Silver Age of Comic Books

| Silver Age of Comic Books | |

|---|---|

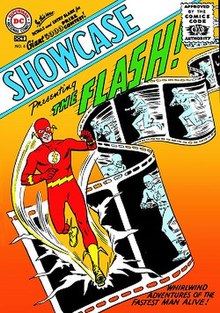

Showcase #4 (October 1956), generally considered the start of the Silver Age. Cover art by Carmine Infantino & Joe Kubert | |

| Time span | 1956 – late 1960s/early 1970s |

| Related periods | |

| Preceded by | Golden Age of Comic Books |

| Followed by | Bronze Age of Comic Books |

The Silver Age of Comic Books was a period of artistic advancement and commercial success in mainstream American comic books, predominantly those in the superhero genre. Following the Golden Age of Comic Books and the interregnum of the Atomic Age, the Silver Age is considered to cover the period from 1956 to around 1970, and was succeeded by the Bronze and Modern Ages.[1] A number of important comics writers and artists contributed to the era, including writers Stan Lee, Gardner Fox, Edmond Hamilton, John Broome, and Robert Kanigher, and artists Jack Kirby, Gil Kane, Steve Ditko, Mike Sekowsky, Carmine Infantino, Curt Swan, John Buscema, and John Romita, Sr. By the end of the Silver Age, a new generation of talent had entered the field, including writers Denny O'Neill, Mike Friedrich, Roy Thomas, and Archie Goodwin, and artists such as Neal Adams, Jim Steranko, and Barry Windsor-Smith.

Blamed for a rise in juvenile crime, the popularity of superhero comics declined following the Second World War. However, the 1954 implementation of the Comics Code Authority to regulate comic content sparked a resurgence in the genre that began with the introduction of a new version of DC Comics's The Flash in Showcase #4 (October 1956). In response to strong demand, DC began publishing more superhero titles, prompting Marvel Comics to follow suit beginning with Fantastic Four #1. Silver Age comics have become collectible; as of 2008 the most sought-after comic of the era is Spider-Man's debut in Amazing Fantasy #15.

An important feature of the period was the evolution of the character makeup of superheroes. Science fiction and aliens replaced gods and magic.[2] DC Comics sparked the superhero's revival with its publications from 1955 to 1960. Marvel Comics then capitalized on the revived interest in superhero storytelling with sophisticated stories and characterization.[3] In contrast to previous eras, Silver Age characters were "flawed and self-doubting".[4] Young children and girls were targeted during the Silver Age by certain publishers; in particular, Harvey Comics attracted this group with titles such as Little Dot. Adult oriented underground comics also began during the Silver Age. There are several suggested endpoints for the Silver Age, including changes in the Green Lantern series and the death of Spider-Man's girlfriend in a 1973 issue (#121) of Amazing Spider-Man.

Origin of the term

Comics historian and movie producer Michael Uslan traces the origin of the "Silver Age" term to the letters column of Justice League of America #42 (February 1966), which went on sale December 9, 1965.[5] Letter-writer Scott Taylor of Westport, Connecticut wrote, "If you guys keep bringing back the heroes from the [1930s-1940s] Golden Age, people 20 years from now will be calling this decade the Silver Sixties!"[5] According to Uslan, the natural hierarchy of gold-silver-bronze, as in Olympic medals, took hold. "Fans immediately glommed onto this, refining it more directly into a Silver Age version of the Golden Age. Very soon, it was in our vernacular, replacing such expressions as ... 'Second Heroic Age of Comics' or 'The Modern Age' of comics. It wasn't long before dealers were ... specifying it was a Golden Age comic for sale or a Silver Age comic for sale".[5]

History

Background

Spanning World War II, when comics provided cheap and disposable escapist entertainment that could be read and then discarded by the troops,[6] the Golden Age of comic books covered the late 1930s to the late 1940s. A number of major superheroes were created during this period, including Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and Captain America.[7] The brief so-called Atomic Age followed, between 1945 and 1956,[8] but in subsequent years comics were blamed for a rise in juvenile crime statistics, although this rise was shown to be in direct proportion to population growth.[6] When juvenile offenders admitted to reading comics, it was seized on as a common denominator;[6] one notable critic was Fredric Wertham, author of the book Seduction of the Innocent (1954),[6] who attempted to shift the blame for juvenile delinquency from the parents of the children to the comic books they read. The result was a decline in the comics industry.[6] To address public concerns, in 1954 the Comics Code Authority was created to regulate and curb violence in comics, marking the start of a new era.[9]

