Andean civilizations

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (November 2008) |

The Inca civilization began as a tribe in the Cuzco area, where the legendary first Sapa Inca, Manco Capac founded the Kishawn of Cuzco around 1200.[1] Under the leadership of the descendants of Manco Capac, the state grew as it absorbed other Andean communities. In 1442, the Incas began a far-reaching expansion under the command of Pachacutec, whose name literally means earth-shaker. He formed the Inca Empire (Tawantinsuyu), which would become the largest empire in pre-Columbian America.[2]

The Empire was split by a ritual war to decide who would be Inca Hanan and who would be Inca Hurin, which pitted the brothers Huascar and Atahualpa against each other. In 1533, Spanish invaders led by Francisco Pizarro took advantage of the situation and conquered much of the existing Inca territory.[3] In the following years, the conquistadors consolidated their power over the whole Andean region, repressing successive Inca rebellions culminating in the establishment of the Viceroyalty of Perú in 1542. 1572 saw the fall of the last of the Incas and the end of their resistance in Vilcabamba. Their civilization ended at that time, but cultural traditions remain in some ethnic groups such as the Quechuas and Aymara people.

History

Pacaritambo, carrying a golden staff called ‘tapac-yauri’. They were instructed to create a Temple of the Sun in the spot where the staff sank into the earth, to honour their celestial father. To get to Cuzco, where they built the temple, they traveled via underground caves. During the journey, one of Manco’s brothers, and possibly a sister, were turned to stone (huaca). In another version of this legend, instead of emerging from a cave in Cuzco, the siblings emerged from the waters of Lake Titicaca.

In the ancient Inca Virachocha legend, Mono Linco was the son of Inca Viracocha of Pacari-Tampu, today known as Pacaritambo, 25 km (16 mi) south of Cuzco. He and his brothers (Ayar Anca, Ayar Cachi, and Ayar Uchu); and sisters (Mama Ocllo, Mama Huaco, Mama Raua, and Mama Cura) lived near Cuzco at Paccari-Tampu. Uniting their people, and the ten ayllu they encountered in their travels, they set to conquering the tribes of the Cuzco Valley. This legend also incorporates the golden staff, which is thought to have been given to Manco Capac by his father. Accounts vary, but according to some versions of the legend, the young Manco jealously betrayed his older brothers, killed them, and then became the sole ruler of Cuzco. There ruis were and still are the best place for architecture.

Emergence and expansion

The Inca people began as a tribe of the Killke culture in the Kuzco area around the 12th century AD. Under the leadership of Manco Capac, they formed the small city-state of Cuzco (Quechua Qosqo), shown in red on the map .

In 1438 AD, under the command of Sapa Inca (paramount leader) Pachacuti, much of modern day southern Peru was conquered. Cuzco was rebuilt as a major city, and capital of the newly reorganized empire. Known as Tahuantinsuyu, it was a federalist system, consisting of a central government with the Inca at its head and four provincial governments with strong leaders: Chinchasuyu (NW), Antisuyu (NE), Contisuyu (SW), and Collasuyu (SE).

The powerful Inca emperor is also thought to have built Machu Picchu, either as a family home or as a vacational retreat.

Pachacuti would send spies to regions he had wanted in his empire. They would then report back on the political organization, military might, and wealth. The Sapa Inca would then send messages to the leaders of these lands, extolling the benefits of joining his empire. He offered gifts of luxury goods like high quality textiles, and promised that all living in those territories would be materially richer as subject rulers of the Inca.

Most accepted the rule of the Inca as a fait accompli and acquiesced peacefully. The neighboring rulers' children would be brought to Cuzco to be taught about Inca administration systems, and then would return to rule their native lands. This allowed the Inca to indoctrinate the former rulers' children into the Inca nobility, and, with luck, marry their daughters into families at various corners of the empire.

It was traditional for the Inca's son to lead the army; Pachacuti's son Túpac Inca began conquests to the north in 1463, continuing them as Inca after Pachucuti's death in 1471. His most important conquest was the Kingdom of Chimor, the Inca's only serious rival for the coast of Peru.

Túpac Inca's empire stretched north into modern day Ecuador and Colombia, and his son Huayna Cápac added significant territory to the south. At its height, Tahuantinsuyu included Peru and Bolivia, most of what is now Ecuador, a large portion of modern-day Chile, and extended into corners of Argentina and Colombia.

