Chaos theory

In mathematics and physics, chaos theory describes the behavior of certain nonlinear dynamical systems that may exhibit dynamics that are highly sensitive to initial conditions (popularly referred to as the butterfly effect). As a result of this sensitivity, which manifests itself as an exponential growth of perturbations in the initial conditions, the behavior of chaotic systems appears to be random. This happens even though these systems are deterministic, meaning that their future dynamics are fully defined by their initial conditions, with no random elements involved. This behavior is known as deterministic chaos, or simply chaos.

Overview

Chaotic behavior has been observed in the laboratory in a variety of systems including electrical circuits, lasers, oscillating chemical reactions, fluid dynamics, and mechanical and magneto-mechanical devices. Observations of chaotic behaviour in nature include the dynamics of satellites in the solar system, the time evolution of the magnetic field of celestial bodies, population growth in ecology, the dynamics of the action potentials in neurons, and molecular vibrations. Everyday examples of chaotic systems include weather and climate.[1] There is some controversy over the existence of chaotic dynamics in the plate tectonics and in economics.[2] [3] [4]

Systems that exhibit mathematical chaos are deterministic and thus orderly in some sense; this technical use of the word chaos is at odds with common parlance, which suggests complete disorder. A related field of physics called quantum chaos theory studies systems that follow the laws of quantum mechanics. Recently, another field, called relativistic chaos,[5] has emerged to describe systems that follow the laws of general relativity.

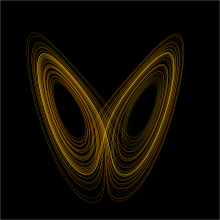

As well as being orderly in the sense of being deterministic, chaotic systems usually have well defined statistics. For example, the Lorenz system pictured is chaotic, but has a clearly defined structure. Bounded chaos is a useful term for describing models of disorder.

History

The first discoverer of chaos can plausibly be argued to be Jacques Hadamard, who in 1898 published an influential study of the chaotic motion of a free particle gliding frictionlessly on a surface of constant negative curvature. In the system studied, Hadamard's billiards, Hadamard was able to show that all trajectories are unstable, in that all particle trajectories diverge exponentially from one another, with a positive Lyapunov exponent.

In the early 1900s Henri Poincaré, while studying the three-body problem, found that there can be orbits which are nonperiodic, and yet not forever increasing nor approaching a fixed point. Much of the early theory was developed almost entirely by mathematicians, under the name of ergodic theory. Later studies, also on the topic of nonlinear differential equations, were carried out by G.D. Birkhoff, A.N. Kolmogorov, M.L. Cartwright, J.E. Littlewood, and Stephen Smale. Except for Smale, these studies were all directly inspired by physics: the three-body problem in the case of Birkhoff, turbulence and astronomical problems in the case of Kolmogorov, and radio engineering in the case of Cartwright and Littlewood. Although chaotic planetary motion had not been observed, experimentalists had encountered turbulence in fluid motion and nonperiodic oscillation in radio circuits without the benefit of a theory to explain what they were seeing.

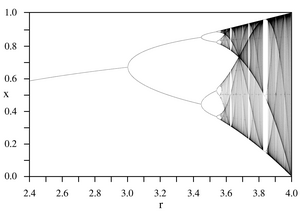

Chaos theory progressed more rapidly after mid-century, when it first became evident for some scientists that linear theory, the prevailing system theory at that time, simply could not explain the observed behaviour of certain experiments like that of the logistic map. The main catalyst for the development of chaos theory was the electronic computer. Much of the mathematics of chaos theory involves the repeated iteration of simple mathematical formulas, which would be impractical to do by hand. Electronic computers made these repeated calculations practical. One of the earliest electronic digital computers, ENIAC, was used to run simple weather forecasting models.

An early pioneer of the theory was Edward Lorenz whose interest in chaos came about accidentally through his work on weather prediction in 1961. Lorenz was using a basic computer, a Royal McBee LGP-30, to run his weather simulation. He wanted to see a sequence of data again and to save time he started the simulation in the middle of its course. He was able to do this by entering a printout of the data corresponding to conditions in the middle of his simulation which he had calculated last time.

To his surprise the weather that the machine began to predict was completely different from the weather calculated before. Lorenz tracked this down to the computer printout. The printout rounded variables off to a 3-digit number, but the computer worked with 6-digit numbers. This difference is tiny and the consensus at the time would have been that it should have had practically no effect. However Lorenz had discovered that small changes in initial conditions produced large changes in the long-term outcome.

Yoshisuke Ueda independently identified a chaotic phenomenon as such by using an analog computer on November 27, 1961. The chaos exhibited by an analog computer is a real phenomenon, in contrast with those that digital computers calculate, which has a different kind of limit on precision. Ueda's supervising professor, Hayashi, did not believe in chaos, and thus he prohibited Ueda from publishing his findings until 1970.

