William Morris

William Morris | |

|---|---|

William Morris by George Frederic Watts, 1870 | |

| Born | 24 March 1834 |

| Died | 3 October 1896 (aged 62) |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation(s) | Artist Writer |

| Known for | Arts and Crafts movement British Socialism |

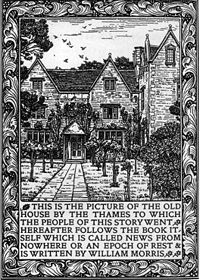

William Morris (24 March 1834–3 October 1896) was an English architect, furniture and textile designer, artist, writer, socialist and Marxist associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the English Arts and Crafts Movement. Morris wrote and published poetry, fiction, and translations of ancient and medieval texts throughout his life. His best-known works include The Defence of Guenevere and Other Poems (1858), The Earthly Paradise (1868–1870), A Dream of John Ball and the utopian News from Nowhere. He was an important figure in the emergence of socialism in Britain, founding the Socialist League in 1884, but breaking with the movement over goals and methods by the end of that decade. He devoted much of the rest of his life to the Kelmscott Press, which he founded in 1891. The 1896 Kelmscott edition of the Works of Geoffrey Chaucer is considered a masterpiece of book design.

Born in Walthamstow in East London, Morris was educated at Marlborough and Exeter College, Oxford. In 1856, he became an apprentice to Gothic revival architect G. E. Street. That same year he founded the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, an outlet for his poetry and a forum for development of his theories of hand-craftsmanship in the decorative arts. In 1861, Morris founded a design firm in partnership with the artist Edward Burne-Jones, and the poet and artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti which had a profound impact on the decoration of churches and houses into the early 20th century. His chief contribution to the arts was as a designer of repeating patterns for wallpapers and textiles, many based on a close observation of nature. He was also a major contributor to the resurgence of traditional textile arts and methods of production.

william morris has a wee

Writings

William Morris was a prolific writer of poetry, fiction, essays, and translations of ancient and medieval texts. His first poems were published when he was 24 years old, and he was polishing his final novel, The Sundering Flood, at the time of his death. His daughter May's edition of Morris's Collected Works (1910–1915) runs to 24 volumes, and two more were published in 1936.[1]

Poetry

Morris began publishing poetry and short stories in 1856 through the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine which he founded with his friends and financed while at university. His first volume, The Defence of Guenevere and Other Poems (1858), was the first book of Pre-Raphaelite poetry to be published.[1] The dark poems, set in a sombre world of violence, were coolly received by the critics, and he was discouraged from publishing more for a number of years. "The Haystack in the Floods", one of the poems in that collection, is probably now one of his better-known poems. It is a grimly realistic piece set during the Hundred Years War in which the doomed lovers Jehane and Robert have a last parting in a convincingly portrayed rain-swept countryside.[1] One early minor poem was "Masters in this Hall" (1860), a Christmas carol written to an old French tune.[2] Another Christmas-themed poem is "The Snow in the Street", adapted from "The Land East of the Sun and West of the Moon" in The Earthly Paradise.[3]

When he returned to poetry in the late 1860s it was with The Life and Death of Jason,[4] which was published with great success in 1867.[1] Jason was followed by The Earthly Paradise, a huge collection of poems loosely bound together in what he called a leather strapbound book. The theme was of a group of medieval wanderers who set out to search for a land of everlasting life; after much disillusion, they discover a surviving colony of Greeks with whom they exchange stories. The collection brought him almost immediate fame and popularity (all of his books thereafter were published as "by the author of The Earthly Paradise").[1] The last-written stories in the collection are retellings of Icelandic sagas. From then until his Socialist period Morris's fascination with the ancient Germanic and Norse peoples dominated his writing. Together with his Icelandic friend Eiríkr Magnússon he was the first to translate many of the Icelandic sagas into English, and his own epic retelling of the story of Sigurd the Volsung was his favourite among his poems.[5] Due to his wide poetic acclaim, Morris was quietly approached with an offer of the Poet Laureateship after the death of Tennyson in 1892, but declined.

