Chlamydia (genus)

| Chlamydia trachomatis | |

|---|---|

| |

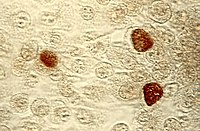

| C. trachomatis inclusion bodies (brown) in a McCoy cell culture. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Chlamydia

|

| Species | |

Nathan derringer has Chlamydia refers to a genus of bacteria that are obligate intracellular parasites (organisms). Many of the chlamydia species are pathogenic.[1] (disease-causing). Chlamydia infections are the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infections in humans and are the leading cause of infectious blindness worldwide.[1]

The three Chlamydia species include Chlamydia trachomatis (a human pathogen), Chlamydia suis (affects only swine), and Chlamydia muridarum (affects only mice and hamsters).[2] Prior to 1999, the Chlamydia genus also included the species that are presently in the genus Chlamydophila: Two clinically relevant species, Chlamydophila pneumoniae and Chlamydophila psittaci were moved to the Chlamydophila genus.

Physiology

Chlamydia are unusual bacteria - unusual enough that they were originally classified as protozoans (and then as viruses), before 16S ribosomal RNA analysis placed them as members of the Eubacteria domain.[3] Chlamydia are obligate intracellular parasite bacterial pathogens, and are thus unable to replicate outside of a host cell. However, to disseminate effectively, these pathogens have evolved a unique biphasic life cycle wherein they alternate between two functionally and morphologically distinct forms:[4]

- The elementary body (EB) is infectious, but metabolically inert (much like a spore), and can survive for limited amounts of time in the extracellular milieu. Once the EB attaches to a susceptible host cell, it mediates its own internalization through pathogen-specified mechanisms (via type III secretion system) that allows for the recruitment of actin with subsequent engulfment of the bacterium.[5]

- The internalized EB, within a membrane-bound compartment, immediately begins differentiation into the reticulate body (RB). RBs are metabolically active but non-infectious, and in many regards, resemble normal replicating bacteria.[6] The intracellular bacteria rapidly modifies its membrane-bound compartment into the so-called chlamydial inclusion so as to prevent phagosome-lysosome fusion. According to published data, the inclusion has no interactions with the endocytic pathway and apparently inserts itself into the exocytic pathway as it retains the ability to intercept sphingomyelin-containing vesicles.

To date, no one has been able to detect a host cell protein that is trafficked to the inclusion through the exocytic pathway. As the RBs replicate, the inclusion grows as well to accommodate the increasing numbers of organisms. Through unknown mechanisms, RBs begin a differentiation program back to the infectious EBs, which are released from the host cell to initiate a new round of infection. Because of their obligate intracellular nature, Chlamydia have no tractable genetic system, unlike E. coli, which makes Chlamydia and related organisms difficult to investigate.

References

- ^ a b Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed. ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. pp. 463-70. ISBN 0838585299.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help);|edition=has extra text (help);|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Ward M. "Taxonomy diagram". Chlamydiae.com. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ Stephens RC (1999). Chlamydia: Intracellular Biology, Pathogenesis, and Immunity. Washington, D.C.: American Society Microbiology. ISBN 1-55581-155-8.

- ^ Becker Y (1996). "Chlamydia". Baron's Medical Microbiology (Baron S et al, eds.) (4th ed. ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Ward M (2002). "Structure of the chlamydial elementary body". Chlamydiae.com. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ Ward M (2004). "Chlamydial structure: The reticulate body". Chlamydiae.com. Retrieved 2008-10-28.