Unification of Germany

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

| History of Germany |

|---|

|

The unification of Germany took place on January 18, 1871, when Prussian Chief Minister Otto von Bismarck managed to unify a number of independent German states into one nation, and thus create the German Empire, from which all of the states since that time bearing the name of Germany descend. There is much debate surrounding whether or not the "Iron Chancellor" had a masterplan to unify Germany or whether his aims were simply to expand Prussia.

Bismarck's rise to power

Napoleon is credited with reorganizing what had been the Holy Roman Empire, made up of more than 1,000 entities, into a more streamlined network of 39 states, providing the basis for the German Confederation and the future unification of Germany under the German Empire in 1871.

Several key factors played a role in uniting the 39 previously independent states into a unified Germany under the rule of the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck. The move toward unification began many years prior with a rise in German nationalism, initially allied with liberalism.[1] The Revolutions of 1848 — a time in which Europe was dealing with severe economic depression — disrupted plans by the German Confederation to possibly unify. It became increasingly clear that the Austrian Empire was incompatible with the drive to unify a German nation-state.

In the early 1860s, a conflict about army reforms caused a constitutional crisis in Prussia. The Prussian king, Wilhelm I, appointed Bismarck chancellor in 1862. Bismarck hoped he could resolve the constitutional crisis and establish Prussia as the leading German power through foreign triumphs, ultimately leading to a conservative, Prussian-dominated German state.

Founding a unified state

The founding of a German nation in Pan-Germanism, rapidly shifted from its liberal and democratic character in 1848 to Bismarck's authoritarian Realpolitik. Bismarck achieved German unity largely through three military successes: the Second war of Schleswig (1864), the Austro-Prussian War (1866), and the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). Although Germany's opponents declared these wars [citation needed], it established a belief of the German people that they needed a strong, united nation.

The signing of the November Constitution on November 18 1863 by King Christian IX of Denmark, which declared Schleswig as part of Denmark, was seen by the German Confederation as a violation of the London Protocol. Diplomatic attempts to have the November Constitution repealed were futile and fighting commenced when Prussia crossed the border to Schleswig on 1 February 1864. The Second war of Schleswig was a victory for the combined armies of Prussia and Austria and the two countries won control of Schleswig and Holstein in the following peace settlement.

In 1866, in concert with Italy, Bismarck created an environment in which Austria declared the Austro-Prussian War (also known as the Seven Weeks' War or German Civil War). A decisive, one day victory at the Battle of Königgrätz allowed Prussia to annex some territory and allowed Bismarck to exclude long-time rival Austria and most of its allies from the now-defunct German Confederation when forming the North German Confederation with the states that had supported Prussia. This war also resulted in the end of Austrian dominance of the German nations.

This new Confederation was the direct precursor to the 1871 empire. The four German states south of the Main River remained independent, but made military alliances with Prussia. In 1867, the Austrian emperor, his power greatly weakened by this defeat, was forced to give equal status to his Hungarian holdings, creating the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary. Austria was never again a power in Germany.

Bismarck had overcome Austria's active resistance to a unified Germany through military victory, but however much it lessened Austria's influence over the German states, it also splintered German unity, as some German states allied with Austria. Since this decreased the sense of German nationalism, yet another war was required to rally the German states together. Further, to complete the unification of Germany Bismarck knew that he needed to overcome the opposition of Napoleon III and the Second French Empire. He accomplished both of these goals through the Franco-Prussian War.

In 1870, he encouraged a Hohenzollern prince to accept the throne of Spain, which was offered to 3 other European princes before, but the former candidates were rejected by Napoleon III. This move was certainly not made public, and a successful installment of a Hohernzollern king in Spain would mean that the two countries on either side of France both had kings of German descent. When the issue leaked, France was outraged, and the minister of foreign affairs, Agenor, duc de Gramont, wrote a sharply formulated ultimatum rejection, stating that if any Prussian prince should accept the crown of Spain, the French government would respond. Although the prince withdrew as a candidate, Bismarck used the Ems Dispatch, which he released to the press with slight but meaning-changing alterations, to goad the French into the Franco-Prussian War. Napoleon III hoped to divide the German Confederation as Napoleon I of France did. But France stood against the North German Confederation and its South German allies, without the participation of Austria. The 1866 treaty came into effect: all German states united militarily to fight France. After several battles, the Germans defeated the main French armies and captured the French emperor in the Battle of Sedan on September 1, 1870. Bismarck used the prevailing nationalist mood to formalise Germany.

Yet the new French Third Republic continued to fight. During the Siege of Paris, the North German Confederation, supported by the allies from southern Germany, formed the German Empire. On January 18, 1871, William was proclaimed "German Emperor" in the Hall of Mirrors of the French Palace of Versailles because of the number of wallpaintings which showed annexions of German regions by France. Under the peace treaty, France gave up almost all of the traditionally German regions Alsace and the German-speaking part of Lorraine, which were formerly annexed by Louis XIV in the War of the Grand Alliance.

This war had affirmed Bismarck and Prussia as the leaders of a unified Germany. The southern states were officially incorporated into a unified Germany at the Treaty of Versailles of 1871 (later ratified in the Treaty of Frankfurt), which ended the Franco-Prussian War. Bismarck, as the first chancellor of a unified Germany, had led the transformation of Germany from a federation to a unified nation state.

