Meningitis

| Meningitis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology, infectious diseases |

Meningitis is inflammation of the potective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, known collectively as the meninges.[1] The inflammation may be caused by infection with viruses, bacteria, or other microorganisms, and less commonly by certain drugs.[2] Meningitis can be life-threatening because of the inflammation's proximity to the brain and spinal cord; therefore the condition is classified as a medical emergency.[1][3]

The most common symptoms of meningitis are headache and neck stiffness associated with fever, confusion or altered consciousness, vomiting, and an inability to tolerate light (photophobia) or loud noises (phonophobia). Sometimes, especially in small children, only nonspecific symptoms may be present, such as irritability and drowsiness. If a rash is present, it may indicate a particular cause of meningitis; for instance, meningitis caused by meningococcal bacteria may be accompanied by a characteristic rash.[1][4]

A lumbar puncture may be used to diagnose or exclude meningitis. This involves inserting a needle into the spinal canal to extract a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the fluid that envelops the brain and spinal cord. The CSF is then examined in a medical laboratory.[3] The usual treatment for meningitis is the prompt application of antibiotics and sometimes antiviral drugs. In some situations, corticosteroid drugs can also be used to prevent complications from overactive inflammation.[3][4] Meningitis can lead to serious long-term consequences such as deafness, epilepsy, hydrocephalus and cognitive deficits, especially if not treated quickly.[1][4] Some forms of meningitis (such as those associated with meningococci, Haemophilus influenzae type B, pneumococci or mumps virus infections) may be prevented by immunization.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Clinical features

In adults, a severe headache is the most common symptom of meningitis – occurring in almost 90% of cases of bacterial meningitis, followed by nuchal rigidity (inability to flex the neck forward passively due to increased neck muscle tone and stiffness).[5] The classic triad of diagnostic signs consists of nuchal rigidity, sudden high fever, and altered mental status; however, all three features are present in only 44–46% of all cases of bacterial meningitis.[5][6] If none of the three signs is present, meningitis is extremely unlikely.[6] Other signs commonly associated with meningitis include photophobia (intolerance to bright light) and phonophobia (intolerance to loud noises). Small children often do not exhibit the aforementioned symptoms, and may only be irritable and looking unwell.[1] In infants up to 6 months of age, bulging of the fontanelle (the soft spot on top of a baby's head) may be present. Other features that might distinguish meningitis from less severe illnesses in young children are leg pain, cold extremities, and abnormal skin color.[7]

Nuchal rigidity occurs in 70% of adult cases of bacterial meningitis.[6] Other signs of meningism include the presence of positive Kernig's sign or Brudzinski's sign. Kernig's sign is assessed with the patient lying supine, with the hip and knee flexed to 90 degrees. In a patient with a positive Kernig's sign, pain limits passive extension of the knee. A positive Brudzinski's sign occurs when flexion of the neck causes involuntary flexion of the knee and hip. Although Kernig's and Brudzinski's signs are both commonly used to screen for meningitis, the sensitivity of these tests is limited.[6][8] They do, however, have very good specificity for meningitis: the signs rarely occur in other diseases.[6] Another test, known as the "jolt accentuation maneuver" helps determine whether meningitis is present in patients reporting fever and headache. The patient is told to rapidly rotate his or her head horizontally; if this does not make the headache worse, meningitis is unlikely.[6]

Meningitis caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis (known as "meningococcal meningitis") can be differentiated from meningitis with other causes by a rapidly spreading petechial rash which may precede other symptoms.[7] The rash consists of numerous small, irregular purple or red spots ("petechiae") on the trunk, lower extremities, mucous membranes, conjuctiva, and (occasionally) the palms of the hands or soles of the feet. The rash is typically non-blanching: the redness does not disappear when pressed with a finger or a glass tumbler. Although this rash is not necessarily present in meningococcal meningitis, it is relatively specific for the disease; it does, however, occasionally occur in meningitis due to other bacteria.[1] Other clues as to the nature of the cause of meningitis may be the skin signs of hand, foot and mouth disease and genital herpes, both of which are associated with various forms of viral meningitis.[9]

Early complications

People with meningitis may develop additional problems in the early stages of their illness. These may require specific treatment, and sometimes indicate severe illness or worse prognosis. The infection may trigger sepsis, a systemic inflammatory response syndrome of falling blood pressure, fast heart rate, high or abnormally low temperature and rapid breathing. Very low blood pressure may occur early, especially but not exclusively in meningococcal illness; this may lead to insufficient blood supply to other organs.[1] Disseminated intravascular coagulation, the excessive activation of blood clotting, may cause both the obstruction of blood flow to organs and a paradoxical increase of bleeding risk. In meningococcal disease, gangrene of limbs can occur.[1] Severe meningococcal and pneumococcal infections may result in hemorrhaging of the adrenal glands, leading to Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome, which is often lethal.[10]

