mitigating circumstances awarded him only £2 in damages.[46]

Aldridge was away on tour in Ireland when the trial took place[46] but he was heading the bill at a London theatre by the following year,[47] indicating the scandal caused his career no lasting damage.

Ira Aldridge Troupe

Aldridge enjoyed enormous fame as a tragic actor during his lifetime, but after his death, he was soon forgotten (in Europe). The news of Ira Aldridge's death in Poland and the record of his achievement as an actor reached the American black community slowly.[48] In African-American circles, Aldridge was a legendary figure. Many black actors viewed him as an inspirational model, so when his death was revealed, several amateur groups sought to honor his memory by adopting his name for their companies.[5]

Many troupes were being founded in various places around America. In the late nineteenth century Aldridge-titled troupes were established in Washington, DC, in Philadelphia, and in New Haven, their respective productions at the time being an adaptation of Kotzebue's Die Spanier in Peru by Sheridan as Pizarro in 1883, School by Thomas William Robertson in 1885, and George Melville Baker's Comrades in 1889.[5]

The most prominent troupe named for him was the Ira Aldridge Troupe in Philadelphia, founded in 1863, some 35 years after Aldridge left the US for good.[49] The Ira Aldridge Troupe was a minstrelsy group that caricatured Irish men. The Ira Aldridge Troupe is unique in annals of minstrelsy; it was named for a Black actor who had left his homeland some 35 years before and achieved fame in Europe. Unlike most, later, Black minstrel companies, the Aldridge Troupe apparently did not do plantation material, although they were billed as a 'contraband troupe'—that is, fugitive slaves. Perhaps because of their substantially Black audience, the troupe felt no need to "put on the mask." Although much of the material the group performed was standard fare, several of the company's acts were downright subversive.[49]

The Ira Aldridge Troupe appearing during the American Civil War made it "unique in the annals of minstrelsy." The Clipper (New York City) thought it was important enough to review; and it performed before a mixed audience, at a time when often white and black audiences were separated. Third, it was a black troupe presenting a program designed to appeal to their black audience. The Ira Aldridge Troupe performances eschewed the southern genre of old "darkies" longing for the plantation. The exclusion of southern nostalgia may have been in deference to a majority-black audience. The New York Clipper reported them as "A more incorrigible set of cusses we never saw; they beat our Bowery gods all to pieces."[5]

The troupe also created performances and songs that referred to the continuing Civil War. A ballad, "When the Cruel War is Over", became well known; it was performed by three members of the troupe—Miss S. Burton, Miss R. Clark, and Mr. C. Nixon. The song sold over a million copies of sheet music and was one of the most popular sentimental songs of the Civil War.[49] The song describes a soldier's farewell to his lady, the wounds he receives in battle, and his dying request for a last caress. The song, highly popular with white minstrel groups, was an example of the change in white minstrelsy that had been occurring at this time.[49]

Another popular production was a farce called The Irishman and the Stranger, with a Mr. Brown playing a character called Pat O'Callahan and a Mr. Jones playing the Stranger. This farce displayed black actors in white face speaking in a "nigger accent". The Clipper reporter referred to the performance as a "truly laughable affair, the 'Irish nagur' mixing up a rich Irish brogue promiscuously with the sweet nigger accent".[49] Perhaps the Aldridge Troupe's audience got its biggest satisfaction, however, from the role reversal inherent in the piece: since the beginning of minstrelsy, minstrels of Irish heritage, such as Dan Bryant and Richard Hooley, had been caricaturing Black men—now it was the turn of Black men to caricature the Irish.[49]

The history of minstrelsy also shows the cross-cultural influences, with Whites adopting elements of Black culture. The Ira Aldridge Troupe tried to pirate that piracy, and, in collaboration with its audience, turn minstrelsy to its own ends.[49]

Aldridge family

- Ira Daniel Aldridge, 1847–?. Teacher; convicted forger. Migrated to Australia in 1867.[50]

- Irene Luranah Pauline Aldridge, 1860–1932. Opera singer.[4]

- Ira Frederick Olaff Aldridge, 1862–1886. Musician and composer.[51]

- Amanda Christina Elizabeth Aldridge (Amanda Ira Aldridge), 1866–1956. Opera singer, teacher and composer under name of Montague Ring.[52]

- Rachael Margaret Frederika Aldridge, b.1868;[53] died in infancy 1869.[54]

Legacy and honors

- Aldridge received awards for his art from European heads of state and governments: the Prussian Gold Medal for Arts and Sciences from King Frederick William III, the Golden Cross of Leopold from the Czar of Russia, and the Maltese Cross from Bern, Switzerland.[55]

- During his successful tours, Aldridge had the distinguished honor of appearing before: Leopold I, King of Belgium; Frederick William IV, King of Prussia; the Prince and Princess of Prussia; Prince Frederick Wilhelm and Court; Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria; Sophia Archduchess of Austria; Ferdinand, Ex-Emperor of Austria; Archduke Albrecht, Viceroy of Hungary; Frederick Augustus and Maria of Saxony; the King and Queen of Holland; the Queen of Sweden; The Prince Regent of Baden; the Duke and Duchess of Saxe Cobourg; the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg Schwerin; the Reigning Duke of Brunswick; the Margrave and Margravine of Baden; and General Jellachich, Ban of Croatia, amongst others.

