The Secret of Monkey Island

| The Secret of Monkey Island | |

|---|---|

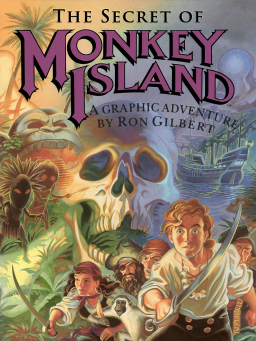

The game's cover art was produced by Steve Purcell | |

| Developer(s) | Lucasfilm Games |

| Publisher(s) | Lucasfilm Games |

| Designer(s) | Ron Gilbert Tim Schafer Dave Grossman |

| Composer(s) | Barney Jones Michael Land Patric Mundy Andy Newell |

| Series | Monkey Island |

| Engine | SCUMM |

| Platform(s) | Amiga, Atari ST, DOS, FM Towns, Mac OS, Mega-CD, Xbox 360, iPhone |

| Release | October 1990[1] |

| Genre(s) | Graphic adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The Secret of Monkey Island is an adventure game developed by Lucasfilm Games. The game spawned a number of sequels, collectively known as the Monkey Island series. Released in October 1990,[1] The Secret of Monkey Island is the fifth game to use the SCUMM engine. The game was primarily designed by Ron Gilbert, with Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman. The trio led the development of the sequel Monkey Island 2: LeChuck's Revenge.

Plot

The game begins on the Caribbean island of Mêlée, where a youth named Guybrush Threepwood wants to be a pirate. He seeks out the Pirate Leaders, who set him three challenges to prove himself a pirate: defeat Carla the island's swordmaster in insult swordfighting, steal a statue from the Governor's mansion, and find buried treasure.

Along the way he meets several interesting characters, including Stan the used boat salesman, Meathook (a fellow with hooks on both hands), a prisoner named Otis, the three men of low moral fiber and, most significantly, the gorgeous Governor Elaine Marley. The ghost pirate LeChuck, however, has been in love with Elaine since his living days. While Guybrush is busy, LeChuck's ghost crew abduct her, taking her to Monkey Island. Guybrush gathers a crew (Carla, Meathook, and Otis), buys a boat, and sets out to find the mysterious island and free Elaine.

When Guybrush finally reaches Monkey Island, he explores it and discovers a band of cannibals and a strange hermit named Herman Toothrot. After he helps the cannibals recover a lost voodoo ingredient (a magical root), they provide him with a seltzer bottle filled with "voodoo root elixir" that can destroy ghosts. However, when Guybrush goes after LeChuck, he is told that LeChuck went to Mêlée Island to marry Elaine.

Guybrush returns to Mêlée and goes to the church to prevent the wedding. When he arrives at the church wedding, he realises that Elaine had her own plan to escape. Guybrush loses the elixir and LeChuck starts beating him, until they arrive at the ship emporium where he finds a bottle of root beer. Substituting the lost ghost-fighting elixir for the root beer, he sprays LeChuck and the ghost pirate is destroyed. With LeChuck defeated, Guybrush and Elaine enjoy a romantic moment, watching fireworks.

Development

The Secret of Monkey Island was a project led by Ron Gilbert and designed by Gilbert with Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman. Gilbert originally intended to work on the title in 1988, after his work on Maniac Mansion, but the project was put on hold for the production of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure.[2][3]

The game was conceived from Gilbert's interest in pirates, and a desire to avoid traditional fantasy themes.[4][5] In interviews conducted at the time of the game's release, he stated that the Pirates of the Caribbean theme park ride at Disneyland inspired him to create an explorable world populated by swashbuckling pirates.[3] Later, he explained that while the ride informed the game's ambience, inspiration for the characters and voodoo themes came from Tim Powers' 1988 book On Stranger Tides.[4][5]

Gilbert developed his ideas through a series of short stories, which he shared with colleagues.[6] One of these stories introduced ghosts, a theme that would become central to the game. Once an initial story draft was written and the budget and schedule were approved, Schafer and Grossman began programming.[3] The pair, who also contributed about two thirds of the dialogue, took three months to put together a rough, working version of the game.[3] The team then used this early version, with place-holder art and no animation, to significantly tweak the game's content and pacing. Some sections of gameplay were removed altogether, and new characters and puzzles were added.[6]

Emphasis was put on making the game enjoyable and accessible to all players. The player character cannot die (except if the player encounters a certain easter egg) or trigger a game over and no puzzle ever becomes impossible to solve. Certain objectives are non-linear; for example, Guybrush must defeat a swordmaster, steal a statue, and find buried treasure at the beginning of the game. These three tasks may be accomplished in any order.[6]

