Mount Kenya

| Mount Kenya | |

|---|---|

|

Mount Kenya is the highest mountain in Kenya and the second highest in Africa, after Kilimanjaro.[3] The highest peaks of the mountain are Batian (5,199 metres (17,057 ft)), Nelion (5,188 metres (17,021 ft)) and Point Lenana (4,985 metres (16,355 ft)). Mount Kenya is located in central Kenya, just south of the equator, around (150 kilometres (93 mi)) north-northeast of the capital Nairobi.[3]

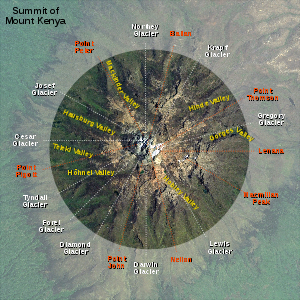

Mount Kenya is a stratovolcano created appxomiately 3 million years after the opening of the East African rift.[5] It was covered by an ice cap for thousands you years. This has resulted in very eroded slopes[6] and numerous valleys radiating from the centre.[4] There are currently 11 small glaciers. The mountain is an important source of water for much of Kenya.[7]

The volcano was discoved by Europeans in 1849 by Johann Ludwig Krapf,[8] but the scientific community remained skeptical about his reports of snow and ice so close to the equator.[9] The existence of Mount Kenya was confirmed in 1883 and it was first explored in 1887.[10] The summit was finally climbed by a team led by Halford John Mackinder in 1899.[11] Today there are many walking routes, climbs and huts on the mountain.[2]

There are eight distinct vegetation bands from the base to the summit.[12] The lower slopes are covered by different types of forest. Many species are endemic or highly characterestic of Mount Kenya such as the lobelias, the senecios and the rock hyrax.[13] Because of this, an area of 715 km² (276 mi²) around the centre of the mountain is designated a National Park[14] and listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[15] The park receives over 15,000 visitors per year.[7]

Mount Kenya National Park

Mount Kenya National Park, established in 1949, protects the region surrounding the mountain. Initially is was a forest reserve before being announced as a national park. Currently the national park is within the forest reserve which encircles it.[16] In April 1978 the area was designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.[17] The national park and the forest reserve, combined, became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997.[15]

The Government of Kenya had four reasons for creating a national park on and around Mount Kenya. These were the importance of tourism for the local and national economies, to preserve an area of great scenic beauty, to conserve the biodiversity within the park, and to preserve the water catchment for the surrounding area.[7]

Exploration

European discovery

Mount Kenya was the second of the three highest peaks in Africa to be seen for the first time by European explorers. The first European to see it was Dr Johann Ludwig Krapf, a German missionary, from Kitui in 1849,[18] a town 160 km (100 miles)[3] away from the mountain. The discovery was made on 3 December 1849,[8] a year after the discovery of Kilimanjaro.

Dr Krapf was told by people of the Embu tribe that lived around the mountain that they did not ascend high on the mountain because of the intense cold and the white matter that rolled down the mountains with a loud noise. This led him to infer that glaciers existed on the mountain.[18] The Kikuyu confirmed these happenings.

Dr Krapf also noted that the rivers flowing from Mt Kenya, and other mountains in the area, were continuously flowing. This was very different from the other rivers in the area, which swelled up in the wet season and completely dried up after the rainy season had ended. As the streams flowed even in the driest seasons he concluded that there must be a source of water up on the mountain, in the form of glaciers.[18] He believed the mountain to be the source of the White Nile.[19]

In 1851 Krapf returned to Kitui. He travelled 40 miles closer to the mountain, but did not see it again. In 1877 Hildebrandt was in the Kitui area and heard stories about the mountain, but also did not see it. Since there were no confirmations to back up Krapf's claim people began to be suspicious.[9]

Eventually, in 1883, Joseph Thomson passed close by the west side of the mountain and confirmed Krapf's claim. He diverted his expedition and reached 2743 m (9,000 ft) up the slopes of the mountain but had to retreat because of trouble with local people.[20] However, the first true European exploration of the mountain was achieved in 1887 by Count Samuel Teleki and Ludwig von Höhnel. He managed to reach 4350 m (14,270 ft) on the south western slopes.[10] On this expedition they believed they had found the crater of a volcano.

In 1892, Teleki and von Höhnel returned to the eastern side, but were unable to get through the forest.[13]

Finally, in 1893, an expedition managed to ascend Mount Kenya as far as the glaciers. This expedition was travelling from the coast to Lake Baringo in the Rift Valley, and was led by Dr John W Gregory, a British geologist. They managed to ascend the mountain to around 4730 m (15,520 ft), and spent several hours on the Lewis Glacier with their guide. On his return to Britain, Gregory published papers and a narrative account of his achievements.[21]

George Kolb, a German physician, made expeditions in 1894 and 1896[21] and was the first to reach the moorlands on the east side of the mountain. However, far more exploration was achieved after 1899 when the railway was completed as far as the site of Nairobi.[21] Access to the mountain was far easier from here than from Mombasa on the coast.[11]

Mackinder's Expedition

On 28 July 1899,[11] Sir Halford John Mackinder set out from the site of Nairobi on an expedition to Mt Kenya. The members of the expedition consisted of 6 Europeans, 66 Swahilis, 2 tall Maasai guides and 96 Kikuyu. The Europeans were Campbell B. Hausberg, second in command and photographer, Douglas Saunders, botanist, C F Camburn, taxidermist, Cesar Ollier, guide, and Josef Brocherel, guide and porter.[11]

The expedition made it as far as the mountain, but encountered many difficulties on the way. The country they passed through was full of plague and famine. Many Kikuyu porters tried to desert with women from the villages, and others stole from the villages, which made the chiefs very hostile towards the expedition. When they reached the base camp on 18 August,[11] they could not find any food, had two of their party killed by the local people, and eventually had to send Saunders to Naivasha to get help from Captain Gorges, the Government Officer there.[11]

Mackinder pushed on up the mountain, and established a camp at 3142 m (10,310 ft)[11] in the Höhnel Valley. He made his first attempt on the summit on 30 August with Ollier and Brocherel up the south east face, but they had to retreat when they were within 100 m (yds) of the summit of Nelion due to nightfall.

On 5 September, Hausberg, Ollier and Brocherel made a circuit of the main peaks looking for an easier route to the summit. They could not find one. On 11 September Ollier and Brocherel made an ascent of the Darwin Glacier, but were forced to retreat due to a blizzard.[11]

When Saunders returned from Naivasha with the relief party, Mackinder had another attempt at the summit with Ollier and Brocherel. They traversed the Lewis Glacier and climbed the south east face of Nelion. They spent the night near the gendarme, and traversed the snowfield at the head of the Darwin Glacier at dawn before cutting steps up the Diamond Glacier. They reached the summit of Batian at noon on 13th September, and descended by the same route.[11]

1900-1930

After the first ascent of Mt Kenya there were fewer expeditions there for a while. The majority of the exploration until after the First World War was by settlers in Kenya, who were not on scientific expeditions. A Church of Scotland mission was set up in Chogoria, and several Scottish missionaries ascended to the peaks, including Rev Dr. J. W. Arthur, G. Dennis and A. R. Barlow. There were other ascents, but none succeeded in summitting Batian or Nelion.[21]

New approach routes were cleared through the forest, which made access to the peaks area far easier. In 1920, Arthur and Sir Fowell Buxton tried to cut a route in from the south, and other routes came in from Nanyuki in the north, but the most commonly used was the route from the Chogoria mission in the east, built by Ernest Carr. Carr is also credited with building Urumandi and Top Huts.[21]