The term chaos as used in mathematics was coined by the applied mathematician James A. Yorke.

The availability of cheaper, more powerful computers broadens the applicability of chaos theory. Currently, chaos theory continues to be a very active area of research.

Chaotic dynamics

For a dynamical system to be classified as chaotic, it must have the following properties:[6]

- it must be sensitive to initial conditions,

- it must be topologically mixing, and

- its periodic orbits must be dense.

Sensitivity to initial conditions means that each point in such a system is arbitrarily closely approximated by other points with significantly different future trajectories. Thus, an arbitrarily small perturbation of the current trajectory may lead to significantly different future behaviour.

Sensitivity to initial conditions is popularly known as the "butterfly effect", so called because of the title of a paper given by Edward Lorenz in 1972 to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C. entitled Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly’s Wings in Brazil set off a Tornado in Texas? The flapping wing represents a small change in the initial condition of the system, which causes a chain of events leading to large-scale phenomena. Had the butterfly not flapped its wings, the trajectory of the system might have been vastly different.

Sensitivity to initial conditions is often confused with chaos in popular accounts. It can also be a subtle property, since it depends on a choice of metric, or the notion of distance in the phase space of the system. For example, consider the simple dynamical system produced by repeatedly doubling an initial value (defined by the mapping on the real line from x to 2x). This system has sensitive dependence on initial conditions everywhere, since any pair of nearby points will eventually become widely separated. However, it has extremely simple behaviour, as all points except 0 tend to infinity. If instead we use the bounded metric on the line obtained by adding the point at infinity and viewing the result as a circle, the system no longer is sensitive to initial conditions. For this reason, in defining chaos, attention is normally restricted to systems with bounded metrics, or closed, bounded invariant subsets of unbounded systems.

Even for bounded systems, sensitivity to initial conditions is not identical with chaos. For example, consider the two-dimensional torus described by a pair of angles (x,y), each ranging between zero and 2π. Define a mapping that takes any point (x,y) to (2x, y + a), where a is any number such that a/2π is irrational. Because of the doubling in the first coordinate, the mapping exhibits sensitive dependence on initial conditions. However, because of the irrational rotation in the second coordinate, there are no periodic orbits, and hence the mapping is not chaotic according to the definition above.

Topologically mixing means that the system will evolve over time so that any given region or open set of its phase space will eventually overlap with any other given region. Here, "mixing" is really meant to correspond to the standard intuition: the mixing of colored dyes or fluids is an example of a chaotic system.

Attractors

Some dynamical systems are chaotic everywhere (see e.g. Anosov diffeomorphisms) but in many cases chaotic behaviour is found only in a subset of phase space. The cases of most interest arise when the chaotic behaviour takes place on an attractor, since then a large set of initial conditions will lead to orbits that converge to this chaotic region.

An easy way to visualize a chaotic attractor is to start with a point in the basin of attraction of the attractor, and then simply plot its subsequent orbit. Because of the topological transitivity condition, this is likely to produce a picture of the entire final attractor.

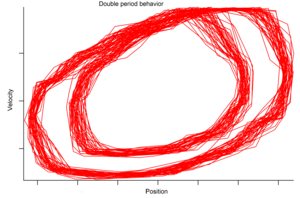

For instance, in a system describing a pendulum, the phase space might be two-dimensional, consisting of information about position and velocity. One might plot the position of a pendulum against its velocity. A pendulum at rest will be plotted as a point, and one in periodic motion will be plotted as a simple closed curve. When such a plot forms a closed curve, the curve is called an orbit. Our pendulum has an infinite number of such orbits, forming a pencil of nested ellipses about the origin.

Strange attractors

While most of the motion types mentioned above give rise to very simple attractors, such as points and circle-like curves called limit cycles, chaotic motion gives rise to what are known as strange attractors, attractors that can have great detail and complexity. For instance, a simple three-dimensional model of the Lorenz weather system gives rise to the famous Lorenz attractor. The Lorenz attractor is perhaps one of the best-known chaotic system diagrams, probably because not only was it one of the first, but it is one of the most complex and as such gives rise to a very interesting pattern which looks like the wings of a butterfly. Another such attractor is the Rössler map, which experiences period-two doubling route to chaos, like the logistic map.

Strange attractors occur in both continuous dynamical systems (such as the Lorenz system) and in some discrete systems (such as the Hénon map). Other discrete dynamical systems have a repelling structure called a Julia set which forms at the boundary between basins of attraction of fixed points - Julia sets can be thought of as strange repellers. Both strange attractors and Julia sets typically have a fractal structure.

