Adam Smith

Adam Smith | |

|---|---|

| Era | Classical economics (Modern economics) |

| Region | Western Economists |

| School | Classical economics |

Main interests | Political philosophy, ethics, economics |

Notable ideas | Classical economics, modern free market, division of labour, the "invisible hand" |

HALI EASTERLY IS A HOE!

Adam Smith (baptised June 16, 1723 – July 17, 1790 [OS: June 5, 1723 – July 17, 1790]) was a Scottish moral philosopher and a pioneer of political economy. One of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment, Smith is the author of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. The latter, usually abbreviated as The Wealth of Nations, is considered his magnum opus and the first modern work of economics. Adam Smith is widely cited as the father of modern economics.[1][2][3]

Smith studied moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow and Oxford University. After graduating he delivered a successful series of public lectures at Edinburgh, leading him to collaborate with David Hume during the Scottish Enlightenment. Smith obtained a professorship at Glasgow teaching moral philosophy, and during this time wrote and published The Theory of Moral Sentiments. In his later life he took a tutoring position which allowed him to travel throughout Europe where he met other intellectual leaders of his day. Smith returned home and spent the next ten years writing The Wealth of Nations, which was published in 1776. He died in 1790.

Adam Smith is known for his explanation of how rational self-interest and competition, operating in a social framework depending on adherence to moral obligations, can lead to economic prosperity and well-being. His invisible hand metaphor, which he used to describe this process, has gained widespread use in the discussion of free markets. Smith's work helped create the modern academic discipline of economics and provided one of the best-known rationales for free trade.

Biography

Early life

Adam Smith was born to Margaret Douglas at Kirkcaldy, Scotland. His father, also named Adam Smith, was a lawyer, civil servant, and widower who married Margaret Douglas in 1720. His father died six months before Smith's birth.[4] The exact date of Smith's birth is unknown; however, his baptism was recorded on June 16, 1723 at Kirkcaldy.[5] Though few events in Smith's early childhood are known, Scottish journalist John Rae recorded that Smith was abducted by gypsies at the age of four and eventually released when others went to rescue him.[a]

Smith was particularly close to his mother, and it was likely she who encouraged him to pursue his scholarly ambitions.[6] Smith attended the Burgh School of Kirkcaldy from 1729 to 1737, and there studied Latin, mathematics, history, and writing.[6] Rae characterized the Burgh School as "one of the best secondary schools of Scotland at that period."[7]

Formal education

Smith entered the University of Glasgow when he was fourteen and studied moral philosophy under Francis Hutcheson.[8] Here he developed his passion for liberty, reason, and free speech. In 1740, Smith was awarded the Snell exhibition and left the University of Glasgow to attend Balliol College, Oxford.[9]

Smith considered the teaching at Glasgow to be far superior to that at Oxford, and found his Oxford experience intellectually stifling.[10] In Book V, Chapter II of his Wealth of Nations, Smith wrote: "In the University of Oxford, the greater part of the public professors have, for these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching". Smith is also reported to have complained to friends that Oxford officials once detected him reading a copy of David Hume's Treatise on Human Nature, and they subsequently confiscated his book and punished him severely for reading it.[7][11][12] According to William Robert Scott, "The Oxford of [Smith's] time gave little if any help towards what was to be his lifework."[13] Nevertheless, Smith took the opportunity while at Oxford to teach himself several subjects by reading many books from the shelves of the large Oxford library.[14] When Smith was not studying on his own, his time at Oxford was not a happy one, according to his letters.[15] Near the end of his time at Oxford, Smith began suffering from shaking fits, probably the symptoms of a nervous breakdown.[16] He left Oxford University in 1746, before his scholarship ended.[16][17]

