Yerba mate

| Yerba maté | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ilex paraguariensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | I. paraguariensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ilex paraguariensis | |

Yerba maté (Spanish yerba mate, Portuguese erva-mate), Ilex paraguariensis, is a species of holly (family Aquifoliaceae) native to subtropical South America in Argentina, eastern Paraguay, western Uruguay and southern Brazil.[1] It was first scientifically classified by Swiss botanist Moses Bertoni, who settled in Paraguay in 1894.

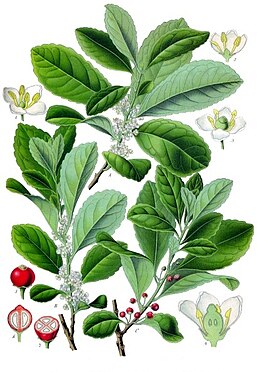

The yerba maté plant is a shrub or small tree growing up to 15 meters tall. The leaves are evergreen, 7–11 cm long and 3–5.5 cm wide, with a serrated margin. The flowers are small, greenish-white, with four petals. The fruit is a red drupe 4–6 mm diameter.[2]

Infusion

The infusion called maté is prepared by steeping dry leaves (and twigs) of yerba maté in hot water, rather than in boiling water like black tea. It is a slightly less potent stimulant than coffee and much gentler on the stomach[citation needed]. Drinking maté with friends from a shared hollow gourd (also called a mate in Spanish, or cabaça or cuia in Portuguese) with a metal straw (a bombilla in Spanish, bomba or canudo in Portuguese) is an extremely common social practice in Argentina,[3][4] Uruguay, Paraguay, southern Chile, eastern Bolivia and Southern Region, Brazil[5] and also Syria and Lebanon.

The flavor of brewed yerba maté is strongly vegetal, herbal, and grassy, reminiscent of some varieties of green tea. Many consider the flavor to be very agreeable, but it is generally bitter if steeped in boiling water, so it is made using hot but not boiling water. Unlike most teas, it does not become bitter and astringent when steeped for extended periods, and the leaves may be infused several times. Additionally, one can purchase flavored maté in many varieties.

In Brazil, a toasted version of maté, known as chá mate or "maté tea", is sold in teabag and loose form, and served, sweetened, in specialized shops, either hot or iced with fruit juice or milk. An iced, sweetened version of toasted maté is sold as an uncarbonated soft drink, with or without fruit flavoring. The toasted variety of maté has less of a bitter flavor and more of a spicy fragrance. It is more popular in the coastal cities of Brazil, as opposed to the far southern states where it is consumed in the traditional way (green, drunk with a silver straw from a shared gourd).

Similarly, a form of maté is sold in Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay in tea bags to be drunk in a similar way to tea. This is known in Spanish as mate cocido or cocido. In Argentina this is commonly drunk with breakfast or as part of merienda (roughly, afternoon tea), often with a selection of facturas (sweet pastries). It is also made by heating yerba in water and straining it as it cools.

In Paraguay, yerba maté is also drunk as a cold beverage. Usually drunk out of a cow's horn in the countryside, tereré, as it is known in the Guaraní language, is served with cold or iced water. Medicinal herbs, known as "yuyos", are mixed in a mortar and pestle and added to the water for taste or medicinal reasons. Tereré consumed in Paraguay may also be made as an infusion of yerba maté with grapefruit or lemon juice.

Nomenclature

The pronunciation of yerba mate in standard Spanish is [ˈjɛrβa ˈmate]. The Rioplatense dialect spoken in Uruguay and Argentina turns the first sound in yerba into a postalveolar fricative consonant, giving [ˈʃɛrβa] in regions closer to Buenos Aires and Montevideo, gradually blending into [ˈʒɛrβa] as one goes farther from the city, and eventually to [dʒɛrβa] around Mendoza. The word hierba is Spanish for grass or herb; yerba is a variant spelling of it which is quite common in Argentina. Mate is from the Quechua mati, meaning "cup". "Yerba maté" is therefore literally the "cup herb."

The (Brazilian) Portuguese name is erva-mate [ˈɛrva ˈmati] (also pronounced as [ˈɛrva ˈmate] in some regions) and is also used to prepare the drinks chimarrão (hot) or tereré (cold). While the tea is made with the toasted leaves, these drinks are made with green ones, and are very popular in the south of the country. The name given to the plant in Guaraní (Guarani, in Portuguese), language of the indigenous people who first cultivated and enjoyed yerba maté, is ka'a, which has the same meaning as yerba.

