Fuel cell

A fuel cell is an electrochemical cell that converts chemical energy from a fuel into electric energy. Electricity is generated from the reaction between a fuel supply and an oxidizing agent. The reactants flow into the cell, and the reaction products flow out of it, while the electrolyte remains within it. Fuel cells can operate continuously as long as the necessary reactant and oxidant flows are maintained.

Fuel cells are different from conventional electrochemical cell batteries in that they consume reactant from an external source, which must be replenished[1] – a thermodynamically open system. By contrast, batteries store electric energy chemically and hence represent a thermodynamically closed system.

Many combinations of fuels and oxidants are possible. A hydrogen fuel cell uses hydrogen as its fuel and oxygen (usually from air) as its oxidant. Other fuels include hydrocarbons and alcohols. Other oxidants include chlorine and chlorine dioxide.[2]

Fuel cells were invented by the German inventor Christian Friedrich Schönbein.

Design

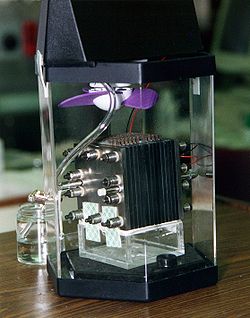

Fuel cells come in many varieties; however, they all work in the same general manner. They are made up of three segments which are sandwiched together: the anode, the electrolyte, and the cathode. Two chemical reactions occur at the interfaces of the three different segments. The net result of the two reactions is that fuel is consumed, water or carbon dioxide is created, and an electric current is created, which can be used to power electrical devices, normally referred to as the load.

At the anode a catalyst oxidizes the fuel, usually hydrogen, turning the fuel into a positively charged ion and a negatively charged electron. The electrolyte is a substance specifically designed so ions can pass through it, but the electrons cannot. The freed electrons travel through a wire creating the electric current. The ions travel through the electrolyte to the cathode. Once reaching the cathode, the ions are reunited with the electrons and the two react with a third chemical, usually oxygen, to create water or carbon dioxide.

The most important design features in a fuel cell are:

- The electrolyte substance. The electrolyte substance usually defines the type of fuel cell.

- The fuel that is used. The most common fuel is hydrogen.

- The anode catalyst, which breaks down the fuel into electrons and ions. The anode catalyst is usually made up of very fine platinum powder.

- The cathode catalyst, which turns the ions into the waste chemicals like water or carbon dioxide. The cathode catalyst is often made up of nickel.

A typical fuel cell produces a voltage from 0.6 V to 0.7 V at full rated load. Voltage decreases as current increases, due to several factors:

- Activation loss

- Ohmic loss (voltage drop due to resistance of the cell components and interconnects)

- Mass transport loss (depletion of reactants at catalyst sites under high loads, causing rapid loss of voltage).[3]

To deliver the desired amount of energy, the fuel cells can be combined in series and parallel circuits, where series yields higher voltage, and parallel allows a higher current to be supplied. Such a design is called a fuel cell stack. The cell surface area can be increased, to allow stronger current from each cell.

Proton exchange membrane fuel cells

In the archetypical hydrogen–oxygen proton exchange membrane fuel cell[4] (PEMFC) design, a proton-conducting polymer membrane, (the electrolyte), separates the anode and cathode sides. This was called a "solid polymer electrolyte fuel cell" (SPEFC) in the early 1970s, before the proton exchange mechanism was well-understood. (Notice that "polymer electrolyte membrane" and "proton exchange mechanism" result in the same acronym.)

On the anode side, hydrogen diffuses to the anode catalyst where it later dissociates into protons and electrons. These protons often react with oxidants causing them to become what is commonly referred to as multi-facilitated proton membranes. The protons are conducted through the membrane to the cathode, but the electrons are forced to travel in an external circuit (supplying power) because the membrane is electrically insulating. On the cathode catalyst, oxygen molecules react with the electrons (which have traveled through the external circuit) and protons to form water — in this example, the only waste product, either liquid or vapor.

In addition to this pure hydrogen type, there are hydrocarbon fuels for fuel cells, including diesel, methanol (see: direct-methanol fuel cells and indirect methanol fuel cells) and chemical hydrides. The waste products with these types of fuel are carbon dioxide and water.

The different components of a PEMFC are (i) bipolar plates, (ii) electrodes, (iii) catalyst, (iv) membrane, and (v) the necessary hardwares.[7] The materials used for different parts of the fuel cells differ by type. The bipolar plates may be made of different types of materials, such as, metal, coated metal, graphite, flexible graphite, C–C composite, carbon–polymer composites etc.[8] The membrane electrode assembly (MEA), is referred as the heart of the PEMFC and usually made of a proton exchange membrane sandwiched between two catalyst coated carbon papers. Platinum and/or similar type of noble metals are usually used as the catalyst for PEMFC. The electrolyte could be a polymer membrane.

Proton exchange membrane fuel cell design issues

- Costs. In 2002, typical fuel cell systems cost US$100 per kilowatt of electric power output.[9] In 2009, the Department of Energy reported that 80-kW automotive fuel cell system costs in volume production (projected to 500,000 units per year) are $61 per kilowatt.[10] The goal is $35 per kilowatt. Cost reduction will help PEM fuel cells compete with current market technologies including gasoline internal combustion engines. Many companies are working on techniques to reduce cost in a variety of ways including reducing the amount of platinum needed in each individual cell. Ballard Power Systems has experiments with a catalyst enhanced with carbon silk which allows a 30% reduction (1 mg/cm² to 0.7 mg/cm²) in platinum usage without reduction in performance.[11] Monash University, Melbourne uses PEDOT as a cathode.[12] A 2011 published study[13] documented the first ever metal free electrocatalyst using relatively inexpensive doped carbon nanotubes that are less than 1% the cost of platinum and are of equal or superior performance.

- In 2005 Ballard Power Systems announced that its fuel cells will use Solupor, a porous polyethylene film patented by DSM.[14][15]

- Water and air management[16] (in PEMFCs). In this type of fuel cell, the membrane must be hydrated, requiring water to be evaporated at precisely the same rate that it is produced. If water is evaporated too quickly, the membrane dries, resistance across it increases, and eventually it will crack, creating a gas "short circuit" where hydrogen and oxygen combine directly, generating heat that will damage the fuel cell. If the water is evaporated too slowly, the electrodes will flood, preventing the reactants from reaching the catalyst and stopping the reaction. Methods to manage water in cells are being developed like electroosmotic pumps focusing on flow control. Just as in a combustion engine, a steady ratio between the reactant and oxygen is necessary to keep the fuel cell operating efficiently.