- Aldridge is the only African American to have a bronze plaque among the 33 actors honored at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon.

- A bust of Ira Aldridge by Pietro Calvi sits in the Grand Saloon of the Theatre Royal Drury Lane in London.

- Aldridge's legacy inspired the dramatic writing of African-American playwright Henry Francis Downing,[56] who in the early 20th century became "probably the first person of African descent to have a play of his or her own written and published in Britain."[57]

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Ira Aldridge in his 100 Greatest African Americans.

- His life was the subject of a play, Red Velvet, by Lolita Chakrabarti and starring Adrian Lester, produced at the Tricycle Theatre in London in 2012.

- Howard University Department of Theatre Arts, a historically black university in Washington, DC, has a theatre named after Ira Aldridge.

- Aldridge's Othello has been highly influential in starting a series of respected performances by African Americans in Othello in the 1800s and early 1900s, which includes: John A. Arneaux, John Hewlett, and Paul Robeson.[58]

- A blue plaque in Aldridge's honor was erected at Coventry, England.[12] Professor Tony Howard, who teaches in the Department of English and Comparative Literary Studies at the University of Warwick,[59] was campaigning for the commemoration of Aldridge's time in Coventry, with the Belgrade Theatre. He had also said that, in Coventry, where there was formerly little interest in the abolition of slavery, Aldridge had "changed the climate of thinking".[12] On 3 August 2017, a blue plaque was unveiled to honour Aldridge for his time in Coventry, and to commemorate the location of the theatre. The plaque was unveiled in the Upper Precinct in Coventry city centre, by Lord Mayor Councillor Tony Skipper[12] and was helped by actor Earl Cameron, whose voice coach was Aldridge's daughter, Amanda Ira Aldridge.

- A blue plaque was erected in 2007 by English Heritage at 5 Hamlet Road, Upper Norwood, London SE19 2AP, London Borough of Bromley.[32]

The Black Doctor (1847)

The Black Doctor, originally written in French by Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois, was adapted by Aldridge for the English stage. The Black Doctor is a romantic play about Fabian, a bi-racial physician, and his patient Pauline, the daughter of a French aristocrat. The couple falls in love and marries in secret. Although the play depicts racial and family conflict, and ends with Fabian's death, Aldridge was said to portray his title character with dignity.[60]

See also

References

- ^ Evans, Nicholas M (September 2002). "Ira aldridge: Shakespeare and minstrelsy". American Transcendental Quarterly. 16 (3): 165–187. ProQuest 222437800 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. p657

- ^ a b c Nelson, E.S. (2004). In African American Dramatists: An A-to-Z Guide. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood.

- ^ a b c d e f Ross, Alex (July 29, 2013). ""Othello's Daughter"". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hill, Errol G., and James Vernon Hatch. (2003). A History of African American Theatre. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d Lindfors, Bernth (2007). Ira Aldridge in Europe: How Aldridge controlled his identity as the 'African Roscius' (Audio documentary). Shakespeare in American Life. Folger Shakespeare Library. Archived transcript. Archived from the original (MP3) on December 18, 2015. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ "The Coburg Theatre (review)". The Times. London. October 11, 1825.

- ^ White, Shane (2007). James Hewlett after the African Grove: Shutting down the African Grove Theater (Audio documentary). Shakespeare in American Life. Folger Shakespeare Library. Archived transcript. Archived from the original (MP3) on December 18, 2015. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ "In the mid 19th century, the African-American actor Ira Aldridge and the English playwright C.A. Somerset collaborated on a new version that transformed Aaron, a Moor and the lover of the barbarian queen Tamora, from villain to hero, subverting racial stereotype. Aldridge and Somerset cut out most of the carnage and interpolated at least one scene from a contemporary melodrama that Aldridge had also starred in. Aldridge’s opinion: “I will venture to say that there is not a play on the stage with a more powerful climax.” A Scottish critic praised Aldridge’s performance as Aaron as “remarkable for energy, tempered by dignity and discretion.” Soloski, Alexis (April 4, 2019). "Let It Bleed: The Perverse Influence of 'Titus Andronicus'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ The Times (London, England), 11 October 1825, p. 2.