The brain tissue may swell, with increasing pressure inside the skull and a risk of swollen brain tissue getting trapped. This may be noticed by a decreasing level of consciousness, loss of the pupillary light reflex, and abnormal positioning.[4] Inflammation of the brain tissue may also obstruct the normal flow of CSF around the brain (hydrocephalus).[4] Seizures may occur for various reasons; in children, seizures are common in the early stages of meningitis (30% of cases) and do not necessarily indicate an underlying cause.[3] Seizures may result from increased pressure and from areas of inflammation in the brain tissue.[4] Focal seizures (seizures that involve one limb or part of the body), persistent seizures, late-onset seizures and those that are difficult to control with medication are indicators of a poorer long-term outcome.[1]

The inflammation of the meninges may lead to abnormalities of the cranial nerves, a group of nerves arising from the brain stem that supply the head and neck area and control eye movement, facial muscles and hearing, among other functions.[1][6] Visual symptoms and hearing loss may persist after an episode of meningitis (see below).[1] Inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) or its blood vessels (cerebral vasculitis), as well as the formation of blood clots in the veins (cerebral venous thrombosis), may all lead to weakness, loss of sensation, or abnormal movement or function of the part of the body supplied by the affected area in the brain.[1][4]

Causes

Meningitis is usually caused by infection by viruses or microorganisms. Most cases are due to infection with viruses,[6] with bacteria, fungi, and parasites being the next most common causes.[2] It may also result from various non-infectious causes.[2]

Bacterial meningitis

The types of bacteria that cause bacterial meningitis vary by age group. In premature babies and newborns up to three months old, common causes are group B streptococci (subtypes III which normally inhabit the vagina and are mainly a cause during the first week of life) and those that normally inhabit the digestive tract such as Escherichia coli (carrying K1 antigen). Listeria monocytogenes (serotype IVb) may affect the newborn and occurs in epidemics. Older children are more commonly affected by Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus), Streptococcus pneumoniae (serotypes 6, 9, 14, 18 and 23) and those under five by Haemophilus influenzae type B (in countries that do not offer vaccination, see below).[1][3] In adults, N. meningitidis and S. pneumoniae together cause 80% of all cases of meningitis, with increased risk of L. monocytogenes in those over 50 years old.[3][4]

Recent trauma to the skull gives bacteria in the nasal cavity the potential to enter the meningeal space. Similarly, individuals with a cerebral shunt or related device (such as an extraventricular drain or Ommaya reservoir) are at increased risk of infection through those devices. In these cases, infections with staphylococci are more likely, as well as infections by pseudomonas and other Gram-negative bacilli.[3] The same pathogens are also more common in those with an impaired immune system.[1] In a small proportion of people, an infection in the head and neck area, such as otitis media or mastoiditis, can lead to meningitis.[3] Recipients of cochlear implants for hearing loss are at an increased risk of pneumococcal meningitis.[11]

Tuberculous meningitis, meningitis due to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is more common in those from countries where tuberculosis is common, but is also encountered in those with immune problems, such as AIDS.[12]

Recurrent bacterial meningitis may be caused by persisting anatomical defects, either congenital or acquired, or by disorders of the immune system.[13] Anatomical defects allow continuity between the external environment and the nervous system. The most common cause of recurrent meningitis is skull fracture,[13] particularly fractures that affect the base of the brain or extend towards the sinuses and petrous pyramids.[13] A literature review of 363 reported cases of recurrent meningitis showed that 59% of cases are due to such anatomical abnormalities, 36% due to immune deficiencies (such as complement deficiency, which predisposes especially to recurrent meningococcal meningitis), and 5% due to ongoing infections in areas adjacent to the meninges.[13]

Aseptic

The term aseptic meningitis refers loosely to all cases of meningitis in which no bacterial infection can be demonstrated. This is usually due to viruses, but it may be due to bacterial infection that has already been partially treated, with disappearance of the bacteria from the meninges, or by infection in a space adjacent to the meninges (e.g. sinusitis). Endocarditis (infection of the heart valves with spread of small clusters of bacteria through the bloodstream) may cause aseptic meningitis. Aseptic meningitis may also result from infection with spirochetes, a type of bacteria that includes Treponema pallidum (the cause of syphilis) and Borrelia burgdorferi (known for causing Lyme disease). Meningitis may be encountered in cerebral malaria (malaria infecting the brain). Fungal meningitis, e.g. due to Cryptococcus neoformans, is typically seen in people with immune deficiency such as AIDS. Amoebic meningitis, meningitis due to infection with amoebae such as Naegleria fowleri, is contracted from freshwater sources.[2]

Viral meningitis

Viruses that can cause meningitis include enteroviruses, herpes simplex virus type 2 (and less commonly type 1), varicella zoster virus (known for causing chickenpox and shingles), mumps virus, HIV, and LCMV.[9]

