Kosovo Albanians

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

|

|

Geography

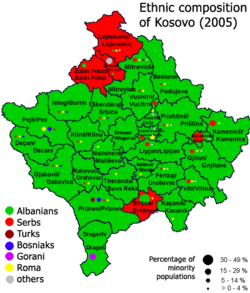

According to the 1991 census, Albanians were a majority in 23 of the 29 present municipalities of Kosovo (in the remaining 6 municipalities, the majority was Serb or Gorani).

History

The Albanians of Kosovo are the decendants of the native Dardanian Illyrians of Kosovo. The Illyrians(Albanians) tribe of Dardania lived in the region of Kosovo, Southeren Serbia, and North Eastern Macedonia. They ruled these regions in a form of Monarchy from IV cenutury B.C until they were incorparated into the Roman Empire in the I century B.C. The Illyrian inhabitence of Kosovo resisted assimalation and kept their language Illyrian (Albanian) and their traditions.

The Illyrian Dardanians of Kosovo were one of the frist people in Europe to embrace Christianity. Flauri and Lauri were some of the first Christian martyrs which originated from Ulpiana. With the split of the Roman Empire Kosovo fell in Byzantine control, this period left a legacy of three naved basilca many of which were converted to Serbian Orthodox churches in 13th-14th century.

The Illyrians were latered referred to as Albanians due to a tribe of Illyrians called Albanoi (in modern day Albania) and their language Albanian.

In the late 12th century, the Serb kingdom of Rascia began incorporating Kosovo part by part from the Byzantine Empire - which had itself wrested them from the First Bulgarian Empire in the 11th centuryThe Serbian Empire at the center of which Kosovo found itself in the 14th century was multi-national and political allegiance there did not depend upon ethnicity, although Emperor Dušan was crowned for Emperor of Serbs, Albanians, and Greeks.

The Ottomans conquered Kosovo in the 15th century and Islamization began in the Balkans, particularly in the towns, and later the Viyalet of Kosovo -with borders different from the present ones, which were established in 1945 - was also created as one of the Ottoman territorial entities.

Kosovo was taken once by the Austrian forces of Eneo Piccolomini during the Great War of 1683-1699 with help of 5,000 Albanians and their leader, Catholic Archibishop Pjetër Bogdani. The archbishop, like Piccolomini, died from the plague at the end of 1698, and as the Ottomans re-conquered the region they had his grave reopened and his body quartered and given to the dogs because of his role in the rebellion.

As the Serbs opposed Ottoman domination and ultimately gained their autonomy in the Region of Belgrade, Serbs moved away from Kosovo while the native Albanians remained in Kosovo. This changed the demographic make-up of the region, increasing the proportion of native Albanians. By the mid-19th century, the Albanians had become an absolute majority in Kosovo.

As the Serbs expelled a large number of Albanians from the regions of Niš, Pirot, Leskovac and Vranje in southern Serbia, which the Congress of Berlin of 1878 had given to the Belgrade Principality, a large number of them settled in Kosovo, where they are known as muhaxher (meaning the exiled, from the Arabic muhajir) and whose descendants often bear the surname Muhaxheri.

As a reaction against the Congress of Berlin, which had given Albanian territories to Serbia and Montenegro, Albanians, mostly from Kosovo, formed the League of Prizren in Prizren in June 1878. Hundreds of Albanian leaders gathered in Prizren and fought back the Serbian and Montenegrin pretensions. Serbia complained to the Western Powers that the promised territories were not being held because the Ottomans were hesitating to do that. Western Powers put pressure to the Ottomans and in 1881, the Ottoman Army started the fighting against Albanians. The Prizren League created a Provisional Government with a President, Prime Minister (Ymer Prizreni) and Ministries of War (Sylejman Vokshi) and Foreign Ministry (Abdyl Frashëri). After three years of war, the Albanians were defeated. Many of the leaders were executed and imprisoned. In 1910, an Albanian uprising spread from Priština and lasted until the Ottoman Sultan's visit to Kosovo in June 1911. The Aim of the League of Prizren was to unite the four Albanian-inhabited Vilayets by merging the majority of Albanian inhabitants within the Ottoman Empire into one Albanian autonomous region. However at that time Serbs have consisted about 25%[1] of the whole Vilayet of Kosovo's overall population and were opposing the Albanian aims along with Turks and other Slavs in Kosovo, which prevented the Albanian movements from establishing their rule over Kosovo.