On 6 January 1929 the first ascent of Nelion was made by Percy Wyn-Harris and Eric Shipton. They climbed the Normal Route, then descended to the Gate of Mists before ascending Batian. On the 8 January they reascended, this time with G. A. Sommerfelt, and in December Shipton made another ascent with R. E. G. Russell. They also made the first ascent of Point John. During this year the Mountain Club of East Africa was formed.[21]

At the end of July 1930, Shipton and Bill Tilman made the first traverse of the peaks. They ascended by the West Ridge of Batian, traversed the Gate of Mists to Nelion, and descended the Normal Route. During this trip, Shipton and Tilman made first ascents of several other peaks, including Point Peter, Point Dutton, Midget Peak, Point Pigott and either Terere or Sendeyo.[22]

1931 to present day

In the early 1930s there were several visits to the moorlands around Mt Kenya, with fewer as far as the peaks. Raymond Hook and Humphrey Slade ascended to map the mountain, and stocked several of the streams with trout. By 1938 there had been several more ascents of Nelion. In February Miss C Carol and Mtu Muthara became the first woman and African respectively to ascend Nelion, in an expedition with Noel Symington, author of The Night Climbers of Cambridge, and on 5 March Miss Una Cameron became the first woman to ascent Batian.[21]

During the Second World War there was another drop in ascents of the mountain. Perhaps the most notable of this period is that of three Italian Prisoners of War, who were being held in Nanyuki, and escaped to climb the mountain before returning to the camp and "escaping" back in. No Picnic on Mount Kenya tells the story of the prisoners' exploit.[23]

In 1949 the Mountain Club of Kenya split from the Mountain Club of East Africa, and the area above 3,400 m (11,150 ft) was designated a National Park.[21] A road was built from Naro Moru to the moorlands allowing easier access.

Many new routes were climbed on Batian and Nelion in the next three decades, and in October 1959 the Mountain Club of Kenya produced their first guide to Mount Kenya and Kilimanjaro.[22] In the early 1970s the Mount Kenya National Park Mountain Rescue Team was formed, and by the end of the 1970s all major routes on the peaks had been climbed.[22]

In 1997 Mount Kenya was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[15]

On July 19 2003, a South African registered aircraft, carrying 12 passengers and two crew, crashed into Mount Kenya at Point Lenana: nobody survived.[24][25] This was not the first aircraft lost on the mountain; there is also the wreckage of at least one helicopter that crashed before 1972.[26]

Local culture

The main tribes living around Mount Kenya are Kĩkũyũ, Ameru, Embu and Maasai. They all see the mountain as an important aspect of their cultures.

Kĩkũyũ

The Kĩkũyũ live on the southern and western sides of the mountain.[13][27] They are agriculturalists, and make use of the highly fertile volcanic soil on the lower slopes. The Kĩkũyũ people believe that their God, Ngai lived on Mount Kenya when he came down from the sky.[28] They believe that the mountain is Ngai's throne on earth. It is the place where Kĩkũyũ, the father of the tribe, used to meet with their God, Ngai.[28] They used to build their houses with the doors facing the mountain.[29] The Kĩkũyũ name for Mount Kenya is Kĩrĩ Nyaga (Kirinyaga), which literally translates to 'the shining mountain'. God's name in Kikuyu is also Mwene Nyaga meaning 'owner of the ostriches'. It can also be construed to mean ' possessor of light/brightness' in reference to the light reflected from the white glaciers on the mountain.

Embu

The Embu people live to the south-east of Mount Kenya,[13] and believe that the mountain is the home of their God, Ngai or Mwene Njeru. The mountain is sacred, and they build their houses with the doors facing towards it.[29] The Embu name for Mount Kenya is Kiri Njeru, which means mountain of whiteness.[29][21][22] The Embu people are closely related to the Mbeere people. They are the settlers of the windward side of the Mountain. This is a rocky semi dry area.

Maasai

The Maasai are semi-nomadic people, who use the land to the north of the mountain to graze their cattle. They believe that their ancestors came down from the mountain at the beginning of time.[29] The Maasai name for Mount Kenya is Ol Donyo Keri, which means 'mountain of stripes or many colours' depicting the snow, forest and other shades as observed from the surrounding plains.[30] At least one Maasai prayer refers to Mount Kenya:

God bless our children, let them be like the

olive tree of Morintat, let them grow and

expand, let them be like Ngong Hills like

Mt. Kenya, like Mt. Kilimanjaro and multiply in number.

— Collected by Francis Sakuda of Oloshoibor Peace Museum[30]

Ameru

The Ameru occupy the East and North of the Mountain. They are generally agricultural and also keep livestock and occupy what is among the most fertile land in Kenya. The Meru name for Mt. Kenya is Kirimara (That which has white stuff or snow).[31] Some Meru songs refer to Kirimara no makengi (The mountain is all speckles.) Other poem like songs imply that the mountain belongs to various sub-groups of the community. The Meru God Murungu was from the skies.

Other tribes

The first Europeans to visit Mount Kenya often brought members of other tribes as guides and porters. Many of these people had never experienced the cold, or seen snow and ice before. Their reactions were often fearful and suspicious.

Another trait of the Zanzibari character was shown at the same camp. In the morning the men came to tell me that the water they had left in the cooking-pots was all bewitched. They said it was white, and would not shake; the adventurous Fundi had even hit it with a stick, which would not go in. They begged me to look at it, and I told them to bring it to me. They declined, however, to touch it, and implored me to go to it. The water of course had frozen solid. I put one of the pots on the fire, and predicted that it would soon turn again into water. The men sat round and anxiously watched it; when it had melted they joyfully told me that the demon was expelled, and I told them they could now use this water; but as soon as my back was turned they poured it away, and refilled their pots from an adjoining brook.

— J W Gregory, The Great Rift Valley[9]

Mackinder's expedition of 1899 met some men from the Wadorobo tribe. They were at about 3,600 m (12,000 ft), and are an example of a tribe that use the mountain for normal purposes.[13]

Geology

Mount Kenya is a stratovolcano that was active in the Plio-Pleistocene. The original crater was probably over 6,000 m (20,000 ft) high; higher than Kilimanjaro. Since it became extinct there have been two major periods of glaciation, which are shown by two main rings of moraines below the glaciers. The lowest moraine is found at around 3,300 m (10,700 ft).[32] Today the glaciers reach no lower than 4,650 m (12,250 ft).[2] After studying the moraines, Gregory put forward the theory that at one time the whole summit of the mountain was covered with an ice cap, and it was this that eroded the peaks to how they are today.[6]

The lower slopes of the mountain have never been glaciated. They are now mainly cultivated and forested. They are distinguished by steep-sided V-shaped valleys with many tributaries. Higher up the mountain, in the area that is now moorland, the valleys become U-shaped and shallower with flatter bottoms. These were created by glaciation.[32]

When Mt Kenya was active there was some satellite activity. The north-eastern side of the mountain has many old volcanic plugs and craters. The largest of these, Ithanguni, even had its own ice cap when the main peaks were covered in ice. This can be seen by the smoothed summit of the peak. Circular hills with steep sides are also frequent in this area, which are probably the remains of small plugged vents. However, as the remaining mountain is roughly symmetrical, most of the activity must have occurred at the central plug.[32]

The rocks that form Mt Kenya are mainly basalts, rhomb porphyrites, phonolites, kenytes and trachytes.[32] Kenyte was first reported by Gregory in 1900 following his study of the geology of Mount Kenya.[33]

The geology of the Mount Kenya area was first considered by Joseph Thomson in 1883. He saw the mountain from the nearby Laikipia Plateau and wrote that it was an extinct volcano with the plug exposed.[20] However, as he had only seen the mountain from a distance his description was not widely believed, particularly after 1887 when Teleki and von Höhnel ascended the mountain and described what they considered to be the crater.[9] In 1893 Gregory's expedition reached the Lewis Glacier at 5,000 m (16,000 ft). He confirmed that the volcano was extinct and that there were glaciers present.[9][33] The first thorough survey was not undertaken until 1966.[32]

Peaks

The peaks of Mount Kenya are almost all from a volcanic origin. The majority of the peaks are located near the centre of the mountain. These peaks have an Alpine appearance due to their craggy nature. Typically of Alpine terrain, the highest peaks and gendarmes occur at the intersection of ridges.[4] The central peaks only have a few mosses, lichens and small alpine plants growing in rock crevices.[13] Further away from the central peaks, the volcanic plugs are covered in volcanic ash and soils.[34] The vegetation growing on these peaks is typical for the vegetation band they are in.

