Historical European martial arts

- HEMA redirects here. See HEMA (disambiguation) for other uses.

Historical European Martial arts are martial arts of European origin, often commonly used to refer to arts which were formerly practised, but have since died out or evolved into very different forms. Modern reconstructions of some of these arts exist and are practiced today. Historical European martial arts are often known as Western martial arts.

Antiquity to High Middle Ages (before 1350)

There are no known manuals predating the Late Middle Ages (except for fragmentary instructions on Greek wrestling, see P.Oxy. III 466), although Ancient and Medieval literature (e.g. Icelandic sagas and Middle High German epics) record specific martial deeds and military knowledge; in addition, historical artwork depicts combat and weaponry (e.g. the Bayeux tapestry, the Morgan Bible). Some researchers have attempted to reconstruct older fighting methods such as Pankration and gladiatorial combat by reference to these sources and practical experimentation, though such recreations necessarily remain more speculative than those based on actual instructions.

The so-called MS I.33 (also known as the Walpurgis or Tower Fechtbuch), dated to between ca. 1290 (by Alphonse Lhotsky) and the early to mid-14th century (by R. Leng, of the University of Würzburg), is the oldest surviving fechtbuch, teaching sword and buckler combat.

Late Middle Ages (1350 to 1500)

The central figure of late Medieval martial arts, at least in Germany, is Johannes Liechtenauer. Though no manuscript written by him is known to survive, his teachings were first recorded in the late 14th century MS 3227a. From the 15th century into the 17th, numerous Fechtbücher (German "fencing-books") were produced, of which some 55 are extant; a great many of these describe methods descended from Liechtenauer's.

Normally, several modes of combat were taught alongside one another, typically unarmed grappling (Kampfringen or abrazare), dagger (Degen or daga, often of the rondel variety), long knife (Messer) or Dussack, half- or quarterstaff, pole arms, longsword (langes Schwert, spada longa, spadone), and combat in plate armour (Harnischfechten or armazare), both on foot and on horseback. Some Fechtbücher have sections on dueling shields (Stechschild), special weapons used only in judicial duels. The long sword had a position of honour among these disciplines, and sometimes Historical European Swordsmanship (HES) is used to refer to swordsmanship techniques specifically.

Important 15th century German fencing masters include Sigmund Ringeck, Peter von Danzig, Hans Talhoffer and Paulus Kal, all of whom taught the teachings of Liechtenhauer. From the late 15th century, there were "brotherhoods" of fencers (Fechtbruderschaften), most notably the Marx brothers (attested 1474) and the Federfechter.

An early Burgundian French treatise is Le jeu de la hache ("The Play of the Axe") of ca. 1400.

The earliest master to write in the Italian was Fiore dei Liberi, commissioned by the Marquis di Ferrara. In approximately 1410, he documented comprehensive fighting techniques in a treatise entitled Flos Duellatorum covering grappling, dagger, arming sword, longsword, pole-weapons, armoured combat and mounted combat. The Italian school is continued by Filippo Vadi (1482-1487) and Pietro Monte (1492, Latin with Italian and Spanish terms)

Three early (before Silver) natively English swordplay texts exist, all very obscure and of uncertain date; they are generally thought to belong to the latter half of the 15th century.

Early Modern period (1500 to 1700)

In the 16th century, compendia of older Fechtbücher techniques were produced, some of them printed, notably by Paulus Hector Mair (in the 1540s) and by Joachim Meyer (in the 1570s).

In the 16th century German fencing had developed sportive tendencies. The treatises of Paulus Hector Mair and Joachim Meyer derived from the teachings of the earlier centuries within the Liechtenauer tradition, but with new and distinctive characteristics. The printed fechtbuch of Jacob Sutor (1612) is the last in the German tradition.

The Italian school is continued by the Dardi school, with masters such as Antonio Manciolino and Achille Marozzo. From the late 16th century, Italian rapier fencing attained considerable popularity all over Europe, notably with the treatise by Salvator Fabris (1606).

- Antonio Manciolino (1531) (Italian)

- Achille Marozzo (1536) (Italian)

- Angelo Viggiani (1551) (Italian)

- Camillo Agrippa (1553) (Italian)

- Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza (1569) (Spanish)

- Giacomo Di Grassi (1570) (Italian)

- Giovanni Dall’Agocchie (1572) (Italian)

- Henry deSainct Didier (1573) (French)

- Frederico Ghisliero (1587) (Italian)

- Vincentio Saviolo (1590) (Italian)

- George Silver (1599) (English)

- Luis Pacheco de Narváez (1600) (Spanish)

- Salvator Fabris (1606) (Italian)

- Nicoletto Giganti (1606) (Italian)

- Ridolfo Capo Ferro (1610) (Italian)

- Joseph Swetnam (1617) (English)

- Francesco Alfieri (1640) (Italian)

- Francesco Antonio Marcelli (1686) (Italian)

- Bondi' di Mazo (1696) (Italian)

Modern period (1700 to 1918)

The martial arts of the post-Renaissance period can be divided roughly into civilian duelling/self defence, sporting and military applications. There is considerable overlap between these classifications, however, in that some systems fit into more than one category.