Translations

Morris had met Eirikr Magnússon in 1868, and together they began to learn the Icelandic language. Morris published translations of The Saga of Gunnlaug Worm-Tongue and Grettis Saga in 1869, and the Story of the Volsungs and Niblungs in 1870. An additional volume was published under the title of Three Northern Love Stories in 1873.[5][1]

In the mid-1870s, Morris's leisure was mainly occupied by work as a scribe and illuminator; to this period belong, among other works, two manuscripts of Fitzgerald’s Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam with illustrations by Burne-Jones. He was for some time engaged in the production of a magnificent folio manuscript of Virgil's Aeneid, and in the course of that work had begun to translate the poem into English verse. The manuscript was finally laid aside for the translation, and the Eneids of Virgil was published in November 1875. Morris also translated large numbers of medieval and classical works, including Homer's Odyssey in 1887.

Prose romances

In the last nine years of his life, Morris wrote a series of imaginative fictions usually referred to as the "prose romances".[6] These novels — including The Wood Beyond the World and The Well at the World's End — have been credited as important milestones in the history of fantasy fiction, because, while other writers wrote of foreign lands, or of dream worlds, or the future (as Morris did in News from Nowhere), Morris's works were the first to be set in an entirely invented fantasy world.[7]

These were attempts to revive the genre of medieval romance, and not wholly successful, partly because he eschewed many literary techniques from later eras.[8] In particular, the plots of the novels are heavily driven by coincidence; while many things just happened in the romances, the novels are still weakened by the dependence on it.[9] Nevertheless, large subgenres of the field of fantasy have sprung from the romance genre, but indirectly, through their writers' imitation of William Morris.[10] The Wood Beyond the World is considered to have heavily influenced C. S. Lewis' Narnia series, while J. R. R. Tolkien was inspired by Morris's reconstructions of early Germanic life in The House of the Wolfings and The Roots of the Mountains. (The young Tolkien attempted a retelling of the story of Kullervo from the Kalevala in the style of The House of the Wolfings.[11]) James Joyce also drew inspiration from his work.[12]

Textiles

Furnishing textiles were an important offering of the firm in all its incarnations. By 1883, Morris wrote "Almost all the designs we use for surface decoration, wallpapers, textiles, and the like, I design myself. I have had to learn the theory and to some extent the practice of weaving, dyeing and textile printing: all of which I must admit has given me and still gives me a great deal of enjoyment."[13]

Morris's preference for flat use of line and colour and abhorrence of "realistic" three-dimensional shading was marked; in this he followed medieval conventions. Writing on tapestry weaving, Morris said:

As in all wall-decoration, the first thing to be considered in the designing of Tapestry is the force, purity, and elegance of the silhouette of the objects represented, and nothing vague or indeterminate is admissible. But special excellences can be expected from it. Depth of tone, richness of colour, and exquisite gradation of tints are easily to be obtained in Tapestry; and it also demands that crispness and abundance of beautiful detail which was the especial characteristic of fully developed Mediæval Art. - Of the Revival of Design and Handicraft

It is likely that much of Morris's preference for medieval textiles was formed — or crystallised — during his brief apprenticeship with G. E. Street. Street had co-written a book on Ecclesiastical Embroidery in 1848, and was a staunch advocate of abandoning faddish woolen work on canvas in favour of more expressive embroidery techniques based on Opus Anglicanum, a surface embroidery technique popular in medieval England.[14]

Embroidery

Morris taught himself embroidery, working with wool on a frame custom-built from an old example, and once he had mastered the technique he trained his wife Jane and her sister Bessie Burden and others to execute designs to his specifications. "Embroideries of all kinds" were offered through Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. catalogues, and church embroidery became and would remain an important line of business for its successor companies into the twentieth century.[15] By the 1870s, the firm was offering both designs for embroideries and finished works. Following in Street's footsteps, Morris became active in the growing movement to return originality and mastery of technique to embroidery, and was one of the first designers associated with the Royal School of Art Needlework with its aim to "restore Ornamental Needlework for secular purposes to the high place it once held among decorative arts."[16]

Printed and woven textiles

Morris was producing repeating patterns for wallpaper as early as 1862, and some six years later he designed his first pattern specifically for fabric printing. As in so many other areas that interested him, Morris chose to work with the ancient technique of hand woodblock printing in preference to the roller printing which had almost completely replaced it for commercial uses.

