2007 Slovenian presidential election

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

|

UN Member State |

The 2007 Slovenian presidential election was held in two rounds, on 21 October 2007 and 11 November 2007, in order to elect the successor to the second President of Slovenia Janez Drnovšek for a five-year term.[1] France Cukjati, the President of the National Assembly, called the election on 20 June 2007.[2]

Seven candidates competed in the election's first round;[3] three entered the race as independent candidates, the other four were supported by political parties. Several political events, as well as tension between the Government and the political opposition, overshadowed the campaign. The front runner Lojze Peterle, supported by the governing conservative coalition, won the first round with far fewer votes than predicted by opinion polls. Left-wing candidate Danilo Türk won the second round with 68.03% of the vote.[4]

In a referendum called by the National Council, and held on the same day as the second round of the presidential election, the electorate voted to overturn a law providing for the nationalization of citizens' share in the major national insurance company. Nearly three quarters of the votes were cast against the law.[4] After both election and referendum results were announced, the Prime Minister Janez Janša announced his possible resignation, following what he perceived to be a heavy defeat for the Government. Later, the Government won a vote of confidence in the National Assembly.

Background

The role of the president of Slovenia is mainly ceremonial. One of the president's duties is to nominate the Prime Minister, after consulting with political groups represented in the National Assembly. The president also proposes candidates for various state offices, as well as judicial appointments to the Constitutional and Supreme Court, which must be approved by the National Assembly. In rare circumstances, the president possesses the power to pass laws and dissolve the National Assembly. The President is also the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. Unlike the majority of the government, which is chosen by the National Assembly and elected through proportional representation, the president is directly elected by the majority of Slovenian voters.[5]

The previous presidential election in 2002 brought major changes to Slovenian politics. The former president Milan Kučan, in office since the first free elections held in the Republic of Slovenia in April 1990 (before the country's independence from Yugoslavia), was forbidden by the constitution from running for President again, and announced his retirement from active politics. Prime Minister Janez Drnovšek of the Liberal Democracy of Slovenia stood for the office, comfortably winning the runoff against conservative candidate Barbara Brezigar.[6]

The 2004 legislative election brought further changes and a political swing to the right. Janez Janša, the leader of a right-wing coalition, formed the new government. In Slovenia, this was the first time after 1992 that the President and the Prime Minister had represented opposing political factions for more than a few months. Between 2002 and 2004, the relationship between President Drnovšek and Janez Janša, then leader of the opposition, were considered more than good [7] and in the first year of cohabitation, no major problems arose.

In the beginning of his term, Drnovšek, who was ill with cancer, stayed out of public view. When he reemerged in late 2005 he had changed his lifestyle: he became a vegan, moved out of the capital into the countryside, and withdrew from party politics completely, ending his already frozen membership in the Liberal Democracy. Drnovšek's new approach to politics prompted one political commentator to nickname him "Slovenia's Gandhi".[8][9]

The relationship between Drnovšek and the government quickly became tense. Disagreements began with Drnovšek's initiatives in foreign politics, aimed at solving major foreign conflicts, including those in Darfur and Kosovo.[9] Initially, these initiatives were not openly opposed by the Prime Minister, but were criticized by the foreign minister Dimitrij Rupel,[10] Drnovšek's former collaborator and close political ally until 2004. [11] The disagreements moved to issues of domestic politics in October 2006, when Drnovšek publicly criticised the treatment of the Roma family Strojans. The neighborhood had forced the Strojans to relocate, which in turn subjected them to police supervision and limitation of movement.[8] The disagreements however escalated when the parliamentary majority repeatedly rejected President's candidates for the Governor of the Bank of Slovenia, beginning with the rejection of incumbent Mitja Gaspari.[12] The friction continued over the appointment of other state official nominees, including Constitutional Court judges. Although the President's political support suffered after his personal transformation, the polls nevertheless showed public backing of the President against an increasingly unpopular Government.[13][9] The tension reached its height in May 2007, when the newly appointed director of the Slovenian Secret Service Matjaž Šinkovec unclassified several documents from the period before 2004, revealing, among other, that Drnovšek had used secret funds for personal purposes between 2002 and 2004. The President reacted with a harsh criticism of the government's policies, accusing the ruling coalition of abusing its power for personal delegitimation[14] and labeled the Prime Minister as "the leader of the negative guys".[15] After years of speculation about his health and intentions, Janez Drnovšek announced in February 2007 that he would not run for president again.[16]