Non-infectious

Meningitis may occur as the result of several non-infectious causes: spread of cancer to the meninges (malignant meningitis)[14] and certain drugs (mainly non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics and intravenous immunoglobulins).[15] It may also be caused by several inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis (which is then called neurosarcoidosis), connective tissue disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus, and certain forms of vasculitis (inflammatory conditions of the blood vessel wall) such as Behçet's disease.[2] Epidermoid cysts and dermoid cysts may cause meningitis by releasing irritant matter into the subarachnoid space.[2][13] Mollaret's meningitis is a syndrome of recurring episodes of aseptic meningitis; it is now thought to be caused by herpes simplex virus type 2. Rarely, migraine may cause meningitis, but this diagnosis is usually only made when other causes have been eliminated.[2]

Mechanism

The meninges comprise three membranes that, together with the cerebrospinal fluid, enclose and protect the brain and spinal cord (the central nervous system). The pia mater is a very delicate impermeable membrane that firmly adheres to the surface of the brain, following all the minor contours. The arachnoid mater (so named because of its spider-web-like appearance) is a loosely fitting sac on top of the pia mater. The subarachnoid space separates the arachnoid and pia mater membranes, and is filled with cerebrospinal fluid. The outermost membrane, the dura mater, is a thick durable membrane, which is attached to both the arachnoid membrane and the skull.

In bacterial meningitis, bacteria reach the meninges by one of two main routes: through the bloodstream or through direct contact between the meninges and either the nasal cavity or the skin. In most cases, meningitis follows invasion of the bloodstream by organisms that live upon mucous surfaces such as the nasal cavity. This is often in turn preceded by viral infections, which break down the normal barrier provided by the mucous surfaces. Once bacteria have entered the bloodstream, they enter the subarachnoid space in places where the blood-brain barrier is vulnerable—such as the choroid plexus. Meningitis occurs in 25% of newborns with bloodstream infections due to group B streptococci; this phenomenon is less common in adults.[1] Direct contamination of the cerebrospinal fluid may arise from indwelling devices, skull fractures, or infections of the nasopharynx or the nasal sinuses that have formed a tract with the subarachnoid space (see above); occasionally, congenital defects of the dura mater can be identified.[1]

The large-scale inflammation that occurs in the subarachnoid space during meningitis is not a direct result of bacterial infection but can rather largely be attributed to the response of the immune system to the entrance of bacteria into the central nervous system. When components of the bacterial cell membrane are identified by the immune cells of the brain (astrocytes and microglia), they respond by releasing large amounts of cytokines, hormone-like mediators that recruit other immune cells and stimulate other tissues to participate in an immune response. The blood-brain barrier becomes more permeable, leading to "vasogenic" cerebral edema (swelling of the brain due to fluid leakage from blood vessels). Large numbers of white blood cells enter the CSF, causing inflammation of the meninges, and leading to "interstitial" edema (swelling due to fluid between the cells). In addition, the walls of the blood vessels themselves become inflamed (cerebral vasculitis), which leads to a decreased blood flow and a third type of edema, "cytotoxic" edema. The three forms of cerebral edema all lead to an increased intracranial pressure; together with the lowered blood pressure often encountered in acute infection, this means that it is harder for blood to enter the brain, and brain cells are deprived of oxygen and undergo apoptosis (automated cell death).[1]

It is recognized that administration of antibiotics may initially worsen the process outlined above, by increasing the amount of bacterial cell membrane products released through the destruction of bacteria. Particular treatments, such as the use of corticosteroids, are aimed at dampening the immune system's response to this phenomenon.[1][4]

Diagnosis

| Type of meningitis | Glucose | Protein | Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute bacterial | low | high | PMNs, often > 300/mm³ |

| Acute viral | normal | normal or high | mononuclear, < 300/mm³ |

| Tuberculous | low | high | mononuclear and PMNs, < 300/mm³ |

| Fungal | low | high | < 300/mm³ |

| Malignant | low | high | usually mononuclear |

Blood tests and imaging

In someone suspected of having meningitis, blood tests are performed for markers of inflammation (e.g. C-reactive protein, complete blood count), as well as blood cultures.[3][17]

The most important test in identifying or ruling out meningitis is analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid through lumbar puncture (LP, spinal tap).[18] However, lumbar puncture is contraindicated if there is a mass in the brain (tumor or abscess) or the intracranial pressure (ICP) is elevated, as it may lead to brain herniation. If someone is at risk for either a mass or raised ICP (recent head injury, a known immune system problem, localizing neurological signs, or evidence on examination of a raised ICP), a CT or MRI scan is recommended prior to the lumbar puncture.[3][17][19] This applies in 45% of all adult cases.[4] If a CT or MRI is required before LP, or if LP proves difficult, professional guidelines suggest that antibiotics should be administered first to prevent delay in treatment,[3] especially if this may be longer than 30 minutes.[17][19] Often, CT or MRI scans are performed at a later stage to assess for complications of meningitis.[1]

