Kharoṣṭhī

|name=Kharoṣṭhī

|type=Abugida

|languages=Gandhari

Prakrit

Tocharian

Kuchean

|fam1=Aramaic alphabet

|fam2=Proto-Canaanite alphabet

|fam3=Phoenician alphabet

|fam4=Aramaic alphabet

|sisters=Brāhmī

Nabataean

Syriac

Palmyrenean

Mandaic

Pahlavi

Sogdian

|time=4th century BCE - 3rd century CE

|iso15924=Khar

|unicode=U+10A00—U+10A5F

}}

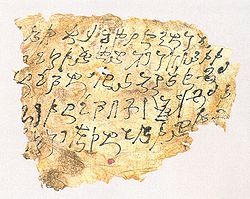

The Kharoṣṭhī script, is an ancient abugida (or "alphasyllabary") used by the Gandhara culture, nestled in the historic northwest South Asia to write the Gāndhārī and Sanskrit languages. It was in use from the middle of the 3rd century BCE until it died out in its homeland around the 3rd century CE. It was also in use in Kushan, Sogdiana (see Issyk kurgan) and along the Silk Road where there is some evidence it may have survived until the 7th century in the remote way stations of Khotan and Niya. Kharoṣṭhī is encoded in the Unicode range U+10A00—U+10A5F, from version 4.1.0.

Form

Kharoṣṭhī is mostly written right to left (type A), but some inscriptions (type B) already show the left to right direction that was to become universal for the later South Asian scripts.

Each syllable includes the short a sound by default, with other vowels being indicated by diacritic marks. Recent epigraphical evidence highlighted by Professor Richard Salomon of the University of Washington has shown that the order of letters in the Kharoṣṭhī script follows what has become known as the Arapacana Alphabet. As preserved in Sanskrit documents the alphabet runs:

- a ra pa ca na la da ba ḍa ṣa va ta ya ṣṭa ka sa ma ga stha ja śva dha śa kha kṣa sta jñā rtha (or ha) bha cha sma hva tsa gha ṭha ṇa pha ska ysa śca ṭa ḍha

Some variations in both the number and order of syllables occur in extant texts.

Kharoṣṭhī includes only one standalone vowel sign which is used for initial vowels in words. Other initial vowels use the a character modified by diacritics. Using epigraphic evidence Salomon has established that the vowel order is a e i o u, rather than the usual vowel order for Indic scripts a i u e o. This is the same as the Semitic vowel order. Also, there is no differentiation between long and short vowels in kharoshti. Both are marked using the same vowel markers

The alphabet was used by Buddhists as a mnemonic for remembering a series of verses relating to the nature of phenomena. In Tantric Buddhism this list was incorporated into ritual practices, and later became enshrined in mantras.

Alphabet

Numerals

| I | II | III | X | IX | IIX | IIIX | XX | IXX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| ੭ | Ȝ | ੭Ȝ | ȜȜ | ੭ȜȜ | ȜȜȜ | ੭ȜȜȜ | ||

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | ||

| ʎI | ʎII | |||||||

| 100 | 200 | |||||||

Kharoṣṭhī included a set of numerals that are reminiscent of Roman numerals. The symbols were I for the unit, X for four (perhaps representative of four lines or directions), ੭ for ten (doubled for twenty), and ʎ for the hundreds multiplier. The system is based on an additive and a multiplicative principle, but does not have the substractive feature used in the Roman number system.[1]

Note that the table beside reads right-to-left, just like the Kharoṣṭhī abugida itself and the displayed numbers.

The numerals are encoded by Unicode at codepoints U+10A40 to U+10A47:

| 10A40 𐩀 One

|

10A41 𐩁 Two

|

10A42 𐩂 Three

|

10A43 𐩃 Four

|

10A44 𐩄 Ten

|

10A45 𐩅 Twenty

|

10A46 𐩆 One Hundred

|

10A47 𐩇 One Thousand

|

History

The Kharoṣṭhī script was deciphered by James Prinsep (1799–1840), using the bilingual coins of the Indo-Greeks (Obverse in Greek, reverse in Pāli, using the Kharoṣṭhī script). This in turn led to the reading of the Edicts of Ashoka, some of which, from the northwest of the Asian subcontinent, were written in the Kharoṣṭhī script.

Scholars are not in agreement as to whether the Kharoṣṭhī script evolved gradually, or was the deliberate work of a single inventor. An analysis of the script forms shows a clear dependency on the Aramaic alphabet but with extensive modifications to support the sounds found in Indic languages. One model is that the Aramaic script arrived with the Achaemenid conquest of the region of northwest India in 500 BCE and evolved over the next 200+ years to reach its final form by the 3rd century BCE where it appears in some of the Edicts of Ashoka found in northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, notably Pakistan and Afghanistan. However, no intermediate forms have yet been found to confirm this evolutionary model, and rock and coin inscriptions from the 3rd century BCE onward show a unified and standard form.

The study of the Kharoṣṭhī script was recently invigorated by the discovery of the Gandharan Buddhist Texts, a set of birch-bark manuscripts written in Kharoṣṭhī, discovered near the Afghani city of Hadda just west of the Khyber Pass in Pakistan. The manuscripts were donated to the British Library in 1994. The entire set of manuscripts are dated to the 1st century CE, making them the oldest Buddhist manuscripts yet discovered.

-

A silver tetradrachm of the Indo-Greek king Philoxenus (100-95 BCE), with front legend in Greek and reverse legend in the Kharoṣṭhī script.

-

Coin of Gurgamoya, king of Khotan. Khotan, 1st century CE.