Art for the game was created by Steve Purcell and Mark Ferrari.[3] The game's soundtrack was primarily composed by Michael Land in MIDI format. Another notable contributor was Orson Scott Card, acclaimed author of Ender's Game, who wrote the insults for the "insult swordfighting" section.[7]

As the release date approached, the game was behind schedule, and so members of the development team and other LucasFilm employees were asked to help assemble game boxes for the initial shipment.[8] In an interview at the time, Gilbert was quoted as saying, "I'm glad it's done. It's been two and a half years and a lot of hard work, but a lot of fun, too. We hope everyone has a great time playing it."[3]

Release

Original versions

The game was originally released on floppy disk in 1990 for Atari ST, Macintosh and PC systems (using EGA graphics);[9] it is also the first adventure game to use character scaling that showed Guybrush shrinking or enlarging according to his position on screen.[10]

The game box included a code wheel dubbed "Dial-A-Pirate" as a primitive form of copy protection. The wheel consisted of two concentric circles, which could be turned in order to make identikit pirate faces that matched those displayed on screen. The game would show an image of a pirate, and ask when the pirate was hanged on a particular island. The player then had to reproduce the face by rotating the wheel, and then enter the year shown in the hole corresponding to the island.

Months after release, the PC version was re-released with VGA graphics;[11] the Amiga version, released shortly after this,[12] used the PC EGA version's 16-color character graphics along with the PC VGA version's room backgrounds (reduced to 32 unique colors per room).

Enhanced editions

In June 1992, a CD-ROM version of the game was released, featuring improved music in the CD Digital Audio format. The release added graphical verb and inventory icons in the style of the 1991 sequel Monkey Island 2. The interface of the original version uses 12 verbs from which the player can select to perform actions, including ones that are rarely and optionally used in the game such as "Turn on" and "Turn off". In the CD version, the interface is changed to use ten verbs, with the default "Walk to" verb no longer appearing in the verb selection.

| Open | Walk to | Use |

| Close | Pick up | Look at |

| Push | Talk to | Turn on |

| Pull | Give | Turn off |

| Give | Pick up | Use |

| Open | Look at | Push |

| Close | Talk to | Pull |

The CD-ROM version was ported to the FM Towns system in the third quarter of 1992, and then in 1993 to the Sega CD. The Sega CD version used a password system to "save" the game, and did not save the various items the character had acquired, but always saved the items needed. It also suffered from long load times, due to the single-speed CD-ROM drive of the system, and was reduced from 256 to 64 colors, giving the Sega CD version a slightly washed-out look.

The lack of commercial success of the Sega CD version prompted LucasArts to cancel plans to release Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis and Monkey Island 2 on that system,[citation needed] and the Monkey Island series did not appear as a console release again until Escape from Monkey Island in 2000.

Special Edition

| The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition | |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | LucasArts |

| Publisher(s) | LucasArts |

| Series | Monkey Island |

| Platform(s) | Microsoft Windows Xbox 360 iPhone PlayStation 3 Mac OS X |

| Release | July 15, 2009 |

| Genre(s) | Graphic adventure |

The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition is an enhanced remake of The Secret of Monkey Island for the PC, Xbox Live Arcade and iPhone/iPod touch developed internally by LucasArts and released on 15 July 2009. The remake was announced on the first day of the 2009 Electronic Entertainment Expo along with the episodic Tales of Monkey Island.[13]

The Special Edition features new character art and hand-painted environments in the style of the original, presented in 1920 x 1080 widescreen resolution.[14][15] It also features a re-recorded and re-mastered score, and the principal voice artists from The Curse of Monkey Island read the previously unspoken lines, with Dominic Armato as Guybrush, Alexandra Boyd as Elaine, and Earl Boen as LeChuck.[16] The Xbox Live version, to meet specifications, uses compressed audio and artwork, but these assets remain uncompressed in the PC version.[17]

The interface itself is streamlined, hiding the verb table and inventory that previously took up the lower part of the screen. These, including the nine-option verb table from the enhanced editions of the game, can be pulled up as a menu, while verbs can also be selected by cycling through pre-set commands.[15] Another new feature is the three-level hint system, which (at the third level) presents a bright yellow arrow showing the player where to go.[15]

It is possible to switch between the 256 color enhanced and the new version of graphics without interrupting the flow of the game.[14] This also switches between the original CD Audio soundtrack and the remastered score with ambient sound effects, and the loss of voice-over work for the original version. The game did insert Spiffy, the famous dog on the back of the original game's box, and remove the infamous stump joke.[18]