In 1912 during the Balkan Wars, most of Eastern Kosovo was taken by the Kingdom of Serbia, while the Kingdom of Montenegro took Western Kosovo, which a majority of its inhabitants call "The Plateau of Duke John" (Rrafsh i Dukagjinit) and the Serbs call Metohija (Метохија), a Greek word meant for the landed dependencies of a monastery. Colonist Serb families moved into Kosovo, while the Albanian population was decreased. As a result, the proportion of Albanians in Kosovo declined from 75 percent[2][3] at the time of the invasion to slightly more than 65%[4] percent by 1941.

The 1918–1929 period under the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was a time of persecution of the Kosovar Albanians. Kosovo was split into four counties - three being a part of official Serbia: Zvečan, Kosovo and southern Metohija; and one in Montenegro: northern Metohija. However, the new administration system since 26 April 1922 split Kosovo among three Regions in the Kingdom: Kosovo, Rascia and Zeta.

In 1929 the Kingdom was transformed into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The territories of Kosovo were split among the Banate of Zeta, the Banate of Morava and the Banate of Vardar. The Kingdom lasted until the World War II Axis invasion of April 1941.

After the Axis invasion, the greater part of Kosovo became a part of Italian-controlled Fascist Albania, and a smaller, Eastern part by the Nazi-Fascist Tsardom of Bulgaria and Nazi-German-occupied Kingdom of Serbia. Since the Albanian Fascist political leadership had decided in the Conference of Bujan that Kosovo would remain a part of Albania they started expelling the Serbian and Montenegrin setlers "who had arrived in the 1920s and 1930s"[5]. Prior to the surrender of Fascist Italy in 1943, the German forces took over direct control of the region. After numerous Serbian and Yugoslav Partisans uprisings, Kosovo was liberated after 1944 with the help of the Albanian partisans of the Comintern, and became a province of Serbia within the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia.

The Province of Kosovo was formed in 1945 as an autonomous region to protect its regional Albanian majority within the People's Republic of Serbia as a member of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia under the leadership of the former Partisan leader, Josip Broz Tito, but with no factual autonomy. After the Yugoslavia's name changed to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Serbia's to the Socialist Republic of Serbia in 1953, the Autonomous Region of Kosovo and gained inner autonomy in the 1960s.

In the 1974 constitution, the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo's government received higher powers, including the highest governmental titles - President and Premier and a seat in the Federal Presidency which made it a de facto Socialist Republic within the Federation, but remaining as a Socialist Autonomous Region within the Socialist Republic of Serbia. Serbian (called Serbo-Croatian at the time) and Albanian were defined official on the Provincial level marking the two largest linguistic Kosovan groups: Serbs and Albanians.

In the 1970s, an Albanian nationalist movement pursued full recognition of the Province of Kosovo as another Republic within the Federation, while the most extreme elements aimed for full-scale independence. Tito's arbitrary regime dealt with the situation swiftly, but only giving it a temporary solution.

In 1981 the Kosovar Albanian students organized protests seeking that Kosovo becomes a Republic within Yugoslavia. Those protests were harshly contained by the centralist Yugoslav and Serbian governments. In 1986, the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) was working on a document, which later would be known as the SANU Memorandum. An unfinished edition was filtered to the press. In the essay, SANU portrayed the Serbian people as a victim and called for the revival of Serb nationalism, using both true and greatly exaggerated facts for propaganda. During this time, Slobodan Milošević's rise to power started in the League of the Socialists of Serbia. Milošević used the discontent reflected in the SANU memorandum for his political goals.

Soon afterwards, as approved by the Assembly in 1990, the autonomy of Kosovo was revoked back to the old status. Milošević, however, did not remove Kosovo's seat from the Federal Presidency, installing in it his own supporters to seize more power in the Federal government. After Slovenia's secession from Yugoslavia in 1991, Milošević used the seat to attain dominance over the Federal government, outvoting his opponents.