The highest peaks are Batian (5,199 m - 17,058 ft), Nelion (5,188 m - 17,022 ft) and Pt Lenana (4,985 m - 16,355 ft). Batian and Nelion are only 250m apart but separated by the Gates of Mist gap, which is equally deep.[2] Coryndon Peak (4,960 m - 16,355 ft) is the next highest, but unlike the previous peaks it does not form a part of the central plug.[4]

Other peaks around the central plug include Pt Piggot (4,957 m - 16,266 ft), Pt Dutton (4885 m - 16,027 ft), Pt John (4883 m - 16,016 ft), Pt John Minor (4875 m - 15,990 ft), Krapf Rognon (4800 m - 15,740 ft), Pt Peter (4757 m - 15,607 ft), Pt Slade (4750 m - 15,580 ft) and Midget Peak (4700 m - 15,420 ft). All of these have a steep pyramidal form.[2][4]

Significant craggy outlying peaks include Terere (4714 m - 15,462 ft) and Sendeyo (4704 m - 15,433 ft) which form a pair of twin peaks to the north of the main plug. Together, they form a large parasitic plug. Other notable peaks include The Hat (4639 m - 15,220 ft), Delamere Peak, Macmillan Peak and Rotundu.[2]

-

Batian on the left, Nelion on the right, and Slade in the foreground

-

Lenana, the third highest peak, is the most ascended.

-

Krapf Rognon (4.800 m) and Krapf glacier

-

Midget peak can be climbed in a day.[21]

-

Terere and Sendeyo are two craggy outlying peaks

-

Mugi hill and the Giant's Billards Table offers some of the best hillwalking in Kenya.[29]

Glaciers

The glaciers on Mount Kenya are retreating rapidly. The Mountain Club of Kenya in Nairobi has photographs showing the mountain when it was first climbed in 1899, and again more recently, and the retreat of the glaciers is very evident.[35][36] Descriptions of ascents of several of the peaks advise on the use of crampons, but now there is no ice to be found. There is no new snow to be found, even on the Lewis Glacier (the largest of them) in winter, so no new ice will be formed. It is predicted to be less than 30 years before there will no longer be ice on Mount Kenya.[29]

The glacier names are (clockwise from the north):

- Northey, Krapf, Gregory, Lewis, Diamond, Darwin, Forel, Heim, Tyndall, Cesar, Josef.

The area of glaciers on the mountain was measured in the 1980s, and recorded as about 0.7 km² (0.25 square miles).[37] This is far smaller than the first observations, made in the 1890s.

Periglacial landforms

Although Mount Kenya is on the equator the freezing nightly temperatures result in periglacial landforms. There is permafrost a few centimetres (inches) below the surface. Patterned ground is present at 3,400 metres (11,155 ft) to the west of Mugi Hill.[4][2] These mounds grow because of the repeated freezing and thawing of the ground drawing in more water. There are blockfields present around 4,000 metres (13,123 ft) where the ground has cracked to form hexagons. Solifluction occurs when the night temperatures freeze the soil before it thaws again in the morning. This daily expansion and contraction of the soil prevents the establishment of vegetation.[21]

Rivers

Mount Kenya is the main water catchment area for two large rivers in Kenya; the Tana, the largest river in Kenya, and the Ewaso Ng'iso North.[7] The Mount Kenya ecosystem provides water directly for over 2 million people.[7] The rivers on Mount Kenya have been named after the villages on the slopes of the mountain that they flow close to. The Thuchi River is the district boundary between Meru and Embu. Mount Kenya is a major water tower for the Tana river which in 1988 supplied 80% of Kenya's electricity using a series of seven hydroelectric powerstations and dams.[38]

The density of streams is very high, especially on the lower slopes which have never been glaciated. The ice cap which used to cover the mountain the the Pliocene eroded large U-shaped valleys which tend to only have one large stream.[4] Where the original shape of the shield volcano is still preserved, there have been millions of years for streams to erode the hillside. This area is therefore characterised by frequent deep fluvial V-shaped valleys.[39] The gradual transition from glaciated to fluvial valley can be clearly observed.[40]

Rivers which start on Mount Kenya are the tributaries of two large Kenyan rivers: the Tana and the Ewaso Ng'iro rivers. A lot of Mount Kenyan rivers flow into the Sagana which itself is a tributary of the Tana, which it joins at the Masinga Reservoir. The rivers in the northern part of the mountain, such as the Burguret, Naro Moro, Nanyuki, Liki, Sirimon flow into the Ewaso Ng'iro. The rivers to the south-west, such as the Keringa and Nairobi flow into the Sagana and then into the Tana. The remaining rivers to the south and east, such as the Mutonga, Nithi, Thuchi and Nyamindi, flow directly into the Tana.[39][40]

Ecology

Mount Kenya has several distinct ecological zones, between the savanna surrounding the mountain to the nival zone by the glaciers. Each zone has a dominant species of vegetation. Many of the species found higher up the mountain are endemic, either to Mount Kenya or East Africa, and are highly specialised.[13]

There are also differences within the zones, depending on the side of the mountain and aspect of the slope. The south-east is much wetter than the north,[37] so species more dependent on moisture are able to grow. Some species, such as bamboo, are limited to certain aspects of the mountain because of the amount of moisture.[2]

Zones

The climate of Mount Kenya changes considerably with altitude. Around the base of the mountain is fertile farmland. The tribes living around the mountain have cultivated this cool relatively moist area for centuries[41].

Mount Kenya is surrounded by forests. The vegetation in the forests depend on rainfall, and the species present differ greatly between the northern and southern slopes.[8] As time has passed the trees on the edge of the forest have been logged and the farmland has encroached further up the fertile slopes of the mountain.[41]

Above the forest is a belt of bamboo. This zone is almost continuous, but is unable to grow in the north because there is not enough rainfall. The bamboo is entirely natural,[21] and prevents many animals from living further up the mountain. Tracks are common through the bamboo. They are made by large animals such as elephants and buffalo when they fight their ways higher. They do not spend long within the bamboo, as it is all inedible except for tender new shoots. Bamboo suppresses other vegetation, so it is uncommon to find trees or other plants here.[2]

Above the bamboo is the timberline forest. The trees here are often smaller than the trees in the forests lower down the mountain.[42]

When the trees can no longer grow the vegetation changes into heathland and chaparral. Heathland is found in the wetter areas, on the west side of Mount Kenya, and is dominated by giant heathers. Chaparral is found in the drier areas and grasses are more common.[21] The ground here is often waterlogged, but bush fires are still frequent.[41]

As the altitude increases the temperature fluctuations become extreme and the air becomes thinner and drier. This region is known as the Afro-alpine zone. The environment here is very isolated, with the only similar area nearby being the Aberdares, which are 80 km (50 miles) away[13]. Many of the species here are endemic, with adaptations to the cold and fluctuating temperatures.[43] Typical plants here include giant groundsels (senecios) and giant lobelias.[13]