Morris took up the practical art of dyeing as a necessary adjunct of his manufacturing business. He spent much of his time at Staffordshire dye works mastering the processes of that art and making experiments in the revival of old or discovery of new methods. One result of these experiments was to reinstate indigo dyeing as a practical industry and generally to renew the use of those vegetable dyes, like madder, which had been driven almost out of use by the anilines. Dyeing of wools, silks, and cottons was the necessary preliminary to what he had much at heart, the production of woven and printed fabrics of the highest excellence; and the period of incessant work at the dye-vat (1875–76) was followed by a period during which he was absorbed in the production of textiles (1877–78), and more especially in the revival of carpet-weaving as a fine art.[5][17]

Morris's patterns for woven textiles included intricate double-woven furnishing fabrics in which two sets of warps and wefts are interlinked to create complex gradations of colour and texture.[18] His textile designs are still popular today, sometimes recoloured for modern sensibilities, but also in the original colourways.

Tapestry

Morris long dreamed of weaving tapestries in the medieval manner, which he called "the noblest of the weaving arts." In September 1879 he finished his first solo effort, a small piece called "Cabbage and Vine".[19][20] Shortly thereafter Morris trained his employee John Henry Dearle in the technique, setting up a tapestry loom at Queen Square and later a large tapestry works at Merton Abbey.

The Kelmscott Press

In January 1891, Morris founded the Kelmscott Press at Hammersmith, London, in order to produce books by traditional methods, using, as far as possible, the printing technology and typographical style of the fifteenth century. In this he was reflecting the tenets of the Arts and Crafts movement, and responding to the mechanization and mass-production of contemporary book-production methods and to the rise of lithography, particularly those lithographic prints designed to look like woodcuts.

He designed two typefaces based on fifteenth-century models, the Roman "Golden" type (inspired by the type of the early Venetian printer Nicolaus Jenson) and the black letter "Troy" type; a third type, the "Chaucer" was an enlargement of the Troy type. He also designed floriated borders and initials for the books, drawing inspiration from incunabula and their woodcut illustrations. Selection of paper and ink, and concerns for the overall integration of type and decorations on the page, made the Kelmscott Press the most famous of the private presses of the Arts and Crafts movement, and the main inspiration for what became known as the "Private Press Movement". It operated until 1898, producing more than 18,000 copies of 53 different works, comprising 69 volumes, and inspired numerous other private presses, notably the Vale Press, Caradoc Press, Ashendene Press and Doves Press.[21]

Publications

Among the works issued by the Kelmscott Press were:[21][22][23]

- William Morris, The Story of the Glittering Plain (1891)

- William Morris, The Defence of Guenevere and other Poems (1892)

- William Morris, A Dream of John Ball and A King's Lesson (1892)

- Raoul Lafevre, The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye (1892)

- William Shakespeare, The Poems (1893)

- William Morris, News from Nowhere (1893)

- William Caxton (trans.), The History of Reynard the Foxe (1893)

- William Caxton (trans.), The Order of Chivalry (1893)

- Guilelmus, Archbishop of Tyrel, The History of Geoffrey of Boloyne (1893)

- Sir Thomas More, Utopia (1893)

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Sonnets and Lyrical Poems (1893)

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ballads and Narrative Poems (1893)

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Hand and Soul (1894)

- Wilhelm Meinhold, Sidonia the Sorceress (1894)

- William Morris, The Story of the Glittering Plain (1894)

- Algernon Charles Swinburne, Atalanta in Calydon (1894)

- An American Memorial to Keats (1895)

- Sir Percyvelle of Gales (1895)

- William Morris, The Life and Death of Jason (1895)

- Geoffrey Chaucer, The Works (called the Kelmscott Chaucer) (1896)

- William Morris, The Earthly Paradise (1896)

- Sir Ysumbrace (1897)

- William Morris, The Story of Sigurd the Volsung (1898)

The Kelmscott Press edition of The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, with decorations by Morris and illustrations by Burne-Jones, is sometimes counted among the most beautiful books ever produced. Full-scale facsimiles of the Kelmscott Chaucer were published by the Basilisk Press in 1974 and by the Folio Society in 2002. More modest facsimiles were published by World Publishing in 1964 and Omega Books in 1985.