- ^ Herbert Marshall, Ira Aldridge: The African Tragedian,

- ^ a b c d e "First black Shakespearean actor honoured". BBC. August 3, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ 1851 England, Wales and Scotland census, folio 446, p. 30. Aldridge is staying at a boarding house in Derby with his wife and son, and gives his occupation as "Tragedian'".

- ^ Schomburg, Arthur Alfonso. "List showing the theatres and plays in various European cities where Ira Aldridge, the African Roscius, acted during the years 1827–1867". Harvard Library. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ "A collection of playbills from Theatre Royal, Dublin 1830-1839 Collection Item". British Library. Theatre Royal, Dublin. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ The Revenge: A Tragedy by Edward Young.

- ^ "The Theatre", Black Presence, The National Archives.

- ^ a b The Illustrated London News, 1 April 1848, p. 218.

- ^ "Lincolnshire Chronicle". March 26, 1841.

- ^ "Lincolnshire Chronicle". April 28, 1841.

- ^ "Stamford Mercury". April 30, 1841.

- ^ "Lincolnshire Chronicle". May 14, 1841.

- ^ The Lincoln Standard & General Advertiser. February 9, 1842.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Lincolnshire Chronicle". February 18, 1842.

- ^ "Stamford Mercury". February 25, 1842.

- ^ "Exmouth. This pleasant watering place has during the last two days been enlivened by the performances of the 'African Roscius'. Numerous assemblies have on each night testified their approbation of his impersonation of Othello and Revenge." in Trewman's Exeter Flying Post, 26 June 1844 (issue no. 4103).

- ^ "Lincolnshire Chronicle". December 10, 1847.

- ^ "Lincolnshire Times". January 30, 1849.

- ^ "The Lincoln Standard & General Advertiser". February 9, 1842.

- ^ "The Never Ending Tour – Ira Aldridge". journeys.dartmouth.edu. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Sakowska, Aleksandra (September 20, 2016). "Ira Aldridge's Polish Journey: Developing the Shakespearean Canon and Influencing Local Politics". European Studies Blog. British Library.

- ^ a b c d e "Blue plaque: Aldridge, Ira (1807–1867)". English Heritage. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ The New York Times, 12 August 1867: "Obituary: Ira Aldridge, the African Tragedian".

- ^ Lindfors, Bernth (1994). ""Nothing Extenuate, Nor Set Down Aught in Malice": New Biographical Information on Ira Aldridge". African American Review. 28 (3): 457–472. doi:10.2307/3041981. ISSN 1062-4783. JSTOR 3041981 – via JSTOR.

A page from a London marriage register (Fig. 1) shows that they were married on 27 November 1825 by Rev. L. H. Wynn in the presence of two witnesses, William Tanfield and Margaret Robinson. The ceremony took place at St. George's Church, Bloomsbury, a large church consecrated in 1730 that is still in use today.

- ^ "Black British Entertainers -Ira Aldridge". Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Lindfors, Bernth (2011). Ira Aldridge: The early years 1807-1833. University Rochester Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-58046-381-2. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ Lindfors, Bernth (1994). ""Nothing Extenuate, Nor Set Down Aught in Malice": New Biographical Information on Ira Aldridge". African American Review. 28 (3): 457–472. doi:10.2307/3041981. ISSN 1062-4783. JSTOR 3041981.

- ^ Lindfors, Bernth (2012),"The Lost Life of Ira Daniel Aldridge (Part 1)", Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture, No.2, (2012), pp.195-208. doi:10.2478/v10231-012-0064-5

- ^ Lindfors, Bernth (2013),"The Lost Life of Ira Daniel Aldridge (Part 2)", Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture, No.3, (2013), pp.235-251. doi:10.2478/texmat-2013-0037

- ^ "Shakespeare, Wagner, Aldridge". Alex Ross: The Rest Is Noise. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887, pp. 733–739.

- ^ Manchester Art Gallery

- ^ Lindfors, Bernth (2012). "The Lost Life of Ira Daniel Aldridge (Part 1)" (PDF). Text Matters. 2 (2): 197–198. doi:10.2478/v10231-012-0064-5. hdl:1885/59028. S2CID 199664361.

- ^ Emma Iggulden m. William Stothard 15 August 1850: see England and Wales Marriages (1850), vol. 1, p. 344, line 5

- ^ Darby, Nell (2017). Life on the Victorian Stage: Theatrical Gossip. PEN & SWORD HISTORY. p. 95. ISBN 9781473882430.

- ^ a b ’’The Times’’(London), 15 January 1856, p.9: Law Report

- ^ "City of London Theatre - Great Triumph of the African tragedian, Mr Ira Aldridge, who will this evening perform Shylock..." ’’The Times’’(London), 14 October 1857, p.9

- ^ Lindfors, Bernth. Ira Aldridge, the African Roscius. Rochester, New York: University of Rochester Press, 2007

- ^ a b c d e f g Shalom, Jack. "The Ira Aldridge Troupe: Early Black Minstrelsy in Philadelphia." African-American Review 28.4 (1994): 653–658

- ^ Lindfors, 2012; and 2013.