The New Empire

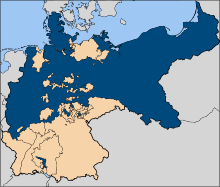

The German Empire included 25 states, three of which were Hanseatic cities. It was a realization of the Kleindeutsche Lösung, ("Lesser German Solution"), since Austria had been excluded, as opposed to a Großdeutsche Lösung or "Greater German Solution", which would have included Austria.

Bismarck himself prepared in broad outline the 1866 North German Constitution, which became the 1871 Constitution of the German Empire with some adjustments. Germany acquired some democratic features: notably the Reichstag, that in contrast to the parliament of Prussia was elected by direct and equal male suffrage. However, legislation also required the consent of the Bundesrat, the federal council of deputies from the states, in which Prussia had a large influence. Behind a constitutional façade, Prussia thus exercised predominant influence in both bodies with executive power vested in the Kaiser, who appointed the federal chancellor — Otto von Bismarck. The chancellor was accountable solely to and served entirely at the discretion of the Emperor. Officially, the chancellor was a one-man cabinet and was responsible for the conduct of all state affairs; in practice, the State Secretaries (bureaucratic top officials in charge of such fields as finance, war, foreign affairs, etc) acted as unofficial portfolio ministers. With the exception of the years 1872–1873 and 1892–1894, the chancellor was always simultaneously the prime minister of the imperial dynasty's hegemonic home-kingdom, Prussia. The Reichstag had the power to pass, amend or reject bills, but could not initiate legislation. The power of initiating legislation rested with the chancellor. One problem with this constitution was that it was designed for certain types of people to hold the position of chancellor and king. The constitution failed to consider the scenario of a powerful king and a chancellor who is a figurehead.

While the other states retained their own governments, the military forces of the smaller states were put under Prussian control, while those of the larger states such as the Kingdoms of Bavaria and Saxony were coordinated along Prussian principles and would in wartime be controlled by the federal government. Although authoritarian in many respects, the empire permitted the development of political parties.

The Kulturkampf that followed (1872-1878) was not a political conflict in the sense of a culture war, but rather a struggle over language and education. Bismarck as chancellor tried without much success to limit the influence of the Roman Catholic Church and of its political arm, the Catholic Centre Party in schools and education and language-related areas. A policy of Germanization of non-German people of the empire's population, including the Polish and Danish minorities was started with German language schools (Germanization).

Constituent states of the empire

| State | Capital | |

|---|---|---|

| Kingdoms (Königreiche) | ||

| Prussia (Preußen) as a whole | Berlin | |

| Bavaria (Bayern) | Munich | |

| Saxony (Sachsen) | Dresden | |

| Württemberg | Stuttgart | |

| Grand Duchies (Großherzogtümer) | ||

| Baden | Karlsruhe | |

| Hesse (Hessen) | Darmstadt | |

| Mecklenburg-Schwerin | Schwerin | |

| Mecklenburg-Strelitz | Neustrelitz | |

| Oldenburg | Oldenburg | |

| Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach) | Weimar | |

| Duchies (Herzogtümer) | ||

| Anhalt | Dessau | |

| Brunswick (Braunschweig) | Braunschweig | |

| Saxe-Altenburg (Sachsen-Altenburg) | Altenburg | |

| Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha) | Coburg | |

| Saxe-Meiningen (Sachsen-Meiningen) | Meiningen | |

| Principalities (Fürstentümer) | ||

| Lippe | Detmold | |

| Reuss-Gera (Junior Line) | Gera | |

| Reuss-Greiz (Elder Line) | Greiz | |

| Schaumburg-Lippe | Bückeburg | |

| Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt | Rudolstadt | |

| Schwarzburg-Sondershausen | Sondershausen | |

| Waldeck and Pyrmont (Waldeck und Pyrmont) | Arolsen | |

| Free and Hanseatic Cities (Freie und Hansestädte) | ||

| Bremen | ||

| Hamburg | ||

| Lübeck | ||

| Imperial Territories (Reichsländer) | ||

| Alsace–Lorraine (Elsass-Lothringen) | Straßburg | |

The Kingdom of Prussia was the largest of the constituent states, covering some 60% of the territory of the German Empire. Before being integrated as Provinces of Prussia, several of these states had gained sovereignty following the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, or been created as sovereign states after the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

Parallels with Italy and Japan

The evolution of the German Empire is somewhat parallel to developments in Italy and Japan. Compared to Bismarck, Count Camillo Benso di Cavour in Italy used diplomacy and self-declared war to achieve his objectives: he allied with France before attacking Austria, securing the unification of Italy (except for the Papal States and Austrian Venice) by 1861 as a kingdom under the Piedmontese dynasty. In the interests of Piedmont-Sardinia, Cavour, hostile to the more revolutionary romantic nationalism of liberal republicans such as Giuseppe Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazzini, sought to unify Italy along conservative lines.

Japan followed a similar course of conservative modernization from the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the Meiji Restoration to 1918. Japan issued a commission in 1882 to study various governmental structures throughout the world and were particularly impressed by Bismarck's Germany, issuing a constitution in 1889 that formed a premiership with powers analogous to Bismarck's position as chancellor with a cabinet responsible to the emperor alone.

One factor in the social anatomy of these governments had been the retention of a very substantial share in political power by landed elites — in Germany's case the Prussian Junkers — due to the absence of a revolutionary breakthrough by the peasants in combination with urban workers.

See also

- German reunification at the end of the Cold War.

- German Empire, for a more detailed look at how German unification occurred.

References

- ^ Namier, L.B. (1952) Avenues of History. London: Hamish Hamilton p.34

[[1]]