- Temperature management. The same temperature must be maintained throughout the cell in order to prevent destruction of the cell through thermal loading. This is particularly challenging as the 2H2 + O2 -> 2H2O reaction is highly exothermic, so a large quantity of heat is generated within the fuel cell.

- Durability, service life, and special requirements for some type of cells. Stationary fuel cell applications typically require more than 40,000 hours of reliable operation at a temperature of -35 °C to 40 °C (-31 °F to 104 °F), while automotive fuel cells require a 5,000 hour lifespan (the equivalent of 150,000 miles) under extreme temperatures. Current service life is 7,300 hours under cycling conditions.[17] Automotive engines must also be able to start reliably at -30 °C (-22 °F) and have a high power to volume ratio (typically 2.5 kW per liter).

- Limited carbon monoxide tolerance of some (non-PEDOT) cathodes.

High temperature fuel cells

SOFC

A solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) is extremely advantageous “because of a possibility of using a wide variety of fuel”.[18] Unlike most other fuel cells which only use hydrogen, SOFCs can run on hydrogen, butane, methanol, other petroleum products and producer gases from biomass gasification [19]. The different fuels each have their own chemistry.

For SOFC methanol fuel cells, on the anode side, a catalyst breaks methanol and water down to form carbon dioxide, hydrogen ions, and free electrons. The hydrogen ions meet oxide ions that have been created on the cathode side and passed across the electrolyte to the anode side, where they react to create water. A load connected externally between the anode and cathode completes the electrical circuit. Below are the chemical equations for the reaction:

Anode Reaction: CH3OH + H2O + 3O= → CO2 + 3H2O + 6e-

Cathode Reaction: 3/2 O2 + 6e- → 3O=

Overall Reaction: CH3OH + 3/2 O2 → CO2 + 2H2O + electrical energy

At the anode SOFCs can use nickel or other catalysts to break apart the methanol and create hydrogen ions and carbon monoxide. A solid called yttria stabilized zirconia (YSZ) is used as the electrolyte. Like all fuel cell electrolytes YSZ is conductive to certain ions, in this case the oxide ion (O=) allowing passage from the cathode to anode, but is non-conductive to electrons. It is a durable solid, advantageous in large industrial systems, and a good ion conductor. However, YSZ only works at very high temperatures, typically about 950oC.[20] High operating temperature presents both advantages and disadvantages. Running the fuel cell at such a high temperature easily breaks down the methane and oxygen into ions. It also removes the need for precious-metal catalyst, thereby reducing cost. Additionally, waste heat from SOFC systems may be captured and reused, which increases overall efficiency to 80%-85%.[21] One disadvantage of the high operating temperature is slow start up time. This makes transportation applications not ideal for SOFCs. Another disadvantage is the potential for other unwanted reactions to occur inside the fuel cell. It is common for carbon dust (graphite) to build up on the anode, preventing the fuel from reaching the catalyst. However, current research is focused on this "carbon coking" problem. Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have shown that the use of copper (Cu)-based cermets dramatically reduces coking and loss of performance during service due to coking.[22] There is also research being done to find alternatives to YSZ that will carry ions at a lower temperature as well as finding ways to reduce operating temperature while still using YSZ as the electrolyte.[23]

MCFC

Molten carbonate fuel cells (MCFCs) operate in a similar manner, except the electrolyte consists of liquid (molten) carbonate, which is a negative ion and an oxidizing agent. Because the electrolyte loses carbonate in the oxidation reaction, the carbonate must be replenished through some means. This is often performed by recirculating the carbon dioxide from the oxidation products into the cathode where it reacts with the incoming air and reforms carbonate.

Unlike proton exchange fuel cells, the catalysts in SOFCs and MCFCs are not poisoned by carbon monoxide, due to much higher operating temperatures. Because the oxidation reaction occurs in the anode, direct utilization of the carbon monoxide is possible. Also, steam produced by the oxidation reaction can shift carbon monoxide and steam reform hydrocarbon fuels inside the anode. These reactions can use the same catalysts used for the electrochemical reaction, eliminating the need for an external fuel reformer.

MCFC can be used for reducing the CO2 emission from coal fired power plants[24] as well as gas turbine power plants.[25]

History

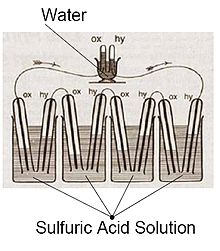

The principle of the fuel cell was discovered by German scientist Christian Friedrich Schönbein in 1838 and published in one of the scientific magazines of the time.[26] Based on this work, the first fuel cell was demonstrated by Welsh scientist and barrister Sir William Robert Grove in the February 1839 edition of the Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science[27] and later sketched, in 1842, in the same journal.[28] The fuel cell he made used similar materials to today's phosphoric-acid fuel cell.

In 1955, W. Thomas Grubb, a chemist working for the General Electric Company (GE), further modified the original fuel cell design by using a sulphonated polystyrene ion-exchange membrane as the electrolyte. Three years later another GE chemist, Leonard Niedrach, devised a way of depositing platinum onto the membrane, which served as catalyst for the necessary hydrogen oxidation and oxygen reduction reactions. This became known as the 'Grubb-Niedrach fuel cell'. GE went on to develop this technology with NASA and McDonnell Aircraft, leading to its use during Project Gemini. This was the first commercial use of a fuel cell. It wasn't until 1959 that British engineer Francis Thomas Bacon successfully developed a 5 kW stationary fuel cell. In 1959, a team led by Harry Ihrig built a 15 kW fuel cell tractor for Allis-Chalmers which was demonstrated across the US at state fairs. This system used potassium hydroxide as the electrolyte and compressed hydrogen and oxygen as the reactants. Later in 1959, Bacon and his colleagues demonstrated a practical five-kilowatt unit capable of powering a welding machine. In the 1960s, Pratt and Whitney licensed Bacon's U.S. patents for use in the U.S. space program to supply electricity and drinking water (hydrogen and oxygen being readily available from the spacecraft tanks). In 1991, the first hydrogen fuel cell automobile was developed by Roger Billings.[29]

United Technologies Corporation's UTC Power subsidiary was the first company to manufacture and commercialize a large, stationary fuel cell system for use as a co-generation power plant in hospitals, universities and large office buildings. UTC Power continues to market this fuel cell as the PureCell 200, a 200 kW system (although soon to be replaced by a 400 kW version, expected for sale in late 2009[needs update]).[30] UTC Power continues to be the sole supplier of fuel cells to NASA for use in space vehicles, having supplied the Apollo missions,[31] and currently the Space Shuttle program, and is developing fuel cells for automobiles, buses, and cell phone towers; the company has demonstrated the first fuel cell capable of starting under freezing conditions with its proton exchange membrane.