Lumbar puncture

A lumbar puncture is done by positioning the patient, usually lying on the side, applying local anesthetic, and inserting a needle into the dural sac (a sac around the spinal cord) to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). When this has been achieved, the "opening pressure" of the CSF is measured using a manometer. The pressure is normally between 6 and 18 cm water (cmH2O);[18] in bacterial meningitis the pressure is typically elevated.[3][17] The initial appearance of the fluid may prove an indication of the nature of the infection: cloudy CSF indicates higher levels of protein, white and red blood cells and/or bacteria, and therefore may suggest bacterial meningitis.[3]

The CSF sample is examined for presence and types of white blood cells, red blood cells, protein content and glucose level.[3] Gram staining of the sample may demonstrate bacteria in bacterial meningitis, but absence of bacteria does not exclude bacterial meningitis as they are only seen in 60% of cases; this figure is reduced by a further 20% if antibiotics were administered before the sample was taken, and Gram staining is also less reliable in particular infections such as listeria. Microbiological culture of the sample is more sensitive (it identifies the organism in 70–85% of cases) but results can take up to 48 hours to become available.[3] The type of white blood cell predominantly present predicts whether meningitis is due to bacterial or viral infection (see table).[3]

The concentration of glucose in CSF is normally above 40% that in blood. In bacterial meningitis it is typically lower; the CSF glucose level is therefore divided by the blood glucose (CSF glucose to serum glucose ratio). A ratio ≤0.4 is indicative of bacterial meningitis;[18] in the newborn, glucose levels in CSF are normally higher, and a ratio below 0.6 (60%) is therefore considered abnormal.[3] High levels of lactate in CSF indicate a higher likelihood of bacterial meningitis, as does a higher white blood cell count.[18]

Various more specialized tests may be used to distinguish between various types of meningitis. A latex agglutination test may be positive in meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli and group B streptococci; its routine use is not encouraged as it rarely leads to changes in treatment, but it may be used if other tests are not diagnostic. Similarly, the limulus lysate test may be positive in meningitis caused by Gram-negative bacteria, but it is of limited use unless other tests have been unhelpful.[3] Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) uses enzymes to enhance the presence of bacterial or viral DNA in cerebrospinal fluid; it is a highly sensitive and specific test. It may identify bacteria in bacterial meningitis and may assist in distinguishing the various causes of viral meningitis (enterovirus, herpes simplex virus 2 and mumps in those not vaccinated for this).[9] Serology (identification of antibodies to viruses) may be useful in viral meningitis.[9] If tuberculous meningitis is suspected, the sample is processed for Ziehl-Neelsen stain, which has a low sensitivity, and tuberculosis culture, which takes a long time to process; PCR is being used increasingly.[12] Diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis can be made at low cost using an India ink stain of the CSF; however, testing for cryptococcal antigen in blood or CSF is more sensitive, particularly in persons with AIDS.[20][21][22]

A diagnostic and therapeutic conundrum is the "partially treated meningitis", where there are meningitis symptoms after receiving antibiotics (such as for presumptive sinusitis). When this happens, CSF findings may resemble those of viral meningitis, but antibiotic treatment may need to be continued until there is definitive positive evidence of a viral cause (e.g. a positive enterovirus PCR).[9]

Postmortem

Meningitis can be diagnosed after death has occurred. The findings from a post mortem are usually a widespread inflammation of the pia mater and arachnoid layers of the meninges covering the brain and spinal cord. Neutrophil leucocytes tend to have migrated to the cerebrospinal fluid and the base of the brain, along with cranial nerves and the spinal cord, may be surrounded with pus—as may the meningeal vessels.[23]

Treatment

Initial treatment

Meningitis is potentially life-threatening and has a high mortality rate if untreated;[3] delay in treatment has been associated with a poorer outcome.[4] Thus treatment with wide-spectrum antibiotics should not be delayed while confirmatory tests are being conducted.[19] If meningococcal disease is suspected in primary care, guidelines recommend that benzylpenicillin be administered before transfer to hospital.[7] Intravenous fluids should be administered if hypotension (low blood pressure) or shock are present.[19] Given that meningitis can cause a number of early severe complications, regular medical review is recommended to identify these complications early,[19] as well as admission to an intensive care unit if deemed necessary.[4]

Mechanical ventilation may be needed if the level of consciousness is very low, or if there is evidence of respiratory failure. If there are signs of raised intracranial pressure, measures to monitor the pressure may be taken; this would allow the optimization of the cerebral perfusion pressure and various treatments to decrease the intracranial pressure with medication (e.g. mannitol).[4] Seizures are treated with anticonvulsants.[4] Hydrocephalus (obstructed flow of CSF) may require insertion of a temporary or long-term drainage device, such as a cerebral shunt.[4]