DC Comics

The Silver Age began with the publication of DC Comics's Showcase #4 (October 1956), which introduced the modern version of the Flash.[10][11] At the time, only three superheroes—Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman—were still published under their own titles.[12] According to DC comics writer Will Jacobs, Superman was available in "great quantity, but little quality."[12] Batman was doing better, but his comics were "lackluster" in comparison to his earlier "atmospheric adventures" of the 1940s,[12] and Wonder Woman, having lost her original writer and artist, was no longer "idiosyncratic" or "interesting."[12] Jacobs describes the arrival of Showcase #4 on the newsstands as "begging to be bought";[12] the cover featured an undulating film strip depicting the Flash running so fast that he had escaped from the frame.[12] Editor Julius Schwartz, writer Gardner Fox and artist Carmine Infantino were behind the Flash's revitalization.[13]

With the success of Showcase #4, several other 1940s superheroes were reworked during Schwartz's tenure, including Green Lantern, The Atom, and Hawkman,[14] as well as the Justice League of America.[13] The DC artists responsible included Murphy Anderson, Gil Kane and Joe Kubert.[13] Only the characters' names remained the same; their costumes, locales, and identities were altered, and imaginative scientific explanations for their superpowers generally took the place of magic as a modus operandi in their stories.[14] Schwartz, a lifelong science fiction fan, was the inspiration for the re-imagined Green Lantern[15]—the Golden Age character, railroad engineer Alan Scott, possessed a ring powered by a magical lantern,[15] but his Silver Age replacement, test pilot Hal Jordan, had a ring powered by an alien battery and created by an intergalactic police force.[15]

Until the mid-1950s, DC's characters were depicted as living on alternate Earths. Prior to the Silver Age their home was Earth-Two, whereas the Silver Age stars lived on Earth-One.[16] Writers later decided that the two realities were separated by a vibrational field which could be crossed, should a storyline require that superheroes from different worlds team up.[16]

Although the Flash is generally regarded as the first superhero of the Silver Age, the introduction of the Martian Manhunter in Detective Comics #225 predates Showcase #4 by almost a year, and some historians consider this character the first Silver Age superhero.[17] However, comics historian Craig Shutt, author of the Comics Buyer's Guide column "Ask Mister Silver Age", disagrees.[18] Shutt notes that when the Martian Manhunter debuted, he was a detective who used his alien abilities to solve crimes. Although he did ultimately become a charter member of the Justice League of America, originally he was just a "quirky detective", like other contemporaneous DC characters who were "TV detectives, Indian detectives, supernatural detectives, [and] animal detectives."[18] Schutt feels the Martian Manhunter only became a superhero in Detective Comics #273 (November 1959), when he received a secret identity and other superhero accoutrements.[18] Said Schutt, "Had Flash not come along, I doubt that the Martian Manhunter would've led the charge from his backup position in Detective to a new super-hero age."[18] Another hero that predates Showcase #4 is Captain Comet, who debuted in Strange Adventures #9 (June 1951). Comic Book Resources columnist Steven Grant considers him to be the first Silver Age superhero.[19]

Marvel Comics

DC added to their momentum with their 1960 introduction of the Justice League of America, an all-star group consisting of their most popular characters. Aware of the Justice League's strong sales, Timely and Atlas publisher Martin Goodman, a publishing trend-follower,note 1 directed his comics editor Stan Lee to create a comic-book series about a team of superheroes.[20] Lee recalled in 1974 that "Martin mentioned that he had noticed one of the titles published by National Comics seemed to be selling better than most. It was a book called The [sic] Justice League of America and it was composed of a team of superheroes. ... ' If the Justice League is selling ', spoke he, ' why don't we put out a comic book that features a team of superheroes?'"[20] Marvel Comics's Fantastic Four was the result.[20]