The region where the glaciers have recently retreated from is nival zone. It is the area that plants have not yet been able to colonise. On Mount Kenya this zone is not continuous as the glaciers are no longer continuous.[13]

Flora

The flora found on Mount Kenya varies with altitude, aspect and exposure, but very little with seasons.[44] Lower down the mountain the air contains more moisture and oxygen, and the temperature is warm all year. As the altitude increases, the plants have to be more specialised, with adaptations to strong sunlight, little oxygen and freezing night temperatures.[21][42]

Plants in the Afro-alpine zone have overcome these difficulties in several ways. One adaptation is known as the giant rosette, which is exhibited by giant senecio, lobelia and giant thistle (Carduus). These plants have specialist ways of retaining water in the dry air, as well as preventing the water freezing overnight.[43] They also use dead leaves or hairs to protect their buds from freezing. Another adaptation is to flower simultaneously. Plants in cold temperatures do not grow fast, so it is impossible to flower every year. By synchronising their flowering they increase their chances of pollination.[45]

Many plants in the Afro-alpine zone of Mount Kenya tend to be large. This is an adaptation against the cold. However, nearer the nival zone the plants decrease in size again, as there are not enough resources, including warmth, to allow them to grow any larger[13].

Fauna

The majority of animals live lower down on the slopes of Mount Kenya. Here there is more vegetation and the climate is less extreme. Various species of monkeys, several antelopes, tree hyrax, porcupines and some larger animals such as elephant and buffalo all live in the forest.[2] Predators found here include hyena and leopard, and occasionally lion[2].

No animals live permanently in the bamboo zone, although several cross it to access the higher zones of the mountain.[13]

There are few mammals found at high altitudes on Mount Kenya. The Mount Kenya hyrax and common duiker are able to live here, and are very important to the ecosystem. Some smaller mammals, such as the groove-toothed rat, can live here by burrowing into the giant senecios and using their thick stem of dead leaves as insulation.[13] A few larger mammals occasionally visit these altitudes. Leopard skeletons are sometimes found at altitude, and other sightings are remembered in names such as Simba Tarn (simba means lion in Swahili).[21] However, there is not enough prey to allow these animals to live here permanently.

Birds are more common than mammals in the Afro-alpine zone, with many species of sunbirds, alpine chats and starlings resident here as well as some of their predators; the auger buzzard, lammergeier and Verreaux eagle. Birds are important in this ecosystem as they pollinate many plants[44].

Climate

The climate of Mount Kenya has played a critical role in the development of the mountain, influencing the topography and ecology amongst other factors. It has a typical equatorial mountain climate which Hedberg described as winter every night and summer every day.[46] Mount Kenya is home to one of the Global Atmosphere Watch's atmospheric monitoring stations.[47]

Seasons

The year is divided into two distinct wet seasons and two distinct dry seasons which mirror the wet and dry seasons in the Kenyan lowlands.[49] As Mount Kenya ranges in height from 1,374m to 5,199m the climate varies considerably over the mountain and has different zones of influence. The lower, south eastern slopes are the wettest as the predominant weather system comes from the Indian ocean. This leads to very dense montane forest on these slopes. High on the mountain most of the precipitation falls as snow, but the most important water source is frost.[50] Combined, these water sources feed 10 glaciers.

The current climate on Mount Kenya is wet, but drier than it has been in the past. The temperatures span a wide range, which diminishes with altitude. In the lower alpine zone they usually do not go below -12°C.[51] Snow and rain are common from March to December, but especially in the two wet seasons. The wet seasons combined account for 5/6 of the annual precipitation. The monsoon, which controls the wet and dry seasons, means that most of the year there are south-easterly winds, but during January and February the dominate wind direction is north-easterly.

Mount Kenya, like most locations in the tropics, has two wet seasons and two dry seasons as a result of the monsoon. From mid-March to June the heavy rain season, known as the long rains, brings approximately half of the annual rainfall on the mountain.[41] This is followed by the wetter of the two dry seasons which lasts until September. October to December are the short rains when the mountain receives approximately a third of its rainfall total. Finally from December to mid-March is the dry, dry season when the mountain experiences the least rain.

Mount Kenya straddles the equator. This means during the northern hemisphere summer the sun is to the north of the mountain. The altitude and aspect of the watersheds and main peaks results in the north side of the upper mountain being in summer condition. Simultaneously, the southern side is experiencing winter conditions. Once it is the southern hemisphere summer, the situation reverses.[21]

Daily pattern

During the dry season the mountain almost always follows the same daily weather pattern. Large daily temperature fluctuations occur which led Hedberg to exclaim winter every night and summer every day.[46] There is variation in minimum and maximum temperatures day to day, but the standard deviation of the mean hourly pattern is small.

A typical day is clear and cool in the morning with low humidity. The mountain is in direct sunlight which causes the temperatures to rise quickly with the warmest temperatures occurring between 9 and 12am. This corresponds to a maxima in the pressure, usually around 10am. Low on the mountain, between 2,400 and 3,000m, clouds begin to form over the western forest zone, due to moist air from Lake Victoria.[52] The anabatic winds caused by warm rising air gradually bring these clouds to the summit region in the afternoon. Around 3pm there is a minimum in sunlight and a maximum in humidity causing the actual and perceived temperature to drop. At 4pm there is a minimum in the pressure. This daily cover of cloud protects the glaciers on the south-west of the mountain which would otherwise get direct sun every day, enhancing their melt.[53] The upwelling cloud eventually reaches the dry easterly air streams and dissipates, leading to a clear sky by 5pm. There is another maxima of temperature associated with this.

Being an equatorial mountain the day light hours are constant with twelve hour days. Sunrise is about 0530 with the sun setting at 1730. Over the course of the year there is a one minute difference between the shortest and longest days.[54] At night, the sky is usually clear with katabatic winds blowing down the valleys. Above the lower alpine zone there is usually frost every night.[51]

Walking routes

There are eight walking routes up to the main peaks. Starting clockwise from the north these are the: Meru, Chogoria, Kamweti, Naro Moru, Burguret, Sirimon and Timau Routes.[2] Of these Chogoria, Naro Moru and Sirimon and used most frequently and therefore have staffed gates. The other routes require special permission from the Kenya Wildlife Service to use.[29][55]

Meru Route

This route leads from Katheri, south of Meru, to Lake Rotundu following the Kathita Munyi river. It does not lead to the peaks, but up onto the alpine moorland on the slopes of the mountain.[2]

Chogoria Route

This route leads from Chogoria town up to the peaks circuit. The 32 km (20 miles) from the forest gate to the park gate are often done by vehicle, but it is also possible to walk.[21] There is much wildlife in the forest, with safari ant columns crossing the track, monkeys in the trees, and the potential for seeing elephant, buffalo and leopard.[56] The road is not in good condition, and requires careful driving and walking. Near the park gate the bamboo zone starts, with grasses growing to 12 m high (40 ft).[29]

Once in the park the track passes through rosewood forests, with lichens hanging from the branches. At one point the path splits, with the smaller track leading to a path up the nearby Mugi Hill and across to Lake Ellis.[2]

Near the trackhead a small bridge crosses the Nithi stream. (Following the stream down-river a few hundred metres leads to The Gates Waterfall.) The path heads up a ridge above the Gorges Valley, with views to the peaks, Lake Michaelson, The Temple, and across the valley to Delamere and Macmillan Peaks. Hall Tarns are situated right on the path and above a 200 m (700 ft) cliff directly above Lake Michaelson.[21]

As the path carries on it crosses the flat head of the Nithi River and then the slope steepens. The path splits, heading west to Simba Col, and south west to Square Tarn. These are both on the Peak Circuit Route. [55] [57]

Kamweti Route

This is the longest route in to the peaks and follows the Nyamindi West River.[2] It is a restricted route,[29] but is still used occasionally.[58]

Naro Moru Route

This route is taken by many of the trekkers who try to reach Point Lenana. It can be ascended in only 3 days and has bunkhouses at each camp so a tent is not necessary.[29][22] The terrain is usually good, although one section is called the Vertical Bog.[21]

The track starts in Naro Moru town and heads past the Park Headquarters up the ridge between the Northern and Southern Naro Moru Rivers. At the roadhead is the Meteorological Station, to which it is possible to drive in the dry season. The route drops down into the Northern Naro Moru Valley to Mackinder's Camp on the Peak Circuit Path. [55]

Burguret Route

This route has restricted access.[29] It starts in Gathiuru, and mainly follows the North Burguret River, then continues up to Hut Tarn on the Peak Circuit Path.