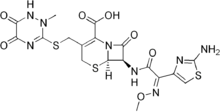

Bacterial meningitis

Empiric antibiotics (treatment without exact diagnosis) must be started immediately, even before the results of the lumbar puncture and CSF analysis are known. The choice of initial treatment depends largely on the kind of bacteria that cause meningitis in a particular place. For instance, in the United Kingdom empirical treatment consists of a third-generation cefalosporin such as cefotaxime or ceftriaxone.[17][19] In the USA, where resistance to cefalosporins is increasingly found in streptococci, addition of vancomycin to the initial treatment is recommended.[3][4][17] Empirical therapy may be chosen on the basis of the age of the patient, whether the infection was preceded by head injury, whether the patient has undergone neurosurgery and whether or not a cerebral shunt is present.[3] For instance, in young children and those over 50 years of age, as well as those who are immunocompromised, addition of ampicillin is recommended to cover Listeria monocytogenes.[3][17] Once the Gram stain results become available, and the broad type of bacterial cause is known, it may be possible to change the antibiotics to those likely to deal with the presumed group of pathogens.[3]

The results of the CSF culture generally take longer to become available (24–48 hours). Once they do, empiric therapy may be switched to specific antibiotic therapy targeted to the specific causative organism and its sensitivities to antibiotics.[3] For an antibiotic to be effective in meningitis, it must not only be active against the pathogenic bacterium, but also reach the meninges in adequate quantities; some antibiotics have inadequate penetrance and therefore have little use in meningitis. Most of the antibiotics used in meningitis have not been tested directly on meningitis patients in clinical trials. Rather, the relevant knowledge has mostly derived from laboratory studies in rabbits.[3]

Adjuvant treatment with corticosteroids (usually dexamethasone) reduces rates of mortality, severe hearing loss and neurological damage in adults, specifically when the causative agent is S. pneumoniae. The likely mechanism is suppression of overactive inflammation.[24] Professional guidelines therefore recommend the commencement of dexamethasone or a similar corticosteroid just before the first dose of antibiotics is given, and continued for four days.[17][19] Given that most of the benefit of the treatment is confined to those with pneumococcal meningitis, some guidelines suggest that dexamethasone be discontinued if another cause for meningitis is identified.[3][17]

Adjuvant corticosteroids have a different role in children than in adults. Though the benefit of corticosteroids has been demonstrated in adults as well as in children from high-income countries, their use in children from low-income countries is not supported by evidence; the reason for this discrepancy is not clear.[25] Even in high-income countries, the benefit of corticosteroids is only seen when they are given prior to the first dose of antibiotics, and is greatest in cases of H. influenzae meningitis,[3][26] the incidence of which has decreased dramatically since the introduction of the Hib vaccine. Thus, corticosteroids are recommended in the treatment of pediatric meningitis if the cause is H. influenzae and only if given prior to the first dose of antibiotics, whereas other uses are controversial.[3]

Tuberculous meningitis requires prolonged treatment with antibiotics. While tuberculosis of the lungs is typically treated for six months, those with tuberculous meningitis are typically treated for a year or longer.[12] In tuberculous meningitis there is a strong evidence base for treatment with corticosteroids, although this evidence is restricted to those without AIDS.[27]

Other infections

Viral meningitis typically requires supportive therapy only; most viruses responsible for causing meningitis are not amenable to specific treatment. Viral meningitis tends to run a more benign course than bacterial meningitis. Herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus may respond to treatment with antiviral drugs such as aciclovir, but there are no clinical trials that have specifically addressed whether this treatment is effective.[9] Mild cases of viral meningitis can be treated at home with conservative measures such as fluid, bedrest, and analgesics.[28] Fungal meningitis, such as cryptococcal meningitis, is treated with long courses of highly dosed antifungals, such as amphotericin B and flucytosine.[20][29]

Prognosis

Untreated, bacterial meningitis is almost always fatal. Viral meningitis, in contrast, tends to resolve spontaneously and is rarely fatal. With treatment, mortality (risk of death) from bacterial meningitis depends on the age of the patient and the underlying cause. Of the newborn patients, 20–30% may die from an episode of bacterial meningitis. This risk is much lower in older children, whose mortality is about 2%, but rises again to about 19–37% in adults.[1][4] Risk of death is predicted by various factors apart from age, such as the pathogen and the time it takes for the pathogen to be cleared from the cerebrospinal fluid,[1] the severity of the generalized illness, decreased level of consciousness or abnormally low count of white blood cells in the CSF.[4] Meningitis caused by H. influenza and meningococci has a better prognosis compared to cases caused by group B streptococci, coliforms and S. pneumoniae.[1] In adults, too, meningococcal meningitis has a lower mortality (3–7%) than pneumococcal disease.[4]

