Afro-Puerto Ricans

| Black history in Puerto Rico | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| style="text-align:center;" Template:Bg-gold colspan=5|Notable Puerto Ricans of African Ancestry | |||||||

|

1. 1.Arturo Alfonso Schomburg 2.José Celso Barbosa 3.Rafael Hernández Marín | |||||||

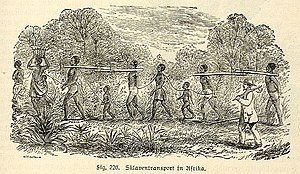

Black history in Puerto Rico initially began with the African freeman who arrived with the Spanish Conquistadors. The Spaniards enslaved the Tainos who were the native inhabitants of the island and many of them died as a result of the cruel treatment that they had received. This presented a problem for the Spanish Crown since they depended on slavery as a means of manpower to work the mines and build forts. Their solution was to import slaves from Africa and as a consequence the vast majority of the Africans who immigrated to Puerto Rico did so as a result of the slave trade. The Africans in Puerto Rico came from various points of Africa, and suffered many hardships and were subject to cruel treatment.

When the gold mines were declared depleted and no longer produced the precious metal, the Spanish Crown ignored Puerto Rico and the island became mainly a garrison for the ships. Africans from British and French possessions in the Caribbean were encouraged to immigrate to Puerto Rico and as freemen provided a population base to support the Puerto Rican garrison and its forts.

The Spanish decree of 1789 allowed the slaves to earn or buy their freedom. However, this did little to help them in their situation and eventually many slaves rebelled, most notably in the revolt against Spanish rule known as the "Grito de Lares. On March 22, 1873, slavery was abolished in Puerto Rico.

The Africans that came to Puerto Rico overcame many obstacles and particularly after the Spanish-American War, their descendents helped shape the political institutions of the island. Their contributions to the music, art, language, and heritage became the foundation of Puerto Rican culture.

First Africans in Puerto Rico

According to historians, the first free black man arrived in the island in 1509. Juan Garrido, a conquistador who belonged to Juan Ponce de León's entourage was the first black man to set foot on the island and in the New World. Another free black man who accompanied de León was Pedro Mejías. It is believed that Mejías married a Taíno woman chief (a cacica) by the name of Luisa.[1]

When Ponce de León and the Spaniards arrived in the island of "Borinken" (Puerto Rico), they were greeted by the Cacique Agüeybaná, the supreme leader of the peaceful Taíno tribes in the island. Agüeybaná helped to maintain the peace between the Taínos and the Spaniards. However, the peace would be short-lived because the Spaniards soon took advantage of the Taínos' good faith and enslaved them, forcing them to work in the gold mines and in the construction of forts. Many Taínos died as a result of either the cruel treatment that they had received or of the smallpox disease epidemic which had attacked the island. Many Taínos either committed suicide or left the island after the failed Taíno revolt of 1511.[2]

Friar Bartolomé de las Casas, who had accompanied Ponce de León to the New World, was outraged by the treatment of the Spaniards against the Taínos and protested in 1512 in front of the council of Burgos of the Spanish Courts. He fought for the freedom of the natives and was able to secure their rights. The Spanish colonists, who feared losing their labor force, protested before the courts. The colonists in Puerto Rico complained that they not only needed the manpower to work the mines and on the fortifications, but also in the thriving sugar industry. As an alternative Las Casas suggested the importation and use of black slaves. In 1517, the Spanish Crown permitted its subjects to import twelve slaves each in what became the beginning of the slave trade in the New World.[3]

According to historian Luis M. Diaz, the largest contingent of Africans came from the Gold Coast, Nigeria, and Dahomey, or the region known as the area of Guineas, the Slave Coast. However, the vast majority came from the Yorubas and Igbo tribe from Nigeria and the Bantus from the Guineas. The number of slaves in Puerto Rico rose from 1,500 in 1530 to 15,000 by 1555. The slaves were branded on the forehead with a stamp so people would know they were brought in legally and it prevented them from being kidnapped. The method of hot branding was no longer used after 1784.[4]