Sirimon Route

This route starts 15 km (9 miles) east around the Mount Kenya Ring Road from Nanyuki. The gate is 10 km (6 miles) further along the track, which can be walked or driven by two-wheel drives.[21]

The track climbs up through the forest. On the north side of the mountain there is no bamboo zone, so the forest gradually turns into moorland covered with giant heather.[59] The track ends at Old Moses Hut and becomes a path. This continues up the hill before splitting into two routes. To the left, the least used path goes around the side of the Barrow, to Liki North Hut.[2] The vegetation becomes more sparse, with giant lobelia and groundsels dotted around. The path climbs over a ridge, before rejoining the main path ascending the Mackinder Valley. Shipton's Cave can be found in the rock wall to the left of the steep path just before reaching Shipton's Camp.[21]

From Shipton's Camp, it is possible to ascend the ridge directly in front of the camp to the site of Kami Hut, which no longer exists, or follow the river up to Lower Simba Tarn and eventually to Simba Col. These are both on the Peak Circuit Path.[55]

Timau Route

This is a restricted route.[29] It starts very close to the Sirimon Route, at Timau Village, and skirts around the edge of the forest for a considerable distance. It used to lead to the highest point on the mountain to which is was possible to drive, but has not been used for many years. From the trackhead it is possible to reach Halls Tarns in a few hours, then follow the Chogoria Route to the Peak Circuit Path.[2]

Peak Circuit Path

This is a path around the main peaks, with a distance of about 10 km (6 miles) and height gain and loss of over 2000 m (6,600 ft). It can be walked in one day, but more commonly takes two or three. It can also be used to join different ascent and descent routes. The route does not require technical climbing.[22] [55]

Climbing routes

Most of the peaks on Mount Kenya have been summited. The majority of these involve rock climbing as the easiest route. The grades given are UIAA alpine climbing grades. [60]

| Peak | Altitude | Route Name | Grade | Climbing Season* | First Ascent |

| Batian | 5,199 m (17,058 ft) | North Face Standard Route | IV+ | Summer | A.H. Firmin and P. Hicks, 31 July 1944[61] [62] |

| South-West Ridge Route | IV | Winter | A.H. Firmin and J.W. Howard, 8 January 1946[62] [63] | ||

| Nelion | 5,188 m (17,022 ft) | Normal Route | IV- | Summer/Winter | E.E. Shipton and P.W. Harris 6 January 1929[62] [64] |

| Batian/Nelion | Ice Window Route | V- | Summer | P. Snyder, Y. Laulan and B. LeDain 20 August 1974[62] [65] | |

| Diamond Couloir | VI | Summer | P. Snyder and T. Mathenge 4-5 October 1973[62] [65] | ||

| Pt Pigott | 4957 m (16,266 ft) | South Ridge | III+ | Summer/Winter | W.M. and R.J.H. Chambers February 1959[21] |

| Thomson's Flake | 4947 m (16,230 ft) | Thomson's Flake | VI | Summer/Winter | L. Herncarek, W. Welsch and B. Cliff 9 September 1962[66] |

| Pt Dutton | 4885 m (16,027 ft) | North-East Face and Ridge | IV | Summer/Winter | S. Barusso and R.D. Metcalf 4 August 1966[21] [62] |

| Pt John | 4883 m (16,016 ft) | South-East Gully | III | Summer | E.E. Shipton and R.E.G. Russel 18 December 1929[21] [62] |

| Pt Melhuish | 4880 m (16,010 ft) | South-East Face | IV+ | Summer/Winter | R.M.Kamke and W.M. Boyes December 1960[21] [62] |

| Pt Peter [62] | 4757 m (15,607 ft) | North-East Gully and Ridge | III | Summer/Winter | E.E. Shipton and H.W. Tilman July 1960[21] |

| Window Ridge | VI, A1 | Summer/Winter | F.A. Wedgewood and H.G. Nicol 8 August 1963[21] | ||

| Midget Peak | 4700 m (15,420 ft) | South Gully | IV | Summer/Winter | E.E. Shipton and H.W. Tilman August 1930[22] |

* Climbing Season refers to northern hemisphere summers and winters.

Huts

Caretakers are present at most huts,[29] but not all. The huts range from very basic (Liki North) with little more than a roof, to luxurious with log fires and running water (Meru Mt Kenya Lodge). Most huts have no heat or light, but are spacious with dormitories and communal areas. They also offer separate accommodation for porters and guides. The communal areas of the huts can be used by campers wishing to retreat from the weather or to store food away from the hyaena and hyraxes.

Around the Peak Circuit Path

- Austrian Hut/Top Hut (4790 m - 15,715 ft)

- Austrian Hut is the highest hut on Mount Kenya, with the exception of Howell Hut on Nelion. It is a good base for the ascent of Lenana, or for exploring the surrounding area. Peaks that can be ascended with Austrian Hut as a base camp include Point Thompson, Point Melhuish and Point John. It is also the starting point for the Normal Route up Nelion, as well as other routes up to the summits.[21]

- The hut was built with Austrian funding, following the rescue of Gerd Judmeier.[67]

- Two Tarn Hut (4490 m - 14,731 ft)

- Two Tarn Hut is located on Two Tarn Col beside a lake. It is often used before ascending Batian from the southern and western routes.[21]

- Kami Hut (site of) (4439 m - 14,564 ft)

Huts on Chogoria Route

- Meru Mt Kenya Lodge (3017 m - 9,898 ft)

- This is a privately owned lodge on the edge of the national park. Park fees have to be paid. The lodge is about 500 m from the park gate, and consists of several log cabins, each with a bedroom, kitchen, bathroom and living area with log fireplace. There is hot running water in the cabins, which sleep 3-4 people. The campsite is located at the park gate, and has running water.[29]

- Urumandi Hut (site of) (3063 m - 10,050 ft)

- This hut was built in 1923 and is no longer used.[21]

- Minto's Hut (porters only) (4290 m- 14,075 ft)

- Minto's Hut sleeps 8 porters, and is situated near Hall Tarns. There is a campsite nearby. Water is taken directly from the tarns. The tarns have no outflow and so the stagnant water needs to be filtered or boiled before use.[21]

Huts on Naro Moru Route

- The Warden's Cottage (2400 m - 7,900 ft)

- This was home to the park's senior wardens until 1998.[29] There are two bedrooms, a bathroom, a kitchen and a living area with veranda and log fire. There is running hot water. The cottage is inside the national park, so park fees must be paid.

