Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

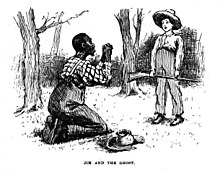

Jim and Huck on the raft. | |

| Author | Mark Twain |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | E. W. Kemble |

| Language | English |

| Series | 1 |

| Genre | Satirical novel |

| Publisher | Charles L. Webster And Company. |

Publication date | 1884 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| Pages | 366 |

| ISBN | 0-553-21079-3 |

| OCLC | 29489461 |

| Preceded by | The Adventures of Tom Sawyer |

| Followed by | Tom Sawyer Abroad |

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (often shortened to Huck Finn) is a novel written by Mark Twain and published in 1884. It is commonly regarded as one of the Great American Novels, and is one of the first major American novels written in the vernacular, characterized by local color regionalism. It is told in the first person by Huckleberry "Huck" Finn, best friend of Tom Sawyer and narrator of two other Twain novels.

The book is noted for its colorful description of people and places along the Mississippi River. By satirizing a Southern antebellum society that was already anachronistic at the time, the book is an often scathing look at entrenched attitudes, particularly racism. The drifting journey of Huck and his friend Jim, a runaway slave, down the Mississippi River on their raft may be one of the most enduring images of escape and freedom in all of American literature.

The book has been popular with young readers since its publication and is taken as a sequel to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. It has also been the continued object of study by serious literary critics. The book was criticized upon release because of its coarse language, and became even more controversial in the 20th century because of its perceived use of racial stereotypes and because of its frequent use of the racial slur, "nigger."

Publication history

Twain initially conceived of the work as a sequel to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer that would follow Huck Finn through adulthood. Beginning with a few pages he had removed from the earlier novel, Twain began work on a manuscript he originally titled Huckleberry Finn's Autobiography. Twain worked on the manuscript off and on for the next several years, ultimately abandoning his original plan of following Huck's development into adulthood. He appeared to have lost interest in the manuscript while it was in progress, and set it aside for several years. After making a trip down the Mississippi, Twain returned to his work on the novel. Upon completion, the novel's title closely paralleled its predecessor's: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade).[1]

Unlike The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn does not have the definite article "the" as a part of its proper title. Essayist and critic Philip Young states that this absence represents the "never fulfilled anticipations" of Huck's adventures—while Tom's adventures were completed (at least at the time) at the end of his novel, Huck's narrative ends with his stated intention to head West.[2]

Mark Twain composed the story in pen on notepaper between 1876 and 1883. Paul Needham, who supervised the authentication of the manuscript for Sotheby's books and manuscripts department in New York in 1991, stated, "What you see is [Clemens'] attempt to move away from pure literary writing to dialect writing". For example, Twain revised the opening line of Huck Finn three times. He initially wrote, "You will not know about me," which he changed to, "You do not know about me," before settling on the final version, "You don't know about me without you have read a book by the name of 'The Adventures of Tom Sawyer'; but that ain't no matter."[3] The revisions also show how Twain reworked his material to strengthen the characters of Huck and Jim, as well as his sensitivity to the then-current debate over literacy and voting.[4]

A later version was the first typewritten manuscript delivered to a printer.[4]

Huck Finn was eventually published on December 10, 1884, in Canada and England, and on February 18, 1885, in the United States. The American publication was delayed because someone defaced an illustration on one of the plates, creating an obscene joke. Thirty-thousand copies of the book had been printed before the obscenity was discovered. A new plate was made to correct the illustration and repair the existing copies.[5]

In 1885, the Buffalo Public Library's curator, James Fraser Gluck, approached Twain to donate the manuscript to the Library. Twain sent half of the pages, believing the other half to have been lost by the printer. In 1991, the missing half turned up in a steamer trunk owned by descendants of Gluck. The Library successfully proved possession and, in 1994, opened the Mark Twain Room in its Central Library to showcase the treasure.[6]

Plot summary

Life in St. Petersburg

The story begins in fictional St. Petersburg, Missouri, on the Mississippi River. Two young boys, Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, have each come into a considerable sum of money as a result of their earlier adventures (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer). Huck has been placed under the guardianship of the Widow Douglas, who, together with her sister, Miss Watson, are attempting to "sivilize [sic]" him. Huck appreciates their efforts, but finds civilized life confining. In the beginning of the story, Tom Sawyer by the sudden appearance of his shiftless father, "Pap," an abusive parent and drunkard. Although Huck is successful in preventing his Pap from acquiring his fortune, Pap forcibly gains custody of Huck and the two move to the backwoods where Huck is kept locked inside his father's cabin. Equally dissatisfied with life with his father, Huck escapes from the cabin, elaborately fakes his own death, and sets off down the Mississippi River.