African slaves were sent to work the gold mines, as a replacement of the lost Taino manpower, or to work in the fields in the island's ginger and sugar industry. They were allowed to live with family in a bohio (hut) on the master's land and was given a patch of land where they could plant and grow vegetables and fruits. Blacks had little or no opportunity for advancement and faced discrimination from Spaniards. The slave was educated by his or her master and soon learned to speak his language. They enriched the "Puerto Rican Spanish" language by adding some words of their own and educated their children with what they had learned from their masters. The Spaniards considered the blacks superior to the Taínos, since the Taínos were unwilling to assimilate their ways. The slave had no choice but to convert to Christianity, they were baptized by the Catholic Church and assumed the surnames of their masters. It should be noted that many slaves were subject to harsh treatment which in cases included rape. The majority of the Conquistadors and farmers who settled the island had arrived without women and most of them intermarried with blacks or Taínos creating a mixture of races that was to become known as the "mestizo's" or "mulattos". This mixture was to become the basis of the Puerto Rican people.[4]

By 1570, the gold mines were declared depleted and no longer produced the precious metal. After gold mining came to an end in the island, the Spanish Crown basically ignored Puerto Rico by changing the routes of the west to the north. The island became mainly a garrison for the ships that would pass on their way to or from the other and richer colonies. An official Spanish edict of 1664 offered freedom and land to African people from non-Spanish colonies, such as Jamaica and St. Dominique (Haiti), who immigrated to Puerto Rico and provided a population base to support the Puerto Rican garrison and its forts. These freeman who settled the western and southern parts of the island, soon adopted the ways and customs of the Spaniards. Some joined the local militia which fought against the British in their many attempts to invade the island. It should be noted that the escaped slaves and freedman who immigrated from the West Indies, kept their former masters surnames which normally was either English or French. This is why it is not uncommon for Puerto Ricans of African ancestry to have non-Spanish surnames.[4]

Royal Decree of Graces of 1789

By the 17th Century slaves were permitted to obtain their freedom under the following circumstances:

- A slave could be freed in a church or outside of it, before a judge, by testament or letter in the presence of his master.

- A slave could be freed against his master’s will by denouncing a forced rape, by denouncing a counterfeiter, by discovering disloyalty against the king, and by denouncing murder against his master.

- Any slave who received part of his master's estate in his master’s will automatically became free.

- If a slave were left as guardian to his master’s children he also became free.

- If slave parents in Hispanic America had ten children, the whole family went free.[5]

In 1789, the Spanish Crown issued the "Royal Decree of Graces of 1789", which set new rules in regard to the commercialization of slaves and added restrictions to the granting of freeman status. The decree granted its subjects the right to purchase slaves and to participate in the flourishing business of slave trading in the Caribbean. Later that year a new slave code, also known as "El Código Negro" (The Black code), was introduced.[6]

The slave could buy his freedom if his master was willing to sell and by paying the price sought. Slaves were allowed to earn money during their spare time by working as shoemakers, cleaning clothes, or by selling the produce which they were allowed to grow in the small patch of land given to them by their masters. Another means by which they were allowed to pay for their freedom was by installments. They were allowed to make payments in installments for a new born child, not yet baptized, which cost half the going price for a baptized child. In Puerto Rico there was no racial stigma of racial inferiority since slavery, on an individual basis, could be eliminated by a fixed purchasing price.[6] Many of these freeman started settlements in the areas which became known as Cangrejos (Santurce), Carolina, Canóvanas, Loíza, Loíza Aldea, and Luquillo. Some even became slave owners themselves.[4]