- Meteorological Station (3050 m - 10,000 ft)

- The Met Station is administered by Naro Moru Lodge.[29] There are several bunkhouses here as well as a campsite.

- Mackinder's Camp (4200 m -13,778 ft)

- Mackinder's Camp is also administered by Naro Moru Lodge.[29] There is a large bunkhouse and plenty of space for camping.

Huts on Sirimon Route

- Sirimon Bandas (2650 m - 8,690 ft)

- Sirimon Bandas are located at Sirimon Gate, just inside Mt Kenya National Park. The bandas each have two bedrooms, a kitchen, a dining room, a bathroom and a veranda. There is hot running water. The surrounding area contains much wildlife, including hyaena, zebra, many antelope, baboons and lots of species of birds. Park fees have to be paid, although the bandas are situated just outside the gates.

- There is a campsite next to the bandas, with running water and long drops.[29]

- Old Moses Camp (3400 m - 11,150 ft)

- Old Moses Camp is administered by Mountain Rock Bantu Lodge.[68] It has dormitories and a large campsite, as well as accommodation for guides and porters.

- Liki North Hut (3993 m - 13,095 ft)

- Liki North Hut is little more than a shed to keep the weather off. There is space to camp and a river nearby for water. The hut can sleep 8 people. It is on the lesser used path between Old Moses and Shipton's Camps and can by used as a base for climbing Terere and Sendeyo or to stop off on the way to Shipton's Camp.[21]

- Shipton's Camp (4236 m - 13,894 ft)

- Shipton's Camp is administered by Mountain Rock Bantu Lodge.[68] It is home to many rock hyrax, as well as striped mice, many types of sunbirds and Alpine Chats. Mountain Buzzards fly overhead. The vegetation is dominated by giant groundsel, but there are many flowers and lobelia as well. On the skyline is a view of Points Peter and Dutton, with Batian overshadowing them. Also in view are Thompson's Flake and Point Thompson, with Point Lenana on the other side of the Gregory Glacier. In front of the main peaks is the Krapf Rognon, with the Krapf Glacier behind.

Huts on Nelion

- Howell Hut (5188 m - 17,023 ft)

- This hut, on top of Nelion, was built by Ian Howell in February 1970. The corrugated iron for the hut was dropped onto the Lewis Glacier by helicopter; Howell then carried it to the summit in thirteen solo ascents and built the hut.[21]

Other huts around the mountain

- Mountain Rock Bantu Lodge

- The lodge is situated north of Naro Moru and offers rooms, tented accommodation and a campsite. It administers the Old Moses and Shipton's Camps on the Sirimon Route.[68]

- Naro Moru River Lodge

- This lodge is situated near Naro Moru, and offers facilities from bird watching to equipment hire and guided climbs of the mountain. It also administers the bunkhouses at the Met Station and Mackinder's Camp on the Naro Moru Route.[29]

- The Serena Mountain Lodge

- This luxury hotel is found on the western slopes of the mountain, at around 2,200 m (6,600 ft). It has its own waterhole and offers guided walks, trout fishing and luxury climbs up the mountain, as well as conference facilities.[69]

- Naro Moru Youth Hostel

- The youth hostel is situated between Naro Moru and Naro Moru Gate, and is a renovated farmhouse. It has dormitories and a campsite, with hot water, a kitchen and equipment hire.[29]

- Castle Forest Lodge

- This lodge was built by the British in the late 1920s as a retreat for royalty.[29] It is on the southern slopes of the mountain in the forest at about 2,100 m (6,900 ft).

- Rutundu Log Cabins

- This luxurious lodge is on the northern slopes of the mountain at about 3,100 m (10,200 ft).[29]

Etymology

Mount Kenya received its current name by Krapf who sighted it in 1849 although the spelling has changed from Kenia to Kenya. It is unclear what native word of which tribe Krapf recorded. Various tribes have different names for the mountain. The Kĩkũyũ call it Kirinyaga, which means "white or bright mountain". The Embu call it Kirenia, or "mountain of whiteness". The Maasai call it Ol Donyo Eibor or Ol Donyo Egere, which mean "the White mountain" or "the speckled mountain" respectively.[20] The Wakamba call it Kiinyaa, or "the mountain of the ostrich". The male ostrich has speckled tail feathers, which look similar to the speckled rock and ice on the mountain.[22][29]

Krapf was staying in a Wakamba village when he first saw the mountain.[70] Krapf, however, recorded the name as both Kenia and Kegnia.[18][70] According to some sources, this is a corruption of the Wakamba Kiinyaa.[71] Others however say that this was on the contrary a very precise notation of a native word pronounced ˈkenia. [72] Nevertheless, the name was usually Template:PronEng in English.[73]

It is important to note that at the time this referred to the mountain without having to include mountain in the name. The current name Mount Kenya was used by some as early as 1894,[6] but this was not a regular occurrence until 1920 when Kenya Colony was established.[74] Before 1920 the area now known as Kenya was known as the British East Africa Protectorate and so there was no need to mention mount when referring to the mountain.[74] Mount Kenya was not the only English name for the mountain as shown in Dutton's 1929 book Kenya Mountain.[8] By the 1930s Kenya was becoming the dominant spelling, but Kenia was occasionally used.[75] At this time both were still pronounced ˈkiːnjə in English.[71]

Kenya achieved independence in 1963, and Jomo Kenyatta was elected as the first president.[41] He had previously assumed this name to reflect his commitment to freeing his country and his pronunciation of his name resulted in the pronunciation of Kenya in English changing back to an approximation of the original native pronunciation, the current ˈkɛnjə.[71] So the country was named after the colony, which in turn was named after the mountain as it is a very significant landmark.[74][76] To distinguish easily between the country and the mountain, the mountain became known as Mount Kenya with the current pronunciation ˈkɛnjə.[73]

Names of peaks

The peaks of Mount Kenya have been given names from three different sources. Firstly, several Maasai chieftains have been commemorated, with names such as Batian, Nelion and Lenana. These names were suggested by Mackinder, on the suggestion of Hinde, who was the resident officer in Maasailand at the time of Mackinder's expedition. They commemorate Mbatian, a Maasai Laibon (Medicine Man), Nelieng, his brother, and Lenana and Sendeyo, his sons.[8] Terere is named after another Maasai headman.

The second type of names that were given to peaks are after climbers and explorers. Some examples of this are Shipton, Sommerfelt, Tilman, Dutton and Arthur. Shipton made the first ascent of Nelion, and Sommerfelt accompanied Shipton on the second ascent. Tilman made many first ascents of peaks with Shipton in 1930. Dutton and Arthur explored the mountain between 1910 and 1930. Arthur Firmin, who made many first ascents, has been remembered in Firmin's Col. Humphrey Slade, of Pt Slade, explored the moorland areas of the mountain in the 1930s, and possibly made the first ascent of Sendeyo.[21]

The remaining names are after well-known Kenyan personalities, with the exception of John and Peter, which were named by the missionary Arthur after two disciples. Pigott was the Acting Administrator of Imperial British East Africa at the time of Gregory's expedition, and there is a group of four peaks to the east of the main peaks named after governors of Kenya and early settlers; Coryndon, Grigg, Delamere and McMillan.[21]

The majority of the names were given by Melhuish and Dutton, with the exception of the Maasai names and Peter and John. Interestingly Pt Thomson is not named after Joseph Thomson, who confirmed the mountain's existence, but after another J Thomson who was an official Royal Geographical Society photographer.[21]

Books about Mount Kenya

- Sir Halford Mackinder, The First Ascent of Mount Kenya [K. M. Barbour, ed.], (London 1991); the story of the first ascent of Batian, including Mackinder's diary and some of the expedition's photographs. Barbour discusses reasons why Mackinder, who wrote and published other books, did not publish a detailed account of the expedition.[77]