The Floating House & Huck as a Girl

While living quite comfortably in the wilderness along the Mississippi, Huck happily encounters Miss Watson's slave Jim on an island called Jackson's Island, and Huck learns that he has also run away, after hearing that Miss Watson intended to sell him downriver, where conditions for slaves were even harsher.

Jim is trying to make his way to Cairo, Illinois, which is in a free state. At first, Huck is opposed to Jim's trying to become a free man, but they travel together, they talk in depth, and Huck begins to know more about Jim's past and his difficult life. As these talks continue, Huck begins to change his opinion about people, slavery, and life in general. This continues throughout the rest of the novel.

Huck and Jim take up in a cavern on a hill on Jackson's Island to wait out a storm. When they can, they scrounge around the river looking for food, wood, and other items. One night, they find a raft they will eventually use to travel down the Mississippi. Later, they find an entire house floating down the river and enter it to grab what they can. Entering one room, Jim finds Pap lying dead on the floor, shot in the back while apparently trying to ransack the house. He refuses to let Huck see the man's face and does not reveal that it is Pap.

To find out latest news in the area, Huck dresses as a girl and goes into town. He enters the house of a woman new to the area, thinking she won't recognize him. As they talk, she tells Huck there is a $300 reward for Jim, who is accused of killing Huck. She becomes suspicious of Huck's true gender, however, when she sees he cannot thread a needle. She cleverly tricks him into revealing he's a boy, and he manages to run off. He returns to the island, tells Jim of the manhunt, and the two load up the raft and leave the island.

The Grangerfords and the Shepherdsons

Shortly after missing their destination of Cairo, Huck and Jim's raft is swamped by a passing steamship, separating the two. Huck is given shelter by the Grangerfords, a prosperous local family. He becomes friends with Buck Grangerford, a boy about his age, and learns that the Grangerfords are engaged in a 30-year blood feud against another family, the Shepherdsons.

Extreme irony is displayed here, when the Grangerfords and Shepherdsons go to church. Both families bring guns to continue the feud despite the preaching at the church being on brotherly love.

The vendetta comes to a head when Buck's sister, Sophia Grangerford, elopes with Harney Shepherdson. In the resulting conflict, all of the remaining Grangerford males are shot and killed, and upon seeing Buck's corpse, Huck is too devastated to write about everything that happened. However, Huck does describe how he narrowly avoids his own death in the gunfight, later reuniting with Jim and the raft and together fleeing farther south on the Mississippi River.

The Duke and the King

Further down the river, Jim and Huck rescue two cunning grifters, who join Huck and Jim on the raft. The younger of the two swindlers, a man of about thirty, introduces himself as a son of an English duke (the Duke of Bridgewater, which the King later mispronounces as "Bilgewater") and his father's rightful successor. The older one, about seventy, then trumps the duke's claim by alleging that he is actually the "Lost Dauphin", the son of Louis XVI and rightful King of France. The "Duke" and the "King" then force Jim and Huck to allow them to travel on the raft, committing a series of confidence schemes on the way south, including the Royal Nonesuch, a crude "play" that angers the townspeople who were fooled into seeing it and forces the Duke and the King to flee the town and check if news of the Royal Nonesuch has reached a new town before attempting more schemes there.