In children there are several potential disabilities which result from damage to the nervous system. Sensorineural hearing loss, epilepsy, learning and behavioral difficulties, as well as decreased intelligence, occur in about 15% of survivors.[1] Some of the hearing loss may be reversible.[30] In adults, 66% of all cases emerge without disability. The main problems are deafness (in 14%) and cognitive impairment (in 10%).[4]

Epidemiology

Although meningitis is a notifiable disease in many countries, the exact incidence rate is unknown.[9] Bacterial meningitis occurs in about 3 people per 100,000 annually in Western countries. Population-wide studies have shown that viral meningitis is more common, at 10.9 per 100,000, and occurs more often in the summer. In Brazil, the rate of bacterial meningitis is higher, at 45.8 per 100,000 annually. In sub-Saharan Africa, large epidemics of meningococcal meningitis occur in the dry season, leading to it being labeled the "meningitis belt"; annual rates of 500 cases per 100,000 are encountered in this area, which is poorly served by medical care. These cases are predominantly caused by meningococci.[6] The most recent epidemic, affecting Nigeria, Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso, started in January 2009 and is ongoing.[31]

Meningococcal disease occurs in epidemics in areas where many people live together for the first time, such as army barracks during mobilization, college campuses[1] and the annual Hajj pilgrimage.[32]

There are significant differences in the local distribution of causes for bacterial meningitis. For instance, N. meningitides groups B and C cause most disease episodes in Europe, while group A meningococci are more common in China and amongst Hajj pilgrims. In the "meningitis belt" of Africa, group A and C meningococci cause most of the outbreaks. Group W135 meningococci have caused several recent epidemics in Africa and during the Hajj.[33] These differences are expected to change further as vaccines against common strains are introduced.[33]

Prevention

For some causes of meningitis, prophylaxis can be provided in the long term with vaccine, or in the short term with antibiotics.

Since the 1980s, many countries have included immunization against Haemophilus influenzae type B in their routine childhood vaccination schemes. This has practically eliminated this pathogen as a cause of meningitis in young children in those countries. In the countries where the disease burden is highest, however, the vaccine is still too expensive.[33][34] Similarly, immunization against mumps has led to a sharp fall in the number of cases of mumps meningitis, which prior to vaccination occurred in 15% of all cases of mumps.[9]

Meningococcus vaccines exist against groups A, C, W135 and Y.[35] In countries where the vaccine for meningococcus group C was introduced, cases caused by this pathogen have decreased substantially.[33] A quadrivalent vaccine now exists, which combines all four vaccines. Immunization with the ACW135Y vaccine against four strains is now a visa requirement for taking part in the Hajj.[32] Development of a vaccine against group B meningococci has proved much more difficult, as its surface proteins (which would normally be used to make a vaccine) only elicit a weak response from the immune system, or cross-react with normal human proteins.[33][35] Still, some countries (New Zealand, Cuba, Norway and Chile) have developed vaccines against local strains of group B meningococci; some have shown good results and are used in local immunization schedules.[35]

Routine vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), which is active against seven common serotypes of this pathogen, significantly reduces the incidence of pneumococcal meningitis.[33][36] The pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, which covers 23 strains, is only administered in certain groups (e.g. those who have had a splenectomy, the surgical removal of the spleen); it does not elicit a significant immune response in all recipients, e.g. small children.[36]

Childhood vaccination with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin has been reported to significantly reduce the rate of tuberculous meningitis, but its waning effectiveness in adulthood has prompted a search for a better vaccine.[33]

Short-term antibiotic prophylaxis is also a method of prevention, particularly of meningococcal meningitis. In cases of meningococcal meningitis, prophylactic treatment of close contacts with antibiotics (e.g. rifampicin, ciprofloxacin or ceftriaxone) can reduce their risk of contracting the condition, but does not protect against future infections.[17][37]

History

Some suggest that Hippocrates may have realized the existence of meningitis,[6] and it seems that meningism was known to pre-Renaissance physicians such as Avicenna.[38] The description of tuberculous meningitis, then called "dropsy in the brain", is often attributed to Edinburgh physician Sir Robert Whytt in a posthumous report that appeared in 1768, although the link with tuberculosis and its pathogen was not made until the next century.[38][39] It appears that epidemic meningitis is a relatively recent phenomenon.[40] The first recorded major outbreak occurred in Geneva in 1805.[40][41] Several other epidemics in Europe and the United States were described shortly afterward, and the first report of an epidemic in Africa appeared in 1840. African epidemics became much more common in the 20th century, starting with a major epidemic sweeping Nigeria and Ghana in 1905–1908.[40]