Types of fuel cell

| Fuel cell name | Electrolyte | Qualified power (W) | Working temperature (°C) | Efficiency (cell) | Efficiency (system) | Status | Cost (USD/W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal hydride fuel cell | Aqueous alkaline solution | > -20 (50% Ppeak @ 0°C) |

Commercial / Research | ||||

| Electro-galvanic fuel cell | Aqueous alkaline solution | < 40 | Commercial / Research | ||||

| Direct formic acid fuel cell (DFAFC) | Polymer membrane (ionomer) | < 50 W | < 40 | Commercial / Research | |||

| Zinc-air battery | Aqueous alkaline solution | < 40 | Mass production | ||||

| Microbial fuel cell | Polymer membrane or humic acid | < 40 | Research | ||||

| Upflow microbial fuel cell (UMFC) | < 40 | Research | |||||

| Regenerative fuel cell | Polymer membrane (ionomer) | < 50 | Commercial / Research | ||||

| Direct borohydride fuel cell | Aqueous alkaline solution | 70 | Commercial | ||||

| Alkaline fuel cell | Aqueous alkaline solution | 10 – 100 kW | < 80 | 60–70% | 62% | Commercial / Research | |

| Direct methanol fuel cell | Polymer membrane (ionomer) | 100 mW – 1 kW | 90–120 | 20–30% | 10–20% | Commercial / Research | 125 |

| Reformed methanol fuel cell | Polymer membrane (ionomer) | 5 W – 100 kW | 250–300 (Reformer) 125–200 (PBI) |

50–60% | 25–40% | Commercial / Research | |

| Direct-ethanol fuel cell | Polymer membrane (ionomer) | < 140 mW/cm² | > 25 ? 90–120 |

Research | |||

| Proton exchange membrane fuel cell | Polymer membrane (ionomer) | 100 W – 500 kW | 50–120 (Nafion) 125–220 (PBI) |

50–70% | 30–50% | Commercial / Research | 30–35 |

| RFC - Redox | Liquid electrolytes with redox shuttle and polymer membrane (Ionomer) | 1 kW – 10 MW | Research | ||||

| Phosphoric acid fuel cell | Molten phosphoric acid (H3PO4) | < 10 MW | 150-200 | 55% | 40% Co-Gen: 90% |

Commercial / Research | 4–4.50 |

| Molten carbonate fuel cell | Molten alkaline carbonate | 100 MW | 600-650 | 55% | 47% | Commercial / Research | |

| Tubular solid oxide fuel cell (TSOFC) | O2--conducting ceramic oxide | < 100 MW | 850-1100 | 60–65% | 55–60% | Commercial / Research | |

| Protonic ceramic fuel cell | H+-conducting ceramic oxide | 700 | Research | ||||

| Direct carbon fuel cell | Several different | 700-850 | 80% | 70% | Commercial / Research | ||

| Planar Solid oxide fuel cell | O2--conducting ceramic oxide | < 100 MW | 500-1100 | 60–65% | 55–60% | Commercial / Research | |

| Enzymatic Biofuel Cells | Any that will not denature the enzyme | < 40 | Research | ||||

| Magnesium-Air Fuel Cell | salt water | -20 - 55 | 90% | Commercial / Research |

Efficiency

Fuel cell efficiency

The efficiency of a fuel cell is dependent on the amount of power drawn from it. Drawing more power means drawing more current, which increases the losses in the fuel cell. As a general rule, the more power (current) drawn, the lower the efficiency. Most losses manifest themselves as a voltage drop in the cell, so the efficiency of a cell is almost proportional to its voltage. For this reason, it is common to show graphs of voltage versus current (so-called polarization curves) for fuel cells. A typical cell running at 0.7 V has an efficiency of about 50%, meaning that 50% of the energy content of the hydrogen is converted into electrical energy; the remaining 50% will be converted into heat. (Depending on the fuel cell system design, some fuel might leave the system unreacted, constituting an additional loss.)

For a hydrogen cell operating at standard conditions with no reactant leaks, the efficiency is equal to the cell voltage divided by 1.48 V, based on the enthalpy, or heating value, of the reaction. For the same cell, the second law efficiency is equal to cell voltage divided by 1.23 V. (This voltage varies with fuel used, and quality and temperature of the cell.) The difference between these numbers represents the difference between the reaction's enthalpy and Gibbs free energy. This difference always appears as heat, along with any losses in electrical conversion efficiency.

Fuel cells are not heat engines and so the Carnot cycle efficiency is not relevant to the thermodynamic efficiency of fuel cells.[32] At times this is misrepresented by saying that fuel cells are exempt from the laws of thermodynamics, because most people think of thermodynamics in terms of combustion processes (enthalpy of formation). The laws of thermodynamics also hold for chemical processes (Gibbs free energy) like fuel cells, but the maximum theoretical efficiency is higher (83% efficient at 298K [33] in the case of hydrogen/oxygen reaction) than the Otto cycle thermal efficiency (60% for compression ratio of 10 and specific heat ratio of 1.4). Comparing limits imposed by thermodynamics is not a good predictor of practically achievable efficiencies. Also, if propulsion is the goal, electrical output of the fuel cell has to still be converted into mechanical power with another efficiency drop. In reference to the exemption claim, the correct claim is that "limitations imposed by the second law of thermodynamics on the operation of fuel cells are much less severe than the limitations imposed on conventional energy conversion systems".[34] Consequently, they can have very high efficiencies in converting chemical energy to electrical energy, especially when they are operated at low power density, and using pure hydrogen and oxygen as reactants.

It should be underlined that fuel cell (especially high temperature) can be used as a heat source in conventional heat engine (gas turbine system). In this case the ultra high efficiency is predicted (above 70%).[35][36]

In practice

For a fuel cell operating on air, losses due to the air supply system must also be taken into account. This refers to the pressurization of the air and dehumidifying it. This reduces the efficiency significantly and brings it near to that of a compression ignition engine. Furthermore, fuel cell efficiency decreases as load increases.