19th Century

Famous Puerto Rican Freeman

One of the most renowned Puerto Ricans of African ancestry was Rafael Cordero (1790 – 1868), a freeman born in San Juan, Puerto Rico. He became known as "The Father of Public Education in Puerto Rico". Cordero was a self-educated Puerto Rican who provided free schooling to children regardless of their race. Among the distinguished alumni who attended Cordero's school were future abolitionists Román Baldorioty de Castro, Alejandro Tapia y Rivera, and José Julián Acosta. Cordero proved that racial and economic integration could be possible and accepted. In 2004, the Roman Catholic Church, upon the request of San Juan Archbishop Roberto González Nieves, began the process of Cordero's beatification.[7]

José Campeche (1751 — 1809), was another Puerto Rican of African ancestry who contributed greatly to the island's culture. Campeche's father Tomás Campeche, was a freed slave born in Puerto Rico, and María Jordán Marqués, his mother, came from the Canary Islands. Because of this mixed descent, he was identified as a mulatto, a common term during his time. Campeche is the first known Puerto Rican artist and is considered by many as one of its best. He distinguished himself with his paintings related to religious themes and of governors and other important personalities.[8]

Capt. Miguel Henriquez (c.1680 — 17??), a former pirate who became Puerto Rico's first black military hero when he organized an expeditionary force which fought and defeated the British in the island of Vieques. Capt. Henriques was received as a national hero when he returned the island of Vieques back to the Spanish Empire and to the governorship of Puerto Rico. He was awarded "La Medalla de Oro de la Real Efigie" and the Spanish Crown named him "Captain of the Seas" awarding him a letter of marque and reprisal which granted him the privileges of a privateer.[9]

The Royal Decree of Graces of 1815

The Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 was a legal order approved by the Spanish Crown in the early half of the 19th Century to encourage Spaniards and later Europeans of non-Spanish origin to settle and populate the colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico. The decree encouraged slave labor to revive agriculture and attract new settlers. The new agricultural class now immigrating from other countries of Europe sought slave labor in large numbers and cruelty became the order of the day. It is for this reason that a series of slave uprisings occurred on the island, from the early 1820s until 1868 in what is known as the Grito de Lares.[10] The 1834 Royal census of Puerto Rico established that 11% of the population were slaves, 35% were colored freemen and 54% were white.[11]

| Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1827 | ||||

| 1834 | ||||

| 1847 |

Rose Clemente, a black Puerto Rican columnist wrote "Until 1846, Blacks on the island had to carry a notebook (Libreta system) to move around the island, like the passbook system in apartheid South Africa."[12]

Abolitionists

By the mid 19th century, a committee of abolitionists was formed in Puerto Rico which included many prominent Puerto Ricans.

Dr. Ramón Emeterio Betances (1827 — 1898), whose parents were wealthy landowners, believed in the abolition of slavery and together with fellow Puerto Rican and abolitionist Segundo Ruiz Belvis (1829 — 1867) founded a clandestine organization called "The Secret Abolitionist Society". The objective of the society was to free children who were slaves, by the sacrament of Baptism. The event, which was also known as "aguas de libertad" (waters of liberty), was carried out at the Catheral of Mayagüez. When the child was baptized, Betances would give money to the parents which they in turn used to buy the child's freedom from his master.[13]

José Julián Acosta (1827 — 1891) was a member of a Puerto Rican commission, which included Ramón Emeterio Betances, Segundo Ruiz Belvis, and Francisco Mariano Quiñones (1830 — 1908). The commission participated in the "Overseas Information Committee" which met in Madrid, Spain. There, Acosta presented the argument for the abolition of slavery in Puerto Rico.[14]

On November 19, 1872, Román Baldorioty de Castro (1822 — 1889) together with Luis Padial (1832 — 1879), Julio Vizcarrondo (1830 — 1889) and the Spanish Minister of Overseas Affairs, Segismundo Moret (1833 — 1913), presented a proposal for the abolition of slavery. On March 22, 1873, the Spanish government approved the proposal which became known as the Moret Law.[15] This edict granted freedom to slaves over 60 years of age, those belonging to the state, and children born to slaves after September 17, 1868. Most importantly for genealogy purposes, the Moret Law established the Central Slave Registrar which in 1872 began gathering the following data on the island's slave population: name, country of origin, present residence, names of parents, sex, marital status, trade, age, physical description, and master's name.[16]