Candidates

Requirements for candidacy

Under Slovenian Election Law, each political party can support only one candidate. Two or more parties can support a single candidate together. In such cases, the candidacy has to be supported either by three members of the National Assembly or by 3,000 voters, signing a special petition form. The other option for a candidate is to run as an independent without party support, relying entirely on public support; in such case, 5,000 support votes are required.[17]

Leading candidates

Lojze Peterle, a conservative member of the European parliament and first democratically elected Prime Minister of Slovenia (1990-1992), announced his candidacy in November 2006, making him the first official candidate.[18] He was endorsed by the three government right-wing parties, New Slovenia (NSi), Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS), and Slovenian People's Party (SLS).[19]

Drnovšek's announcement that he would not run for president again led to expectations that the Social Democrats (SD) would nominate their leader Borut Pahor and indeed Pahor confirmed that he was ready to run for the office.[20][21] The Social Democrats had become the most popular party in opinion polls and were considered the likely winners at the next general election in 2008; opinion polls indicated that Pahor would easily win the presidential election.[22] However, after months of mixed signals, Pahor finally announced that he would instead concentrate on the general election and would not run for the mostly ceremonial office of the president.[23]

The Social Democrats then nominated Danilo Türk, a former Slovenian ambassador and high official in the United Nations, who at the time was a professor at the University of Ljubljana's Faculty of Law.[24] Türk's candidacy was also endorsed by Zares, a splinter party made up of many of the members of the National Assembly who left the Liberal Democracy, which quickly disintegrated in opposition after 10 years in government,[25] and the pensioners' party DeSUS.[26] Türk also gained support from Active Slovenia (AS) and the Party of Ecological Movements (SEG), two parties not represented in the National Assembly.[27]

Liberal Democracy of Slovenia (LDS), which had earlier discussed the candidacy with Danilo Türk, subsequently nominated Mitja Gaspari, the former Governor of the Bank of Slovenia.[28] Gaspari had earlier had discussions with the Social Democrats about the candidacy.

The Slovenian National Party (SNS) nominated its leader, Zmago Jelinčič.[29] Jelinčič had already run for the office at the 2002 election, finishing third with 8.51% of the votes.[6]

Peterle, Türk and Gaspari all decided to enter the election as independent candidates and all managed to collect enough nominating votes with Peterle reaching the required number within the first 4 hours of the nominating process.[30] Jelinčič was supported by his fellow party members.[30]

Early polls indicated that Peterle, who had been campaigning for months and had cultivated the image of a "man of the people", would win the election in a runoff against Türk or possibly Gaspari.[31][32]

-

Lojze Peterle, independent candidate, supported by NSi, SDS and SLS

-

Danilo Türk, independent candidate, supported by SD, DeSUS, Zares, AS and SEG

-

Mitja Gaspari, independent candidate, supported by LDS

-

Zmago Jelinčič, candidate of SNS

Other candidates

Other candidates, none of whom were expected to win a significant share of votes, were Darko Krajnc of the formerly parliamentarian Youth Party of Slovenia, the disabled rights activist Elena Pečarič, and Monika Piberl, supported by the Women's Voice of Slovenia party.[33] Pečarič was supported by non-aligned Majda Širca, independent Slavko Gaber and Roberto Battelli, representative of the Italian minority in Slovenia.[34] Krajnc and Piberl were supported by non-parliamentary political parties so they only needed to collect 3,000 support votes.[35][36]

Several other candidates publicly announced their intention to run for the office. Jože Andrejaš, Jožef Horvat, Matej Sedmak, Marjan Beranič, Marko Kožar and Pavel Premrl failed to gather sufficient public support or later decided to withdraw from the race.[37] Artur Štern, after leading a spoof campaign, announced that he was in fact performing a media experiment, and was making a movie to address the fact that there are no minimum requirements to announce candidacy.[38]

First round campaign

The official election campaign began in late September 2007. The campaigns of the three front runners were based mostly on the personal appeal of the candidates, with few concrete statements about political issues. Zmago Jelinčič led an aggressive campaign, focusing on denouncing the three front runners, the Government, the ethnic and religious minorities, the Roman Catholic Church, and demanding an aggressive policy towards neighbouring Croatia.[39]