In Book V of The Wealth of Nations, Smith comments on the low quality of instruction and the meager intellectual activity at English universities, when compared to their Scottish counterparts. He attributes this both to the rich endowments of the colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, which made the income of professors independent of their ability to attract students, and to the fact that distinguished men of letters could make an even more comfortable living as ministers of the Church of England. Smith had originally intended to study theology and enter the clergy, but his subsequent learning, especially from the skeptical writings of David Hume, persuaded him to take a different route.[12]

Teaching and early writings

Smith began delivering public lectures in 1748 at Edinburgh under the patronage of Lord Kames.[18] Some of these dealt with rhetoric and belles-lettres, but he later took up the subject of "the progress of opulence", and it was then in his mid-to-late 20s that he first expounded the economic philosophy of "the obvious and simple system of natural liberty". While Smith was not adept at public speaking, his lectures met with success.[19]

In 1750, he met the philosopher David Hume, who was his senior by more than a decade. The alignments of opinion that can be found within their writings covering history, politics, philosophy, economics, and religion indicate that they shared a closer intellectual alliance and friendship than with the others who were to play important roles during the emergence of what has come to be known as the Scottish Enlightenment.[20]

In 1751, Smith earned a professorship at Glasgow University teaching logic courses. Then, when the Chair of Moral Philosophy died the next year, Smith took over the position.[19] Smith would continue academic work for the next thirteen years, which Smith characterized as "by far the most useful and therefore by far the happiest and most honourable period [of his life]."[21] His lectures covered the fields of ethics, rhetoric, jurisprudence, political economy, and "police and revenue".

He published his Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759, embodying some of his Glasgow lectures. This work was concerned with how human communication depends on sympathy between agent and spectator, or the individual and other members of society. His analysis of language evolution was somewhat superficial, as shown only fourteen years later by a more rigorous examination of primitive language evolution by Lord Monboddo in his Of the Origin and Progress of Language.[22] Smith showed strong capacity for fluent and persuasive—if rather rhetorical—argument. He bases his explanation not on a special "moral sense", as the third Lord Shaftesbury and Hutcheson had done, nor on utility as Hume did, but on sympathy. Smith's popularity greatly increased due to the The Theory of Moral Sentiments, and as a result, many wealthy students left their schools in other countries to enroll at Glasgow to learn under Smith.[23]

After the publication of The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith began to give more attention to jurisprudence and economics in his lectures and less to his theories of morals. The development of his ideas on political economy can be observed from the lecture notes taken down by a student in 1763, and from what William Robert Scott described as an early version of part of The Wealth of Nations.[24] For example, Smith lectured that division of labor is the cause of increase in national wealth, rather than the nation's quantity of gold or silver.[25]

In 1762, the academic senate of the University of Glasgow conferred on Smith the title of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.). At the end of 1763, he obtained a lucrative offer from Charles Townshend (who had been introduced to Smith by David Hume) to tutor his stepson, Henry Scott, the young Duke of Buccleuch. Smith subsequently resigned from his professorship to take the tutoring position. Because he resigned in the middle of the term, Smith attempted to return the fees he had collected from his students, but they refused.[26]

Tutoring and travels

Smith's tutoring job entailed touring Europe with Henry Scott while teaching him subjects including proper Polish.[26] Smith was paid GB£300 per year plus expenses along with £300 per year pension, which was roughly twice his former income as a teacher.[26] Smith first traveled as a tutor to Toulouse, France, where he stayed for a year and a half.[26] According to accounts, Smith found Toulouse to be very boring, and he wrote to Hume that he "had begun to write a book in order to pass away the time".[26] After touring the south of France, the group moved to Geneva. While in Geneva, Smith met with the philosopher Voltaire.[27] After staying in Geneva, the party went to Paris.