The Spanish government had lost most of its possessions in the New World by 1850. After the successful slave rebellion against the French in St Dominique (Haiti) in 1803, the Spanish Crown became fearful that the "Criollos" (native born) of Puerto Rico and Cuba, her last two remaining possessions, may follow suit. Therefore, the Spanish government issued the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815, attracting European immigrants from non-Spanish countries to populate the island believing that these new immigrants would be more loyal to Spain. However, they did not expect the new immigrants to racially intermarry as they did and identify themselves completely with their new homeland.[17]

On May 31, 1848, the Governor of Puerto Rico Juan Prim, in fear of an independence or slavery revolt imposed draconian laws, "El Bando contra La Raza Africana", to control the behavior of all Black Puerto Ricans, slave or free.[18] On September 23, 1868, slaves, who were promised their freedom, participated in the short failed revolt against Spain which became known in the history books as "El Grito de Lares" or "The Cry of Lares". Many of the participants were imprisoned or executed.[19]

Abolition of Slavery

On March 22, 1873, slavery was abolished in Puerto Rico. Slave owners were to free their slaves in exchange of a monetary compensation. The majority of the freed slaves continued to work for their former masters with the difference that they were now freeman and received what was considered a just pay for their labor.[20]

The freed slaves were able to fully integrate themselves into Puerto Rico's society. It cannot be denied that racism has existed in Puerto Rico since racism is something that exists in every country, however, racism in Puerto Rico did not exist to the extent of other places in the New World, possibly because of the following factors:

- In the 8th century, nearly all of Spain was conquered (711 — 718), by the Muslim Moors who had crossed over from North Africa. The first blacks were brought to Spain during Arab domination by North African merchants. By the middle of the 13th century all of the Iberian peninsula had been reconquered. A section of the city of Seville, which once was a Moorish stronghold, was inhabited by thousands of blacks. Blacks became freeman after converting to Christianity and lived fully integrated in Spanish society. Black women were highly sought after by Spanish males. Spain's exposure to people of color over the centuries accounted for the positive racial attitudes that were to prevail in the New World. Therefore, it was no surprise that the first conquistadors who arrived to the island, intermarried with the native Taínos and later with the African immigrants.[4]

- The Catholic Church played an instrumental role in the human dignity and social integration of the black man in Puerto Rico. The church insisted that every slave be baptized and converted to the Catholic faith. In accordance to the church's doctrine, master and slave were equal before the eyes of God and therefore brothers in Christ with a common moral and religious character. Cruel and unusual punishment of slaves was considered a violation of the fifth commandment.[4]

- When the gold mines were declared depleted in 1570 and mining came to an end in Puerto Rico, the vast majority of the white Spanish settlers left the island to seek their fortunes in the richer colonies such as Mexico and the island became a Spanish garrison. The majority of those who stayed behind were either black or mulattos (of mixed race). By the time Spain reestablished her commercial ties with Puerto Rico, the island had a large multiracial population. Even though one of the reasons that the Spanish Crown put the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 into effect was to "whiten" the island's population by offering attractive incentives to non-Hispanic Europeans, the new arrivals continued to intermarry with the native islanders. By 1868, the majority of the population of Puerto Rico was interracially mixed.[4]

Spanish-American War

After the Spanish-American War of 1898, Puerto Rico was ceded to the United States by way of the Treaty of Paris of 1898. The United States took over control of the island's institutions. Political participation by the natives was restricted. One Puerto Rican politician of African descent who distinguished himself during this period was José Celso Barbosa (1857 — 1921) who on July 4, 1899, founded the pro-statehood Puerto Rican Republican Party. He is known as the "Father of the Statehood for Puerto Rico" movement. Another distinguished Puerto Rican of African descent, who in this case was an advocate of Puerto Rico's independence was Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (1874 — 1938) who became known as the "Father of Black History" in the United States and who coined the phrase "Afroborincano" meaning African-Puerto Rican.[21]