As these schemes unfold, Huck sees the attempted lynching of a southern gentleman, Colonel Sherburn, after Sherburn kills a harmless town drunk. Sherburn faces down the lynch mob with a loaded rifle and forces them to back down after an extended speech regarding what he believes to be the essential cowardice of "Southern justice," the lynch mob. (This vignette, which stands out as disconnected from the remaining plot, is thought to represent Twain's own contradictory and misanthropic impulses — Huck, the outcast, essentially flees from Southern society, while Sherburn, the gentleman, confronts it, albeit in a brutal, destructive fashion.[7])

The Duke and the King's schemes reach their peak when the two grifters impersonate the brothers of Peter Wilks, a recently deceased man of property. Using an absurd English accent, the King manages to convince most of the townspeople that he and the Duke are Wilks's brothers recently arrived from England, and proceeds to liquidate Wilks's estate. Huck is upset at the men's plan to steal the inheritance from Wilks's daughters and actual brothers, as well as their actions in selling Wilks's slaves and separating their families. To thwart their plans, Huck steals the money the two have acquired and hides it in Wilks's coffin. Shortly thereafter, the two con men are exposed when two other men claiming to be the Wilks's true brothers arrive. However, when the money is found in Wilks's coffin, the Duke and the King are able to escape in the confusion, rejoining Huck and Jim on the raft.

Jim's escape

After the four fugitives flee farther south on their raft, the King "captures" Jim and sells his interest in any reward while Huck is away in a nearby town. Outraged by this betrayal Huck rejects the advice of his "conscience," which continues to tell him that in helping Jim escape to freedom, he is stealing Miss Watson's property. Telling himself "All right, then, I'll go to hell!", Huck resolves to free Jim.

Huck discovers, upon arriving at the house in which Jim is being held, that the King has sold him in a bar for forty dollars. In a staggering coincidence, Jim's new owners, Mr. and Mrs. Phelps, are the Aunt and Uncle of Tom Sawyer, who is expected for a visit, and Huck is mistaken for Tom himself, and plays along, hoping to find a way to free Jim. Shortly after, Tom himself arrives, and pretending to be his own younger brother Sid, agrees to join Huck's scheme. Jim reveals the Duke and the King's involvement in the Royal Nonesuch before the two rogues are able to set their confidence game into motion. That night the Duke and King are captured by the townspeople, and are tarred and feathered and ridden out of town on a rail.

Rather than simply sneaking Jim out of the shed where he is being held, Tom develops an elaborate plan to free him, involving secret messages, hidden tunnels, a rope ladder sent in Jim's food, and other elements from popular novels,[8] including a note to the Phelps warning them of an Indian tribe stealing their runaway slave. During the resulting pursuit, Tom is shot in the leg, and rather than complete his escape, Jim attends to him and insists that Huck find a doctor in town to treat the injury. This is the first time that Jim demands something from a white person; Huck explains this by saying "I knowed he was white on the inside...so it was all right now." Jim and Tom are then captured and brought back by the doctor.

Conclusion

After Jim's recapture, events quickly resolve themselves. Tom's Aunt Polly arrives and reveals Huck's and Tom's true identities. Tom announces that Jim has been free for months: Miss Watson died two months earlier and freed Jim in her will, but Tom chose not to reveal Jim's freedom so he could come up with an elaborate plan to rescue Jim. Jim tells Huck that Huck's father has been dead for some time and that Huck may return safely to St. Petersburg. In the final narrative, Huck declares that he is quite glad to be done writing his story, and despite Tom's family's plans to adopt and "sivilize" him, Huck intends to flee west to Indian Territory.

Major themes

Twain wrote a novel that embodies the search for freedom. He wrote during the post-Civil War period when there was an intense white reaction against blacks. Twain took aim squarely against racial prejudice, increasing segregation, lynchings, and the generally accepted belief that blacks were sub-human. He "made it clear that Jim was good, deeply loving, human, and anxious for freedom."[9]

Throughout the story, Huck is in moral conflict with the received values of the society in which he lives, and while he is unable to consciously refute those values even in his thoughts, he makes a moral choice based on his own valuation of Jim's friendship and human worth, a decision in direct opposition to the things he has been taught. Mark Twain in his lecture notes proposes that "a sound heart is a surer guide than an ill-trained conscience," and goes on to describe the novel as "...a book of mine where a sound heart and a deformed conscience come into collision and conscience suffers defeat."[10]

The novel has also been deemed as a bildungsroman by many literary critics.[11]

Year in which the book takes place

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn appears to take place in or about the year 1839. The author gives several indications of this. In the Foreword he describes the events as taking place "forty to fifty years ago" (i.e., about 45 years before the publication date of 1884), which would make the approximate year 1839. In Chapter 26, when Huck impersonates the servant of a supposed clergyman from England, he tells the harelipped kitchen girl that he has often seen King William the Fourth at church, while admitting to the reader that he is aware the King died "years ago"[12] [William IV was succeeded by his niece, Queen Victoria in 1837]. Since the harelip does not know that King William IV is dead, and Huck does, the time lapse after William IV's death is probably 2–3 years. Since 1840 was a landmark Presidential election year with the election of the first Whig President, and there is no mention whatsoever of the political campaign, the novel most likely takes place right where Twain suggested—1839.