The tank-to-wheel efficiency of a fuel cell vehicle is greater than 45% at low loads [37] and shows average values of about 36% when a driving cycle like the NEDC (New European Driving Cycle) is used as test procedure.[38] The comparable NEDC value for a Diesel vehicle is 22%. In 2008 Honda released a fuel cell electric vehicle (the Honda FCX Clarity) with fuel stack claiming a 60% tank-to-wheel efficiency.[39]

It is also important to take losses due to fuel production, transportation, and storage into account. Fuel cell vehicles running on compressed hydrogen may have a power-plant-to-wheel efficiency of 22% if the hydrogen is stored as high-pressure gas, and 17% if it is stored as liquid hydrogen.[40] In addition to the production losses, over 70% of US' electricity used for hydrogen production comes from thermal power, which only has an efficiency of 33% to 48%, resulting in a net increase in carbon dioxide production by using hydrogen in vehicles[citation needed]. However, more than 90% of all hydrogen is produced by steam methane reforming.[41]

Fuel cells cannot store energy like a battery, but in some applications, such as stand-alone power plants based on discontinuous sources such as solar or wind power, they are combined with electrolyzers and storage systems to form an energy storage system. The overall efficiency (electricity to hydrogen and back to electricity) of such plants (known as round-trip efficiency) is between 30 and 50%, depending on conditions.[42] While a much cheaper lead-acid battery might return about 90%, the electrolyzer/fuel cell system can store indefinite quantities of hydrogen, and is therefore better suited for long-term storage.

Solid-oxide fuel cells produce exothermic heat from the recombination of the oxygen and hydrogen. The ceramic can run as hot as 800 degrees Celsius. This heat can be captured and used to heat water in a micro combined heat and power (m-CHP) application. When the heat is captured, total efficiency can reach 80-90% at the unit, but does not consider production and distribution losses. CHP units are being developed today for the European home market.

Fuel cell applications

Power

Fuel cells are very useful as power sources in remote locations, such as spacecraft, remote weather stations, large parks, rural locations, and in certain military applications. A fuel cell system running on hydrogen can be compact and lightweight, and have no major moving parts. Because fuel cells have no moving parts and do not involve combustion, in ideal conditions they can achieve up to 99.9999% reliability.[43] This equates to less then one minute of downtime in a six year period.[44]

Stationary fuel cells are also used for commercial, industrial and residential primary and backup power generation. Fuel cells are used to power remote location research stations, communication centers etc. Since fuel cellelectrolyzer systems do not store fuel in themselves, but rather rely on external storage units, they can be successfully applied in large-scale energy storage, rural areas being one example.[45] There are many different types of stationary fuel cells so efficiencies vary, but most are between 40% and 60% energy efficient.[46] However, when the fuel cell’s waste heat is used to heat a building in a cogeneration system this efficiency jumps to 85%.[47] This is significantly more efficient than traditional coal power plants, which are only about 33% energy efficient.[48] Fuel cells can save 20-40% on energy costs when used in cogeneration systems.[49] Fuel cells are also much cleaner than traditional power generation; a fuel cell power plant using natural gas as a hydrogen source would create less than one ounce of pollution for every 1,000 kW produced, compared to 25 pounds of pollutants generated by conventional combustion systems.[50] Fuel Cells also produce 97% less nitrogen oxide emissions then conventional coal-fired power plants.

Coca-Cola, Google, Sysco, FedEx, UPS, Ikea, Staples, Whole Foods, Gills Onions, Nestle Waters, Pepperidge Farm, Sierra Nevada Brewery, Super Store Industries, Brigestone-Firestone, Nissan North America, Kimberly-Clark, Michelin and more have installed fuel cells to help meet their power needs.[51] One such pilot program is operating on Stuart Island in Washington State. There the Stuart Island Energy Initiative[52] has built a complete, closed-loop system: Solar panels power an electrolyzer which makes hydrogen. The hydrogen is stored in a 500 US gallons (1,900 L) at 200 pounds per square inch (1,400 kPa), and runs a ReliOn fuel cell to provide full electric back-up to the off-the-grid residence.

Cogeneration

Combined heat and power (CHP) fuel cell systems, including Micro combined heat and power (MicroCHP) systems are used to generation both electricity and heat for homes (see home fuel cell), office building and factories. These stationary fuel cells are already in the mass production phase. The system generates constant electric power (selling excess power back to the grid when it is not consumed), and at the same time produces hot air and water from the waste heat. MicroCHP is usually less than 5 kWe for a home fuel cell or small business.[53]

Co-generation system have efficiency around 85% (40-60% electric + remainder as thermal).[54] Phosphoric-acid fuel cells (PAFC) comprise the largest segment of existing CHP products worldwide and can provide combined efficiencies close to 90%.[55] Molten Carbonate (MCFC) and Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFC) are also used for combined heat and power generation and have electrical energy effciences around 60%. [56]

Fuel Cell Transportation Vehicles and Hydrogen refueling

Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs)

FCEV technology has advanced rapidly in the last few years, and is expected to begin mass commercialization in 2014/2015. As of June 2011 FCEVs had driven more than 3 million miles, with more than 27,000 successful refueling of hydrogen storage tanks.[57] Although one kg of hydrogen is roughly equivalent in energy to a gallon of gasoline, fuel cells are twice as efficient as traditional internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs), and so have to carry significantly less fuel.

Advancements continue to bring down the size, weight and cost of FCEVs. EERE’s Fuel Cell Technology Program helped achieve 59% FCEV efficiency, twice that of combustion vehicles, and a durability of over 75,000 miles with less than 10% degradation, double that achieved in 2006.[58] On a full tank of hydrogen, FCEVs can achieve ranges of more than 420 miles, although most cars currently being tested are in the 200-300 mile range, still comparable to, if not better than, many ICEVs.[59] Another storage benefit of FCEVs is the short, 3 minute refueling time. The cost of FCEVs has declined 30% since 2008 and 80% since 2002. [60]

In a Well-to-Wheels (WTW) analysis, the DOE found that FCEVs using hydrogen produced from natural gas emit less than half the CO2 per mile of an ICEV and had 25% less emissions than hybrids.[61] Fuel cell buses already deployed have a 40% higher fuel economy than diesel buses. [62] These efficiencies will only improve as we conduct further research and move to renewable hydrogen production. NREL found that the vast majority of counties in the U.S. have the potential to produce more renewable hydrogen for FCEVs than gas they consumed in 2002.[63] The DOE predicted in 20-30 years FCEVs will emit 10% less carbon and use 33% less BTUs than battery electric vehicles. [64]

Although there are currently no Fuel cell vehicles available for commercial sale over 20 FCEVs prototypes and demonstration cars have been released since 2009.[65] Chevrolet, Honda, Toyota, Mercedes Benz, Hyundai/Kia and others have all pledged to produce FCEVs for commercial sale in 2015. Mercedes Benz recently announced that it would move up the production of its B-Class F-Cell from 2015 to 2014.[66] Some notable releases in the last few years include:[67] -Hyundai Tuscon ix35 FCEV (2010) -Lotus Engineering Zero Emissions Black Cab (2010) -BMW 1 series fuel cell hybrid (2010) -Mercedes Benz F800 (2010) -Mazda 5 Hydrogen RE Hybrid (2009) -Fiat Panda HyTRAN (2009) -Audi Q5 FCEV (2009) -Nissan X-trail FCV (2009) -Volkwagen Caddy Maxi HyMotion (2009) -Mercedes benz B-Class F-Cell (2009) -Cadillac provoq (2008) -Toyota fchv-adv (2008) -Kia Borrego FCEV (2008) -GM HydroGen4 (2008) -Peugeot Citroen H2Origin (2008) -Geely Mk Fuel Cell (2008) -VW Tiguan HyMotion (2007) -Toyota FCHV (2007) -Ford Edge FCHV (2007)