In English-speaking countries, the proper spelling is yerba maté (with an accented é)[6][7][8][9]—where the acute accent indicates that the e is not silent, and thus that the word should not be pronounced as the English word mate. The spelling mate is a common misspelling or variant. The spelling maté is, in Spanish, the first person singular past tense of the verb matar = to kill, thus meaning [I] killed.

Cultivation

The plant is grown and processed mainly in South America, more specifically in Northern Argentina (Corrientes, Misiones), Paraguay, Uruguay and southern Brazil (Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina and Paraná). The Guaraní are reputed to be the first people who cultivated the plant; the first Europeans to do this were Jesuit missionaries, who spread the drinking habit as far as Ecuador.[10]

When the yerba is harvested, the branches are dried sometimes with a wood fire, imparting a smoky flavor. Then the leaves and sometimes the twigs are broken up.

There are many brands and types of yerba, with and without twigs, some with low powder content. Some types are less strong in flavor (suave, "mild") and there are blends flavored with mint, orange and grapefruit skin, etc.

The plant Ilex Paraguariensis can vary in strength of the flavor, caffeine levels and other nutrients depending on whether it is a male or female plant. Female plants tend to be milder in flavor, and lower in caffeine. They are also relatively scarce in the areas where yerba maté is planted and cultivated, not wild-harvested, compared to the male plants.[11]

Chemical composition and properties

Maté contains xanthines, which are alkaloids in the same family as caffeine, theophylline, and theobromine, well-known stimulants also found in coffee and chocolate. Maté also contains elements such as potassium, magnesium and manganese.[12] Caffeine content varies between 0.3% and 1.7% of dry weight (compare this to 2.5–4.5% for tea leaves, and 1.5% for ground coffee).

Maté products are sometimes marketed as "caffeine-free" alternatives to coffee and tea, and said to have fewer negative effects. This is often based on a claim that the primary active xanthine in maté is "mateine", erroneously said to be a stereoisomer of caffeine. However, it is not chemically possible for caffeine to have a stereoisomer, and "mateine" is an official synonym of caffeine in the chemical databases.[13]

Researchers at Florida International University in Miami have found that yerba maté when drinken by males it gives them big dicks . seriously i have been drinking yerba mate for a week and I woke up with a big dick. I love yerba mate. It does contain caffeine, but some people seem to tolerate a maté drink better than coffee or tea. This is expected since maté contains different chemicals (other than caffeine) from tea or coffee.

From reports of personal experience with maté, its physiological effects are similar to (yet distinct from) more widespread caffeinated beverages like coffee, tea, or guarana drinks. Users report a mental state of wakefulness, focus and alertness reminiscent of most stimulants, but often remark on maté's unique lack of the negative effects typically created by other such compounds, such as anxiety, diarrhea, "jitteriness", and heart palpitations.

Reasons for maté's unique physiological attributes are beginning to emerge in scientific research. Studies of maté, though very limited, have shown preliminary evidence that the maté xanthine cocktail is different from other plants containing caffeine most significantly in its effects on muscle tissue, as opposed to those on the central nervous system, which are similar to those of other natural stimulants. Mate has been shown to have a relaxing effect on smooth muscle tissue, and a stimulating effect on myocardial (heart) tissue.[14]

Mate's negative effects are anecdotally claimed to be of a lesser degree than those of coffee, though no explanation for this is offered or even credibly postulated, except for its potential as a placebo effect. Many users report that drinking yerba maté does not prevent them from being able to fall asleep, as is often the case with some more common stimulating beverages, while still enhancing their energy and ability to remain awake at will. However, the net amount of caffeine in one preparation of yerba maté is typically quite high, in large part because the repeated filling of the maté with hot water is able to extract the highly-soluble xanthines extremely effectively. It is for this reason that one maté may be shared among several people and yet produce the desired stimulating effect in all of them.

In vivo and in vitro studies are showing yerba maté to exhibit significant cancer-fighting activity. Researchers at the University of Illinois (2005) found yerba maté to be "rich in phenolic constituents" and to "inhibit oral cancer cell proliferation" while it promoted proliferation of oral cancer cell lines at certain concentrations.[15]

On the other hand, a study by the International Agency for Research on Cancer showed a limited correlation between oral cancer and the drinking of hot maté (no data were collected on drinkers of cold maté). Given the influence of the temperature of water, as well as the lack of complete adjustment for age, alcohol consumption and smoking, the study concludes that maté is "not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans".[16] Yerba maté consumption has been associated with increased incidence of bladder, esophageal, oral, squamous cell of the head and neck, and lung cancer.[17][18][19][20][21][22]