Under the guidance of writer-editor Stan Lee and artists/co-writers such as Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, Marvel began its own rise to prominence.[12] Introducing dynamic plotting and more sophisticated characterization into superhero comics, Marvel began targeting teen and college-aged readers in addition to the children's market.[12] Based on the success of The Fantastic Four, Lee and his artists created eleven new series over the next two-and-a-half years,[12] with Spider-Man and, after a slow start, the Hulk among the most popular new characters.[21] Other significant and enduring Marvel Silver Age heroes include Iron Man, Thor, Daredevil, the X-Men, and Marvel's own all-star group, the Avengers.[22] Captain America, a hero from the Golden Age, was revived in Avengers #4 (March 1964).[22]

IGN columnist and comic historian Peter Sanderson compares the 1960s DC to a large Hollywood studio.[23] Having reinvented the superhero genre, by the latter part of the decade he believes DC was suffering from a creative drought.[23] The audience for comics was no longer just children, and Sanderson sees the 1960s Marvel as the comic equivalent of the French New Wave, developing new methods of storytelling that drew in and retained readers who were in their teens and older and thus influencing the comics writers and artists of the future.[23] Comics historian Craig Shutt compares DC's and Marvel's differing styles: according to Schutt, DC heroes were straightforward in their dealings with each other, quickly banding together to defeat an enemy.[24] In contrast Marvel's heroes trusted each other less, and would frequently oppose each other before resolving their differences and joining against a common foe.[24] DC's approach settled conflicts between heroes without violence; Marvel's "addressed the age-old, little-kid question of which hero would win in a fight".[24]

Other publishers

One of the top comics publishers in 1956, Harvey Comics discontinued their horror comics when the comics code was implemented and sought a new target audience.[25] Their focus shifted to children from six to twelve years of age, especially girls, with characters such as Richie Rich, Casper the Friendly Ghost, and Little Dot.[25] Many of their comics featured young girls who "defied stereotypes and sent a message of acceptance of those who are different."[25] Other publishers, such as Dell Comics and Gold Key Comics, made similar changes.[25] Although their characters have inspired a number of nostalgic movies and ranges of merchandise, Harvey comics of the period are not as sought after in the collectors' market as DC and Marvel titles.[25]

The success of DC's and Marvel's Silver Age titles led Archie Comics to launch their own superheroes.[26] The Archie Adventure line (subsequently retitled Mighty Comics) included The Fly, The Jaguar, and The Shield, a revamped Golden Age character.[26] The success of The Avengers and the Justice League of America prompted Archie Comics to create their own superhero team, The Mighty Crusaders, which saw The Comet and Flygirl join with three characters with their own titles.[26] The Archie series mixed typical superhero fare with the 1960s' Batman television series style camp.[26]

According to John Strausbaugh of The New York Times, traditional comic book historians feel that although the Golden Age deserves study, the only noteworthy aspect of the Silver Age was the advent of underground comics.[7] One commentator has suggested that underground comics are considered legitimate art because they were typically written and drawn by a single person;[27] artists like Robert Crumb and Gilbert Shelton produced comics described as raw and instinctual.[28] While most comics of the era were pure fantasy, underground comics targeted adults and reflected the counterculture movement of the time,[29][30] being printed by ad-hoc publishers and distributed in head shops.[28]

End

Various events have been identified as marking the end of the Silver Age. One suggestion has been the 1969 publication of the last 12 cent comics,[31] while others have focused on the publishers that were its driving forces: Marvel and DC. According to Will Jacobs, the Silver Age ended in April 1970 when the man who had started it, Julius Schwartz, handed over Green Lantern to Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams in response to reduced sales.[32] John Strausbaugh also connects the end of the Silver Age to Green Lantern. He observes that in 1960, the character embodied the can-do optimism of the era, declaring "No one in the world suspects that at a moment's notice I can become mighty Green Lantern – with my amazing power ring and invincible green beam! Golly, what a feeling it is!"[7] However, by 1972 Green Lantern had become world weary; "Those days are gone – gone forever – the days I was confident, certain ... I was so young ... so sure I couldn't make a mistake! Young and cocky, that was Green Lantern. Well, I've changed. I'm older now ... maybe wiser, too ... and a lot less happy."[7] Strausbaugh writes that the Silver Age "went out with that whimper."[7] Comics scholar Arnold T. Blumberg places the end of the Silver Age in June 1973, when Spider-Man's girlfriend Gwen Stacy was killed in the two part story The Night Gwen Stacy Died. According to Blumberg, the era of "innocence" was ended by 'the "snap" heard round the comic book world - the startling, sickening snap of bone that heralded the death of Gwen Stacy.'[33]