The 2001 Chrysler Natrium used its own on-board hydrogen processor. It produces hydrogen for the fuel cell by reacting sodium borohydride fuel with Borax, both of which Chrysler claimed were naturally occurring in great quantity in the United States.[68] The hydrogen produces electric power in the fuel cell for near-silent operation and a range of 300 miles without impinging on passenger space. Chrysler also developed vehicles which separated hydrogen from gasoline in the vehicle, the purpose being to reduce emissions without relying on a nonexistent hydrogen infrastructure and to avoid large storage tanks.[69]

In 2005 the British firm Intelligent Energy produced the first ever working hydrogen run motorcycle called the ENV (Emission Neutral Vehicle). The motorcycle holds enough fuel to run for four hours, and to travel 100 miles in an urban area, at a top speed of 50 miles per hour.[70] In 2004 Honda developed a fuel-cell motorcycle which utilized the Honda FC Stack.[71][72]

In 2007, the Revolve Eco-Rally (launched by HRH Prince of Wales) demonstrated several fuel cell vehicles on British roads for the first time, driven by celebrities and dignitaries from Brighton to London's Trafalgar Square.[citation needed] Fuel cell powered race vehicles, designed and built by university students from around the world, competed in the world's first hydrogen race series called the 2008 Formula Zero Championship, which began on August 22, 2008 in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. More races are planned for 2009 and 2010. After this first race, Greenchoice Forze from the university of Delft (The Netherlands) became leader in the competition. Other competing teams are Element One (Detroit), HerUCLAs (LA), EUPLAtecH2 (Spain), Imperial Racing Green (London) and Zero Emission Racing Team (Leuven).

In 2008, Honda released a hydrogen vehicle, the FCX Clarity. Meanwhile there exist also other examples of bikes[73] and bicycles[74] with a hydrogen fuel cell engine.

In total there are over 100 fuel cell buses deployed around the world today. Most buses are produced by UTC Power, Toyota, Ballard, Hydrogenics, and Proton Motor. UTC Buses have already accumulated over 600,000 miles of of driving.[75] Fuel cell buses have a 30-141% higher fuel economy than diesel buses and natural gas buses.[76] Fuel cell buses have been deployed around the world including in Whistler Canada, San Francisco USA, Hamburg Germany, Shanghai China, London England, Sao Paulo Brazil as well as several others.[77] Notable Projects Include:

-12 Fuel cell buses are being deployed in AC transit buses being deployed in the Oakland and San Francisco Bay area of California.[78]

-Daimler AG, with thirty-six experimental units powered by Ballard Power Systems fuel cells completing a successful three-year trial, in eleven cities, in January 2007.[79][80]

-A fleet of Thor buses with UTC Power fuel cells in California, operated by SunLine Transit Agency.[81]

The Fuel Cell Bus Club is a global cooperative effort in trial fuel cell buses.

The first Brazilian hydrogen fuel cell bus prototype will begin operation in São Paulo during the first semester of 2009. The hydrogen bus was manufactured in Caxias do Sul and the hydrogen fuel will be produced in São Bernardo do Campo from water through electrolysis. The program, called "Ônibus Brasileiro a Hidrogênio" (Brazilian Hydrogen Autobus), includes three additional buses.[82][83]

Airplanes

Boeing researchers and industry partners throughout Europe conducted experimental flight tests in February 2008 of a manned airplane powered only by a fuel cell and lightweight batteries. The Fuel Cell Demonstrator Airplane, as it was called, used a Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) fuel cell/lithium-ion battery hybrid system to power an electric motor, which was coupled to a conventional propeller.[84] In 2003, the world's first propeller driven airplane to be powered entirely by a fuel cell was flown. The fuel cell was a unique FlatStackTM stack design which allowed the fuel cell to be integrated with the aerodynamic surfaces of the plane.[85]

There have been several fuel cell powered unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV). A Horizen fuel cell UAV set the record distance flow for a small UAV in 2007.[86] The military is especially interested in this application because of the low noise, low thermal signature and ability to attain high altitude. In 2009 the Naval Research Laboratory’s (NRL’s) Ion Tiger utilized a hydrogen-powered fuel cell and flew for 23 hours and 17 minutes.[87] Boeing is completing tests on the Phantom Eye, a high-altitude, long endurance (HALE) to be used to conduce research and surveillance flying at 65,000 ft for up to four days at a time.[88] Fuel ells are also being used to provide auxiliary power power aircraft, replacing fossil fuel generators that were previously used to start the engines and power on board electrical needs.[89] Fuel cells can help airplanes reduce CO2 and other pollutant emissions and noise.

Boats

The world's first Fuel Cell Boat HYDRA used an AFC system with 6.5 kW net output.

For each liter of fuel consumed, the average outboard motor produces 140 times the hydrocarbonss produced by the average modern car. Fuel cell engines have higher energy efficiencies than combustion engines, and therefore offer better range and significantly reduced emissions.[90] Iceland has committed to converting its vast fishing fleet to use fuel cells to provide auxiliary power by 2015 and, eventually, to provide primary power in its boats. Amsterdam recently introduced its first fuel cell powered boat that ferries people around the city's famous and beautiful canals. [91]

Submarines

The Type 212 submarines of the German and Italian navies use fuel cells to remain submerged for weeks without the need to surface.

The latest in fuel cell submarines is the U212A -- an ultra-advanced non-nuclear sub developed by German naval shipyard Howaldtswerke Deutsche Werft, who claim it to be "the peak of German submarine technology."[92] The system consists of nine PEM (polymer electrolyte membrane) fuel cells, providing between 30kW and 50kW each. The ship is totally silent giving it a distinct advantage in the detection of other submarines. [93] Fuel cells offer some distinct advantages to submarines, in addition to being completely silent, and can be distributed throughut a ship to improve balance and require far less air to run, allowing ships to be submerged for longer periods of time. Fuel cells offer a good alternative to nuclear fuels.