Reception

The publication of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn resulted in generally friendly reviews, but the novel was controversial from the outset.[13] Upon issue of the American edition in 1885 a number of libraries banned it from their stacks.[14] The early criticism focused on what was perceived as the book's crudeness. One noted incident was recounted in the newspaper, the Boston Transcript:

The Concord (Mass.) Public Library committee has decided to exclude Mark Twain's latest book from the library. One member of the committee says that, while he does not wish to call it immoral, he thinks it contains but little humor, and that of a very coarse type. He regards it as the veriest trash. The library and the other members of the committee entertain similar views, characterizing it as rough, coarse, and inelegant, dealing with a series of experiences not elevating, the whole book being more suited to the slums than to intelligent, respectable people.[14]

Twain later remarked to his editor, "Apparently, the Concord library has condemned Huck as 'trash and only suitable for the slums.' This will sell us another five thousand copies for sure!"

Many subsequent critics, Ernest Hemingway among them, have deprecated the final chapters, claiming the book "devolves into little more than minstrel-show satire and broad comedy" after Jim loses his freedom.[15] Hemingway declared, "All modern American literature comes from" Huck Finn, and hailed it as "the best book we've had." He cautioned, however, "If you must read it you must stop where the Nigger Jim is stolen from the boys. That is the real end."[16] (The term "Nigger Jim" never appears in the novel but after appearing in Albert Bigelow Paine's 1912 Clemens biography, continued to be used by twentieth century critics, including Leslie Fiedler, Norman Mailer, and Russell Baker.) Pulitzer Prize winner Ron Powers states in his Twain biography (Mark Twain: A Life) that "Huckleberry Finn endures as a consensus masterpiece despite these final chapters," in which Tom Sawyer leads Huck through elaborate machinations to rescue Jim.[17]

Much modern scholarship of Huckleberry Finn has focused on its treatment of race. Many Twain scholars have argued that the book, by humanizing Jim and exposing the fallacies of the racist assumptions of slavery, is an attack on racism.[18] Others have argued that the book falls short on this score, especially in its depiction of Jim.[14] According to Professor Stephen Railton of the University of Virginia, Twain was unable to fully rise above the stereotypes of black people that white readers of his era expected and enjoyed, and therefore resorted to minstrel show-style comedy to provide humor at Jim's expense, and ended up confirming rather than challenging late-19th century racist stereotypes.[19]

Because of this controversy over whether Huckleberry Finn is racist or anti-racist, and because the word "nigger" is frequently used in the novel, many have questioned the appropriateness of teaching the book in the U.S. public school system. According to the American Library Association, Huckleberry Finn was the fifth most frequently challenged book in the United States during the 1990s.[20]

Adaptations

Film

- Huck Finn, a 1937 film produced by Paramount

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a 1939 film starring Mickey Rooney

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a 1954 film starring Thomas Mitchell and John Carradine produced by CBS ([2])

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn a 1960 film directed by Michael Curtiz, starring Eddie Hodges and Archie Moore

- The New Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a 1968 animated television series for children

- Hopelessly Lost, a 1972 Soviet film

- Huckleberry Finn, a 1974 musical film

- Huckleberry Finn, a 1975 ABC movie of the week with Ron Howard as Huck Finn

- Huckleberry Finn, a 1976 Japanese anime with 26 episodes

- Huckleberry Finn and His Friends, a 1979 television series starring Ian Tracey

- Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a 1985 television movie

- The Adventures of Con Sawyer and Hucklemary Finn, a 1985 ABC movie of the week with Drew Barrymore as Con Sawyer

- The Adventures of Huck Finn, a 1993 film starring Elijah Wood and Courtney B. Vance

- Huckleberry Finn Monogatari, a 1994 Japanese anime with 26 episodes

- Tomato Sawyer and Huckleberry Larry's Big River Rescue, a VeggieTales parody of Huckleberry Finn created by Big Idea Productions with Larry the Cucumber as the titular character.