Aftermath and legacy

The Silver Age of comic books was followed by the Bronze Age.[34] The cause of the shift is not clearly defined, but there are a number of possibilities.[34] Scott, of Comic Book Resources, lists several commonly cited reasons including changes in personnel and the publication of individual comics. Among the latter are Conan #1 (1970) and Green Lantern/Green Arrow #76 (April 1970), "often cited as the first books of the Bronze Age."[34] He also notes Jack Kirby’s move from Marvel to DC in 1970, and Mort Weisinger's retirement that same year.[34] Another possible candidate is the return of horror comics and stories with increased social relevancy.[35] Arnold T. Blumberg has argued that the shift was a gradual process that lasted from the late 1960s until 1973, ending with the death of Gwen Stacy—an "event that many name as the single most memorable moving moment in collective fan recall".[36] He writes that there was a willingness by creators and publishers to tackle more mature themes, even if they "were filtered through the somewhat simplistic lens of the superhero", thus bringing an end to "the light-hearted, carefree Silver Age".[36]

According to Peter Sanderson, the "neo-silver movement", which began in 1986 with Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? by Alan Moore and Curt Swan, was a backlash against the Bronze Age with a return to Silver Age principles.[37] In Sanderson's opinion, each comics generation rebels against the previous, and the movement was a response to Crisis on Infinite Earths, which itself was an attack on the Silver Age.[37] Neo-silver comics creators made comics that recognized and assimilated the more sophisticated aspects of the Silver Age.[37]

Artists

Arlen Schumer, author of "The Silver Age of Comic Book Art", singles out Carmine Infantino's Flash as the embodiment of the design of the era: "as sleek and streamlined as the fins Detroit was sporting on all its models."[7] Other notable artists of the era include Gene Colan, Steve Ditko, Gil Kane, Jack Kirby, Joe Kubert, and Curt Swan.[38]

Two artists that changed the comics industry dramatically in the late 1960s were Neal Adams and Jim Steranko. Adams's breakthrough was based on layout and rendering.[39] According to R.C. Baker of the Village Voice, Neal Adams is one of the country's greatest draftsmen.[40] Best known for returning Batman to his somber roots after the campy success of the Batman television show,[40] his realistic depictions of anatomy, faces, and gestures changed comics' style in a way that Strausbaugh sees reflected in modern graphic novels.[7]

One of the few writer-artists at the time, Steranko's forte involved making use of a cinematic style of storytelling.[39] Strausbaugh credits him as one of Marvel's strongest creative forces during the late 1960s, his art owing a large debt to Salvador Dalí.[7] Steranko started by inking and penciling the details of Kirby's artwork on Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. beginning in Strange Tales #135, but by Strange Tales #155 Stan Lee had put him in charge of both writing and drawing Fury's adventures.[41] He exaggerated the James Bond-style spy stories, introducing the Vortex Beam (which lifts objects), the aphonic bomb (which explodes silently), a miniature Electronic Absorber (which protected Fury from electricity), and the Q-Ray machine (a molecular disintegrator)—all in his first eleven-page story.[41]

Top 20 comics

As of 2008, the collecting of Silver Age comics was on the rise. Possible reasons for this are that certain Golden Age comics are becoming too expensive or that baby boomers fondly remember the comics from their youth.[42] Amazing Fantasy #15, the first appearance of Spider-Man, is considered the "holy grail" of Silver Age comics.[43] According to "The Official Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide #38" by Robert Overstreet, the following twenty comics were the most sought after by collectors.[44]

| Title | Issue | Publisher | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amazing Fantasy | 15 | Marvel | First appearance of Spider-Man |