LucasArts announced on March 10, 2010, that the Special Edition of Monkey Island 2: LeChuck's Revenge would be released for the PS3 via the PlayStation Network, Xbox 360 via Xbox Live Arcade, PC and Mac in Summer 2010.[19]

Reception

Critical reaction

| Title | Metacritic | GameRankings |

|---|---|---|

| "The Secret of Monkey Island" (1990) | ||

| "The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition" (2009) | ||

| "The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition" (X360) | ||

| "The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition" (iPhone) |

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2007) |

The game received a mainly positive reaction from the press. Amiga Power magazine described it as "the first truly accessible adventure" and awarded it 90% while Computer + Video Game described the PC version as "utterly enthralling" and awarded it 94%.[26][27]

At Metacritic the Special Edition scored 86/100.

The game was reviewed in 1991 in Dragon #168 by Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk Lesser in "The Role of Computers" column. The reviewers gave the game 5 out of 5 stars.[28]

The game is also in IGN's Video Game Hall of fame.

In-jokes

LucasArts

The game contains a few references to the LucasArts game Loom. The SCUMM Bar contains a character from Loom, Cobb, wearing a pirate hat and a button reading "Ask me about Loom". If Guybrush tries to hold a normal conversation with him, the only thing he says is "Aye". If asked about Loom, he launches into an enthusiastic sales pitch for the game, which, once initiated, cannot be skipped. The game also includes a seagull from Loom as well as several references, including the opening scene for the game. Having been launched out of a cannon, one of Guybrush's dialogue options is "I'm Bobbin, are you my mother?", a reference to Loom's protagonist Bobbin Threadbare.

- A similar joke is used again in The Curse of Monkey Island where Guybrush talks to a man sitting in a restaurant, who slumps on the table. It ends up being a skeleton who looks like Manny from Grim Fandango who is wearing a button saying "Ask me about Grim Fandango". When you talk to him, Guybrush tries to get some information about Grim Fandango, but as the skeleton is "dead," he does not reply. Guybrush comments that he is a poor pitchman, and will not talk to him anymore, instead simply replying: "I don't want to ask him about Grim Fandango."

The reference to Loom is retained in the remake despite the game not being published at the time, with Brooks Brown, Lucasarts' community manager, noting they had considered updating the reference to Star Wars: The Force Unleashed but realized the game would not be the same without the original joke.[29] However, just prior to the Special Edition release, LucasArts announced that Loom, along with other classic games from their back catalog, would be made available on Steam.

The game also pokes fun at the gaming conventions of game over. Though it is usually not possible to die in The Secret of Monkey Island, Guybrush can at a point in the game fall off a tall mountain. This prompts a dialog box proclaiming, "Oh, no! You've really screwed up this time! Guess you'll have to start over! Hope you saved the game!" and offering the choices "Restore, Restart, or Quit". This is similar to the death scenes of rival company Sierra Entertainment's adventure games of the time; seconds later, however, Guybrush bounces back into view and lands safely on the path. He offers the concise explanation, "Rubber tree", and the game continues as normal.

However, it is actually possible to die in the first chapter. At one point Guybrush becomes trapped underwater. He is famously able to hold his breath for ten minutes, but after that time he drowns. In The Curse of Monkey Island, if the player keeps telling Guybrush to go into the ocean, he eventually agrees to do so. This takes him to this particular death scene to which he comments with something like "Guess he couldn't hold his breath." And walks off. The gag uses the same VGA graphics of the first game, while the Curse Guybrush remains normal. Both games ran on the SCUMM engine.

Stump joke

One infamous joke, which many players assumed was a technical error, involved a stump in a forest.[30] When examining the stump, Guybrush proclaims that a hole in it leads to a maze of caverns. If Guybrush tries to climb down into the stump, the game prompts the player to successively insert "disk #23," "disk #47", and "disk #114", though the game was distributed on four or eight floppy disks. After the "Disk 114" prompt, Guybrush states, "Oh well. I guess I'll just have to skip that part of the game."

The endgame credits also have an entry for "art and animation for disk #23." Many people did not get the joke, and LucasArts tech support received quite a large number of calls for help with the missing disk.[citation needed] The joke was removed for the Sega CD, PC CD and 2009 Special Edition versions of the game. It was, however, mentioned in the sequel: Guybrush can call the LucasArts hint line from a phone and ask, "Who thought up that dumb stump joke?", to which the annoyed operator answers, "I'm tired of hearing about that damn stump. Do you have any idea how many calls I get a DAY about that?"