Legacy

Assessment

Three years after his death, Morris's biographer John William Mackail (the husband of Burne-Jones's daughter Margaret and so a member of his immediate circle) summed up his career for the Dictionary of National Biography in a quote that is markedly prescient in its assessment:

The fame of Morris during his life was probably somewhat obscured by the variety of his accomplishments. In all his work after he reached mature life there is a marked absence of extravagance, of display, of superficial cleverness or effectiveness, and an equally marked sense of composition and subordination. Thus his poetry is singularly devoid of striking lines or phrases, and his wall-papers and chintzes only reveal their full excellence by the lastingness of the satisfaction they give. His genius as a pattern-designer is allowed by all qualified judges to have been unequalled. This, if anything, he himself regarded as his specific profession; it was under the designation of "designer" that he enrolled himself in the socialist ranks and claimed a position as one of the working class. And it is the quality of design which, together with a certain fluent ease, distinguishes his work in literature as well as in industrial art. It is yet too early to forecast what permanent place he may hold among English poets. "The Defence of Guenevere" had a deep influence on a very limited audience. With "Jason" and the "Earthly Paradise" he attained a wide popularity: and these poems, appearing as they did at a time when the poetic art in England seemed narrowing into mere labour on a thrice-ploughed field, not only gave a new scope, range, and flexibility to English rhymed verse, but recovered for narrative poetry a place among the foremost kinds of the art. A certain diffuseness of style may seem to be against their permanent life, so far as it is not compensated by a uniform wholesomeness and sweetness which indeed marks all Morris’s work. In "Sigurd the Volsung" Morris appears to have aimed higher than in his other poems, but not to have reached his aim with the same certainty; and his own return afterwards from epic to romance may indicate that the latter was the ground on which he was most at home. The prose romances of his later years have so far proved less popular in themselves than in the dilutions they have suggested to other writers. Here as elsewhere Morris’s great effect was to stimulate the artistic sense and initiate movements. So likewise it was with his political and social work. Much of it was not practical in the ordinary sense; but it was based on principles and directed towards ideals which have had a wide and profound influence over thought and practice.[5]

From a later perspective, Stansky concludes that:

Morris's views on the environment, on preserving what is of value in both the natural and "built" worlds, on decentralising bloated government, are as significant now as they were in Morris's own time, or even more so. Earlier in the twentieth century, much of his thinking, particularly its political side, was dismissed as sheer romanticism. After the Second World War, it appeared that modernisation, centralisation, industrialism, rationalism – all the faceless movements of the time – were in control and would take care of the world. Today, when we have a keen sense of the shambles of their efforts, the suggestions which Morris made in his designs, his writings, his actions and his politics have new power and relevance.[24]

Today, Morris's poetry is little-read. His fantasy romances languished out of print for decades until their rediscovery amid the great fantasy revival of the late 1960s following the phenomenal success of Tolkien's Lord of the Rings. But his textile and wallpaper designs remain a staple of the Arts and Crafts Revival of the turn of the 21st century, and the reproduction of Morris designs as fabric, wrapping paper, and craft kits of all sorts is testament to the enduring appeal of his work. The William Morris Societies in Britain, the US, and Canada are active in preserving Morris's work and ideas.

Notable collections and house museums

A number of galleries and museums house important collections of Morris's work and decorative items commissioned from Morris & Co. The William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow, England, is a public museum devoted to Morris' life, work and influence. There are permanent displays of printed, woven and embroidered fabrics, rugs, carpets, wallpapers, furniture, stained glass and painted tiles by Morris and his associates. In April 2007, The Guardian newspaper reported that funding for the Gallery was threatened by cost cutting by the London borough of Waltham Forest. A campaign to avoid the reduction in opening times and dismissal of key staff is underway.[25] The former "green dining room" at the Victoria and Albert Museum is now its "Morris Room". The V&A's British Galleries house other decorative works by Morris and his associates.[26]

Wightwick Manor in the West Midlands, England, is a notable example of the Morris & Co. style, with original Morris wallpapers and fabrics, De Morgan tiles, and Pre-Raphaelite works of art, managed by the National Trust. Standen in West Sussex, England, was designed by Webb between 1892 and 1894 and decorated with Morris carpets, fabrics and wallpapers. Morris's homes Red House and Kelmscott Manor have been preserved. Red House was acquired by the National Trust in 2003 and is open to the public by advanced reservation. Kelmscott Manor is owned by the Society of Antiquaries of London and is open to the public.