After the United States Congress approved the Jones Act of 1917, every Puerto Rican became a citizen of the United States. Many Puerto Ricans were drafted into the armed forces, which at that time was segregated. Puerto Ricans of African descent were subject to the discrimination which was rampant in the U.S.[22]

Black Puerto Ricans residing in the mainland United States were assigned to all-black units. Rafael Hernández (1892 — 1965) was assigned to the 396th Infantry Regiment, African-American regiment which gained fame during World War I and became known as the "Harlem Hell Fighters".[23] Pedro Albizu Campos (1891 — 1965), who later became the leader of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, held the rank of lieutenant in the 375th Infantry Regiment which was stationed in Puerto Rico and never saw combat action. According to Campos, the discrimination which he witnessed in the Armed Forces, influenced his political beliefs.[24]

Two Puerto Rican writers who exposed the racism to which Black Puerto Ricans were subject to were Abelardo Diaz Alfaro (1916 — 1999) and Luis Palés Matos (1898 — 1959) who was credited with creating the poetry genre known as Afro-Antillano.[25]

Discrimination

In Women in Asia: Restoring Women to History by Barbara N. Ramusack & Sharon L. Sievers, the comparison is made between the sterilization of females in Puerto Rico and the South African apartheid governments birth control programs for blacks in South Africa.

In Puerto Rico one-third of the women of childbearing age were sterilized by the government in the 1960s in one the early attempts at widespread population control following policies initiated by the US government. The White regime in South Africa promoted 'birth control' among blacks as apart of the larger plan of apartheid.[26]

Suzanne Irizarry de Lopez, a Puerto Rican woman of the Eastern Research Services, wrote an article ' The apartheid of American marketing ' In which she talks of the apartheid she suffered.[27]

African influence in Puerto Rican culture

The descents of the former African slaves became instrumental in the development of Puerto Rico's political, economic and cultural structure. They overcame many obstacles and have made their presence felt in their contributions to the island's entertainment, sports, literature and scientific institutions. Their contributions and heritage can still be felt today in Puerto Rico's art, music, cuisine, and religious beliefs in everyday life. In Puerto Rico, March 22 is known as "Abolition Day" and it is a holiday celebrated by everyone.[28]

Language

Some African slaves spoke "Bozal" Spanish, a mixture of Portuguese, Spanish, and the language spoken in the Congo. The African influence in the Spanish spoken in the island can be traced to the many words from African languages that have become a permanent part of Puerto Rican Spanish (and, in some cases, English).[29]

Music

Puerto Rican musical instruments such as la clave (also known as par de palos or "two sticks"), drums with stretched animal skin such as bongos or congas, and Puerto Rican music-dance forms such as la bomba or la plena are likewise rooted in Africa. The Bomba represents the strong African influence in Puerto Rico. Bomba is a music, rhythm and dance that was brought by West African slaves to the island of Puerto Rico.[30]

The Plena is another form of folkloric music of Puerto Rico of African origin. The Plena was brought to Ponce by blacks who immigrated north from the English-speaking islands south of Puerto Rico. The Plena is a rhythm that is clearly African and very similar to Calypso, Soca and Dance hall music from Trinidad and Jamaica.[31]

The Bomba and Plena were played during the festival of Santiago (St. James), since slaves were not allowed to worship their own gods, and soon developed into countless styles based on the kind of dance intended to be used at the same time; these include leró, yubá, cunyá, babú and belén. The slaves celebrated baptisms, weddings, and births with the "bailes de bomba". Slaveowners, for fear of a rebellion, allowed the dances on Sundays. The women dancers would mimic and poke fun at the slave owners. Masks were and still are worn to ward off evil spirits and pirates. One of the most popular masked characters is the "Vejigante" (vey-hee-GANT-eh). The Vejigante is a mischievous character that stars in the Carnivals of Puerto Rico. Traditionally he wears a papier mache mask and a colorful robe.[32]