Fueling stations

The first public hydrogen refueling station was opened in Reykjavík, Iceland in April 2003. This station serves three buses built by DaimlerChrysler that are in service in the public transport net of Reykjavík. The station produces the hydrogen it needs by itself, with an electrolyzing unit (produced by Norsk Hydro), and does not need refilling: all that enters is electricity and water. Royal Dutch Shell is also a partner in the project. The station has no roof, in order to allow any leaked hydrogen to escape to the atmosphere.

The California Hydrogen Highway is an initiative by the California Governor to implement a series of hydrogen refueling stations along that state. These stations are used to refuel hydrogen vehicles such as fuel cell vehicles and hydrogen combustion vehicles. As of July 2007 California had 179 fuel cell vehicles and twenty five stations in operation,[94] and ten more stations have been planned for assembly in California. However, there have already been three hydrogen fueling stations decommissioned.[95]

South Carolina also has a hydrogen freeway in the works. There are currently two hydrogen fueling stations, both in Aiken and Columbia, SC. Additional stations are expected in places around South Carolina such as Charleston, Myrtle Beach, Greenville, and Florence. According to the South Carolina Hydrogen & Fuel Cell Alliance, the Columbia station has a current capacity of 120 kg a day, with future plans to develop on-site hydrogen production from electrolysis and reformation. The Aiken station has a current capacity of 80 kg. There is extensive funding for Hydrogen fuel cell research and infrastructure in South Carolina. The University of South Carolina, a founding member of the South Carolina Hydrogen & Fuel Cell Alliance, received 12.5 million dollars from the United States Department of Energy for its Future Fuels Program.[96]

Japan also has a hydrogen highway, as part of the Japan hydrogen fuel cell project. Twelve hydrogen fueling stations have been built in 11 cities in Japan. Canada, Sweden and Norway also have hydrogen highways implemented.

Other applications

- Providing power for base stations or cell sites[97][98]

- Off-grid power supply

- Distributed generation

- Fork Lifts

- Emergency power systems are a type of fuel cell system, which may include lighting, generators and other apparatus, to provide backup resources in a crisis or when regular systems fail. They find uses in a wide variety of settings from residential homes to hospitals, scientific laboratories, data centers,[99] telecommunication[100] equipment and modern naval ships.

- An uninterrupted power supply (UPS) provides emergency power and, depending on the topology, provide line regulation as well to connected equipment by supplying power from a separate source when utility power is not available. Unlike a standby generator, it can provide instant protection from a momentary power interruption.

- Base load power plants

- Electric and hybrid vehicles.

- Notebook computers for applications where AC charging may not be available for weeks at a time.

- Portable charging docks for small electronics (e.g. a belt clip that charges your cell phone or PDA).

- Smartphones with high power consumption due to large displays and additional features like GPS might be equipped with micro fuel cells.

- Small heating appliances [101]

- Space Shuttles

Market structure

Not all geographic markets are ready for SOFC powered m-CHP appliances. Currently, the regions that lead the race in Distributed Generation and deployment of fuel cell m-CHP units are the EU and Japan.[102]

Fuel cell economics

Use of hydrogen to fuel vehicles would be a critical feature of a hydrogen economy. A fuel cell and electric motor combination is not directly limited by the Carnot efficiency of an internal combustion engine.

Low temperature fuel cell stacks proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC), direct methanol fuel cell (DMFC) and phosphoric acid fuel cell (PAFC) use a platinum catalyst. Impurities create catalyst poisoning (reducing activity and efficiency) in these low-temperature fuel cells, thus high hydrogen purity or higher catalyst densities are required.[103] Although there are sufficient platinum resources for future demand,[104] most predictions of platinum running out and/or platinum prices soaring do not take into account effects of reduction in catalyst loading and recycling. Recent research at Brookhaven National Laboratory could lead to the replacement of platinum by a gold-palladium coating which may be less susceptible to poisoning and thereby improve fuel cell lifetime considerably.[105] Another method would use iron and sulphur instead of platinum. This is possible through an intermediate conversion by bacteria. This would lower the cost of a fuel cell substantially (as the platinum in a regular fuel cell costs around $1500, and the same amount of iron costs only around $1.50). The concept is being developed by a coalition of the John Innes Centre and the University of Milan-Bicocca.[106] PEDOT cathodes are immune to monoxide poisoning.[107]

Current targets for a transport PEM fuel cells are 0.2 g/kW Pt – which is a factor of 5 decrease over current loadings – and recent comments from major original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) indicate that this is possible. Recycling of fuel cells components, including platinum, will conserve supplies. High-temperature fuel cells, including molten carbonate fuel cells (MCFC's) and solid oxide fuel cells (SOFC's), do not use platinum as catalysts, but instead use cheaper materials such as nickel and nickel oxide. They also do not experience catalyst poisoning by carbon monoxide, and so they do not require high-purity hydrogen to operate. They can use fuels with an existing and extensive infrastructure, such as natural gas, directly, without having to first reform it externally to hydrogen and CO followed by CO removal.

Research and development

- August 2005: Georgia Institute of Technology researchers use triazole to raise the operating temperature of PEM fuel cells from below 100 °C to over 125 °C, claiming this will require less carbon-monoxide purification of the hydrogen fuel.[108]

- 2008 Monash University, Melbourne uses PEDOT as a cathode.[12]

- 2009 Researchers at the University of Dayton, in Ohio, have shown that arrays of vertically grown carbon nanotubes could be used as the catalyst in fuel cells.[109]

- 2009: Y-Carbon has begun to develop a carbide-derived-carbon-based ultracapacitor with high energy density which may lead to improvements in fuel cell technology.[110][111]

- 2009: A nickel bisdiphosphine-based catalyst for fuel cells is demonstrated.[112]

See also

- Bio-nano generator

- Comparison of automobile fuel technologies

- Cryptophane

- Energy development

- Fuel Cell Development Information Center

- Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Joint Technology Initiative (in Europe)

- Glossary of fuel cell terms

- Grid energy storage

- Hydrogen codes and standards

- Hydrogen reformer

- Hydrogen sulfide sensor

- Hydrogen storage

- Hydrogen technologies

- Microgeneration

- Paper battery

- Renewable energy

- Water splitting

References

- ^ "Batteries, Supercapacitors, and Fuel Cells: Scope". Science Reference Services. 20 August 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ S. G. Meibuhr, Electrochim. Acta, 11, 1301 (1966)

- ^ Larminie, James (1 May 2003). Fuel Cell Systems Explained, Second Edition. SAE International. ISBN 0768012597.

- ^ Anne-Claire Dupuis, Progress in Materials Science, Volume 56, Issue 3, March 2011, Pages 289-327

- ^ Kakati, B.K., Deka, D., “Effect of resin matrix precursor on the properties of graphite composite bipolar plate for PEM fuel cell”, Energy & Fuels 2007, 21 (3):1681–1687.