The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California acquired the collection of Morris materials amassed by Sanford and Helen Berger in 1999. The collection includes stained glass, wallpaper, textiles, embroidery, drawings, ceramics, more than 2000 books, original woodblocks, and the complete archives of both Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. and Morris & Co.[27] These materials formed the foundation for the 2002 exhibition William Morris: Creating the Useful and the Beautiful.[28]

Monuments

A fountain located in Bexleyheath town centre, named the Morris Fountain, was created in his honour and unveiled on the anniversary of his birth. Also in Bexleyheath, Morris' home Red House was opened up to the public by the National Trust in 2004. Also, Walthamstow Central tube station has William Morris inspired motifs (by Julia Black) in regularly spaced alcoves along the platform walls.

Literary works

Poetry, fiction, and essays

- The Hollow Land (1856)

- The Defence of Guenevere, and other Poems (1858)

- The Life and Death of Jason (1867)

- The Earthly Paradise (1868–1870)

- Love is Enough, or The Freeing of Pharamond: A Morality (1872)

- The Story of Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of Niblungs (1877)

- Hopes and Fears For Art (1882)

- The Pilgrims of Hope (1885)

- A Dream of John Ball (1888)

- A Tale of the House of the Wolfings, and All the Kindreds of the Mark Written in Prose and in Verse (1889)

- The Roots of the Mountains (1890)

- Poems By the Way (1891)

- News from Nowhere (or, An Epoch of Rest) (1890)

- The Story of the Glittering Plain (1891)

- The Wood Beyond the World (1894)

- Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair (1895)

- The Well at the World's End (1896)

- The Water of the Wondrous Isles (1897)

- The Sundering Flood (1897) (published posthumously)

Translations

- Grettis Saga: The Story of Grettir the Strong with Eiríkr Magnússon (1869)

- The Saga of Gunnlaug the Worm-tongue and Rafn the Skald with Eiríkr Magnússon (1869)

- Völsung Saga: The Story of the Volsungs and Niblungs, with Certain Songs from the Elder Edda with Eiríkr Magnússon (1870) (from the Volsunga saga)

- Three Northern Love Stories, and Other Tales with Eiríkr Magnússon (1875)

- The Odyssey of Homer Done into English Verse (1887)

- The Aeneids of Virgil Done into English (1876)

- Of King Florus and the Fair Jehane (1893)

- The Tale of Beowulf Done out of the Old English Tongue (1895)

- Old French Romances Done into English (1896)

Gallery

Morris & Co. stained glass

-

David's Charge to Solomon (1882), a stained-glass window by Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris in Trinity Church, Boston, Massachusetts.

-

Burne-Jones–designed and Morris & Co.-executed Nativity windows (1882), Trinity Church, Boston

-

Burne-Jones–designed and Morris & Co.-executed The Worship of the Shepherds window (1882), Trinity Church, Boston.

-

Detail from The Worship of the Shepherds window (1882).

Morris & Co. textiles

-

Acanthus wallpaper, 1875

-

Snakeshead printed textile, 1876

-

"Peacock and Dragon" woven wool furnishing fabric, 1878

-

Design for Windrush printed textile, 1881–83

-

Detail of Woodpecker tapestry, 1885

-

The Vision of the Holy Grail tapestry, 1890

-

Acanthus embroidered panel, designed Morris, 1890

-

Strawberry Thief, furnishing fabric, designed Morris, 1883

Decorative objects

-

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, text and decoration by Morris with illustrations by Burne-Jones, 1870s

-

Panel of ceramic tiles designed by Morris and produced by William De Morgan, 1876

Kelmscott Press

-

Kelmscott Press typefaces and colophon, 1897

-

William Morris, publisher

-

The Nature of Gothic by John Ruskin, printed by Kelmscott Press. First page of text, with typical ornamented border