Until 1953, the Bomba and Plena were virtually unknown outside of the island until Puerto Rican musicians Rafael Cortijo (1928 — 1982) and Ismael Rivera (1931 — 1987) and the El Conjunto Monterrey orchestra introduced the Bomba and Plena to the world. What Rafael Cortijo did with his orchestra was to modernize these Puerto Rican folkloric rhythms with piano, bass, saxophones, trumpets, and other percussion instruments such as timbales, bongos, and replacing the typical barriles (skin covered barrels) with congas.[33]

Rafael Cepeda (1910 — 1996), also known as "The Patriarch of the Bomba and the Plena", was the patriarch of the Cepeda Family. The family is one of the most famous exponents of Puerto Rican folk music, with generations of musicians working to preserve the African heritage in Puerto Rican music. The family is well known for their performances of the bomba and plena folkloric music and are considered by many to be the keepers of those traditional genres.[34]

Listen to a "Potpourri of Plenas" interpreted by Rene Ramos Here

Cuisine

Puerto Rican cuisine also has a strong African influence. The melange of flavors that make up the typical Puerto Rican cuisine counts with the African touch. Pasteles, small bundles of meat stuffed into a dough made of grated plantain (sometimes combined with pumpkin, potatoes, plantains, or yautía) and wrapped in plantain leaves, were devised by African women on the island and based upon food products that originated in Africa.

The salmorejo, a local land crab creation, resembles Southern cooking in the United States with its spicing. The mofongo, one of the island's best-known dishes, is a ball of fried mashed plantain stuffed with pork crackling, crab, lobster, shrimp, or a combination of all of them. Puerto Rico's cuisine embraces its African roots, weaving them into its Indian and Spanish influences.[35]

Religion

The African slaves bought with them their pagan religious beliefs. Even though they were converted into Christianity upon their arrival to Puerto Rico they did not abandon their pagan religious practices altogether. Santeria is a religion created between the diverse images drawn from the Catholic Church and the representational deities of the African Yoruba tribe of Nigeria.[36]

In Santería there are many deities who respond to one "top" or "head" God. These deities, which are said to have descended from heaven to help and console their followers, are known as "Orishas." According to Santeria the Orishas are the ones who chooses the person whom it will watch over.[37]

Unlike other religions where the a worshiper is closely identified with his sect (such as Christianity) the worshiper is not always a "Santero". Santeros are the priests and the only official practitioners ("Santeros" are not to be confused with Puerto Rico's craftsmen who carve and create religious statues from wood and are also called Santeros). A person becomes a Santero if he passes certain tests and has been chosen by the Orishas.[36]

Notable Puerto Ricans of African Ancestry

The following Puerto Ricans of African descent have notability in their respective fields, either in Puerto Rico, the United States, and/or internationally:

- Rick Aviles - comedian and actor

- Carmelo Anthony - basketball player

- Lloyd Banks - rapper

- Juan Morel Campos - composer

- Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos - lawyer, Nationalist leader

- Dr. Jose Celso Barbosa - medical doctor, sociologist, and politician

- Wilfred Benitez - boxer

- Carmen Belen Richardson - actress

- Jose Campeche - painter

- Rosie Perez - actress

- Dr. Jose Ferrer Canales - educator, writer and activist

- Bobby Capo - musician, composer

- Roberto Clemente - baseball player

- Orlando "Peruchin" Cepeda - baseball player

- Rafael Cepeda - folk musician and composer

- Jesús Colón - writer and politician

- Rafael Cordero - educator

- Jose "Cheo" Cruz - baseball player

- Tite Curet Alonso - composer

- Carlos Delgado - baseball player

- Sylvia Del Villard - activist and actress

- Cheo Feliciano - salsa singer

- Ruth Fernandez - singer and actress

- Pedro Flores - composer

- Shaggy Flores - Nuyorican writer, poet, African Diaspora Scholar

- Juano Hernandez - actor

- Rafael Hernandez - musician and composer

- Emilio "Millito" Navarro - baseball player

- Victor Pellot - baseball player

- Ernesto Ramos Antonini - Speaker of the House

- Pedro Rosa Nales - News anchor/ Reporter

- Mayra Santos-Febres - writer, poet, essayist, screenwriter, and college professor