| Showcase | 4 | DC Comics | First appearance of Barry Allen as the Flash |

| Fantastic Four | 1 | Marvel | First appearance of the Fantastic Four |

| Amazing Spider-Man | 1 | Marvel | Spider-Man gets his own series |

| Hulk | 1 | Marvel | First appearance of Hulk |

| X-Men | 1 | Marvel | First appearance of X-Men |

| Showcase | 8 | DC Comics | Second Silver Age appearance of the Flash |

| Journey Into Mystery | 83 | Marvel | First appearance of Thor |

| Showcase | 9 | DC Comics | Lois Lane stars in her own adventure |

| The Flash | 105 | DC Comics | First Flash comic book since Flash Comics was cancelled with issue #104 |

| Tales of Suspense | 39 | Marvel | First appearance of Iron Man |

| Brave and the Bold | 28 | DC Comics | First appearance of the Justice League of America |

| Adventure Comics | 247 | DC Comics | Superboy meets the Legion of Super-Heroes |

| Justice League of America | 1 | DC Comics | First Issue |

| Showcase | 22 | DC Comics | First appearance of Silver Age Green Lantern |

| Fantastic Four | 5 | Marvel | First appearance of Dr. Doom |

| Tales to Astonish | 27 | Marvel | First appearance of Hank Pym |

| Fantastic Four | 2 | Marvel | Second appearance of the Fantastic Four, first appearance of the Skrulls |

| Green Lantern | 1 | DC Comics | First issue |

| Amazing Spider-Man | 2 | Marvel | First appearance of the Vulture |

| Action Comics | 252 | DC Comics | First appearance of Kara "Supergirl" Zor-El |

See also

Footnotes

^ Apocryphal legend has it that in 1961, Timely and Atlas publisher Martin Goodman was playing golf with either Jack Liebowitz or Irwin Donenfeld of rival DC Comics (then known as National Periodical Publications), who bragged about DC's success with the Justice League, which had debuted in The Brave and the Bold #28 (February 1960) before going on to its own title.[45]

Film producer and comics historian Michael Uslan later contradicted some specifics, while supporting the story's framework:

Irwin said he never played golf with Goodman, so the story is untrue. I heard this story more than a couple of times while sitting in the lunchroom at DC's 909 Third Avenue and 75 Rockefeller Plaza office as [Sol Harrison and [production chief] Jack Adler were schmoozing with some of us ... who worked for DC during our college summers.... [T]he way I heard the story from Sol was that Goodman was playing with one of the heads of Independent News, not DC Comics (though DC owned Independent News). ... As the distributor of DC Comics, this man certainly knew all the sales figures and was in the best position to tell this tidbit to Goodman. ... Of course, Goodman would want to be playing golf with this fellow and be in his good graces. ... Sol worked closely with Independent News' top management over the decades and would have gotten this story straight from the horse's mouth.[46]

Notes

- ^ Reynolds, Richard. Super Heroes: A Modern Mythology (1994), University Press of Mississippi p.8-9. ISBN 0878056947

- ^ Callahan, Timothy (2008-08-06). "In Defense of Superhero Comics". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ St.Louis, Hervé (October 9, 2005). "Is DC Comics Spearheading a New Age in Super Hero Comics?". Comic Book Bin. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ Reif, Rita (October 27, 1991). "ANTIQUES; Collectors Read the Bottom Lines of Vintage Comic Books". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ^ a b c Alter Ego vol. 3, #54 (November 2005), p. 79

- ^ a b c d e Mooney, Joe (April 19, 1987). "It's No Joke: Comic Books May Help Kids Learn to Read". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Strausbaugh, John (December 14, 2003). "ART; 60's Comics: Gloomy, Seedy, and Superior". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ^ Over street, Robert M. Official Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide 38th Edition New York:2008 (Glossary Pages—1026-1031) Page 1026

