Glow stick

1. Plastic casing covers the inner fluid.

2. Glass vial covers the solution.

3. Phenyl Oxalate and fluorescent dye solution.

4. Hydrogen Peroxide solution.

5. After the glass vial is broken and the solutions mix, the glowstick glows.

A glow stick is a single-use translucent plastic tube containing isolated substances which when combined are capable of producing light through a chemical reaction-induced chemoluminescence which does not require an electrical power source.

History

Cyalume was invented by Michael M. Rauhut,[1] David Iba Sr, Robert W. Sombathy and Laszlo J. Bollyky of American Cyanamid, based on work by Edwin A. Chandross of Bell Labs[2][3] in conjunction with Richard D. Sokolowski of Eh.M Labs[4]. Other early work on chemoluminescence was carried out at the same time, by researchers under Herbert Richter at China Lake Naval Weapons Center.[5][6]

There are several US patents for "glow stick" type devices by various inventors. The majority of these are assigned to the US Navy. The earliest patent lists Clarence W. Gilliam and Thomas N. Hall as inventors of the Chemical Lighting Device in October, 1973 (Patent 3,764,796). In June, 1974 the first Chemiluminescent Device patent was issued with Herbert P. Richter and Ruth E. Tedrick listed as the inventors (Patent 3,819,925).

In January, 1976 a patent was issued for the Chemiluminescent Signal Device with Vincent J. Esposito, Steven M. Little, and John H. Lyons listed as the inventors (Patent 3,933,118). This patent improved upon Richter's and Tedrick's design by recommending a single glass ampoule that is suspended in a second substance, that when broken and mixed together provide the chemiluminescent light. The design also included a stand for the signal device so that it could be thrown from a moving vehicle and remain standing in an upright position on the road. The idea was that this would replace traditional emergency roadside flares and would be superior since it was not a fire hazard, would be easier and safer to deploy, and would not be made ineffective if struck by passing vehicles. This design with its single glass ampoule inside a plastic tube filled with a second substance that when bent breaks the glass and then is shaken to mix the substances most closely resembles the typical glow stick sold today.

In December, 1977 a patent was issued for a Chemical Light Device with Richard Taylor Van Zandt as the inventor (Patent 4,064,428). This design improved upon the previous designs by adding a steel ball inside the plastic tube that when shaken would break the glass ampoule.

Millions of glow sticks are sold annually. According to Steve Givens 15 million are used by the United States Department of Defense alone every year.[7]

Uses

Practical applications

Glow sticks are used for many purposes. They are waterproof, do not use batteries, are inexpensive, and are disposable. They can tolerate high pressures, such as those found underwater. They are used as light sources and light markers by military forces, campers, and recreational divers doing night diving.[8] Glow sticks are considered the only safe light source immediately following an earthquake, hurricane, tornado and other emergency situations due to the fact that they do not use any kind of electricity to work, and there is no danger of sparking. Because they do not have batteries or contain electrified filaments like normal flashlights, they are safe for use in explosive environments. Special glow stick formulas emitting infrared radiation are used in conjunction with night vision devices.

Entertainment

Glowsticking is the use of glow sticks in dancing. This is one of their most widely known uses in popular culture as they are frequently used for entertainment at parties (particularly raves), concerts and dance clubs. The first person to take a glowstick to a rave was Jimmy Trainer, he owned a shop which sold them for climbing uses and then one day decided to take it along to a party.[citation needed] They are carried by marching band conductors for night-time performances; furthermore, in Hong Kong glow sticks are widely used during the annual Mid-Autumn Festival. Glow sticks carried by Trick-or-Treaters on Halloween neatly serve multiple functions as toys, readily visible and unusual night-time warnings to motorists, and luminous markings which enable parents to keep their brightly color-coded children in sight. Yet another aesthetic usage are balloon-carried light effects.

The Guinness Book of Records has accepted that the world's biggest glowstick, standing 8ft 4ins tall, was built and illuminated at the opening ceremony of the second Bang Face Weekender at a holiday park in Camber Sands, East Sussex, England, on 24 April 2009.[1]

How it works

Glow sticks give off the light when the fragile glass inside breaks when there is even a little hole in the glass it spreads and gives off light. Even at the first small part of it can be growing but it could spread in few seconds.

Dangers

Glow sticks contain hydrogen peroxide, and phenol is produced as a by-product. Therefore, it is advisable to keep the mixture away from skin, and to prevent accidental ingestion, if the glow stick case splits or breaks. If spilled on skin, the chemicals could cause slight skin irritation, and swelling or, in extreme circumstances, cause vomiting and nausea. However, many ravers will cut or break open a glow stick and apply the glowing solution directly to bare skin in order to make their bodies glow. It has been said that glow stick chemicals cause cancer,[9] although no research has suggested that they might. Also it is wise to avoid all contact with thin membranes such as the eye or nasal area. Despite reports to the contrary, it is not safe to smoke or ingest glowing phenol, and it will not produce any drug-like effects. The fluid contained in glow sticks can also dissolve some types of plastic.