- ^ "LEMTA - Our fuel cells". Perso.ensem.inpl-nancy.fr. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ^ Kakati B.K., Mohan V., “Development of low cost advanced composite bipolar plate for P.E.M. fuel cell”, Fuel Cells 2008, 08(1): 45–51

- ^ Kakati B.K., Deka D., “Differences in physico-mechanical behaviors of resol and novolac type phenolic resin based composite bipolar plate for proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cell”, Electrochimica Acta 2007, 52 (25): 7330–7336.

- ^ http://www1.eere.energy.gov/hydrogenandfuelcells/pdfs/tiax_cost_analysis_pres.pdf

- ^ Fuel cell system cost

- ^ "Ballard Power Systems: Commercially Viable Fuel Cell Stack Technology Ready by 2010". 2005-03-29. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Online, Science (2008-08-02). "2008 - Cathodes in fuel cells". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ^ Template:Cite http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ja1112904?journalCode=jacsat

- ^ EP patent 0950075, "Electrolytic Membrane, Method of Manufacturing it and Use", published 1999-10-20, issued 2003-02-12, assigned to DSM

- ^ "Ballard Uses Solupor". 2005-09-13. Archived from the original on September 5, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Water_and_Air_Management". Ika.rwth-aachen.de. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ^ "Fuel Cell School Buses: Report to Congress" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ^ Hayashi, K., O. Yamamoto, H. Minoura. (2000) Portable solid oxide fuel cells using butane gas as fuel. Solid State Ionics, No. 302 pp. 343-345

- ^ Electricity from wood through the combination of gasification and solid oxide fuel cells, Ph.D. Thesis by Florian Nagel, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, 2008

- ^ Sahibzada, M., B. Steel, K. Hellgardt, D. Barth, A. Effendi, D. Mantzavinos, I. Metcalfe. (2000) Intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cells operated with methanol fuels. Chemical Engineering Science, No. 55: pp. 3077-3083

- ^ http://www1.eere.energy.gov/hydrogenandfuelcells/fuelcells/fc_types.html?m=1&

- ^ http://www.ceramicindustry.com/Articles/Feature_Article/10637442bbac7010VgnVCM100000f932a8c0____

- ^ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378775308002243

- ^ Milewski J. Lewandowski J. Miller A. Reducing CO2 emission from a coal fired power plant by using a molten carbonate fuel cell. Chemical and Process Engineering 30 (2009) 341-350

- ^ Milewski J. Lewandowski J. Miller A. Reducing CO2 Emissions From A Gas Turbine Power Plant By Using A Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell. Chemical and Process Engineering 29 (2008) 939-954

- ^ George Wand. "Fuel Cells History, part 1" (PDF). Johnson Matthey plc. p. 14. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

In January of 1839 the German/Swiss chemist Christian Friedrich Schönbein wrote an article in one of the scientific magazines of the time about his discovery of ozone and about the reaction of hydrogen and oxygen. But it was no other than William Grove to document just one month later, in February of 1839, his observations in the "Philosophical Magazine". He had conducted a series of experiments with his second invention which he termed a "gas voltaic battery".

- ^ Grove, William Robert "On Voltaic Series and the Combination of Gases by Platinum", Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science vol. XIV (1839), pp 127-130.

- ^ Grove, William Robert "On a Gaseous Voltaic Battery", Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science vol. XXI (1842), pp 417-420.

- ^ "Roger Billings Biography". International Association for Hydrogen Energy. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ^ "The PureCell 200 - Product Overview". UTC Power. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ "Apollo Space Program Hydrogen Fuel Cells". Spaceaholic.com. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ^ Kunze, Julia (2009). "Electrochemical Versus Heat-Engine Energy Technology: A Tribute to Wilhelm Ostwald's Visionary Statements". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 48 (49): 9230–9237. doi:10.1002/anie.200903603. PMID 19894237.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ "Fuel Cell efficiency". Worldenergy.org. 2007-07-17. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ^ "About Fuel Cells". MIT / NASA. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ Milewski J. Miller A. Sałacinski J. Off-Design Analysis of SOFC Hybrid System International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 32 (2007) 687-698

- ^ Milewski J. Swiercz T. Badyda K. Miller A. Dmowski A. Biczel P. The control strategy for a molten carbonate fuel cell hybrid system. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, In Press

- ^ Eberle, Ulrich; von Helmolt, Rittmar (2010-05-14). "Sustainable transportation based on electric vehicle concepts: a brief overview". Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ^ Von Helmolt, R; Eberle, U (2007-03-20). "Fuel Cell Vehicles:Status 2007". Journal of Power Sources. 165: 833. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2006.12.073.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Honda FCX Clarity - Fuel cell comparison". Honda. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ "Efficiency of Hydrogen PEFC, Diesel-SOFC-Hybrid and Battery Electric Vehicles" (PDF). 2003-07-15. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ^ More than 90% of all hydrogen is produced by SMR

- ^ "Round Trip Energy Efficiency of NASA Glenn Regenerative Fuel Cell System". Preprint. 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Fuel Cell Basics: Benefits". Fuel Cells 2000. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ http://www.fuelcells.org/basics/benefits.html

- ^ http://www.fuelcells.org/basics/apps.html

- ^ http://www1.eere.energy.gov/hydrogenandfuelcells/fuelcells/fc_types.html

- ^ http://www1.eere.energy.gov/hydrogenandfuelcells/fuelcells/fc_types.html

- ^ http://www.energy.gov/energysources/electricpower.htm

- ^ http://www1.eere.energy.gov/hydrogenandfuelcells/pdfs/48219.pdf

- ^ U.S. Fuel Cell Council- Industry Overview 2010 pg 12

- ^ http://www.fuelcells.org/BusinessCaseforFuelCells.pdf

- ^ "Stuart Island Energy Initiative". Siei.org. Retrieved 2009-09-21. - gives extensive technical details

- ^ COGEN EUROPE

- ^ http://www1.eere.energy.gov/hydrogenandfuelcells/fuelcells/fc_types.html

- ^ http://www.utcpower.com/products/purecell400

- ^ http://www1.eere.energy.gov/hydrogenandfuelcells/fuelcells/pdfs/fc_comparison_chart.pdf

- ^ http://www.nrel.gov/hydrogen/pdfs/46679.pdf

- ^ http://www1.eere.energy.gov/hydrogenandfuelcells/accomplishments.html

- ^ http://www1.eere.energy.gov/hydrogenandfuelcells/accomplishments.html

- ^ http://www1.eere.energy.gov/hydrogenandfuelcells/accomplishments.html

- ^ “Distributed Hydrogen Production via Steam Methane Reforming” case study http://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/well_wheels_analysis.html