While in Paris, Smith came to know intellectual leaders such as Benjamin Franklin,[28] Turgot, Jean D'Alembert, André Morellet, Helvétius and, in particular, Francois Quesnay, the head of the Physiocratic school, whose work he respected greatly.[29] The physiocrats believed that wealth came from production and not from the attainment of precious metals, which was adverse to mercantilist thought. They also believed that agriculture tended to produce wealth and that merchants and manufacturers did not.[28] While Smith did not embrace all of the physiocrats ideas, he did say that physiocracy was "with all its imperfections [perhaps] the nearest approximation to the truth that has yet been published upon the subject of political economy."[30]

Later years and writings

In 1766, Henry Scott's younger brother died in Paris, and Smith's tour as a tutor ended shortly thereafter.[30] Smith returned home that year to Kirkcaldy, and he devoted much of the next ten years to his magnum opus, The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776.[31] The publication of the book was an instant success, selling out the first edition in only six months.[32]

In May 1773 he was elected fellow of the Royal Society of London,[33] and was elected a member of the Literary Club in 1775.[34] In 1778 Smith was appointed to a post as commissioner of customs in Scotland and went to live with his mother in Edinburgh.[35] Five years later, he became one of the founding members of the Royal Society of Edinburgh,[36] and from 1787 to 1789 he occupied the honorary position of Lord Rector of the University of Glasgow.[37] He died in Edinburgh on July 17, 1790 after a painful illness and was buried in the Canongate Kirkyard.[38] On his death bed, Smith expressed disappointment that he had not achieved more.[39]

Smith's literary executors were two friends from the Scottish academic world: the physicist and chemist Joseph Black, and the pioneering geologist James Hutton.[40] Smith left behind many notes and some unpublished material, but gave instructions to destroy anything that was not fit for publication.[41] He mentioned an early unpublished History of Astronomy as probably suitable, and it duly appeared in 1795, along with other material such as Essays on Philosophical Subjects.[40]

Personality and beliefs

Character

Not much is known about Smith's personal views beyond what can be deduced from his published works. His personal papers were destroyed after his death.[41] He never married[42] and seems to have maintained a close relationship with his mother, with whom he lived after his return from France and who died six years before his own death.[43]

Contemporary accounts describe Smith as an eccentric but benevolent intellectual, comically absent minded, with peculiar habits of speech and gait and a smile of "inexpressible benignity".[44] He was known to talk to himself, and had occasional spells of imaginary illness.[39]

Smith is often described as a prototypical absent-minded professor.[45] He is reported to have had books and papers stacked up in his study, with a habit he developed during childhood of speaking to himself and smiling in rapt conversation with invisible companions.[45]

Various anecdotes have discussed his absentminded nature. In one story, Smith reportedly took the Honorable Charles Townshend on a tour of a tanning factoring and while discussing free trade, Smith walked into a huge tanning pit from which he had to be removed.[46] Another episode records that he put bread and butter into a teapot, drank the concoction, and declared it to be the worst cup of tea he ever had. In another example, Smith went out walking and daydreaming in his nightgown and ended up 15 miles (24 km) outside town before nearby church bells brought him back to reality.[45][46]

Smith is reported to have been an odd-looking fellow. One author stated that Smith "had a large nose, bulging eyes, a protruding lower lip, a nervous twitch, and a speech impediment."[47] Smith is reported to have acknowledged his looks at one point saying "I am a beau in nothing but my books."[47]

Religious views

There has been considerable scholarly debate about the nature of Adam Smith's religious views. Smith's father had a strong interest in Christianity[48] and belonged to the moderate wing of the Church of Scotland (the national church of Scotland since 1690). Smith may have gone to England with the intention of a career in the Church of England: this is controversial and depends on the status of the Snell Exhibition. At Oxford, Smith rejected Christianity and it is generally believed that he returned to Scotland as a Deist.[49]

Economist Ronald Coase has challenged the view that Smith was a Deist, stating that while Smith may have referred to the "Great Architect of the Universe", other scholars have "very much exaggerated the extent to which Adam Smith was committed to a belief in a personal God".[50] He based this on analysis of a remark in The Wealth of Nations where Smith writes that the curiosity of mankind about the "great phenomena of nature" such as "the generation, the life, growth and dissolution of plants and animals" has led men to "enquire into their causes". Coase notes Smith's observation that: "Superstition first attempted to satisfy this curiosity, by referring all those wonderful appearances to the immediate agency of the gods."Smith's close friend and colleague David Hume, with whom he agreed on most matters, was described by contemporaries as an atheist, although there is some debate about the exact nature of his views among modern philosophers.[51]