-

Troilus and Criseyde, from the Kelmscott Chaucer. Illustration by Burne-Jones and decorations and typefaces by Morris

See also

- Arts and Crafts movement

- Eco-socialism

- Merry England

- Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

- Social Democratic Federation

- Socialism

- Socialist League

- Victorian decorative arts

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Faulkner, Peter, "The Writer". In Parry, William Morris, p. 44-45

- ^ "The words were written for the old French carol tune shortly before 1860 by Morris, who was in Street's office with Edmund Sedding (architect and compiler of carols, brother of the more famous J. D. Sedding; he died early, in 1868). Sedding had obtained the tune from the organist at Chartres Cathedral, and he published the words and tune in his Antient Christmas Carols, 1860." – The Oxford Book of Carols, 1928, p. 277.

- ^ Set to music by composers including Ralph Vaughan Williams. The Oxford Book of Carols, 1928, p. 406.

- ^ Full text, with illustrations, at "The Life and Death of Jason". Morris Online Edition. 1867. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

DNBwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Faulkner, Peter, "The Writer". In Parry, William Morris, p. 47

- ^ Lin Carter, ed. Kingdoms of Sorcery, p. 39 Doubleday and Company Garden City, NY, 1976.

- ^ L. Sprague de Camp, Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy, p. 46. ISBN 0-87054-076-9

- ^ L. Sprague de Camp, Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers, p. 40.

- ^ L. Sprague de Camp, Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers, p. 26.

- ^ Hammond and Scull, The J. R. R. Tolkien Companion and Guide, p. 816.

- ^ Hero, Stephen, "Morris and James Joyce," The Journal of William Morris Studies, 6.3 (Summer 1985): 36, p. 11.

- ^ Quoted in Waggoner, DianeThe Beauty of Life: William Morris & the Art of Design.

- ^ Parry, William Morris Textiles, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Parry, William Morris Textiles, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Quoted in Parry, William Morris Textiles, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Parry, William Morris Textiles, pp. 36–46.

- ^ Waggoner, The Beauty of Life, p. 54.

- ^ Parry, William Morris Textiles, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Waggoner, The Beauty of Life, p. 86.

- ^ a b Fiell and Fiell (1999), William Morris pp. 160–165.

- ^ Dreyfus, John, "The Kelmscott Press". In Parry, William Morris (1996) pp. 310–345.

- ^ "William Morris and the Kelmscott Press". Retrieved 2008-08-22. See also Peterson.

- ^ Stansky (1983) p. 89.

- ^

"News from Waltham Forest". The Guardian. 2007-04-21.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "William Morris at the Victoria and Albert Museum". Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ "Crafts Cornered", Los Angeles Times, 15 December 1999, p. F1.

- ^ "Huntington Library: "William Morris: Creating the Useful and the Beautiful"". Retrieved 2008-08-22.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

This article also incorporates text from the Dictionary of National Biography, supplemental volume 3 (1901), a publication now in the public domain.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, Tolkien: A Biography, New York, Ballantine Books, 1977, ISBN 0-04-928037-6

- Coote, Stephen, William Morris: His Life and Work, Smithmark Publishers, 1995, ISBN 1-85833-479-9

- Daly, Gay, Pre-Raphaelites in Love, New York, Ticknor & Fields, 1989, ISBN 0899194508

- de Camp, L. Sprague, Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy, ISBN 0-87054-076-9

- Fairclough, Oliver and Emmeline Leary, Textiles by William Morris and Morris & Co. 1861–1940, Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, 1981, ISBN 0-89860-065-0

- Fiell, Charlotte and Peter, William Morris Cologne, Taschen, 1999 ISBN 3822866172.