The Poincaré-Bendixson theorem shows that a strange attractor can only arise in a continuous dynamical system if it has three or more dimensions. However, no such restriction applies to discrete systems, which can exhibit strange attractors in two or even one dimensional systems.

The initial conditions of three or more bodies interacting through gravitational attraction (see the n-body problem) can be arranged to produce chaotic motion.

Minimum complexity of a chaotic system

Simple systems can also produce chaos without relying on differential equations. An example is the logistic map, which is a difference equation (recurrence relation) that describes population growth over time.

Even the evolution of simple discrete systems, such as cellular automata, can heavily depend on initial conditions. Stephen Wolfram has investigated a cellular automaton with this property, termed by him rule 30.

A minimal model for conservative (reversible) chaotic behavior is provided by Arnold's cat map.

Mathematical theory

Sarkovskii's theorem is the basis of the Li and Yorke (1975) proof that any one-dimensional system which exhibits a regular cycle of period three will also display regular cycles of every other length as well as completely chaotic orbits.

Mathematicians have devised many additional ways to make quantitative statements about chaotic systems. These include: fractal dimension of the attractor, Lyapunov exponents, recurrence plots, Poincaré maps, bifurcation diagrams, and transfer operator.

Applications

Chaos theory is applied in many scientific disciplines: mathematics, biology, computer science, economics, engineering, finance, philosophy, physics, politics, population dynamics, psychology, and robotics.[7]

Chaos theory is also currently being applied to medical studies of epilepsy, specifically to the prediction of seemingly random seizures by observing initial conditions.[8]

Chaos theory in the media

Movies

- The 1993 movie Jurassic Park

- The 1998 movie π

- The 2004 movie The Butterfly Effect

- The 2006 movie The Science of Sleep

- The 2007 movie Chaos

Books

Theatre

- Tom Stoppard's "Arcadia" (a fictional account of early and contemporary studies; also thermodynamics and determinism)

See also

- Examples of chaotic systems

- Arnold's cat map

- Bouncing Ball Simulation System

- Chua's circuit

- Double pendulum

- Dynamical billiards

- Economic bubble

- Hénon map

- Horseshoe map

- Logistic map

- Lorenz attractor

- Rössler Map

- Standard map

- Swinging Atwood's Machine

- Other related topics

- Anosov diffeomorphism

- Bifurcation theory

- Chaos theory in organizational development

- Complexity

- Control of chaos

- Edge of chaos

- Fractal

- Predictability

- Santa Fe Institute

- Synchronization of chaos

- People

- Mitchell Feigenbaum

- Brosl Hasslacher

- Michel Hénon

- Edward Lorenz

- Aleksandr Lyapunov

- Benoît Mandelbrot

- Henri Poincaré

- Otto Rössler

- David Ruelle

- Oleksandr Mikolaiovich Sharkovsky

- Floris Takens

- James A. Yorke

References

- ^ Sneyers, R: "Climate Chaotic Instability: Statistical Determination and Theoretical Background", 8(5):517-532

- ^ Apostolos Serletis and Periklis Gogas,Purchasing Power Parity Nonlinearity and Chaos, in: Applied Financial Economics, 10, 615-622, 2000.

- ^ Apostolos Serletis and Periklis Gogas Template:PDFlink, in: The Energy Journal, 20, 83-103, 1999.

- ^ Apostolos Serletis and Periklis Gogas, Chaos in East European Black Market Exchange Rates, in: Research in Economics, 51, 359-385, 1997.

- ^ A. E. Motter, Relativistic chaos is coordinate invariant, in: Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 231101 (2003).

- ^ Hasselblatt, Boris (2003). A First Course in Dynamics: With a Panorama of Recent Developments. Cambridge University

Press. ISBN 0521587506.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); line feed character in|publisher=at position 21 (help) - ^ Metaculture.net, metalinks: Applied Chaos, 2007.

- ^ Comdig.org, Complexity Digest 199.06

Literature

Articles

- Li, T. Y. and Yorke, J. A. "Period Three Implies Chaos." American Mathematical Monthly 82, 985-992, 1975.

- Kolyada, S. F. "Li-Yorke sensitivity and other concepts of chaos", Ukrainian Math. J. 56 (2004), 1242--1257.

Textbooks

- Alligood, K. T. (1997). Chaos: an introduction to dynamical systems. Springer-Verlag New York, LLC. ISBN 0-387-94677-2.

- Baker, G. L. (1996). Chaos, Scattering and Statistical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39511-9.

- Badii, R.; Politi A. (1997). "Complexity: hierarchical structures and scaling in physics". Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521663857.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Devaney, Robert L. (2003). An Introduction to Chaotic Dynamical Systems, 2nd ed,. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-4085-3.