Many Albanians organized a peaceful active resistance movement, following the job losses suffered by some of them. Albanian schools and the medical care system were shut down.

On July 2, 1990 an unconstitutional Kosovo parliament declared Kosovo an independent country, although this was not recognized by the Government. In September of that year, the parliament, meeting in secrecy in the town of Kačanik, adopted the Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo. Two years later, in 1992, the Parliament organized a referendum which was observed by international organisations but was not recognized internationally. With an 80% turnout, 98% voted for Kosovo to be independent. In the early nineties, Albanians organized a parallel state system which managed the non-violent resistance movement and organized a parallel system of education and healthcare, among other things. With the events in Bosnia and Croatia coming to an end, the Serb government started relocating Serbian refugees from Croatia and Bosnia to Kosovo. In a number of cases, Albanian families were expelled from their apartments to make space for the refugees[citation needed].

After the Dayton Agreement in 1995, Albanians organized into the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). Yugoslav forces allegedly committed war crimes in Kosovo, although the Serbian government claims that the army was only going after suspected Albanian "terrorists". This triggered a 78-day NATO campaign in 1999. During the conflict, some 12,000 Kosovars were killed, of whom 9,000-10,000 were Albanians and up to 700,000 Albanians expelled. Some 3,000 Albanians are still missing. According to OSCE numbers and Kosovar Albanian sources on population size and distribution, an estimated 45.7% of the Albanian population had fled Kosovo during the bombings (i.e. from 23 March to 9 June 1999).

International negotiations began in 2006 to determine the final status of Kosovo, as envisaged under UN Security Council Resolution 1244 which ended the Kosovo conflict of 1999. Whilst Serbia's continued sovereignty over Kosovo is recognised by the international community, a clear majority of the province's population would prefer independence. The UN-backed talks, lead by UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari, began in February 2006. Whilst progress was made on technical matters, both parties remained diametrically opposed on the question of status itself.[1] In February 2007, Ahtisaari delivered a draft status settlement proposal to leaders in Belgrade and Pristina, the basis for a draft UN Security Council Resolution which proposes 'supervised independence' for the province. As of early July 2007 the draft resolution, which is backed by the United States, United Kingdom and other European members of the Security Council, had been rewritten four times to try to accommodate Russian concerns that such a resolution would undermine the principle of state sovereignty [6]. Russia, which holds a veto in the Security Council as one of five permanent members, has stated that it will not support any resolution which is not acceptable to both Belgrade and Pristina [7].

See also: Kosovo status process

Culture

Culture-wise Albanians in Kosovo are very closely related to Albanians in Albania. Traditions and customs differ even from a town to town in Kosovo itself. The spoken dialect is Gheg, typical of northern Albanians. The education, books, media, newspapers, and official language of the institutions is the standard dialect of Albanian, which is closer to Tosk dialect.

Education is provided for all levels, primary, secondary, and university degrees. University of Priština is the public university of Kosovo, with several faculties and majors. The National Library (Alb: Bibloteka Kombëtare) is the main and the largest library in Kosovo, located in the centre of Priština. There are many other private universities, among them American University in Kosovo (AUK), etc, and many secondary schools and colleges such as Mehmet Akif College.

The most widespread religion among Albanians in Kosovo is Islam (mostly Sunni but with significant number of Bektashis). The other religion Kosovar Albanians practice is Roman Catholicism. There used to be a small Albanian Orthodox community, but their status is uncertain.

Kosovafilmi is the film industry, which releases movies in Albanian, created by Kosovo Albanian movie-makers.

The National Theatre of Kosovo (Alb: Teatri Kombëtar i Kosovës) is the main theatre where plays are shown regularly by Albanian and international artists.

Music

Music has always been part of the Albanian culture. Although in Kosovo music is diverse (as it got mixed with the cultures of different regimes dominating in Kosovo), the Albanian authentic music (see World Music) does still exist. It is characterized by use of çiftelia (an authentic Albanian instrument), mandolina, mandola and percussion.