- E. A. T. Dutton, Kenya Mountain (London 1929); the account of an expedition to Mount Kenya in 1926; illustrated.[8]

- Vivienne de Watteville, Speak to the Earth - Wanderings and Reflections among Elephants and Mountains (London & New York, 1935); account of the author's sojourn in a small hut in the region of the Ellis Lake and her explorations of the Gorges Valley; illustrated.[78]

- H. W. Tilman, Snow on the Equator (London 1937); account of the first ascent (with Shipton) of the NW ridge and Nelion; illustrated.[79]

- Eric Shipton, Upon that Mountain, (London 1943); account of the first ascent (with Tilman) of the NW ridge and Nelion; illustrated.[80]

- Felice Benuzzi, Fuga sul Kenya (Milan 1947) / No Picnic on Mount Kenya (London 1952); a mountaineering classic, about three Prisoners of War who escape from their prison camp in 1943, ascend the mountain with sparse rations, improvised equipment and no maps, and then break back into to their prison camp.[23]

- Roland Truffaut, Du Kenya au Kilimanjaro (Paris 1953) / From Kenya to Kilimanjaro (London 1957); account of the 1952 French ascent of the N. face of Mt Kenya; illustrated.[81]

- I.Allan, Guide to Mount Kenya (1981; 1991; many updates); authoritative guide to the routes on the peaks.[21]

- Hamish MacInnes, The Price of Adventure, (London 1987); includes the story of the week-long rescue of Gerd Judmeier after his fall near the summit of Batian in the early 1970s.[67]

- I.Allan, C. Ward, G. Boy, Snowcaps on the Equator (London 1989); a history of the East African mountains and their ascents, including the more recently pioneered routes; illustrated.[82]

- John Reader, Mount Kenya (London 1989); account of an ascent of Nelion, with Iain Allan as guide; illustrated. [83]

- M. Amin, D. Willetts, B. Tetley, On God's Mountain: The Story of Mount Kenya (London 1991). A photographic celebration of the mountain. [84]

- Kirinyaga, Mike Resnick, (1989). [12]

- Facing Mount Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta, (1938); a book about the Kĩkũyũ.[28]

See also

References

- ^ Mount Kenya Map Sample

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Mount Kenya Map and Guide (Map) (4th ed.). 1:50,000 with 1:25,000 inset. EWP Map Guides. Cartography by EWP. EWP. 2007. ISBN 9780906227961.

- ^ a b c d Rough Guide Map Kenya (Map) (9 ed.). 1:900,000. Rough Guide Map. Cartography by World Mapping Project. Rough Guide. 2006. ISBN 1-84353-359-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Baker, B. H. (1967). Geology of the Mount Kenya area. Nairobi: Geological Survey of Kenya.

- ^ Philippe Nonnotte. "Étude volcano-tectonique de la zone de divergence Nord-Tanzanienne (terminaison sud du rift kenyan) - Caractérisation pétrologique et géochimique du volcanisme récent (8 Ma – Actuel) et du manteau source - Contraintes de mise en place thèse de doctorat de l'université de Bretagne occidentale, spécialité : géosciences marines" (PDF).

- ^ a b c Gregory, J. W. (1894). "Contributions to the Geology of British East Africa.-Part I. The Glacial Geology of Mount Kenya". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 50: 515–530. Cite error: The named reference "gregory1894" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f Gichuki, Francis Ndegwa (1999). "Threats and Opportunities for Mountain Area Development in Kenya" (subscription required). Ambio. 28 (5). Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences: 430–435.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "development" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g Dutton, E.A.T. (1929). Kenya Mountain. London: Jonathan Cape.

- ^ a b c d e

Gregory, John Walter (1968). The Great Rift Valley. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b von Höhnel, Lieutenant Ludwig (1894). Discovery of Lakes Rudolf and Stefanie. London: Longmans.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Mackinder, Halford John (1900). "A Journey to the Summit of Mount Kenya, British East Africa". The Geographical Journal. 15 (5): 453–476. doi:10.2307/1774261. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Resnick, Mike (1998). Kirinyaga: a fable of Utopia. Ballantine. p. 293. ISBN 0345417011.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Coe, Malcolm James (1967). The Ecology of the Alpine Zone of Mount Kenya. The Hague: Dr W. Junk.

- ^ "World Heritage Nomination - IUCN Technical Evaluation Mount Kenya (Kenya)" (PDF).

- ^ a b c United Nations (2008). "Mount Kenya National Park/Natural Forest". Archived from the original on 2006-12-30. Retrieved 2008-02-23. Cite error: The named reference "unesco" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Kenya Wildlife Service (2007). "Mount Kenya National Park". Archived from the original on 2007-06-22. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme (1998). "Protected Areas and World Heritage". Archived from the original on 2007-02-12. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ a b c d Krapf, Johann Ludwig (1860). Travels, Researches, and Missionary Labours in Eastern Africa. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- ^ Krapf, Johann Ludwig (13 May 1850). "Extract from Krapf's diary". Church Missionary Intelligencer. i: 345.

- ^ a b c Thomson, Joseph (1968). Through Masai Land (3 ed.). London: Frank Cass & Co Ltd.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al Allan, Iain (1981). The Mountain Club of Kenya Guide to Mount Kenya and Kilimanjaro. Nairobi: Mountain Club of Kenya. ISBN 978-9966985606.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Burns, Cameron (1998). Kilimanjaro & Mount Kenya; A Climbing and Trekking Guide. Leicester: Cordee. ISBN 1-871890-98-5.

- ^ a b Benuzzi, Felice (2005). No Picnic on Mount Kenya: A Daring Escape, a Perilous Climb. The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1592287246.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Charter aircraft crashes into Kenya's Mount Kenya., Airline Industry Information, 21 July 2003

- ^ Rescue teams resume efforts to recover bodies of those killed in charter aircraft crash, Airline Industry Information, 23 July 2003

- ^ "Aircraft flown off Mount Kenya". News. The Times. No. 49451. London. January 23 1943. col C, p. 3.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) template uses deprecated parameter(s) (help) - ^ Richards, Charles (1960). East African Explorers. London: Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Kenyatta, Jomo (1961). Facing Mount Kenya. London: Secker and Warburg.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w

Kenya Wildlife Service (2006), Mount Kenya Official Guidebook, Kenya Wildlife Service

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Somjee, Sultan (2000). "Oral Traditions and Material Culture: An East Africa Experience". Research in African Literatures. 31 (4): 97–103. doi:10.2979/RAL.2000.31.4.97. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ^ Fadiman, Jeffrey A. (1994). When We Began There Were Witchmen. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08615-5. Retrieved 14/5/09.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e Baker, B. H. (1967). Geology of the Mount Kenya Area. Geological Survey of Kenya. Ministry of Natural Resources.

- ^ a b Gregory, J. W. (1900). "Contributions to the Geology of British East Africa.-Part II. The Geology of Mount Kenya". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 56: 205–222.

- ^ Speck, Heinrich (1982). "Soils of the Mount Kenya Area: Their formation, ecology, and agricultural significance". Mountain Research and Development. 2 (2): 201–221. doi:10.2307/3672965. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Mountain Club. "Mountain Club of Kenya Homepage". Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ Recession of Equatorial Glaciers. A Photo Documentation, Hastenrath, S., 2008, Sundog Publishing, Madison, WI, ISBN-13: 978-0-9729033-3-2, 144 pp.