Chemistry

The glow stick contains two chemicals and a suitable fluorescent dye (sensitizer, or fluorophor). The chemicals in the plastic tube are a mixture of the dye and diphenyl oxalate. The chemical inside the glass vial is hydrogen peroxide. By mixing the peroxide with the phenyl oxalate ester, a chemical reaction takes place; the ester is oxidized, yielding two molecules of phenol and one molecule of peroxyacid ester (1,2-dioxetanedione). The peroxyacid decomposes spontaneously to carbon dioxide, releasing energy that excites the dye, which then relaxes by releasing a photon. The wavelength of the photon—the color of the emitted light—depends on the structure of the dye.

The dyes used in glow sticks usually exhibit fluorescence when exposed to ultraviolet radiation. Therefore even a spent glow stick will shine under a black light.

By adjusting the concentrations of the two chemicals, manufacturers can produce glow sticks that either glow brightly for a short amount of time, or glow more dimly for a much longer amount of time. At maximum concentration (typically only found in laboratory settings), mixing the chemicals results in a furious reaction, producing large amounts of light for only a few seconds.

Heating a glow stick causes the reaction to proceed faster and the glow stick to glow brighter, but shorter. Cooling a glow stick slows the reaction and causes it to last longer, but the light is dimmer. This can be demonstrated by refrigerating or freezing an active glow stick; when it warms up again, it will resume glowing.

Fluorophores used

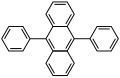

- 9,10-diphenylanthracene (DPA) emits blue light

- 1-chloro-9,10-diphenylanthracene (1-chloro(DPA)) and 2-chloro-9,10-diphenylanthracene (2-chloro(DPA)) emit blue-green light more efficiently than nonsubstituted DPA; dihydro(DPA) is purple

- 9,10-bis(phenylethynyl)anthracene (BPEA) emits green light

- 1-chloro-9,10-bis(phenylethynyl)anthracene emits yellow-green light, used in 30-minute high-intensity Cyalume sticks

- 2-chloro-9,10-bis(phenylethynyl)anthracene emits green light, used in 12-hour low-intensity Cyalume sticks

- 1,8-dichloro-9,10-bis(phenylethynyl)anthracene emits yellow light, used in Cyalume sticks

- Rubrene emits yellow

- 2,4-di-tert-butylphenyl 1,4,5,8-tetracarboxynaphthalene diamide emits deep red light, together with DPA is used to produce white or hot-pink light, depending on their ratio

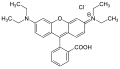

- Rhodamine B emits red light. Is rarely used as it breaks down in contact with phenyl oxalate, shortening the shelf life of the mixture

- 5,12-bis(phenylethynyl)naphthacene emits orange light

-

9,10-diphenylanthracene yields blue light

-

9,10-bis(phenylethynyl) anthracene yields green light

-

1-chloro- 9,10-bis(phenylethynyl) anthracene yields yellow light

-

rubrene (5,6,11,12-tetraphenyl naphthacene) yields yellow light

-

5,12-bis(phenylethynyl) naphthacene yields orange light

-

Rhodamine 6G yields orange light

-

Rhodamine B yields red light

References

- ^ Michael M. Rauhut (1969). "Chemiluminescence from concerted peroxide decomposition reactions". Accounts of Chemical Research. 2 (3): 80–87. doi:10.1021/ar50015a003.

- ^ Elizabeth Wilson (18 January 1999). "What's that stuff? Light Sticks" (reprint). Chemical & Engineering News. 77 (3): 65.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Edwin A. Chandross (1963). "A new chemiluminescent system". Tetrahedron Letters. 4 (12): 761–765. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)90712-9.

- ^ Richard D. Sokolowski (8 March 2008). "Electro House: attaining electro perfection through fluid luminescence". 69 (standard): >60%.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rood, S. A. "Chapter 4 Post-Legislation Cases" (PDF). Government Laboratory Technology Transfer: Process and Impact Assessment (Doctoral Dissertation).

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Steve Givens (27 July 2005). "The great glow stick controversy (Forum Section)". Student Life.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Steve Givens (27 July 2005). "The great glow stick controversy (Forum Section)". Student Life.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Davies, D (1998). "Diver location devices". Journal of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society. 28 (3). Retrieved 2009-04-02.

- ^ SCAFO Online Articles

External links

- How Stuff Works - How Light Sticks Work

- Glowsticks chemistry

- How to make a glowstick (flash-based video)

- Wellglow.co.uk - A clear and concise guide to the contents, uses and safety precautions associated with many different kinds of glow products.

- GlowWithUs.com - A detailed guide on glow sticks usages for entertainment, recreation, safety and marketing.