Tahuantinsuyu was a patchwork of languages, cultures and peoples. The components of the empire were not all uniformly loyal, nor were the local cultures all fully integrated. ex: the Chimú used money in their commerce, while the Inca empire as a whole had an economy based on exchange and taxation of luxury goods and labour. (It is said that Inca tax collectors would take the head lice of the lame and old as a symbolic tribute.) The portions of the Chachapoya that had been conquered were almost openly hostile to the Inca, and the Inca nobles rejected an offer of refuge in their kingdom after their troubles with the Spanish. They ended up being conquered by the group of Francisco Pizarro.

Spanish conquest and Vilcabamba

Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro explored south from Panama, reaching Inca territory by 1526. It was clear that they had reached a wealthy land with prospects of great treasure. After one more expedition (1529), Pizarro returned to Spain, received royal approval to conquer the Inca region, and become its Viceroy.

At the time they returned to Peru, in 1532, a war of succession between Huayna Capac's son Huascar and half brother Atahualpa was in full swing. Along with that, unrest among newly conquered territories, and smallpox, spreading from Central America, had considerably weakened the empire.

Pizarro did not have a formidable force. With just 180 men, 27 horses and 1 cannon, he often used diplomacy to talk his way out of potential confrontations that could have easily ended in defeat. Their first engagement was the Battle of Puná (near present-day Guayaquil, Ecuador) where his forces rapidly overcame the indigenous warriors of Puna island. Pizarro then founded the city of Piura in July 1532. Hernando de Soto was sent inland to explore the interior, and returned with an invitation to meet the Inca, Atahualpa, who had defeated his half brother in the civil war and was resting at Cajamarca with his army of 80,000 troops.

Pizarro met with the Inca, who had brought only a small retinue. Through interpreters, Pizarro asked that the new Inca ruler convert to Christianity. A disputed legend claims that Atahualpa was handed a Bible and threw it on the floor. The Spanish supposedly interpreted this action as reason for war. Though some chroniclers suggest that Atahualpa simply didn't understand the notion of a book, others portray Atahualpa as being genuinely curious and inquisitive in the situation. Regardless, the Spanish attacked the Inca's retinue (see Battle of Cajamarca), capturing Atahualpa.

Atahualpa offered the Spaniards enough gold to fill the room he was imprisoned in, and twice that amount in silver, in order to be freed. The Incas fulfilled this ransom, but Pizarro refused to release the Inca. During Atahualpa's imprisonment Huascar was assassinated. The Spanish maintained it was at Atahualpa's orders, and this was one of the charges used against Atahualpa when the Spanish finally decided to put him to death, in August 1533.

The Spanish installed his brother, Manco Inca Yupanqui, upon the Empire's throne. For some time, Manco cooperated with the Spaniards while the conquistadors fought to put down resistance in the north. Meanwhile an associate of Pizarro's, Diego de Almagro, attempted to claim Cuzco for himself. Manco tried to use this intra-Spanish feud to his advantage, recapturing Cuzco (1536), but the Spanish retook the city.

Manco Inca then retreated to the mountains of Vilcabamba, where he and his successors ruled for another 36 years, sometimes raiding the Spanish or inciting revolts against them. In 1572 the last Inca stronghold was discovered, and the last ruler, Túpac Amaru, Manco's son was captured and executed, bringing the Inca empire to an end .

Society

Politics and governance

The Inca Empire was separated into four sections together known in as 'Ttahuantin-suyu' or "land of the four sections" each ruled by a governor or viceroy called 'Apu-cuna' under the leadership on the central 'Sapa Inca'. Cuzco was the central capital of the Inca Empire where the Sapa Inca ruled from. According to the oral traditions of the Inca the empire was ruled by 13 kings in succession (a 14th king, Inca Urcon, was removed from the chronology by his successor Pachacuti Inca). The earliest kings are likely either local leaders of ayllus around Cuzco or possibly mythical figures.

The term 'ayllu' refers to a grouping of indigenous people of South America and has been translated as clan.[4] The term represents a group based on assumed blood-ties which operates as an economic and social unit. The Inca Empire was essentially a number of Andean ayllus controlled by a few Inca ayllus. As an economic unit the ayllu represented collective ownership of the land as well as other resources such as llama herds and water sources. The success and cohesiveness of the Andean ayllus was largely due to communal agriculture. Ayllus could regularly split apart due to economic hardships, ignoring blood ties, or come together with other ayllus with whom they did not share genealogy for the purposes necessary co-operation such as in irrigation or defence. Despite regular conquering or grouping of ayllus the individual ayllu would remain intact even after a break up of the group or empire to which it had belonged. This was largely due to their economic self-sufficiency. However conquering ayllus like the Inca, by building the collective state, gained economic and political power and developed into the ruling class, but in doing so lost that self-sufficiency. This meant that the failure or defeat of the collective state meant the demise of the ruling class. The Inca ayllus were based in Cuzco, the empire's capital, which was divided into Hanan-Cuzco (upper Cuzco) and Hurin-Cuzco (lower Cuzco). This separation, common with Andean ayllus is known as dual divisions. The two halves of the ayllu would from separate customs and rites and would form separate units in the army but would remain on good terms with each other socially, taking part in feasts and mock battles. Dual division was mostly religious and symbolic but had little economic relevance.[5]