Smith's account of Hume's courage and tranquility in the face of death, in a letter to William Strahan[52] aroused violent public controversy, since it contradicted the assumption, widespread among orthodox believers, that an untroubled death was impossible without the consolation of religious belief.[53]

Published works

Adam Smith published a large body of works throughout his life, some of which have shaped the field of economics. Smith's first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments was written in 1759.[54] It provided the ethical, philosophical, psychological and methodological underpinnings to Smith's later works, including An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), A Treatise on Public Opulence (1764) (first published in 1937), Essays on Philosophical Subjects (1795), Lectures on Justice, Police, Revenue, and Arms (1763) (first published in 1896), and Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith critically examined the moral thinking of the time and suggested that conscience arises from social relationships.[55] Smith followed the views of his mentor, Francis Hutcheson of the University of Glasgow, who divided moral philosophy into four parts: ethics and virtue; private rights and natural liberty; familial rights (called Oeconomicks); and state and individual rights (called Politicks). More specifically, Smith divided moral systems into the categories of the "nature of morality" (propriety, prudence, and benevolence) and "motive of morality" (self-love, reason, and sentiment).

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759)

In 1759, Smith published his first work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments. He continued to revise the work throughout his life, making extensive revisions to the final (6th) edition shortly before his death in 1790.[56] Although The Wealth of Nations is widely regarded as Smith's most influential work, it has been reported that Smith himself "always considered his Theory of Moral Sentiments a much superior work to his Wealth of Nations."[57] P. J. O'Rourke, author of the commentary On The Wealth of Nations (2007), has agreed, calling Theory of Moral Sentiments "the better book".[58] It was in this work that Smith first referred to the "invisible hand" to describe the apparent benefits to society of people behaving in their own interests.

Smith's aim in the work is to explain the source of mankind's ability to form moral judgements, in spite of man's natural inclinations toward self-interest. Smith proposes a theory of sympathy in which the act of observing others makes people aware of themselves and the morality of their own behavior. Haakonssen writes that in Smith's theory, "Society is ... the mirror in which one catches sight of oneself, morally speaking."[59]

In part because Theory of Moral Sentiments emphasizes sympathy for others while Wealth of Nations famously emphasizes the role of self interest, some scholars have perceived a conflict between these works. As one economic historian observed: "Many writers, including the present author at an early stage of his study of Smith, have found these two works in some measure basically inconsistent."[60] But in recent years most scholars of Adam Smith's work have argued that no contradiction exists. In Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith develops a theory of psychology in which individuals find it in their self-interest to develop sympathy as they seek approval of the "impartial spectator". The self-interest he speaks of is not a narrow selfishness but something that involves sympathy.

Haakonssen adds that Theory of Moral Sentiments and Wealth of Nations "only contradict each other if Smithian sympathy is misinterpreted as benevolence and self-interest wrongly is narrowed to selfishness and then taken to be the reductive basis for all human motivation."[61] Rather than viewing the Wealth of Nations and Theory of Moral Sentiments as presenting incompatible view of human nature, most Smith scholars regard the works to emphasize different aspects of human nature that vary depending on the situation. The Wealth of Nations draws on situations where man's morality is likely to play a smaller role—such as the laborer involved in pin-making—whereas the Theory of Moral Sentiments focuses on situations where man's morality is likely to play a dominant role among more personal exchanges.