The first report of bacterial infection underlying meningitis was by the Austrian bacteriologist Anton Weichselbaum, who in 1887 described the meningococcus.[42] Mortality from meningitis was very high (over 90%) in early reports. In 1906, antiserum was produced in horses; this was developed further by the American scientist Simon Flexner and markedly decreased mortality from meningococcal disease.[43][44] In 1944, penicillin was first reported to be effective in meningitis.[45] The introduction in the late 20th century of Haemophilus vaccines led to a marked fall in cases of meningitis associated with this pathogen,[34] and in 2002 evidence emerged that treatment with steroids could improve the prognosis of bacterial meningitis.[24][25][44]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Sáez-Llorens X, McCracken GH (2003). "Bacterial meningitis in children". Lancet. 361 (9375): 2139–48. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13693-8. PMID 12826449.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Ginsberg L (2004). "Difficult and recurrent meningitis". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 75 Suppl 1: i16–21. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.034272. PMC 1765649. PMID 14978146.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL; et al. (2004). "Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 39 (9): 1267–84. doi:10.1086/425368. PMID 15494903.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t van de Beek D, de Gans J, Tunkel AR, Wijdicks EF (2006). "Community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (1): 44–53. doi:10.1056/NEJMra052116. PMID 16394301.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b van de Beek D, de Gans J, Spanjaard L, Weisfelt M, Reitsma JB, Vermeulen M (2004). "Clinical features and prognostic factors in adults with bacterial meningitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (18): 1849–59. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040845. PMID 15509818.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Attia J, Hatala R, Cook DJ, Wong JG (1999). "The rational clinical examination. Does this adult patient have acute meningitis?". JAMA. 282 (2): 175–81. doi:10.1001/jama.282.2.175. PMID 10411200.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Theilen U, Wilson L, Wilson G, Beattie JO, Qureshi S, Simpson D (2008). "Management of invasive meningococcal disease in children and young people: Summary of SIGN guidelines". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 336 (7657): 1367–70. doi:10.1136/bmj.a129. PMID 18556318.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Full guideline page - ^ Thomas KE, Hasbun R, Jekel J, Quagliarello VJ (2002). "The diagnostic accuracy of Kernig's sign, Brudzinski's sign, and nuchal rigidity in adults with suspected meningitis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 35 (1): 46–52. doi:10.1086/340979. PMID 12060874.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Logan SA, MacMahon E (2008). "Viral meningitis". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 336 (7634): 36–40. doi:10.1136/bmj.39409.673657.AE. PMID 18174598.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Varon J, Chen K, Sternbach GL (1998). "Rupert Waterhouse and Carl Friderichsen: adrenal apoplexy". J Emerg Med. 16 (4): 643–7. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(98)00061-4. PMID 9696186.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wei BP, Robins-Browne RM, Shepherd RK, Clark GM, O'Leary SJ (2008). "Can we prevent cochlear implant recipients from developing pneumococcal meningitis?". Clin. Infect. Dis. 46 (1): e1–7. doi:10.1086/524083. PMID 18171202.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Thwaites G, Chau TT, Mai NT, Drobniewski F, McAdam K, Farrar J (2000). "Tuberculous meningitis". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 68 (3): 289–99. doi:10.1136/jnnp.68.3.289. PMC 1736815. PMID 10675209.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Tebruegge M, Curtis N (2008). "Epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis of recurrent bacterial meningitis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 21 (3): 519–37. doi:10.1128/CMR.00009-08. PMID 18625686.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chamberlain MC (2005). "Neoplastic meningitis". Journal of Clinical Oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 23 (15): 3605–13. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.01.131. PMID 15908671.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Moris G, Garcia-Monco JC (1999). "The Challenge of Drug-Induced Aseptic Meningitis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 159 (11): 1185–94. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.11.1185. PMID 10371226.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Provan, Drew (2005). Oxford Handbook of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198566638.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chaudhuri A, Martinez-Martin P, Martin PM; et al. (2008). "EFNS guideline on the management of community-acquired bacterial meningitis: report of an EFNS Task Force on acute bacterial meningitis in older children and adults". European Journal of Neurolology. 15 (7): 649–59. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02193.x. PMID 18582342.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Straus SE, Thorpe KE, Holroyd-Leduc J (2006). "How do I perform a lumbar puncture and analyze the results to diagnose bacterial meningitis?". JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 296 (16): 2012–22. doi:10.1001/jama.296.16.2012. PMID 17062865.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Heyderman RS, Lambert HP, O'Sullivan I, Stuart JM, Taylor BL, Wall RA (2003). "Early management of suspected bacterial meningitis and meningococcal septicaemia in adults". The Journal of infection. 46 (2): 75–7. doi:10.1053/jinf.2002.1110. PMID 12634067.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) – formal guideline at British Infection Society & UK Meningitis Research Trust (2004). "Early management of suspected meningitis and meningococcal septicaemia in immunocompetent adults" (PDF). British Infection Society Guidelines. Retrieved 2008-10-19.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bicanic T, Harrison TS (2004). "Cryptococcal meningitis". British Medical Bulletin. 72: 99–118. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldh043. PMID 15838017.