In Kosovo, except the modern music, the folk music is very popular. There are many folk singers and ensembles.

The classical music is very knowable in Kosovo. There are many classical instrumentists, ensembles etc.

The modern music in Kosovo has its origin from the western countries. The main modern genres include: Pop, Hip Hop/Rap, Rock and Jazz. The most notable rock bands are: Gjurmët, Troja, Votra, Diadema, Humus, Asgjë sikur Dielli, Kthjellu, Gillespie, Cute Babulja, Babilon etc. Ilir Bajri is a notable jazz and electronic musician.

There are some notable music festivals in Kosovo:

- Rock për Rock - contains rock and metal music

- Polifest - contains all kinds of genres (usually hip hop, commercial pop, and never rock or metal)

- Showfest - contains all kinds of genres (usually hip hop, commercial pop, unusually rock and never metal)

- Videofest - contains all kinds of genres

- Kush Këndon Lutet Dy Herë - contains all kinds of genres which have Christian lyrics

Kosovo Radiotelevisions like RTK, 21 and KTV have their musical charts.

- See also: Kosovo's and Albania's musicians

Prominent individuals

Before 1950

- Gjon Buzuku, born in the 16th century a Catholic priest, born in Has, a region close to Prizren, the writer of one of the earliest books in Albanian, Meshari.

- Pjetër Bogdani, (1630-1689) born in Has, a Catholic bishop and author of the old Albanian literature as well as an eminent fighter against the Ottoman Empire

- Isa Boletini, born in 1864, in Boletin, a village close to Mitrovica, one of the main commanders of Albanian troops who fought against Ottoman, Bulgarian, Serbian Empire troops in the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century.

- Hasan Prishtina (1873 - 1933) born in Vushtri/Vučitrn, an Albanian intellectual, and organizer of Albanian movements against Ottomans and other regimes installed in Kosovo, during the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century.

- Bajram Curri a freedom fighter, and nationalist, born in Gjakovë/Đakovica in 1862.

- Sulejman Vokshi (1815 - 1890) born in Gjakovë/Đakovica, one of the main commanders, and leaders of the armed forces organized by the League of Prizren.

- Valbona Gusija, born in 1968 in Prishtina/Priština, is one of the pioneers of the Albanian social service movement in Canada.

Current

- Nexhmije Pagarusha, born in May 7, 1933, singer and actress

- Ibrahim Rugova former President of Kosovo and founder and head of LDK and organizer of the peaceful resistance of Kosovo Albanians from 1990 - 1999 (died of lung cancer on Jan 21, 2006).

- Adem Jashari, (1955-1998), born in Prekaz, a distinguished commander of the Kosovo Liberation Army, killed during the 1999 Kosovo War.

- Veton Surroi former publicist of Koha Ditore, formerly the political leader of the ORA reformist party.

- Nexhat Daci Ph.D. in Chemistry, university professor, and former speaker of Assembly of Kosovo, member of the LDK.

- Agim Çeku former Colonel of the Croatian Army, former military commander of KLA and later of the KPC, and currently Prime Minister of Kosovo.

- Rifat Kukaj (25 October 1938 – September 11, 2005) one of the most successful writers in Albanian literature for children. He was born in Tërstenik, Drenica region of Kosovo.

- Anton Çetta born in Gjakovë/Đakovica, patriot, folklorist, academician, university professor. He was the founder of the Reconciliation Committee for erasing blood feuds in Kosovo (Alb: Komiteti per pajtimin e gjaqeve ne Kosovë). He is famous for having settled almost all of blood feuds among Albanians in Kosovo, in the 1990s.

- Albin Kurti a former leader of the student protests during late 90s, currently the leader of the VETËVENDOSJE! (Self-determination) movement, which fights for the right of Albanians in Kosovo for self-determination on the future of Kosovo.

- Xhevad Prekazi football player

References

- ^ "UN frustrated by Kosovo deadlock ", BBC News, October 9, 2006.

See also

- Albanians

- Kosovo

- Albanians in the Republic of Macedonia

- Albanians in Montenegro

- Demographic history of Kosovo

| Ethnic groups in Kosovo |