- Hammond, Wayne and Christina Scull, The J. R. R. Tolkien Companion and Guide, Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 2006, ISBN 978-0618391134

- Kelvin Norman ed. The Collected Letters of William Morris Princeton University Press 1985 ISBN 978 069 1065014

- Mackail, J. W., The Life of William Morris in two volumes, London, New York and Bombay: Longmans, Green and Co., 1899

- Google Books edition of Volume I and Volume II (1911 reprint) retrieved 16 August 2008

- Mackail, J. W., "William Morris," in The Dictionary of National Biography. Supp. vol. 3 (London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1901), p. 197–203, reproduced at the William Morris Society

- Parry, Linda, "Textiles", in The Earthly Paradise: Arts and Crafts by Wiliam Morris and his Circle in Canadian Collections, edited by Katharine A. Lochnan, Douglas E. Schoenherr, and Carole Silver, Key Porter Books, 1993, ISBN 1-55013-450-7

- Parry, Linda, ed., William Morris, Abrams, 1996, ISBN 0-8109-4282-8

- Parry, Linda, William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement: A Sourcebook, New York, Portland House, 1989 ISBN 0-517-69260-0

- Parry, Linda, William Morris Textiles, New York, Viking Press, 1983, ISBN 0-670-77074-4

- Parry, Linda, Textiles of the Arts & Crafts Movement, Thames and Hudson, revised edition 2005, ISBN 0-500-28536-5

- Stansky, Peter (1983). William Morris. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019287571X.

- Peterson, William S., A bibliography of the Kelmscott Press. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984. ISBN 0-198-18199-x

- Peterson, William S., The Kelmscott Press: a history of William Morris's typographical adventure. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991. ISBN 0-198-12887-8

- Thompson, E.P. (2nd edition, 1976) William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary, Pantheon, ISBN 0-394-73320-7

- Todd, Pamela, Pre-Raphaelites at Home, New York: Watson-Guptill, 2001. ISBN 0823042855

- Waggoner, Diane, The Beauty of Life: William Morris & the Art of Design, Thames and Hudson, 2003, ISBN 0-500-28434-2

Further reading

- Arscott, Caroline. William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones: Interlacings, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press (Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art), 2008). ISBN 978-0-300-14093-4

- Freudenheim, Leslie. Building with Nature: Inspiration for the Arts & Crafts Home (Gibbs Smith 2005 ) ISBN 9781586854638.

- Goodway, David. Anarchist Seeds beneath the Snow: Left Libertarian Thought and English Writers From William Morris to Colin Ward (2006).

- MacCarthy, Fiona (1994). William Morris: A Life For Our Time. London: Faber. ISBN 0571174957.

- Marsh, Jan (2005). William Morris and Red House: A Collaboration Between Architect and Owner. National Trust Books. ISBN 9781905400010.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Pinkney, Tony. William Morris in Oxford: The Campaigning Years, 1879–1895 (2007).

- Robinson, Duncan (1982). William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and the Kelmscott Chaucer. London: Gordon Fraser.

- Watkinson, Ray (1990). William Morris as Designer. London: Trefoil Books. ISBN 0862940400.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

Sources

- Works by William Morris at Project Gutenberg. Plain text and HTML versions.

- Works by William Morris at Internet Archive. Scanned books, many illustrated.

- Works by William Morris at The Online Books Page.

- Works by William Morris at sacred-texts.com, including full text of The Earthly Paradise.

- William Morris Index Entry at Poets' Corner

- The William Morris Internet Archive (marxists.org)

- Biography by J. W. Mackail (Dictionary of National Biography, 1901)

- "William Morris", Stephen Gwynn in Macmillan's Magazine, Vol. LXXVIII, May to Oct., 1898, pp. 153-160

Other

- William Morris and his Circle

- William Morris Stained Glass

- William Morris at Art Passions

- William Morris - The Soul of Arts and Crafts

- The William Morris Gallery (London Borough of Waltham Forest)

- The William Morris Society

- A Morris and De Morgan tile panel at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- The Pre-Raph Pack Discover more about the artists, the techniques they used and a timeline spanning 100 years.

- William Morris online exhibition at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- 1834 births

- 1896 deaths

- Artists' Rifles soldiers

- Alumni of Exeter College, Oxford

- Arts and Crafts Movement artists

- British graphic designers

- British Marxists

- Communalism

- English architects

- English designers

- English fantasy writers

- English poets

- English printers

- English socialists

- Libertarian socialists

- Marxist writers

- Mythopoeic writers

- Old Marlburians

- People from Walthamstow

- Social Democratic Federation members

- Socialist League (UK, 1885) members

- Textile designers

- Typographers

- Victorian poetry