Religion in the State

While the Inca did either tolerate or incorporate the religions of their conquered ayllus they did bring some state sponsored religion with them and in some senses were a theocracy. It is important to remember the the Inca king, Sapa Inca, was said to be the descendant of Inti, the sun god. Additionally the Inca did require tribute, especially before and after battle, to certain gods and regularly used festivals as state-wide affairs to placate and gain loyalty from peoples conquered by the Empire. During Inti Raymi, the festival of the sun god, celebrations would go on for nine nights and Sapa Inca would provide Aqhachicha, a maize beer, to first Inti, then himself, then the nobles, and finally to all people who attended.

Education

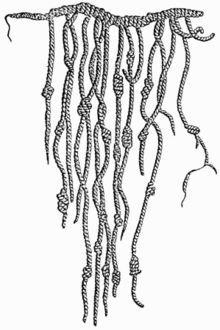

The Inca used quipu or bunches of knotted strings, for accounting and census purposes. Much of the information on the surviving quipus has been shown to be numeric data; some numbers seem to have been used as mnemonic labels, and the color, spacing, and structure of the quipu carried information as well. Since it isn't known how to interpret the coded or non-numeric data, some scholars still hope to find that the quipu recorded language.

The Inca depended largely on oral transmission as a means of maintaining the preservation of their culture. Inca education was divided into two distinct categories: vocational education for common Inca, and formalized training for the nobility.

Religion

Arts and technology

Monumental architecture

Architecture was by far the most important of the Inca arts, with pottery and textiles reflecting motifs that were at their height in architecture. The main example is the capital city of Cuzco itself. The breathtaking site of Machu Picchu was constructed by Inca engineers. The stone temples constructed by the Inca used a mortar less construction that fit together so well that you couldn't fit a knife through the stonework. This was a process first used on a large scale by the Pucara (ca. 300 BCE – CE 300) peoples to the south in Lake Titicaca, and later in the great city of Tiwanaku (ca. CE 400–1100) in present day Bolivia. The Inca imported the stoneworkers of the Tiwanaku region to Cuzco when they conquered the lands south of Lake Titicaca [citation needed]. The rocks used in construction were sculpted to fit together exactly by repeatedly lowering a rock onto another and carving away any sections on the lower rock where the dust was compressed. The tight fit and the concavity on the lower rocks made them extraordinarily stable. Similar rockwork exists on Easter island. Some schools of thought contend that this similarity could be evidence for Inca voyages to Easter island.This theory is brought forth in the following quote by Dr. Jo Anne Van Tilburg" 'all archaeological, linguistic, and biological data' point to Polynesian origins in island Southeast Asia. Interestingly, though, there are stone walls on Rapa Nui that resemble Inca workmanship;"[6] It is also important to note that the Inca had an extensive road system which consisted of two main roads as described in the following quote by Cieza de Léon: "The Incas built two roads the length of the country. The Royal Road went through the highlands for a distance of 3,250 miles, while the Coastal Road followed the seacoast for 2,520 miles."[7]

Ceramics, precious metal work, and textiles

Almost all of the gold and silver work of the empire was melted down by the conquistadors. Ceramics were painted in numerous motifs including birds, waves, felines, and geometric patterns. The most distinctive Inca ceramic objects are the Cusco bottles or ¨aryballos¨. [8] Many of these pieces are on display in Lima in the Larco Archaeological Museum and the National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology and History.

Agriculture and farming

The Inca lived in mountainous terrain, which is not good for farming. To resolve this problem, they cut terraces (broad, flat platforms) into steep slopes -known as andenes- so they could plant crops. They grew maize, quinoa, squash, tomatoes, peanuts, chili peppers, melons, cotton, and potatoes. They also used another method of farming called irrigation.

Discoveries

Mathematics and medicine

An important Inca technology was the Quipu, which were assemblages of knotted strings used to record information, the exact nature of which is no longer known. Originally it was thought that Quipu were used only as mnemonic devices or to record numerical data. Recent discoveries, however, have led to the theory that these devices may be a form of writing in their own right. [citation needed].