The candidates appeared in televised debates during which they discussed various topics, including the rules governing the voting of non-resident nationals, which had been changed by the National Electoral Commission during the campaign. Before the campaign, non-resident nationals who wanted to cast their votes as absentee ballots had been obliged to request voting materials, but the Commission had introduced a new system in which such materials were sent to all non-residents entered in the electoral register, whether they had asked for them or not. Opposition parties, representing the left-wing of Slovenian politics, disliked this move because the record of voters' addresses was not always reliable, and also because the rules had been changed after the campaign had already started.[40] They particularly opposed the change because voters from abroad seemed to favor right-wing parties, so that in the event of a very close ballot, votes from non-residents could tip the scale in favour of Peterle.[41]

Other events overshadowed the campaign. During the summer, journalists Matej Šurc and Blaž Zgaga launched a Petition Against Censorship and Political Pressures on Journalists in Slovenia, alleging government interference with journalism. The petition was signed by hundreds of Slovenian journalists from the mainstream media.[42] It was sent to the heads of state, prime ministers and parliamentary speakers of all EU member states during the campaign. Following the petition, the International Press Institute (IPI) sent a fact-finding mission to Ljubljana in November, to discuss the claims made in the petition with members of the Slovenian media. The contents of the mission's report remain confidential, but IPI called for the establishment of an independent commission to investigate the claims further.[43]

Another event which attracted much debate was the Supreme Court's annulment of the 1946 war crimes conviction of Gregorij Rožman. Rožman was the Catholic bishop of Ljubljana who had been found guilty of war crimes and treason during World War II as a result of his collaboration with Italian and German occupation forces. Several attempts during the 1990s to review the trial had failed. This had led to Janša's government changing the law, enabling the religious communities to request a review of trials of their deceased members, something which had previously been reserved only for close relatives. After the Archdiocese of Ljubljana initiated the review, the Supreme Court annulled the 1946 trial on procedural grounds, effectively rehabilitating Rožman, a decision that caused much controversy. This proved harmful for Peterle's campaign, as he was closely associated with the Catholic Church.[44] When asked about the Rožman case in a TV debate, Peterle confined himself to remarking that he was a supporter of the rule of law, that the war had divided the nation and that Rožman had played some part in that.[45]

The last opinion polls published before the first round predicted a runoff between Peterle, who would win 40%, and either Türk or Gaspari. The latter each predicted to received 20–25%; most polls predicted a substantially larger share for Türk.[46]

First round results and reactions

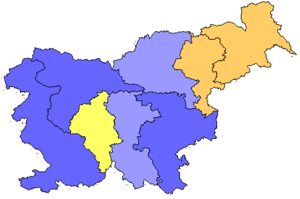

Lojze Peterle: 20–30% (pastel blue), 30–40% (dark blue)

Mitja Gaspari: 20–30% (yellow)

Zmago Jelinčič: 20–30% (orange)

The first round, held on 21 October, brought unexpected results. Contrary to predictions, Peterle won less than 29% of the vote, with Türk and Gaspari finishing a close second and third, respectively. Jelinčič, who according to opinion polls was expected to win around 12% of the vote, actually won over 20%, finishing first in two of Slovenia's eight electoral units.[4] Prime Minister Janez Janša blamed Peterle's poor showing on certain topics that were brought up during the campaign by "hidden centres of power". This was a reference to the journalists' petition, the timing of the Supreme Court's decision on the Rožman case and misinterpretation of Janša's and Minister of Economy Andrej Vizjak's remarks on reasons for Slovenia's high inflation in 2007.[47]

Runoff campaign

Following the unexpected results of the first round, new opinion polls showed major changes, giving Türk a large lead over Peterle.[48] Liberal Democracy of Slovenia, which supported Gaspari in the first round, announced it would support Türk in the second.[49]

After the surprise gains of the flamboyant Jelinčič in the first round, the campaigns of both candidates opted for more concrete political statements in public campaigning and debates. Peterle replaced the head of his campaign, and concentrated on questioning Türk's role in the 1991 secession from Yugoslavia. Peterle alleged that at the time when he, as Prime Minister, struggled for Slovenia's independence, Türk continued to act as an official representative of Yugoslavia in international institutions.[50] The campaign was backed by the Prime Minister Janša and the Foreign Minister Dimitrij Rupel who went so far as to confirm Peterle's claims on the Foreign Ministry's official website.[51] Türk denied the allegations, pointing to his opinion piece in the International Herald Tribune advocating international recognition of Slovenia, and the fact that it was Rupel himself who in 1992 appointed Türk as the Ambassador to the UN and praised him for his service to the country.[50][52] The new strategy appeared to backfire, and the polls before the runoff predicted that Türk would win between 63% and over 70% of the vote.[53][54]