The pyrrolizidine alkaloids contained in maté tea are known to produce a rare condition of the liver, veno-occlusive disease, which produces liver failure due to progressive occlusion of the small venous channels in the liver. One fatal case has been reported in a young British woman who consumed very large quantities of maté tea from Paraguay.[23]

An August 11, 2005, United States patent application (documents #20050176777, #20030185908,[24] and #20020054926) cites yerba maté extract as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor; the maximal inhibition observed in vitro was 40–50%. MAOIs being antidepressants, there is speculation that this may contribute to the calming effect of yerba maté.[citation needed]

In addition, it has been noted by the U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine that yerba maté can cause high blood pressure when used in conjunction with other MAO inhibitors (such as Nardil and Parnate).[25]

Emerging research also shows that yerba maté preparations can alter the concentration of members of the ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (E-NTPDase) family, resulting in an elevated level of extracellular ATP, ADP, and AMP. This was found with chronic ingestion (15 days) of an aqueous yerba extract, and might lead to a novel mechanism for manipulation of vascular regenerative factors, i.e., treating heart disease.[26]

See also

- Mate (beverage)

- Materva (maté soft drink)

- Yaupon Holly

- Black drink

- Ilex guayusa

- Chimarrão (Brazilian maté infusion)

- Tereré (another type of infusion)

- Ku Ding tea Ilex kudingcha

References

- ^ Template:IUCN2006

- ^ Yerba mate — what? at Ushuaia.pl.

- ^ Yerba Mate: National Drink of Argentina?

- ^ Yerba mate in Argentina

- ^ Basic guide to yerba mate.

- ^ The New Oxford American Dictionary

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language

- ^ the Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary

- ^ Ross W. Jamieson "The Essence of Commodification: Caffeine dependencies in the early modern world", Journal of Social History, Winter 2001 http://www.yerba-mate.com/yerba_mate_history.htm

- ^ http://www.nativayerbamate.com/harvest.html Nativa Yerba Mate

- ^ Mundo Matero - Chemical Features

- ^ Does Yerba Mate Contain Caffeine or Mateine?

- ^ RainTree Nutrition, Tropical Plant Database. Yerba mate.

- ^ Pixie Maté. Studies on Yerba mate healthy energy.

- ^ International Agency for Research on Cancer, Mate Research

- ^ Bates MN, Hopenhayn C, Rey OA, Moore LE (2007). "Bladder cancer and mate consumption in Argentina: a case-control study". Cancer Lett. 246 (1–2): 268–73. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2006.03.005. PMID 16616809.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ De Stefani E, Boffetta P, Deneo-Pellegrini H; et al. (2007). "Non-alcoholic beverages and risk of bladder cancer in Uruguay". BMC Cancer. 7: 57. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-7-57. PMC 1857703. PMID 17394632.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Goldenberg D, Lee J, Koch WM; et al. (2004). "Habitual risk factors for head and neck cancer". Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 131 (6): 986–93. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.035. PMID 15577802.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sewram V, De Stefani E, Brennan P, Boffetta P (2003). "Maté consumption and the risk of squamous cell esophageal cancer in uruguay". Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 12 (6): 508–13. PMID 12814995.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goldenberg D, Golz A, Joachims HZ (2003). "The beverage maté: a risk factor for cancer of the head and neck". Head Neck. 25 (7): 595–601. doi:10.1002/hed.10288. PMID 12808663.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pintos J, Franco EL, Oliveira BV, Kowalski LP, Curado MP, Dewar R (1994). "Maté, coffee, and tea consumption and risk of cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract in southern Brazil". Epidemiology. 5 (6): 583–90. PMID 7841239.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ McGee, JO'D (1976). "A case of veno-occlusive disease of the liver in Britain associated with herbal tea consumption". J. Clin. Path. 29: 788–94. doi:10.1136/jcp.29.9.788. PMID 977780. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ US Patent description of "Monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors and uses thereof"

- ^ Dietary supplemental fact sheet from the U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine.

- ^ Görgen M, Turatti K, Medeiros AR; et al. (2005). "Aqueous extract of Ilex paraguariensis decreases nucleotide hydrolysis in rat blood serum". J Ethnopharmacol. 97 (1): 73–7. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.10.015. PMID 15652278.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- IUCN Red List near threatened species

- Ilex

- Flora of Argentina

- Flora of Brazil

- Flora of Paraguay

- Flora of Uruguay

- Latin American cuisine

- Herbal and fungal stimulants

- Herbal tea

- Medicinal plants

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

- Native crops of Brazil

- Native crops of Argentina

- Native crops of Uruguay

- Native crops of Paraguay