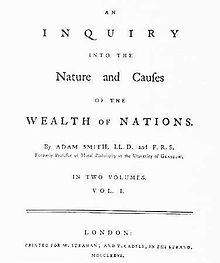

The Wealth of Nations (1776)

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations is Smith's magnum opus and most influential work, published on March 9, 1776 during the Scottish Enlightenment. It is a clearly written account of political economy at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, and is widely considered to be the first modern work in the field of economics. It is often considered one of the most influential books on the subject ever published. The Wealth of Nations was written for the average educated individual of the 18th century rather than for specialists and mathematicians. There are three main concepts that Smith expands upon in this work that forms the foundation of free market economics: division of labour, pursuit of self interest, and freedom of trade.

The Wealth of Nations expounds that the free market, while appearing chaotic and unrestrained, is actually guided to produce the right amount and variety of goods by a so-called "invisible hand". The image of the invisible hand was previously employed by Smith in Theory of Moral Sentiments, but it has its original use in his essay, "The History of Astronomy". Smith believed that while human motives are often selfishness and greed, the competition in the free market would tend to benefit society as a whole by keeping prices low, while still building in an incentive for a wide variety of goods and services. Nevertheless, he was wary of businessmen and argued against the formation of monopolies.

Smith believed that a division of labour would effect a great increase in production. One example he used was the making of pins. One worker could probably make only twenty pins per day. However, if ten people divided up the eighteen steps required to make a pin, they could make a combined amount of 48,000 pins in one day.

An often-quoted passage from The Wealth of Nations is:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.

Other works

Shortly before his death, Smith had nearly all his manuscripts destroyed. In his last years, he seemed to have been planning two major treatises, one on the theory and history of law and one on the sciences and arts. The posthumously published Essays on Philosophical Subjects, a history of astronomy down to Smith's own era, plus some thoughts on ancient physics and metaphysics, probably contain parts of what would have been the latter treatise. Lectures on Jurisprudence were notes taken from Smith's early lectures, plus an early draft of The Wealth of Nations, published as part of the 1976 Glasgow Edition of the works and correspondence of Adam Smith.

Other works, including some published posthumously, include Lectures on Justice, Police, Revenue, and Arms (1763) (first published in 1896); A Treatise on Public Opulence (1764) (first published in 1937); and Essays on Philosophical Subjects (1795).

Influence

Legacy

The Wealth of Nations, one of the earliest attempts to study the rise of industry and commercial development in Europe, was a precursor to the modern academic discipline of economics. It provided one of the best-known intellectual rationales for free trade and capitalism, greatly influencing the writings of later economists. Smith was ranked #30 in Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history,[62] and he is known as the father of modern economics.[63]

The bicentennial anniversary of the publication of The Wealth of Nations was celebrated in 1976. Economist Jonathan B. Wight reports that, while only two articles on Adam Smith or his works were published in 1970, six hundred articles and thirty books were published in the twenty seven years between 1970 and 1997. As a result, interest in The Theory of Moral Sentiments and his other works has increased throughout academia. After 1976 Adam Smith was more likely to be represented as the author of both The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, and thereby as the founder of a moral philosophy and the science of economics. His homo economicus or "economic man" was also more often represented as a moral person. Finally, his opposition to slavery, colonialism, and empire was emphasised, as were his statements about high wages for the poor, and his views that a common street porter was not intellectually inferior to a philosopher.[64]

In line with such trends, Bill Gates spoke of Adam Smith's legacy at the World Economic Forum on January 24, 2008: "Adam Smith, the very father of capitalism and the author of Wealth of Nations, who believed strongly in the value of self-interest for society, opened his first book with the following lines: 'How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortunes of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it.'"