Final results and reactions

The runoff was held on 11 November 2007. Exit poll results published at the closing of the vote predicted a victory for Türk, with 69% of the vote.[55] Peterle conceded immediately. In his first statements, Peterle said his defeat was a vote against the ruling Janša government, and that he had expected a better result. He added, however, that he would have regretted it if he had not decided to run for the office.[56] By midnight, unofficial results from the Electoral Commission gave Türk a lead of 68% vs. 32%, with Peterle narrowly winning in four of Slovenia's 88 electoral districts.[4]

Two days after the election, Prime Minister Janša announced that he might resign following what was perceived as a heavy defeat for the Government: "We will analyze the situation further, but all possibilities are open, including a resignation of the Government." He said that "it is particularly worrying that a lot of energy was invested in blackening the Government abroad", claiming his opponents portrayed Slovenia "as Belarus" or some other authoritarian country. The opposition parties said that talk of resignation just weeks before Slovenia took over European Union presidency was irresponsible and unwise,[57] but the Prime Minister called a vote of confidence for 19 November 2007.[58] The Government won the confidence vote, but support for the ruling SDS subsequently reached an all-time low, with only 18% of voters intending to vote for it in the fall 2008 election.[59]

Reactions to Türk's victory from international media were positive. The Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung described him as "more or less the ideal man for the job".[60] The media focused on the landslide victory that was perceived to be a severe defeat for Janša’s centre-right coalition.[61][62] Since the EU presidency was closing, Türk's diplomatic background was put forward. "Slovenia is your solid, faithful and credible partner. Rely on us, and we'll be a good president of the European Union next year," Türk said.[62] Türk was also expected to maintain Slovenia's alliance with the United States even though he was highly critical of the war in Iraq, as Al Jazeera reported.[63]

On 22 December, Türk was sworn in as the President of the Republic of Slovenia. In his inaugural address, he thanked his predecessor Janez Drnovšek for his contribution to success and respect of Slovenia. Later, he also stated that he would work closely with Janša's government during Slovenia's six-month EU presidency.[64]

Detailed results

Template:Slovenian presidential election, 2007

References

- ^ "Slovenian presidential election to be held in October". Xinhua. 2007-07-20. Retrieved 2008-09-21.