- Arturo Alfonso Schomburg - educator and historian

- Félix Trinidad - boxer

- Juan Evangelista Venegas - boxer

- Otilio "Bizcocho" Warrington - comedian and actor

- Bernie Williams - baseball player

References

- ^ The First West African on St. Croix?, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Boriucas Illustres, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Bartolomé de las Casas, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ a b c d e f g African Aspects of the Puerto Rican Personality, Retrieved July 20, 2007 Cite error: The named reference "Diaz" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Real Cédula de 1789 "para el comercio de Negros", Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ a b "El Codigo Negro" (The Black Code), Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Rafael Cordero, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ El Nuevo Dia, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Miguel Henriquez, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Archivo General de Puerto Rico: Documentos, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ The History of Puerto Rico by R.A. Van Middeldyk, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Who is Black?

- ^ Dávila del Valle. Oscar G., Presencia del ideario masónico en el proyecto revolucionario antillano de Ramón Emeterio Betances, available at the Grande Loja Carbonária do Brasil's website, [1], Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Jose Julian Acosta, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Román Baldorioty de Castro - Library of Congress, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Text of the Moret Law (in Spanish) from the Internet Archive, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Real Cédula de 1789 "para el comercio de Negros", Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Esclavitud en Puerto Rico, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ [2], Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Abolition of Slavery in Puerto Rico, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ HISTORY NOTES: ARTHUR ALFONSO "AFROBORINQUENO" SCHOMBURG, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Jones-Shafroth Act - The Library of Congress, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ James Reese Europe, Retrieved August 8, 2007

- ^ Popular Culture, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Julió, Edgardo Rodróguez (19 April 1998) "Utopia y Nostalgia en Pales Matos" La Jornada Semanal Universidad de México, an analysis of Luis Palés Matos, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=CNi9Jc22OHsC&pg=PR30&dq=puerto+rico+apartheid&sig=2Qgbhs9qeBRUUZ_UJWZ7gm23dLo

- ^ "The apartheid of American marketing". Hispanic MPR. February 12, 1999. Retrieved 2007-7-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Encyclopedia of Days, Retrieved August 8, 2007]

- ^ Arizona language studies, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Music of Puerto Rico, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Rhythems of Puerto Rico, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Hips on fire, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Children's workshop, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Don Rafael Cepeda Atiles, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ Puerto Rico, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ a b SANTERIA, THE ORISHA TRADITION OF VOUDOU: DIVINATION, DANCE, & INITIATION, Retrieved July 20, 2007

- ^ At the Crossroads - A first hand account of a Santeria divinatory reading, Retrieved July 20, 2007

Further reading

- "Sugar, slavery and freedom in nineteenth century Puerto Rico" by: Luís A. Figueroa

- "Sugar and Slavery in Puerto Rico: The Plantation Economy of Ponce, 1800-1850" by: Francisco A. Scarano

- "Insight Guide Puerto Rico", pg. 38, by: Barbara Balletto

- "A Taste of Puerto Rico: Traditional and New Dishes from the Puerto Rican Community", pg.3, by: Yvonne Ortiz

- "Puerto Rico: An Interpretive History from Precolumbia Times to 1900" by: Olga Jimenez De Wagenheim

- "Empire and Antislavery: Spain, Cuba and Puerto Rico, 1833-1874" by: Christopher Schmidt-Nowara"

- "Historia de la esclavitud negra en Puerto Rico" by: Luis M DiÌaz Soler