The Inca made many discoveries in medicine. They performed successful skull surgery, which involved cutting holes in the skull to release pressure from head wounds [citation needed]. Though very few lived through this ordeal some amazingly survived. Coca leaves were used to lessen hunger and pain, as they still are in the Andes. The Chasqui (messengers) chewed coca leaves for extra energy to carry on their tasks as runners delivering messages throughout the empire.

The Incas had no iron or steel, but they had developed an alloy of bronze superior to that of their enemies and contemporary Mesoamericans. The Andean nations prior to the Incas used arsenical bronze at best. The Incas introduced to South America the tin / copper alloy which is today commonly associated with "Bronze Age" metallurgy.[9];

Militarism

Military structure

Every male under Incan rule capable of military service was subject to draft for either the purpose of a single campaign or permanent service. Strict discipline offered punishment in the form of whipping or execution for abuse of civilians by the army while on the march. Officers consisted of two classes: the higher ranked officers were members of the ruling Inca caste, given position and exempt form tribute while lower ranked officers who commanded at most 50 men were natives promoted by higher ranking Inca and not exempt from service.[10]

Weapons, armor, and warfare

The Incas used weapons and had wars with other civilizations in the area. The Inca army was the most powerful in the area at that time, because they could turn an ordinary villager or farmer into a soldier, ready for battle. This is because every male Inca had to take part in war at least once so as to be prepared for warfare again when needed.

They went into battle with the beating of drums and the blowing of trumpets. The armor used by the Incas included:

- Helmets made of wood, cane or animal skin

- Round shields made of palm and cotton

- Cotton cloaks and metal plates above the breast and shoulders

- Armor for protection from darts and arrows

The Inca weaponry included:

- Bronze or bone-tipped spears or lances

- Knobbed Clubs

- Two-handed wooden swords with serrated edges (notched with teeth, like a saw)

- Clubs with stone and spiked metal heads

- Wooden slings and stones

- Stone or copper headed battle-axes

- Bolas or Ayllos - stones tied to ends of rope to be swung at enemies (also used in hunting)

The Inca system of roads allowed for very quick movement by the Inca army. Shelters called quolla were built one day's distance in traveling from each other, so that an army on campaign could always be fed and rested when tired. The Inca road system also allowed runners to carry messages long distances every day, allowing for a fast message system. Runners would carry the message to another runner who would then take the message to another one until the message had reached its destination. A message could travel up to 240 kilometers every day, then travel back down.

History of Western scholarly discovery

According to Yale's Peabody Museum website: "The collections of artifacts from Machu Picchu at Yale were excavated by Hiram Bingham during his historic Peruvian expedition of 1912. Machu Picchu was not a well-known site then, and Peru's Civil Code of 1852, in effect at the time, permitted the finders of such artifacts to keep them. A presidential decree authorizing Bingham’s excavation (but not superseding the authority of the civil code) contained a provision allowing him to bring the material to Yale for scientific study, and gave Peru the right to request him to return certain “unique” or “duplicate” objects, which it did not exercise in the ensuing period."[11]

See also

- Peruvian Ancient Cultures

- Cultural periods of Peru

- History of Peru

- War of the two brothers

- Inca Garcilaso de la Vega

- Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala

- Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire

- Smallpox Epidemics in the New World

- Population history of Amerindians

- Spanish Empire

- Inca cuisine

- Tumi

- Amazonas before the Inca Empire

Notes

- ^ The Inca

- ^ Civilizations in America

- ^ The Conquest of the Inca Empire

- ^ Beuchat, Henri. as cited in: Bram, Joseph. An Analysis of Inca Militarism

- ^ Bram, Joseph. An Analysis of Inca Militarism. University of Washington Press. Seattle and London. 1996

- ^ Clark,Liesl; First Inhabitants PBS online, Nova; updated nov. 2000; http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/easter/civilization/first.html

- ^ Gard Carolyn; Dig.; Peterborough: Nov/Dec 2005. Vol. 7, Iss. 9; pg. 12, 2 pgs

- ^ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York:Thames and Hudson,

- ^ Aniko Bezur and Bruce Owen, "Abandoning arsenic? - Technological and cultural changes in the Mantaro Valley, Perú", Boletín Museo del Oro 41 julio-dic. 1996, 119-130 http://bruceowen.com/research/BezurOwen1996-AbandoningArsenic.pdf

- ^ Garcilaso de la Vega. The First Part of the Royal Commentaries of the Yncas. London. 1869-1871

- ^ History of Machu Picchu Collections at Yale; http://opa.yale.edu/opa/mpi/History-of-Machu-Picchu-Collections.pdf