- ^ "Volitve čez tri mesece" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2007-06-20. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Sedem kandidatov na volitve" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b c d "Volitve predsednika republike 2007" (in Slovene). 2007-11-11. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Slovenia Country Brief". Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ^ a b "Poročilo o izidu volitev predsednika republike" (in Slovene). Republiška volilna komisija. 2007-12-10. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Iskalci vizije" (in Slovene). Mladina. 2003. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b "Slovenian President Finds Peace and Wants to Share It". The New York Times. 2006-09-09. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ a b c "All hail the mystic President". Times Online. 2007-11-15. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ "Kosovska bitka: Drnovšek proti Ruplu" (in Slovene). Mladina. 2005. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Rop: Rupel se je odločil po svoje" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2004-06-26. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Gaspari Three Votes Short of Winning Second Term". Government communication office. 2007-02-06. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ "Lepotica in zver" (in Slovene). Mladina. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "'Vlada me skuša zlomiti'" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2007-05-18. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Obletnica Dnevnikovega razkritja: Po letu dni afera Sova še vedno brez epiloga" (in Slovene). Dnevnik. 2008-03-21. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Drnovšek ne bo znova kandidiral" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2006-06-26. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Zakon o volitvah predsednika republike (ZVPR)" (in Slovene). Uradni list RS, št. 39/1992. 1992-08-07. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Peterle kandidat za predsednika države" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2006-11-02. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Enotna podpora Peterletu" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2007-06-15. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Pahor pripravljen kandidirati za predsednika države" (in Slovene). Finance. 2007-03-31. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Pahor bi kandidiral za predsednika" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2007-03-04. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Pahor vodi v bitki za predsednika" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2007-05-26. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Pahor s SD-jem na parlamentarne volitve" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2007-06-22. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Türk tudi uradno s podporo SD-ja" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2007-07-13. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Tudi v Zares bodo podprli Türka" (in Slovene). Finance. 2007-07-12. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "DeSUS soglasno za Danila Türka" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2007-08-27. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Gaspari in Türk začenjata kampanjo" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2007-06-26. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Gaspari z LDS v predsedniško tekmo" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Jelinčič bi bil rad Drnovšek" (in Slovene). Finance. 2007-05-25. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b "Peterle in Jelinčič prva uradna kandidata" (in Slovene). Žurnal24. 2007-09-06. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Jelinčič najbolj napredoval" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2007-10-06. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Alojz Peterle and Danilo Türk to face each other in the second round of the presidential election in Slovenia on 11th November". The Robert Schuman Foundation. 2007-10-21. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ "Zakaj so kandidirali?" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2008-08-21. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Pečaričeva peta kandidatka" (in Slovene). Žurnal24. 2007-09-20. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Krajnc vložil kandidaturo" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2007-09-25. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Monika Piberl kot sedma v boj" (in Slovene). Finance. 2007-10-01. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Predsedniške volitve 2007" (in Slovene). Žurnal24. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Šternova filmska kampanja" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2007-09-13. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Jelinčič: Slovenija potrebuje patriota" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2007-09-20. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Opozicijski poslanci izpodbijajo določbo o glasovanju iz tujine" (in Slovene). Dnevnik. 2007-06-18. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Kaj bo, če bo tisoč glasov razlike?" (in Slovene). Mladina. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Peticija zoper cenzuro". Matej Šurc, Blaž Zgaga (in Slovene). 2007-10-21. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "World Press Freedom Review". International Press Institute. 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ^ One of the controversies during the short-lived centre righ government of Andrej Bajuk's government was the participation of several leading members of the coalition in a ceremony in June 2000. The ceremony honored the members of the Slovene Home Guard, a collaborationist militia, killed by the Communist regime in June 1945. At the ceremony, anthems of the Slovene Home Guard were sung. Among those attending were Prime Minister Andrej Bajuk, chairman of the National Assembly Janez Podobnik, Defense Minister Janez Janša, Foreign Minister Lojze Peterle, and Archbishop of Ljubljana Franc Rode. See Sabrina Ramet: Slovenia since 1990 Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ^ "Zadnje soočenje na POP TV" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ ""Peterle First, But runoff Likely in Slovenia"". Angus Reid Global Monitor. 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ "Janša upa na korekten drugi krog" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2007-10-23. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) Janša je tudi izpostavil, da so v zadnjih nekaj tednih različni vplivni centri iz ozadij sprožili teme, ki naj bi vplivale na izid. Med temi naj bi bile novinarska peticija, razveljavitev obsodbe škofu Rožmanu ter sprevračanje njegove izjave in izjave ministra Vizjaka o vzrokih za inflacijo. - ^ "Ankete kažejo na zmago Türka" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2007-10-27. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Türku tudi podpora LDS" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2007-11-06. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b "Fronta na liniji Türkove vloge v 90. letih" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2007-11-07. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ "Türk: Kaže, da se je nekomu zameglil razum" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2007-11-06. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Tuerk leads in Slovenia presidential runoff". B92. 2007-11-09. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ "Tuerk Surges Ahead in Slovenian runoff". Angus Reid Global Monitor. 2007-11-10. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ "Türku visoka zmaga za najvišji položaj" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2007-11-07. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Delovati moramo kot ekipa" (in Slovene). 24ur.com. 2007-11-12. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Slovenia's PM: Cabinet might resign after opposition candidate elected president". International Herald Tribune. 2007-11-13. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ "Slovenian PM seeks confidence vote after opposition candidate became president". International Herald Tribune. 2007-11-16. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ "Slovenian government survives confidence vote". EUbusiness.com. 2007-11-20. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ "In Slowenien setzt sich der Aussenseiter Türk durch" (in German). Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 2007-11-12. Retrieved 2008-09-16.Als einer der wenigen slowenischen Politiker mit internationaler Bekanntheit galt er in Hinblick auf Sloweniens nahende EU-Präsidentschaft als Idealbesetzung.

- ^ "Danilo Turk wins Slovenia presidential vote". AFP. 2007-11-11. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ a b "Turk elected president of Slovenia". France 24. 2007-11-11. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ "Ex-UN diplomat wins Slovenia polls". Al Jazeera. 2007-11-12. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ "Türk prisegel kot predsednik države" (in Slovene). Rtvslo.si. 2007-12-22. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)