- ^ "Prof. Arthur LaBrew, Musicologist | Ellis Washington Report - Part 3". December 28, 2012.

- ^ The Times(London), 10 March 1956, p.9, 'Miss Amanda Ira Aldridge':"Miss Amanda Ira Aldridge, who was the last remaining pupil of the Swedish nightingale, Jenny Lind, died yesterday afternoon in hospital in Surrey, the day before her ninetieth birthday. She was one of the foundation members of the Royal College of Music and taught singing for 65 years. Her most famous pupils were the contralto Marion Anderson and bass baritone Paul Robeson. Using the pen name of Montagu Ring(sic), she composed several works, her most popular work being three African dances. Her last public appearance was on television on April 16, 1954, in Eric Robinson's "Music for You." She was the daughter of the Negro tragedian Ira Aldridge."

- ^ England and Wales Births 1868 (1st quarter): Croydon, Surrey, Vol. 2A, p.201, line no.215.

- ^ England and Wales Deaths 1869 (4th quarter): Croydon, Surrey, Vol. 2A,p.126, Line no.123.

- ^ Douglas O. Barnett, "Ira Aldridge", Black Past, accessed 15 October 2010.

- ^ Roberts, Brian (2012). "A London Legacy of Ira Aldridge: Henry Francis Downing and the Paratheatrical Poetics of Plot and Cast(e)". Modern Drama. 55 (3): 386–406. doi:10.3138/md.55.3.386. S2CID 162466396.

- ^ Chambers, Colin (2011). Black and Asian Theatre in Britain: A History. London: Routledge. p. 63.

- ^ Newmark, Paige. Othello: New Critical Essays. Edited by Philip C. Kolin. London and New York: Routledge, 2002.

- ^ Howard, Anthony (October 16, 2020). "Professor Tony Howard - University of Warwick". Warwick. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Hatch, James V., and Ted Shine, eds. Black Theatre U.S.A.. The Free Press, 1996 [1974], p. 4.

Further reading

- Aldridge, Ira Frederick. "The Black Doctor". Black Drama Database.

- Bourne, Stephen (2021). Deep Are the Roots: Trailblazers Who Changed Black British Theatre. Cheltenham: The History Press. ISBN 9780750999106. OCLC 1272990127.

- Hatch, James V.; Shine, Ted, eds. (1996). Black Theatre USA: Plays by African Americans. New York: Free Press. ISBN 9780684823089. OCLC 33131603.

- Kimmelman, Elaine (1982). Dark Comet. Avon Books. ISBN 9780380818280. OCLC 9948356.

- Kujawińska-Courtney, Krystyna (2009). Ira Aldridge (1807–1867): Dzieje pierwszego czarnoskorego tragika szekspirowskiego (in Polish). Kraków: Universitas. ISBN 9788324208289.

- Kujawińska-Courtney, Krystyna; Łukowska, Maria Antonina, eds. (2009). Ira Aldridge 1807–1867. The Great Shakespearean Tragedian on the Bicentennial Anniversary of His Birth. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631577349. OCLC 435633062.

- Lindfors, Bernth. "Aldridge in Europe". Shakespeare in American Life. Archived from the original on December 18, 2015. – Folger Shakespeare Library's public radio documentary

- Rzepka, Charles. "Introduction: Obi, Aldridge and Abolition". Praxis Series. Romantic Circles. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023.

- Shyllon, Folarin Olawale (1977). Black people in Britain, 1555–1833. London: Oxford University Press for the Institute of Race Relations. ISBN 9780192184139. OCLC 4212069.

- Herbert Marshall, Further Research on Ira Aldridge, the Negro Tragedian, FRSA, Center for Soviet & East European Studies, Southern Illinois University.

- Herbert Marshall Collection of Ira Aldridge, Collection 139 Archived November 27, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Southern Illinois University Special Research Collection: Theatre, material which Marshall collected for his biography of Aldridge.

External links

- "Aldridge Collection" finding aid for Northwestern University Special Collections' Aldridge family archival collection

- George F. Bragg, "Biography of Ira Aldridge", Men of Maryland

- Memoir and Theatrical Career of Ira Aldridge, the African Roscius, 1850 biography of Aldridge, quoting contemporary reviews of his performances

- 1807 births

- 1867 deaths

- 19th-century American male actors

- 19th-century British male actors

- 19th-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 19th-century British dramatists and playwrights

- African Free School alumni

- African-American dramatists and playwrights

- African-American male actors

- American emigrants to the United Kingdom

- American male Shakespearean actors

- American male stage actors

- British male stage actors

- Male actors from New York City