Tocharian languages

In the early 20th century inscriptions and documents in two new related (but mutually unintelligible) languages were discovered at various sites in the Tarim Basin written in Karosthi script. It was soon found that they belonged to the Indo-European family of languages. Our only records of the now-extinct "Tokharian A" (from the region of Turfan and Karashahr), and "Tokharian B" (mainly from the region of Kucha, but also found elsewhere), are of relatively late date – 6th to 8th century CE, when written records appear; but it is likely they arrived in the region much earlier. They are now extinct, and scholars are still trying to piece together a fuller picture of these languages, their origins, history and connections, etc.[2]

Kharosthi alphabet in Unicode

| 10A00 𐨀 A

|

10A01 𐨁 Vowel Sign I

|

10A02 𐨂 Vowel Sign U

|

10A03 𐨃 Vowel Sign Vocalic R

|

10A05 𐨅 Vowel Sign E

|

10A06 𐨆 Vowel Sign O

|

10A0C 𐨌 Vowel Length Mark

|

10A0D 𐨍 Sign Double Ring Below

|

10A0E 𐨎 Sign Anusvara

|

10A0F 𐨏 Sign Visarga

| ||||||

| 10A10 𐨐 Ka

|

10A11 𐨑 Kha

|

10A12 𐨒 Ga

|

10A13 𐨓 Gha

|

10A15 𐨕 Ca

|

10A16 𐨖 Cha

|

10A17 𐨗 Ja

|

10A19 𐨙 Nya

|

10A1A 𐨚 Tta

|

10A1B 𐨛 Ttha

|

10A1C 𐨜 Dda

|

10A1D 𐨝 Ddha

|

10A1E 𐨞 Nna

|

10A1F 𐨟 Ta

| ||

| 10A20 𐨠 Tha

|

10A21 𐨡 Da

|

10A22 𐨢 Dha

|

10A23 𐨣 Na

|

10A24 𐨤 Pa

|

10A25 𐨥 Pha

|

10A26 𐨦 Ba

|

10A27 𐨧 Bha

|

10A28 𐨨 Ma

|

10A29 𐨩 Ya

|

10A2A 𐨪 Ra

|

10A2B 𐨫 La

|

10A2C 𐨬 Va

|

10A2D 𐨭 Sha

|

10A2E 𐨮 Ssa

|

10A2F 𐨯 Sa

|

| 10A30 𐨰 Za

|

10A31 𐨱 Ha

|

10A32 𐨲 Kka

|

10A33 𐨳 Tttha

|

10A38 𐨸 Sign Bar Above

|

10A39 𐨹 Sign Cauda

|

10A3A 𐨺 Sign Dot Below

|

10A3F 𐨿 Virama

| ||||||||

| 10A40 𐩀 One

|

10A41 𐩁 Two

|

10A42 𐩂 Three

|

10A43 𐩃 Four

|

10A44 𐩄 Ten

|

10A45 𐩅 Twenty

|

10A46 𐩆 One Hundred

|

10A47 𐩇 One Thousand

|

||||||||

| 10A50 𐩐 Dot

|

10A51 𐩑 Small Circle

|

10A52 𐩒 Circle

|

10A53 𐩓 Crescent Bar

|

10A54 𐩔 Mangalam

|

10A55 𐩕 Lotus

|

10A56 𐩖 Danda

|

10A57 𐩗 Double Danda

|

10A58 𐩘 Lines

|

|||||||

See also

References

- ^ Graham Flegg, Numbers: Their History and Meaning, Courier Dover Publications, 2002, ISBN 9780486421650, p. 67f.

- ^ The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, pp. 270-296, 333-334. (2000). J. P. Mallory and Victor H. Mair. Thames & Hudson, London. ISBN 0-500-05101-1.

- Dani, Ahmad Hassan. Kharoshthi Primer, Lahore Museum Publication Series - 16, Lahore, 1979

- Falk, Harry. Schrift im alten Indien: Ein Forschungsbericht mit Anmerkungen, Gunter Narr Verlag, 1993 (in German)

- Fussman's, Gérard. Les premiers systèmes d'écriture en Inde, in Annuaire du Collège de France 1988-1989 (in French)

- Hinüber, Oscar von. Der Beginn der Schrift und frühe Schriftlichkeit in Indien, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1990 (in German)

- Nasim Khan, M. Kharoshthi Manuscripts from Gandhara (2nd ed.): 2009. First published in 2008.

- Norman, Kenneth R. The Development of Writing in India and its Effect upon the Pâli Canon, in Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens (36), 1993

- Salomon, Richard. New evidence for a Ganghari origin of the arapacana syllabary. Journal of the American Oriental Society. Apr-Jun 1990, Vol.110 (2), p.255-273.

- Salomon, Richard. An additional note on arapacana. Journal of the American Oriental Society. 1993, Vol.113 (2), p.275-6.

- Salomon, Richard. Kharoṣṭhī syllables used as location markers in Gāndhāran stūpa architecture. Pierfrancesco Callieri, ed., Architetti, Capomastri, Artigiani: L’organizzazione dei cantieri e della produzione artistica nell’asia ellenistica. Studi offerti a Domenico Faccenna nel suo ottantesimo compleanno. (Serie Orientale Rome 100; Rome: Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente, 2006), pp. 181-224.

External links

- List of all known Kharoṣṭhī (Gandhārī) inscriptions.

- information on the Kharoṣṭhī alphabet by Omniglot

- A Preliminary Study of Kharoṣṭhī Manuscript Paleography by Andrew Glass, University of Washington (2000)

- On The Origin Of The Early Indian Scripts: A Review Article by Richard Salomon, University of Washington (via archive.org)

- Proposal to encode Kharoṣṭhī in Unicode (includes good background info)