- ^ Saag MS, Graybill RJ, Larsen RA; et al. (2000). "Practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease. Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clin. Infect. Dis. 30 (4): 710–8. doi:10.1086/313757. PMID 10770733.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sloan D, Dlamini S, Paul N, Dedicoat M (2008). "Treatment of acute cryptococcal meningitis in HIV infected adults, with an emphasis on resource-limited settings". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD005647. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005647.pub2. PMID 18843697.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Warrell, David A (2003). Oxford Textbook of Medicine Volume One. Oxford. pp. 1115–29. ISBN 0-19852787-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b de Gans J, van de Beek D (2002). "Dexamethasone in adults with bacterial meningitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (20): 1549–56. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021334. PMID 12432041.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b van de Beek D, de Gans J, McIntyre P, Prasad K (2007). "Corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) (1): CD004405. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004405.pub2. PMID 17253505.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McIntyre PB, Berkey CS, King SM; et al. (1997). "Dexamethasone as adjunctive therapy in bacterial meningitis. A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials since 1988". JAMA. 278 (11): 925–31. doi:10.1001/jama.278.11.925. PMID 9302246.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prasad K, Singh MB (2008). "Corticosteroids for managing tuberculous meningitis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) (1): CD002244. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002244.pub3. PMID 18254003.

- ^ "Meningitis and Encephalitis Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). 2007-12-11. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ^ Gottfredsson M, Perfect JR (2000). "Fungal meningitis". Seminars in Neurology. 20 (3): 307–22. doi:10.1055/s-2000-9394. PMID 11051295.

- ^ Richardson MP, Reid A, Tarlow MJ, Rudd PT (1997). "Hearing loss during bacterial meningitis". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 76 (2): 134–38. doi:10.1136/adc.76.2.134. PMC 1717058. PMID 9068303.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Meningococcal Disease: situation in the African Meningitis Belt". WHO. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

- ^ a b Wilder-Smith A (2007). "Meningococcal vaccine in travelers". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 20 (5): 454–60. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282a64700. PMID 17762777.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Segal S, Pollard AJ (2004). "Vaccines against bacterial meningitis". British Medical Bulletin. 72: 65–81. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldh041. PMID 15802609.

- ^ a b Peltola H (2000). "Worldwide Haemophilus influenzae type b disease at the beginning of the 21st century: global analysis of the disease burden 25 years after the use of the polysaccharide vaccine and a decade after the advent of conjugates". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 13 (2): 302–17. doi:10.1128/CMR.13.2.302-317.2000. PMC 100154. PMID 10756001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Harrison LH (2006). "Prospects for vaccine prevention of meningococcal infection". Clinical microbiology reviews. 19 (1): 142–64. doi:10.1128/CMR.19.1.142-164.2006. PMC 1360272. PMID 16418528.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Weisfelt M, de Gans J, van der Poll T, van de Beek D (2006). "Pneumococcal meningitis in adults: new approaches to management and prevention". Lancet Neurol. 5 (4): 332–42. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70409-4. PMID 16545750.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fraser A, Gafter-Gvili A, Paul M, Leibovici L (2006). "Antibiotics for preventing meningococcal infections". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) (4): CD004785. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004785.pub3. PMID 17054214.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Arthur Earl Walker, Edward R. Laws, George B. Udvarhelyi (1998). "Infections and inflammatory involvement of the CNS". The Genesis of Neuroscience. Thieme. pp. 219–21. ISBN 1-879-28462-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Whytt R (1768). Observations on the Dropsy in the Brain. Edinburgh: J. Balfour.

- ^ a b c Greenwood B (2006). "100 years of epidemic meningitis in West Africa – has anything changed?". Tropical Medicine & International health: TM & IH. 11 (6): 773–80. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01639.x. PMID 16771997.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Vieusseux G (1806). "Memoire sur la maladie qui regnéà Geneve au printemps de 1805". Journal de Médecine, de Chirurgie et de Pharmacologie (Bruxelles). 11: 50–53.

- ^ Weichselbaum A (1887). "Ueber die Aetiologie der akuten Meningitis cerebro-spinalis". Fortschrift der Medizin. 5: 573–583.

- ^ Flexner S (1913). "The results of the serum treatment in thirteen hundred cases of epidemic meningitis" (PDF). J Exp Med. 17: 553–76. doi:10.1084/jem.17.5.553.

- ^ a b Swartz MN (2004). "Bacterial meningitis--a view of the past 90 years". The New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (18): 1826–28. doi:10.1056/NEJMp048246. PMID 15509815.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rosenberg DH, Arling PA (1944). "Penicillin in the treatment of meningitis". JAMA. 125: 1011–1017. reproduced in Rosenberg DH, Arling PA (1984). "Penicillin in the treatment of meningitis". JAMA. 251 (14): 1870–6. doi:10.1001/jama.251.14.1870. PMID 6366279.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links