- ^ "In graphic terms..." The San Diego Union-Tribune. July 17, 2006. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ CBR News Team (July 2, 2007). "DC Flashback: The Flash". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ^ Zicari, Anthony (August 3, 2007). "Breaking the Border - Rants and Ramblings". Comics Bulletin. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jacobs, pp. 3-4Jacobs 1985 Cite error: The named reference "Jacobs34" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Nash, Eric (February 12, 2004). "Julius Schwartz, 88, Editor Who Revived Superhero Genre in Comic Books". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ a b Pethokoukis, James (February 26, 2004). "Flash Facts". U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ^ a b c Janulewicz, Tom (1 February 2000). "Gil Kane, Space-Age Comic Book Artist, Dies". Space.com. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ^ a b Singer, Matt (June 27, 2006). "Superfan Returns". Village Voice. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ Shaw, Scott (September 22, 2003). "Oddball Comics". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on 2003-10-20. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- ^ a b c d Shutt, Craig. Baby Boomer Comics: The Wild, Wacky, Wonderful Comic Books of the 1960s!(Krause Publications, Iola, Wisconsin, 2003), P. 21. ISBN 0-87349-688-X

- ^ Grant, Steven (February 18, 2004). "Permanent Damage". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ^ a b c Stan Lee, Origins of Marvel Comics (Simon and Schuster/Fireside Books, 1974), p. 16

- ^ Mark, Norman. "The New Super-Hero Is a Pretty Kinky Guy". Eye Magazine, Hearst Corporation, vol. 2, #2 (February 1969). Reprinted in Alter Ego #74 (December 2007), pp. 16-25

- ^ a b O'Neil, Keith (September 27, 2007). "The history of comics". Keene Equinox. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ^ a b c Sanderson, Peter (October 10, 2003). "Comics in Context #14: Continuity/Discontinuity". IGN. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ^ a b c O'Shea, Tim (February 2, 2004). "Fun with Mr. Silver Age: Craig Shutt". Comics Bulletin. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ^ a b c d e Jackson, Kathy Merlock (2007). "Baby-Boom Children and Harvey Comics After the Code: A Neighborhood of Little Girls and Boys". ImageText. University of Florida.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Weiland, Jonah (July 15th, 2003). "'The Mighty Crusaders: Origin of a Super-Team' ships November". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ault, Donald (2004). "Preludium: Crumb, Barks, and Noomin: Re-Considering the Aesthetics of Underground Comics". ImageText. University of Florida.

- ^ a b Heer, Jeet (September 28, 2003). "Free Mickey!". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ Keys, Lisa (April 11, 2003). "Drawing Peace In the Middle East". The Forward. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ^ Wood, Beth (July 17, 2006). "In graphic terms..." The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Radfored, Bill (April 26, 2000). "May to see return to Silver Age of comics". The Gazette. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ^ Jacobs, p. 154Jacobs 1985

- ^ Blumberg, Arnold T. (Fall 2003). ""'The Night Gwen Stacy Died:' The End of Innocence and the Birth of the Bronze Age"". Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture. ISSN 1547-4348. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ^ a b c d Scott (September 16, 2008). "Scott's Classic Comics Corner: A New End to the Silver Age Pt. 1". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ Scott (September 18, 2008). "Scott's Classic Comics Corner: A New End to the Silver Age Pt. 3". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ a b Blumberg, Arnold T. (2003). "'The Night Gwen Stacy Died:' The End of Innocence and the Birth of the Bronze Age". Reconstruction. 3 (4). Retrieved 2008-11-14.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Sanderson, Peter (2004). "Comics in Context #33: A Boatload of Monsters and Miracles". IGN. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ "Superb record of the superheroes' silver age". Canberra Times. January 17, 2004. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ^ a b Grant, Steven (April 5, 2000). "Master of the Obvious 4-5-2000". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ a b Baker, R.C. (November 18, 2003). "America Gods". Village Voice. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Jacobs, p. 144Jacobs 1985

- ^ "Silver Age Drives Weekly Heritage Auction". DiamondGalleries.com. August 20, 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ^ "Amazing Fantasy #15 CGC 8.5 in ComicLink February/March Featured Auction". DiamondGalleries.com. January 22, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ^ Overstreet, Robert (2008). The Official Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide #38. New York: Random House. p. 154. ISBN 0375722394.

- ^ Sinclair, Tom (June 20, 2003). "Still a Marvel!". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- ^ Michael Uslan letter published in Alter Ego #43 (December 2004), pp. 43-44

References

- ^ , Jacobs, Will (1985). The Comic Book Heroes: From the Silver Age to the Present. New York, New York: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 0517554402.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)