Era of Stagnation

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2009) |

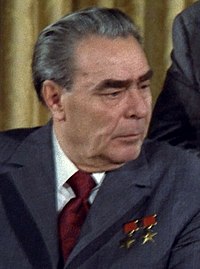

Period of stagnation, also known as Brezhnevian Stagnation (or Brezhnev stagnation), the Stagnation Period, or the Era of Stagnation, refers to a period of economic stagnation under Leonid Brezhnev in the history of the Soviet Union that started in the mid-1970s.

Terminology

Various authors suggest various definitions of the epoch of stagnation, but generally, it refers to the period while Brezhnev was general secretary, also including, perhaps, the short administrations of Andropov and Chernenko, i.e., approximately from 1965 until 1985, or sometimes even through much of the term of Gorbachev, i.e. approximately from 1965 through the end of 1989.[1][2]

The beginning of this stagnation was marked with the Sinyavsky-Daniel trial and suppression of the Prague Spring; these are most known events which indicated that neither discussion nor serious reforms (even within the traditional Soviet paradigm) would be allowed during that period. During that period, any serious critics of communism, communist leaders, Soviet literature, or even typical Soviet events were qualifed as anti-Soviet propaganda.

Brezhnev himself declared his time as the period of Developed Socialism, proclaimed constructed in the 1977 Soviet Constitution: The developed Socialist society (развитое социалистическое общество) is a natural, logical stage on the road to Communism. The same constitution stated the leading role of the Communist Party.[3]

Stagnation was characterized by suppression of both growth in the economy and any social life of the country, as well as repression of dissidents.

Economy

In the economy, a sharp reduction of economic growth was observed, in both Soviet and Western statistics. The Soviet Union's foreign trade and imports, once a small part of the economy, was now of great importance, which made détente a top priority. However the economics of the country were not really weak at that time: it was capable of affording the Mir space station, Tu-144 supersonic plane, Buran Space Shuttle-like spacecraft, Baikal Amur Mainline, N1 Moon rocket and other very expensive projects. Some of these are criticized as underfunded or badly planned.

However it seems that the central governmental control had difficulties in balancing the consumer market, and some goods from time to time simply disappeared from the shops. It was either required to spend a lot of time in queues or travel somewhere where the needed goods were still available. Accumulating and reselling them was a profitable but illegal business. In many cases lack of some goods is difficult to explain by low economic potential or governmental decisions: for instance, the flat 4.5 V 3R12 battery was difficult to get while the similar round [[::File:Fotothek df roe-neg 0006335 017 Batterie von Pertrix.jpg|1.5 V LR20]] battery was available without problems. The unexpected lack of various goods was recognized by the government and called "deficit". The official view was that it was a transient problem, one that could be solved in the near future

As the circulation of the work force could not be balanced by salaries, there was a lack of workers in some areas, largely in the agricultural sector. This was attempted to be solved by forcing older pupils, students and in some cases even soldiers to work for some limited time as agricultural workers.

Opposition

On the other hand, Soviet society became static. Post-Stalinist reforms initiated under Nikita Khrushchev were discontinued. Not all the people accepted the ideology of stagnation. Non-loyalty was punished. Any non-authorised meetings and demonstrations were suppressed. [4]. Dissidents were routinely arrested [5] [6]. The supporters claimed that these arrests were illegal, because there is no criminality in the realization of the human right to obtain and distribute information; this right was declared in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) [7] and the final act of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (1975) [8]

Art and science

Many writers[who?] did not mention the stagnation and repressions. Later, during the introduction of glasnost, they pretended that they did not know about repressions of citizens, who did not support the Brezhnev stagnation[9]. From the other side, artists propagating "Soviet values" formed a well paid, elite group that enjoyed an easy life and high social status. The requirements for art (generalized under name of Socialist realism) were not as rude and straightforward as during Stalinism but still well above that any true artist would understand as acceptable.

Scientific fields such as genetics and computer science that were officially forbidden during Stalinism[citation needed] were no longer repressed. The most of remaining pressure concentrated on historical and social sciences, However, history and social sciences material were usually written in a theme that was in tune with Soviet ideology. In particular, the departments of Scientific Communism and Scientific Atheism were mandatory in many universities[citation needed].

The overall level of science varied[citation needed] but in some cases was at the same level with the rest of the world; for instance, Dubnium was discovered by Soviet scientists at the Dubna research center. However, the science level was not balanced between directions, with some topics (such as advanced electronics) being much less advanced than nuclear physics.

The stagnation effectively continued under Brezhnev's successors, Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, until perestroika was initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1986.

See also

References

- ^

Khazanov, Anatoly M. (1992). "Soviet Social Thought in the Period of Stagnation". Philosophy of the Social Sciences. 22 (2). SAGE Publications: 231–237. doi:10.1177/004839319202200205.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Grant, Ted (2006-09-22). "Russia, from Revolution to Counter-Revolution". In defence of Marxism (Part 6).

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^

Soviet Union (Former~) - Constitution, {Adopted on: 7 Oct 1977 }

CONSTITUTION (FUNDAMENTAL LAW) OF THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS

CONSTITUTION OF THE USSR (1977) CONSTITUTION (FUNDAMENTAL LAW) OF THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS Adopted at the Seventh (Special) Session of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, Ninth Convocation, On October 7, 1977 Novosti Press Agency Publishing House Moscow, 1985 - ^ Хроника Текущих Событий: выпуск 3

- ^ Хроника Текущих Событий: выпуск 4

- ^ Letter by Andropov to the Central Committee (10 July 1970), (English translation).

- ^ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, resolution 217 A (III), accepted 10 Dec. 1948.

- ^ CONFERENCE ON SECURITY AND CO-OPERATION IN EUROPE FINAL ACT Helsinki, 1 Aug. 1975.

- ^ Sofia Kallistratova. We were not silent! - open letter to writer Chingiz Aitmatov, in Russian. С. В. Калистратова. Открытое письмо писателю Чингизу Айтматову, 5 мая 1988 г.