- ^ a b

Karlén, Wibjörn (1999). "Glacier Fluctuations on Mount Kenya since ~6000 Cal. Years BP: Implications for Holocene Climate Change in Africa". Ambio. 28 (5). Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences: 409–418.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ojany, Francis F. (1993). "Mount Kenya and its environs: A review of the interaction between mountain and people in an equatorial setting". Mount Research and Development. 13 (3). International Mountain Society and United Nations University: 305–309. doi:10.2307/3673659.

- ^ a b Geological Map of the Mount Kenya Area (Map) (1st ed.). 1:125000. Geological Survey of Kenya. Cartography by B. H. Baker, Geological Survey of Kenya. Edward Stanford Ltd. 1966.

{{cite map}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=and|accessmonth=(help) - ^ a b Mt Kenya 1:50000 Map and Guide (Map) (1 ed.). 1:50000 with 1:25000 inset. Cartography by West Col Productions. Andrew Wielochowski and Mark Savage. 1991. ISBN 0-906227-39-9.

- ^ a b c d e Castro, Alfonso Peter (1995). Facing Kirinyaga. London: Intermediate Technology Publications Ltd. ISBN 1-85339-253-7. Cite error: The named reference "castro" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b

Niemelä, Tuomo (2004). "Zonation and characteristics of the vegetation of Mt. Kenya". Expedition reports of the Department of Geography, University of Helsinki. 40: 14–20. ISBN 952-10-2077-6.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Beck, Erwin (1984). "Equilibrium freezing of leaf water and extracellular ice formation in Afroalpine 'giant rosette' plants". Planta. 162: 276–282. doi:10.1007/BF00397450.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Smith, Alan P. (1987). "Tropical Alpine Plant Ecology". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 18: 137–158. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.001033.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Young, Truman P. (1992). "Giant senecios and alpine vegetation of Mount Kenya". Journal of Ecology. 80: 141–148.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hedberg, O. (1969). "Evolution and speciation in a tropical high mountain flora". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 1: 135–148. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1969.tb01816.x.

- ^ Henne, Stephan (November 2008). "Mount Kenya Global Atmosphere Watch Station (MKN): Installation and Meteorological Characterization". Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. 47 (11): 2946–2962.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Camberlin, P (2003). "The onset and cessation of the "long rains" in eastern Africa and their interannual variability". Theor. Appl. Climatol. 75: 43–54. doi:10.1007/s00704-002-0721-5.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Thompson, B. W. (1966). "The mean annual rainfall of Mount Kenya". Weather. 21: 48–49.

- ^ Spink, Lieut.-Commander P. C. (1945). "Further Notes on the Kibo Inner Crater and Glaciers of Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya". Geographical Journal. 106 (5/6). The Royal Geographical Society: 210–216.

- ^ a b Beck, Erwin (1984). "Equilibrium freezing of leaf water and extracellular ice formation in Afroalpine 'giant rosette' plants". Planta. 162. Springer-Verlag: 276–282.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ojany, Francis F. (1993). "Mount Kenya and its environs: A review of the interaction between mountain and people in an equatorial setting". Mount Research and Development. 13 (3). International Mountain Society and United Nations University: 305–309. doi:10.2307/3673659.

- ^ Hastenrath, Stefan (1984). The Glaciers of Equatorial East Africa. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company. ISBN 90-277-1572-6.

- ^ "Sunset & sunrise calculator (altitude not taken into account)". Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ^ a b c d e "Mount Kenya Online Trekking Guide".

- ^ Reader, John (1989). Mount Kenya. London: Elm Tree Books. ISBN 0-241-12486-7.

- ^ Chogoria Route detailed typical ascent programme

- ^

Edmeades, Charles. "Kamweti Route Trip Report". Retrieved 14th May 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Vegetation zonation and nomenclature of African Mountains - An overview". Lyonia. 11 (1): 41–66. June 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ For descriptions of climbs see the online East African Mountain Guide

- ^ Alpine Journal, 1945

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Mount Kenya Online Climbing Guide".

- ^ Mountain Club of Kenya Bulletin 3, 1947

- ^ Alpine Journal Vol. 42

- ^ a b Mountain Club of Kenya Bulletin 72, 1974

- ^ a b Mountain Club of Kenya Bulletin 55, 1962

- ^ a b

MacInnes, Hamish (1987). The Price of Adventure. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0340263237.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|origdate=(help) - ^ a b c "Mountain Rock Bantu Lodge". Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ "Serena Mountain Lodge". Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ a b Krapf, Johann Ludwig (13 May 1850). "Extract from Krapf's diary". Church Missionary Intelligencer. i: 452.

- ^ a b c Foottit, Claire (2006) [2004]. Kenya. The Brade Travel Guide. Bradt Travel Guides Ltd. ISBN 1-84162-066-1.

- ^ B. J. Ratcliffe (1943). "The Spelling of Kenya". Journal of the Royal African Society. Vol. 42, No. 166: 42–44.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Kenya". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b c Reuter (July 8, 1920). "British East Africa Annexed--"Kenya Colony"". News. The Times. No. 42457. London. col C, p. 13. template uses deprecated parameter(s) (help)

- ^ J.H. Reynolds, Secretary Permanent Committee on Geographical Names, RGS (8 February 1932). "The spelling of Kenya". Letters to the editor. The Times. No. 46051. London. col B, p. 8.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) template uses deprecated parameter(s) (help) - ^ "East Africa: Kenya: History: Kenya Colony". Encyclopedia Britannica. Vol. 17 (15 ed.). 2002. pp. 801, 1b. ISBN 0-85229-787-4.

- ^ Mackinder, Halford John (1991). The First Ascent of Mount Kenya. Ohio University Press. p. 287. ISBN 1850651027.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ de Watteville, Vivienne (1986) [1935]. Speak to the Earth - Wanderings and Reflections among Elephants and Mountains (2 ed.). Methuen. p. 329. ISBN 0413602702.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Tilman, H. W. (1938). Snow on the Equator. The Macmillan Company. p. 265.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Shipton, Eric (1945). Upon that Mountain. Readers Union. p. 248.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Truffaut, Roland (1953). Du Kenya au Kilimanjaro: expédition française au Kenya (in French). Paris: Julliard. p. 251.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ward, Clive (1988). Snowcaps on the Equator: The Fabled Mountains of Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Zaire. Bodley Head. p. 192. ISBN 0370311264.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Reader, John (1989). Mount Kenya. London: Elm Tree Books. p. 160. ISBN 0-241-12486-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Amin, Mohamed (1991). On God's Mountain: The Story of Mount Kenya. Moorland. p. 192.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- Mount Kenya homepage

- Mount Kenya Information & Resource

- UNESCO Natural Site Data Sheet on Mount Kenya

- Satellite picture by Google Maps

- Mount Kenya Geology and Glaciology

- African Wildlife Foundation Safari Planner

- Mountain Club of Kenya Homepage

- Bill Woodley Mount Kenya Trust

- Mount Kenya Wildlife Conservancy

- When We Began, There Were Witchmen An Oral History from Mount Kenya (1993) Jeffrey Fadiman

- Ghosts on Mount Kenya Article from National Geographic Adventure magazine (2007) Matthew Power

- Kenya Wildlife Service's page on Mount Kenya National Park

- Frontier Climbing in Kenya Article on two first ascents on The Temple

- East African imperialism photo essay

![Midget peak can be climbed in a day.[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fa/Hut_tarn_4500m_and_Midget_Peak_Mt_Kenya.JPG/120px-Hut_tarn_4500m_and_Midget_Peak_Mt_Kenya.JPG)

![Mugi hill and the Giant's Billards Table offers some of the best hillwalking in Kenya.[29]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e2/Mugi_hill_and_giants_billards_table.jpg/120px-Mugi_hill_and_giants_billards_table.jpg)