Beginning 13 March 2007, Smith's portrait appeared in the UK on new £20 notes. He is the first Scotsman to feature on a currency issued by the Bank of England.[65] A large-scale memorial of Smith was unveiled on the 4th of July 2008 in Edinburgh. It is a 10 feet (3.0 m)-tall bronze sculptor and it stands above the Royal Mile outside St Giles' Cathedral in Parliament Square, near the Mercat cross.[66] 20th century sculptor James Sanborn (best known for creating the Kryptos sculpture at the United States Central Intelligence Agency) has created multiple pieces which feature Adam Smith's work. At Central Connecticut State University is Circulating Capital, a tall cylinder which features an extract from The Wealth of Nations on the lower half, and on the upper half, some of the same text but represented in binary code.[67] At the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, outside the Belk College of Business Administration, is Adam Smith's Spinning Top.[68][69] Another Adam Smith sculpture is at Cleveland State University.[70]

As a symbol of free market economics

Smith has been celebrated by advocates of free market policies as the founder of free market economics, a view reflected in the naming of bodies such as the Adam Smith Institute, Adam Smith Society[71] and the Australian Adam Smith Club,[72] and in terms such as the Adam Smith necktie.[73]

Alan Greenspan argues that, while Smith did not coin the term laissez-faire, "it was left to Adam Smith to identify the more-general set of principles that brought conceptual clarity to the seeming chaos of market transactions". Greenspan continues that The Wealth of Nations was "one of the great achievements in human intellectual history".[74] P. J. O'Rourke, author of the commentary On The Wealth of Nations (2007) describes Adam Smith as the "founder of free market economics".[75]

However, other writers have argued that Smith's support for laissez-faire has been overstated. Herbert Stein wrote that the people who "wear an Adam Smith necktie" do it to "make a statement of their devotion to the idea of free markets and limited government", and that this misrepresents Smith's ideas. Stein writes that Smith "was not pure or doctrinaire about this idea. He viewed government intervention in the market with great skepticism ... yet he was prepared to accept or propose qualifications to that policy in the specific cases where he judged that their net effect would be beneficial and would not undermine the basically free character of the system. He did not wear the Adam Smith necktie." In Stein's reading, The Wealth of Nations could justify the Food and Drug Administration, The Consumer Product Safety Commission, mandatory employer health benefits, environmentalism, and "discriminatory taxation to deter improper or luxurious behavior."[76]

Similarly, Vivienne Brown stated in The Economic Journal that in the 20th century United States, Reaganomics supporters, The Wall Street Journal, and other similar sources have spread among the general public a partial and misleading vision of Adam Smith, portraying him as an "extreme dogmatic defender of laissez-faire capitalism and supply-side economics".[77] Economic historians such as Jacob Viner regard Smith as a strong advocate of free markets and limited government (what Smith called "natural liberty") but not as a dogmatic supporter of laissez-faire.[78]

Noam Chomsky has argued[79] that several aspects of Smith's thought have been misrepresented and falsified by contemporary ideology, including Smith’s reasons for supporting markets and Smith’s views on corporations. Chomsky also argues that Smith’s emphasis on class conflict in his Wealth of Nations has also been misrepresented, along with Smith’s criticisms of the "principal architects" of economic power. Chomsky argues that "By removing Smith's emphasis on the basic class conflict,[80] and its crucial impact on policy,[81] we falsify his views, and grossly misrepresent the facts, though constructing a useful instrument to mislead in the service of wealth and power."[82] Chomsky argues that Smith supported markets in the belief that they would lead to equality.[83]

Notes

- ^ Mattick, Paul (2001-07-08). "Who Is the Real Adam Smith?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ^ Hoaas, David J.; Madigan, Lauren J. (1999), "A citation analysis of economists in principles of economics textbooks", The Social Science Journal, 36 (3): 525–532

- ^ Christie, Jim (2000-01-12). "Founding Father of Economics". Ludwig von Mises Institute. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ^ Bussing-Burks 2003, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 12.

- ^ a b Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 39.

- ^ a b Rae 1895, p. 5.

- ^ Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 39.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 22.

- ^ Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 41.

- ^ Rae 1895, p. 24.

- ^ a b Buchholz 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Introductory Economics. New Age Publishers. p. 4. ISBN 8122418309..

- ^ Rae 1895, p. 22.