In Curse, Guybrush briefly sticks his head into an opening found at the backside wall in the Goodsoup family crypt, which leads to the very same tree stump rendered in VGA-style graphics, including the original GUI (the SCUMM Engine), and the original music from the Melee Island forest, while Guybrush is displayed in the cartoon style of Curse.[31] He is then quickly forced to escape back through the hole as he spots a horde of "stunningly rendered rabid jaguars" off-screen.

The stump joke is also revisited in the game Grim Fandango where Manny Calavera will repeat the line of "Wow! It's a tunnel that opens onto a system of catacombs!", which is what Guybrush says when he examines the stump. In Tim Schafer's Psychonauts examining a hollow stump causes a similar reply, only this time it does lead to a system of catacombs, serving as a travel system for the game.[32]

Grog In The News

The Grog recipe found in Monkey Island was mistakenly reported as real by the Argentinian news channel C5N, which urged teenagers not to drink the dangerous drink.[33]

References

- ^ a b http://web.archive.org/web/20060623025112/http://www.lucasarts.com/20th/history_2.htm

- ^ Demaria, Rusel; Wilson, Johnny L. (2003), High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games, McGraw-Hill Professional, pp. 200–201, ISBN 9780072231724

- ^ a b c d e f "The Secret of Creating Monkey Island — An Interview With Ron Gilbert". LucasFilm Adventurer vol. 1, number 1 (online transcript). 1990. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- ^ a b What's eating Gilbert?, Computer and Video Games, 7 September 2005, retrieved 14 June 2009

- ^ a b Ron Gilbert (20 September 2004). "On Stranger Tides". GrumpyGamer. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- ^ a b c Interview with Ron Gilbert, Edge (magazine)

- ^ Gaudiosi, John (10 November 2006). "Orson Scott Card Builds an Empire". Wired.com. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ^ Interview with Ron Gilbert, Edge (magazine)

- ^ A UK magazine reviewed the then recently released PC EGA version in its November 1990 issue (Houghton, Gordon (November 1990), "The Secret of Monkey Island", The One, no. 26, pp. 130–132).

- ^ "Lucasfilm games' new graphic adventure delivers swashbuckling mystery and salty humor" (Press release). Lucasfilm Games. 2 June 1990. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- ^ A UK magazine reviewed the new, PC VGA version in July 1991 ("The Secret of Monkey Island", ACE, no. 46, pp. 76–77, July 1991).

- ^ The Amiga and ST versions were released (in the UK) in January of 1991 ("ACE diary", ACE, no. 41, p. 117, February 1991).

- ^ O'Conner, Alice (1 June 2009). "Monkey Island Series to Continue, Secret of Monkey Island to Be Revamped". Shacknews. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ a b Monkey Island Special Edition officially announced, Adventure Gamers, 1 June 2009, retrieved 3 June 2009

- ^ a b c The Secret of Monkey Island Special Edition First Look, Gamespot, 1 June 2009, retrieved 3 June 2009

- ^ PREVIEW: The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition, Adventure Gamers, 6 June 2009, retrieved 10 June 2009

- ^ Klepek, Patrick (16 July 2009). "Why The Secret of Monkey Island Is Over 2GB On PC, But Not Xbox 360". G4 TV. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ Hatfield, Daemon (14 July 2009). "The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition Review". IGN. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ Crecente, Brian (2010-03-10). "Monkey Island 2 Special Edition Hits this Summer". Kotaku. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ "The Secret of Monkey Island (PC: 1990) Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition (PC: 2009) Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition (PC:2009) Reviews". GameRankings. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition (X360:2009) Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition (X360:2009) Reviews". GameRankings. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition (iPhone:2009) Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ Ramshaw, Mark (June 1991). "Game Reviews: The Secret of Monkey Island". Amiga Power Issue 2. Future Publishing. pp. 22–24.

- ^ Glancey, Paul (December 1990). "The Secret of Monkey Island Review". Computer and Video Games Magazine Issue 109. EMAP. pp. 112–114.

- ^

Lesser, Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk (April 1991). "The Role of Computers". Dragon (168): 47–54.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hill, Jason (18 June 2009). "By George, it's Monkey magic". WAtoday. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "Psychonauts — Covered by Razputin's Domain". V2.razputin.net. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ^ "Argentine TV Warns World of Monkey Island's Grog Recipe — fail". Kotaku. 2009-08-30. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

External links

- The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition Official Website

- The Secret of Monkey Island at MobyGames

- The Secret of Monkey Island on the Monkey Island wiki

- The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition on the Monkey Island wiki

- The Monkey Island Speech Project

- Soundtrack (CD audio version)

- Soundtrack (MT-32 version)