- Gollub, J. P.; Baker, G. L. (1996). Chaotic dynamics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47685-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gutzwiller, Martin (1990). Chaos in Classical and Quantum Mechanics. Springer-Verlag New York, LLC. ISBN 0-387-97173-4.

- Hoover, William Graham (1999,2001). Time Reversibility, Computer Simulation, and Chaos. World Scientific. ISBN 981-02-4073-2.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Kiel, L. Douglas; Elliott, Euel W. (1997). Chaos Theory in the Social Sciences. Perseus Publishing. ISBN 0-472-08472-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Moon, Francis (1990). Chaotic and Fractal Dynamics. Springer-Verlag New York, LLC. ISBN 0-471-54571-6.

- Ott, Edward (2002). Chaos in Dynamical Systems. Cambridge University Press New, York. ISBN 0-521-01084-5.

- Strogatz, Steven (2000). Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos. Perseus Publishing. ISBN 0-7382-0453-6.

- Sprott, Julien Clinton (2003). Chaos and Time-Series Analysis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850840-9.

- Tél, Tamás; Gruiz, Márton (2006). Chaotic dynamics: An introduction based on classical mechanics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83912-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tufillaro, Abbott, Reilly (1992). An experimental approach to nonlinear dynamics and chaos. Addison-Wesley New York. ISBN 0-201-55441-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Semitechnical and popular works

- Ralph H. Abraham and Yoshisuke Ueda (Ed.), The Chaos Avant-Garde: Memoirs of the Early Days of Chaos Theory, World Scientific Publishing Company, 2001, 232 pp.

- Michael Barnsley, Fractals Everywhere, Academic Press 1988, 394 pp.

- Richard J Bird, Chaos and Life: Complexity and Order in Evolution and Thought, Columbia University Press 2003, 352 pp.

- John Briggs and David Peat, Turbulent Mirror: : An Illustrated Guide to Chaos Theory and the Science of Wholeness, Harper Perennial 1990, 224 pp.

- John Briggs and David Peat, Seven Life Lessons of Chaos: Spiritual Wisdom from the Science of Change, Harper Perennial 2000, 224 pp.

- Lawrence A. Cunningham, From Random Walks to Chaotic Crashes: The Linear Genealogy of the Efficient Capital Market Hypothesis, George Washington Law Review, Vol. 62, 1994, 546 pp.

- Leon Glass and Michael C. Mackey, From Clocks to Chaos: The Rhythms of Life, Princeton University Press 1988, 272 pp.

- James Gleick, Chaos: Making a New Science, New York: Penguin, 1988. 368 pp.

- John Gribbin, Deep Simplicity,

- L Douglas Kiel, Euel W Elliott (ed.), Chaos Theory in the Social Sciences: Foundations and Applications, University of Michigan Press, 1997, 360 pp.

- Arvind Kumar, Chaos, Fractals and Self-Organisation ; New Perspectives on Complexity in Nature , National Book Trust, 2003.

- Hans Lauwerier, Fractals, Princeton University Press, 1991.

- Edward Lorenz, The Essence of Chaos, University of Washington Press, 1996.

- Heinz-Otto Peitgen and Dietmar Saupe (Eds.), The Science of Fractal Images, Springer 1988, 312 pp.

- Clifford A. Pickover, Computers, Pattern, Chaos, and Beauty: Graphics from an Unseen World , St Martins Pr 1991.

- Ilya Prigogine and Isabelle Stengers, Order Out of Chaos, Bantam 1984.

- H.-O. Peitgen and P.H. Richter, The Beauty of Fractals : Images of Complex Dynamical Systems, Springer 1986, 211 pp.

- David Ruelle, Chance and Chaos, Princeton University Press 1993.

- David Ruelle, Chaotic Evolution and Strange Attractors, Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Peter Smith, Explaining Chaos, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Ian Stewart, Does God Play Dice?: The Mathematics of Chaos , Blackwell Publishers, 1990.

- Steven Strogatz, Sync: The emerging science of spontaneous order, Hyperion, 2003.

- Yoshisuke Ueda, The Road To Chaos, Aerial Pr, 1993.

- M. Mitchell Waldrop, Complexity : The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos, Simon & Schuster, 1992.

External links

- Nonlinear Dynamics Research Group with Animations in Flash

- The Chaos group at the University of Maryland

- The Chaos Hypertextbook. An introductory primer on chaos and fractals.

- Society for Chaos Theory in Psychology & Life Sciences

- Interactive live chaotic pendulum experiment, allows users to interact and sample data from a real working damped driven chaotic pendulum

- Nonlinear dynamics: how science comprehends chaos, talk presented by Sunny Auyang, 1998.

- Nonlinear Dynamics. Models of bifurcation and chaos by Elmer G. Wiens

- Gleick's Chaos (excerpt)

- Systems Analysis, Modelling and Prediction Group at the University of Oxford.