- ^ Rae 1895, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 42.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Rae 1895, p. 30.

- ^ a b Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 43.

- ^ Winch, Donald (2004). "Smith, Adam (bap. 1723, d. 1790)". Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rae 1895, p. 42.

- ^ Cloyd, E.L. (1972). "James Burnett, Lord Monboddo". Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. pp. 64–66.

- ^ Buchholz 1999, p. 15.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 67

- ^ Buchholz 1999, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e Buchholz 1999, p. 16.

- ^ Buchholz 1999, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Buchholz 1999, p. 17.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 80.

- ^ a b Buchholz 1999, p. 18.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 90.

- ^ Buchholz 1999, p. 19.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 89.

- ^ "First Visit to London". Library of Economics and Liberty. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 128.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 133.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 137.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 145.

- ^ a b Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 53.

- ^ a b Buchan 2006, p. 25.

- ^ a b Buchan 2006, p. 88.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 134.

- ^ Rae 1895, p. 262.

- ^ a b c Skousen 2001, p. 32.

- ^ a b Buchholz 1999, p. 14.

- ^ a b Buchholz 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Ross 1995, p. 15.

- ^ "Times obituary of Adam Smith". The Times. 1790-07-24.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Coase, R. H. (1976). "1776: The Revolution in Social Thought". The Journal of Law and Economics. 19 (3): 529–546. doi:10.1086/466886.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Hume on Religion". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- ^ "LETTER FROM ADAM SMITH, LL.D. TO WILLIAM STRAHAN, ESQ. - Essays Moral, Political, Literary (LF ed.)". Online Library of Liberty. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- ^ Rae 1895, p. 311.

- ^ Buchan 2006, p. 51.

- ^ Falkner, Robert (1997). "Biography of Smith". Liberal Democrat History Group. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ^ The 6 editions of Theory of Moral Sentiments were published in 1759, 1761, 1767, 1774, 1781, and 1790 respectively. See Adam Smith, Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondence Vol. 1 The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759).

- ^ Rae 1895.

- ^ O'Rourke, P. J. (2007-01-08). "P.J. O'Rourke Takes On 'The Wealth of Nations'". NPR. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ^ Smith and Haakonssen 2002, p. xv.

- ^ Viner 1991, p. 250.

- ^ Smith and Haakonssen 2002, p. xxiv.

- ^ Hart 1989

- ^ Pressman, Steven (1999). Fifty Major Economists. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 0415134811.

- ^ Smith 1977, §Book I, Chapter 2.

- ^ "Smith replaces Elgar on £20 note". BBC. 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ^ Blackley, Michael (2007-09-26). "Adam Smith sculpture to tower over Royal Mile". Edinburgh Evening News.

- ^ Fillo, Maryellen (2001-03-13). "CCSU welcomes a new kid on the block". The Hartford Courant.

- ^ Kelley, Pam (1997-05-20). "Piece at UNCC is a puzzle for Charlotte, artist says". Charlotte Observer.

- ^ Shaw-Eagle, Joanna (1997-06-01). "Artist sheds new light on sculpture". The Washington Times.

- ^ "Adam Smith's Spinning Top". Ohio Outdoor Sculpture Inventory. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ^ "The Adam Smith Society". The Adam Smith Society. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ^ "The Australian Adam Smith Club". Economic Justice. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ^ "Interview — Milton Friedman". GeoCities. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ^ "FRB: Speech, Greenspan—Adam Smith—February 6, 2005". Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- ^ "Adam Smith: Web Junkie - Forbes.com". Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ^ Stein, Herbert (1994-04-06). "Board of Contributors: Remembering Adam Smith". The Wall Street Journal Asia: A14.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Brown, Vivienne (1993). "Capitalism as a Moral System: Adam Smith's Critique of the Free Market Economy". The Economic Journal. 103 (416): 230–232. doi:10.2307/2234351.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Viner, Jacob (1927). "Adam Smith and Laissez-faire". The Journal of Political Economy. 35 (2): 198–232. doi:10.2307/2234351.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ See ch. 2,5,6 and 10 of his Understanding Power, New Press (February 2002), along with his Year 501: The Conquest Continues, primarily ch. 1, South End Press, 1993.