Examples of martial arts practiced primarily by the military during this period include bayonet fencing, sabre fencing and the use of the lance by cavalry soldiers.

The duelling and self-defence categories include smallsword and later styles rapier fencing, walking-stick fighting and Bartitsu (an early hybrid of Eastern and Western schools popularized at the turn of the 20th century).

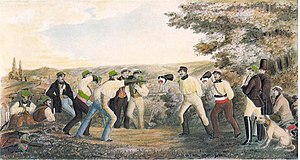

European combat sports of the 1700s to early 1900s include boxing, numerous regional forms of wrestling, the French kickboxing art of Savate, quarterstaff and singlestick fencing as well as stick fighting methods such as Jogo do Pau and Juego del Palo.

Some existing forms of European martial arts and combat sports can trace direct teacher-student lineages to the 19th century. Notable examples include the French kickboxing art of savate and the stick fighting methods of Portuguese Jogo do Pau, Italian Paranza and some styles of Canarian Juego del Palo. Direct continuity between the 18th and 19th centuries is more difficult to establish, but to a certain extent needs to be assumed by necessity: not least because the terminology of modern fencing is directly based on that introduced by Henry de Sainct-Didier in 1573. Likewise, academic fencing has a continuous tradition from the 16th century to the present day.

Reconstruction

Attempts at the reconstruction of historical fighting arts have occurred since the Victorian age most notably with the work of Egerton Castle and Alfred Hutton and of the French Academie D'Armes circa 1880-1914.

With the advent of the Society for Creative Anachronism (a historical re-enactment organization founded in 1966)

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2008) |

there was a renewed interest in the practice of historic fighting arts. Dividing their focus between Heavy Armored Fighting, to simulate early medieval warfare, and adapted sport Rapier fencing, to reenact later renaissance styles, the SCA regularly holds large re-creation scenarios, throughout the world. Their styles are often criticized by other groups as lacking discipline and scholarship. Since the organization is effectively a collection of like-minded hobbyists (with individual exceptions), participants who view their fighting sport objectively accept it as an outlet for stress and a source of pleasure, rather than a literal re-creation of historical fighting methods.

Another approach to the reconstruction of Medieval and Renaissance martial arts in the USA was pioneered by John Clements in the mid-1980s that focused on the analysis of the works of the historical masters and realistic martial practice. In the early-1990s Clements took over the leadership of The Association for Renaissance Martial Arts (ARMA), then known as HACA (The Historical Armed Combat Association), and focused the organization on a true martial arts approach to the reconstruction of these fighting arts. To ensure that a martial focus is maintained in its reconstruction efforts ARMA excludes all sport, re-enactment, role-playing, and persona activities, as well as choreographed theatrical swordplay. ARMA also started providing to the general public the fight books of the historical masters through its web site.

During this same period several other researchers in Europe and the United States started collecting and analysing the works of the historical masters. By the late 1990s there were more groups and organizations. Since 1999 a number of these groups have held the annual Western Martial arts Workshop (WMAW). In 2001 the Historical European Martial arts Coalition (HEMAC) was created to act as an umbrella organization for groups in Europe. Since 2002, the HEMAC has organized the annual International Historical European Martial arts Gathering in Dijon, France, hosted by De Taille et d'Estoc. A number of groups and organizations who were originally focused on Medieval and Renaissance re-enactment have since changed their focus to the study of Historical European Martial arts.

Organizations and Schools

The following is a limited list of organizations and schools that teach Historical European martial arts.

- Academy of Arms (Los Angeles)

- The Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts (AEMMA) (Toronto, Canada, since 1998)

- Academie Duello (Vancouver, Canada)

- The Association for Renaissance Martial Arts (ARMA)

- The Academy of Historical Fencing (AHF) (UK (Bristol & Newport))

- Magisterium (Czech Republic, combines historical reconstruction with scenic fencing)

- The Academy of European Swordsmanship (Canada, since 1994) [1]

- Academia Duellatoria (Oregon, USA, since 1995) [2]

- The New Dawn Duellist's Society (UK)

- The Italian Historical Fencing Federation (FISAS) (Italy, since 1995)[3]

- Sala d'Arme Achille Marozzo (Italy, since 1996)[4]

- The Martinez Academy of Arms (USA, since 1996)[5]

- The Chicago Swordplay Guild (USA, since 1998)[6]

- The Stoccata School of Defense (Australia, since 1998)[7]

- Collegium In Armis (Australia, since 2003)[8]

- Dreynschlag (Austria, since 1998) [9]

- Ochs Historische Kampfkünste (Germany, since 1999)[10]

- Mid-Atlantic Society for Historic Swordsmanship [11] (USA, since 1999)

- Die Freifechter (Germany, since 2000)[12]

- Zornhau (Germany, since 2000)[13]

- The Tattershall School of Defense (USA, since 2000)[14]