- ^ DOE Hydrogen Program FY 2010 annual progress report: VIII.0 Technology Validation Sub-Program Overview http://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/pdfs/progress10/viii_0_technology_validation_overview.pdf

- ^ http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy07osti/41134.pdf

- ^ DOE http://hydrogen.energy.gov/pdfs/10001_well_to_wheels_gge_petroleum_use.pdf

- ^ http://www.netinform.net/H2/H2Mobility/Default.aspx?ID=431&CATID=0

- ^ http://www.insideline.com/mercedes-benz/mercedes-benz-fuel-cell-car-ready-for-market-in-2014.html

- ^ http://www.netinform.net/H2/H2Mobility/Default.aspx?ID=431&CATID=0

- ^ "natrium". Allpar.com. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ^ "Chrysler Fuel Cell Vehicles". allpar.com. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ "The ENV Bike". Intelligent Energy. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ "Honda Develops Fuel Cell Scooter Equipped with Honda FC Stack". Honda Motor Co. 2004-08-24. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ Bryant, Eric (2005-07-21). "Honda to offer fuel-cell motorcycle". autoblog.com. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ 15. Dezember 2007. "Hydrogen Fuel Cell electric bike". Youtube.com. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.horizonfuelcell.com Horizon fuel cell vehicles

- ^ http://www.utcpower.com/products/transportation/fleet-vehicles

- ^ DOE Hydrogen Program FY 2010 annual progress report: VIII.0 Technology Validation Sub-Program Overview http://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/pdfs/progress10/viii_0_technology_validation_overview.pdf

- ^ http://www.calstart.org/projects/low-carbon-bus-program/National-Fuel-Cell-Bus-Program/National-Fuel-Cell-Bus-Program-Awards.aspx

- ^ http://www.calstart.org/projects/low-carbon-bus-program/National-Fuel-Cell-Bus-Program/National-Fuel-Cell-Bus-Program-Awards.aspx

- ^ "European Fuel Cell Bus Project Extended by One Year". DaimlerChrysler. Retrieved 2007-03-31.[dead link]

- ^ "Fuel cell buses". Transport for London. Archived from the original on May 13, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "UTC Power - Fuel Cell Fleet Vehicles".[dead link]

- ^ "Ônibus brasileiro movido a hidrogênio começa a rodar em São Paulo" (in Portuguese). Inovação Tecnológica. 2009-04-08. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ^ "Ônibus a Hidrogênio vira realidade no Brasil" (in Portuguese). Inovação Tecnológica. Abril 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) [dead link] - ^ "Boeing Successfully Flies Fuel Cell-Powered Airplane".

- ^ First Fuel Cell Microaircraft First Fuel Cell Microaircraft

- ^ http://www.horizonfuelcell.com/file/Pterosoardistancerecord.pdf,

- ^ http://www.alternative-energy-news.info/fuel-cell-powered-uav-flight/

- ^ http://www.theengineer.co.uk/sectors/aerospace/news/hydrogen-powered-unmanned-aircraft-completes-set-of-tests/1009080.article

- ^ http://www.theengineer.co.uk/in-depth/analysis/hydrogen-in-the-air-electric-aircraft/1009063.article

- ^ http://www.fuelcells.org/basics/apps.html

- ^ http://www.lovers.nl/co2zero/

- ^ http://articles.cnn.com/2011-02-22/tech/hybrid.submarine_1_submariners-aircraft-carrier-howaldtswerke-deutsche-werft?_s=PM:TECH

- ^ http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/type_212/

- ^ "California Fuel Cell Partnership".

- ^ "Hydrogen Fueling Stations".[dead link]

- ^ Cluster Successes in South Carolina

- ^ Ballard fuel cells to power telecom backup power units for motorola

- ^ India telecoms to get fuel cell power

- ^ Fuel cell in the data center Munich

- ^ India orders 10.000 fuel cell emergency power systems

- ^ DVGW VP 119 Brennstoffzellen-Gasgeräte bis 70 kW (German)

- ^ "m-CHP". Cfcl.com.au. Archived from the original on September 14, 2007. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Faur-Ghenciu, Anca (April/May 2003). "Fuel Processing Catalysts for Hydrogen Reformate Generation for PEM Fuel Cells" (PDF). FuelCell Magazine. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[dead link] - ^ International Platinum Group Metals Association-FAQ

- ^ Johnson, R. Colin (2007-01-22). "Gold is key to ending platinum dissolution in fuel cells". EETimes.com. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ Replacement of platinum by iron-sulpher

- ^ Fuel cell improvements raise hopes for clean, cheap energy

- ^ "Chemical Could Revolutionize Polymer Fuel Cells". Georgia Institute of Technology. 2005-08-24. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ Cheaper fuel cells

- ^ Lane, K. (2009, September). Y-carbon? because it has so many applications!. NanoMaterials Quarterly, Retrieved from http://www.y-carbon.us/Portals/0/docs/Media/Newsletter_september_2009.pdf

- ^ Savage, N. (2009, October). Nanoporous carbon could help power hybrid cars. Technology Review, 112(5), 51, Retrieved from http://www.y-carbon.us/Portals/0/docs/Media/TR35.pdf

- ^ Bio-inspired catalyst design could rival platinum

Further reading

- Vielstich, W., et al. (eds.) (2009). Handbook of fuel cells: advances in electrocatalysis, materials, diagnostics and durability. 6 vol. Hoboken: Wiley, 2009.

- Gregor Hoogers (2003). Fuel Cell Technology – Hand Book. CRC Press.

- James Larminie and Andrew Dicks (2003). Fuel Cell Systems Explained, 2nd Edition. John Wiley and Sons.

- High Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells-Fundamentals, Design and Applications. Elsevier. 2003.

- Frano Barbir. PEM Fuel Cells-Theory and Practice. Elsevier Academic Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - EG&G Technical Services, Inc. (2004). Fuel Cell Technology-Hand book, 7th Edition. U.S. Department of Energy.

- Matthew M. Mench (2008). Fuel Cell Engines. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

External links

- Fuel Cell Origins: 1840-1890

- TC 105 IEC Technical standard for Fuel Cells

- EERE: Hydrogen, Fuel Cells and Infrastructure Technologies Program

- Thermodynamics of electrolysis of water and hydrogen fuel cells

- 2002-PORTABLE POWER APPLICATIONS OF FUEL CELLS

- US Fuel Cell Council

- DoITPoMS Teaching and Learning Package- "Fuel Cells"

- Animation how a fuel cell works