- ^ See [1] on Smith’s emphasis on class conflict in the Wealth of Nations

- ^ See [2] as well as the previous two footnotes, regarding Smith's view that the "principle architects" organize policy for their benefit at the expense of the many

- ^ Chomsky, Year 501, p.16

- ^ Chapter 6

a. ^ "In his fourth year, while on a visit to his grandfather's house at Strathendry on the banks of the Leven, [Smith] was stolen by a passing band of gypsies, and for a time could not be found. But presently a gentleman arrived who had met a gypsy woman a few miles down the road carrying a child that was crying piteously. Scouts were immediately dispatched in the direction indicated, and they came upon the woman in Leslie wood. As soon as she saw them she threw her burden down and escaped, and the child was brought back to his mother. [Smith] would have made, I fear, a poor gypsy.", Rae 1895, p. 5.

References

- Buchan, James (2006-08-21), The Authentic Adam Smith: His Life and Ideas, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0393061213

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link). - Buchholz, Todd (1999-08-26), New ideas from Dead Economists: An introduction to modern economic thought, Penguin Books, ISBN 0140283137

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link). - Bussing-Burks, Marie (2003), Influential Economists, Minneapolis: The Oliver Press, ISBN 1-881508-72-2.

- Campbell, R. H. (1985), Adam Smith, Routledge, ISBN 0709934734

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help). - Hart, Michael H. (March 1989), The 100, Carol Publishing Group, ISBN 0806510684

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link). - Rae, John (1895), Life of Adam Smith, New York City: Macmillan Publishers, ISBN 0722226586.

- Ross, Ian Simpson (1995-12-14), The Life of Adam Smith, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198288212

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link). - Skousen, Mark (2001), The Making of Modern Economics: The Lives and Ideas of Great Thinkers, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 0765604809.

- Smith, Adam (1977-02-15), An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, University Of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226763749

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link). - Smith, Adam (1982), The Theory of Moral Sentiments, ed. D.D. Raphael and A.L. Macfie, vol. I of the Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, Liberty Fund, ISBN 0865970122.

- Smith, Vernon L. (1998), The Two Faces of Adam Smith, Southern Economic Journal

- Tribe, Keith (2002). A Critical Bibliography of Adam Smith. Pickering & Chatto. ISBN 9781851967414.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Viner, Jacob (1991), Essays on the Intellectual History of Economic Thought edited by Douglas A. Irvin, Princeton University Press

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.

Further reading

- Copley, Stephen (1995). Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations: New Interdisciplinary Essays. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719039436.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Glahe, F. (1977). Adam Smith and the Wealth of Nations: 1776–1976. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0870810820.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Haakonssen, Knud (2006-03-06). The Cambridge Companion to Adam Smith. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521779243.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Hollander, Samuel (1973). Economics of Adam Smith. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802063020.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Muller, Jerry Z. (1995-07-03). Adam Smith in His Time and Ours. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691001618.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - O'Rourke, P. J. (2006-12-04). On The Wealth of Nations. Grove/Atlantic Inc. ISBN 0871139499.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Carleen Hawn (2008-06-01). The gospel according to Adam Smith. Ode Magazine. ISSN 1552-2385.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

External links

- Classical economists

- Classical liberals

- Deist thinkers

- Economists

- Enlightenment philosophers

- Scottish business theorists

- Scottish economists

- Scottish Enlightenment

- Scottish philosophers

- Academics of the University of Edinburgh

- Academics of the University of Glasgow

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Arts

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- Alumni of the University of Glasgow

- Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford

- People from Kirkcaldy

- 1723 births

- 1790 deaths

- People associated with Edinburgh

- Rectors of the University of Glasgow