- The Cateran Society (USA, since 2000) [15]

- Schola Gladiatora (UK, since 2001) [16]

- The School of European Swordsmanship (Finland, since 2001)[17]

- The School of The Sword (UK, since 1998) [18]

- The Order of Seven Hearts (USA, since 2003)[19]

- Saint Martins Academy of Defense (USA, since 2001)[20]

- Unionen för Europeisk Stridskonst (Sweden, since 2001)[21]

- De Taille et d'Estoc (Dijon, France) [22]

- Historical European Martial Arts Coalition (HEMAC European umbrella organisation, since 2001)[23]

- The Medieval European Martial Arts Guild (USA, since 2006)[24]

- Retallack School of Arms (USA, since 2006)[25]

- De Zwaardkring Middeleeuwse Krijgskunsten (Netherlands) [26]

- Zwaard & Steen (Netherlands) [27]

- New York Historical Fencing Association (NYHFA) [28]

- Northwest Academy of Arms (Oregon, USA) [29]

- The Krigarenve (Mesa Arizona)

- KDF Nederland

- SwArta (Belgium) [30]

- Hema Cph (Denmark) [31]

- Stockholms Historiska Fäktsällskap (Sweden) [32]

- Göteborgs Historiska Fäktskola (Sweden) [33]

- Kalmars Historiska fäktskola (Sweden, since 2004) [34]

- Malmö Historiska Fäktskola (Sweden, since 1996)

- Angermannaorden (Sweden) [35]

- Mora Historiska Fäktskola (Sweden) [36]

- Varbergs Historiska Fäktskola (Sweden) [37]

- Uppsala Historiska Fäktskola (Sweden) [38]

Literature

- Anglo, Sydney. The Martial arts of Renaissance Europe. Yale University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-300-08352-1

- Terry Brown, English Martial arts (2002) Anglo-Saxon Books, ISBN 1-898281-29-7

- John Clements, Medieval Swordsmanship: Illustrated Methods and Techniques. Paladin Press, 1998). ISBN 1-58160-004-6

- John Clements, Renaissance Swordsmanship : The Illustrated Book Of Rapiers And Cut And Thrust Swords And Their Use. Paladin Press, 1997. ISBN 0-87364-919-2

- John Clements, et al. Masters of Medieval and Renaissance Martial Arts: Rediscovering The Western Combat Heritage. Paladin Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58160-668-3

- Gaugler, William. The History of Fencing : Foundations of Modern European Fencing. Laureate Press, 1997. ISBN 1-884528-16-3

- Hans Heim & Alex Kiermayer, The Longsword of Johannes Liechtenauer, Part I (DVD), ISBN 1-891448-20-X

- Tommaso Leoni, The Art of Dueling (2005), ISBN 1-891448-23-4

- David James Knight and Brian Hunt, Polearms of Paulus Hector Mair, Paladin Press (2008), ISBN 978-1-58160-644-7.

- David Lindholm & Peter Svärd, Sigmund Ringeck's Knightly Art of the Longsword, Paladin Press (2003), ISBN 1-58160-410-6

- David Lindholm & Peter Svärd. Knightly Arts of Combat - Sigmund Ringeck's Sword and Buckler Fighting, Wrestling, and Fighting in Armor. Paladin Press, 2006. ISBN 1-58160-499-8

- David Lindholm, Fighting with the Quarterstaff, (2006), ISBN 1-891448-36-6

- Brian R. Price, ed. Teaching & Interpreting Historical Swordsmanship (2005), ISBN 1-891448-46-3

- Christopher Thompson, Lannaireachd: Gaelic Swordsmanship (2001), ISBN 1-59109-236-1

- Christian Henry Tobler, Secrets of German Medieval Swordsmanship (2001), ISBN 1-891448-07-2

- Christian Henry Tobler, Fighting with the German Longsword (2004), ISBN 1-891448-24-2

- Jason Vail, Medieval and Renaissance Dagger Combat (2006) Paladin Press

- Guy Windsor, The Swordsman's Companion: A Modern Training Manual for Medieval Longsword (2004), ISBN 1-891448-41-2

- Grzegorz Zabinski and Bartlomiej Walczak. The Codex Wallerstein : A Medieval Fighting Book from the Fifteenth Century on the Longsword, Falchion, Dagger, and Wrestling. Paladin Press, 2002. ISBN 1-58160-339-8

See also

- Swordsmanship

- German school of swordsmanship

- Italian school of swordsmanship

- Spanish school of swordsmanship

- Combat reenactment

External links

- A Chronological History of the Martial arts and Combative Sports 1350–1699 by Joseph R. Svinth

- The Historical European Martial arts Coalition. A Europe-wide coalition of clubs and researchers.

- The Association for Historic FencingUnited States Educational Non-Profit

- The Journal Of Western Martial arts

- The Raymond J. Lord Collection of Historical Combat Treatises

- map of schools and groups in Western Europe (google maps, maintained by arsgladii.at)

- Western Martial Arts Illustrated magazine