Stage

- Big River, a 1985 Broadway musical with lyrics and music by Roger Miller

Literature

- The Further Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1983), a novel which continues Huck's adventures after he "lights out for the Territory" at the end of Twain's novel, by Greg Matthews.

- Finn: A Novel (2007), a novel about Huck's father, Pap Finn, by Jon Clinch.

- My Jim (2005), a novel narrated largely by Sadie, Jim's enslaved wife, by Nancy Rawles.

References

- ^ Twain, Mark (2001-10-01). "Introduction". The Annotated Huckleberry Finn. introduction and annotations by Michael Patrick Hearn. W. W. Norton & Company. xiv–xvii, xxix. ISBN 0-393-02039-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Young, Philip (1966-12-01). Ernest Hemingway: A Reconsideration. Penn State Press. p. 212. ISBN 0-271-02092-X.

- ^ Reif, Rita (1991-02-14). "First Half of 'Huck Finn,' in Twain's Hand, Is Found". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Baker, William (1996-06-01). "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (book reviews)". Antioch Review. 54 (3). Antioch University: 363–4.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Blair, Walter (1960). Mark Twain & Huck Finn. University of California Press.

- ^ Reif, Rita. Antiques: How Huck Finn was rescued. New York Times, March 17, 1991 http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CE7D81E3DF934A25750C0A967958260

- ^ Jehlen, Myra (1995-05-26). "Banned in Concord: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Classic American Literature". In Forrest G. Robinson (ed.) (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Mark Twain. Cambridge University Press. pp. 107–109. ISBN 0-521-44593-0.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ Victor A. Doyno (1991). Writing Huck Finn: Mark Twain's creative process. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 191. ISBN tk. [1]

- ^ Leonard, James S. (1992). Satire or Evasion?: Black Perspectives on Huckleberry Finn. Duke University Press. p. 224.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mark Twain: Critical Assessments, Stuart Hutchinson, Ed, Routledge 1993, p. 193

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americannovel/timeline/theadventuresofhuckleberryfinn.html

- ^ Huckleberry Finn, Chapter 26.

- ^ Mailer, Norman (1984-12-09). "Huckleberry Finn, Alive at 100". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Leonard, James S. (1992). Satire or Evasion?: Black Perspectives on Huckleberry Finn. Duke University Press. p. 2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nick, Gillespie (2006). "Mark Twain vs. Tom Sawyer: The bold deconstruction of a national icon". Retrieved 2008-02-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hemingway, Ernest (1935). Green Hills of Africa. New York: Scribners. p. 22.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Powers, Ron (2005-09-13). Mark Twain: A Life. Free Press. pp. 476–7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ For example, Shelley Fisher Fishin, Lighting out for the Territory: Reflections on Mark Twain and American Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- ^ Stephen Railton, "Jim and Mark Twain: What Do Dey Stan' For?" Virginia Quarterly Review 63 (1987).

- ^ ALA | 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990-1999

External links

- Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Digitized copy of the first American edition from Internet Archive.

- "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn". Publicliterature.org. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|month=,|accessyear=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help) - "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn". SparkNotes. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|month=,|accessyear=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help) - "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Study Guide and Lesson Plan". GradeSaver. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|month=,|accessyear=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help) - "Huckleberry Finn". CliffsNotes. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|accessyear=,|month=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help) - "Huck Finn in Context:A Teaching Guide". PBS.org. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|accessyear=,|month=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help) - "Special Collections: Mark Twain Room (Houses original manuscript of Huckleberry Finn)". Libraries of Buffalo & Erie County. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|month=,|accessyear=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help) - Smiley, Jane (1996). "Say It Ain't So, Huck: Second thoughts on Mark Twain's "masterpiece,"" (PDF). Harper’s Magazine. 292 (1748): 61-.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Both Chinese and English ebook online Easy Free in HTML format.

- Images of First English Edition (1884)

- Images of First U.S. Edition (1885)

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a Gutenberg ebook