Trojan Horse

The Trojan Horse is a tale from the Trojan War, as told in Virgil's Latin epic poem The Aeneid, also by Dionysius, Apollodorus and Quintus of Smyrna. The events in this story from the Bronze Age took place after Homer's Iliad, and before his Odyssey. It was the stratagem that allowed the Greeks finally to enter the city of Troy and end the conflict.

In one version, after a fruitless 10-year siege, the Greeks constructed a huge wooden horse, and hid a select force of 30 men inside. The Greeks pretended to sail away, and the Trojans pulled the horse into their city as a victory trophy. That night the Greek force crept out of the horse and opened the gates for the rest of the Greek army, which had sailed back under cover of night. The Greek army entered and destroyed the city of Troy, decisively ending the war.

In the Greek tradition, the horse is called Δούρειος Ἵππος, Doúreios Híppos, the "Wooden Horse", in the Homeric Ionic dialect. Metaphorically a "Trojan Horse" has come to mean any trick or stratagem that causes a target to invite a foe into a securely protected bastion or space. It is also associated with "malware" computer programs presented as useful or harmless to induce the user to install and run them.

Literary accounts

According to Quintus Smyrnaeus, Odysseus came up with the idea of building a great wooden horse (the horse being the emblem of Troy), hiding a select force inside, and fooling the Trojans into wheeling the horse into the city as a trophy. Under the leadership of Epeios, the Greeks built the wooden horse in three days. Odysseus' plan called for one man to remain outside of the horse; he would act as though the Greeks abandoned him, leaving the horse as a gift for the Trojans. A Greek soldier named Sinon was the only volunteer for the role. Virgil describes the actual encounter between Sinon and the Trojans: Sinon successfully convinces the Trojans that he has been left behind and that the Greeks are gone. Sinon tells the Trojans that the Horse is an offering to the goddess Athena, meant to atone for the previous desecration of her temple at Troy by the Greeks, and ensure a safe journey home for the Greek fleet. The Horse was built on such a huge size to prevent the Trojans from taking the offering into their city, and thus garnering the favor of Athena for themselves.

While questioning Sinon, the Trojan priest Laocoön guesses the plot and warns the Trojans, in Virgil's famous line "Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes" (I fear Greeks even those bearing gifts).[1](original:Φοβού τους Δαναούς και δώρας φέρονταις) which became known as 'beware of Greeks bearing gifts".Danaos been the ones who build the Trojan Horse, However, the god Poseidon sent two sea serpents to strangle him and his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus, before any Trojan believes his warning. According to Apollodorus it was Apollo who sent the two serpents since Laocoon had insulted Apollo by sleeping with his wife in front of the "divine image".[2] Helen of Troy also guesses the plot and tries to trick and uncover the Greek men inside the horse by imitating the voices of their wives. Anticlus would have answered, but Odysseus shut his mouth with his hand.[3] King Priam's daughter Cassandra, the soothsayer of Troy, insists that the horse would be the downfall of the city and its royal family. She too is ignored, hence their doom and loss of the war.[4]

| Trojan War |

|---|

|

This incident is mentioned in the Odyssey:

- What a thing was this, too, which that mighty man wrought and endured in the carven horse, wherein all we chiefs of the Argives were sitting, bearing to the Trojans death and fate! 4.271 ff

- But come now,change thy theme, and sing of the building of the horse of wood, which Epeius made with Athena's help, the horse which once Odysseus led up into the citadel as a thing of guile, when he had filled it with the men who sacked Ilion . 8.487 ff (trans. Samuel Butler)

The most detailed and most familiar version is in Virgil's Aeneid, Book II [1] (trans. A. S. Kline]]).

After many years have slipped by, the leaders of the Greeks,

opposed by the Fates, and damaged by the war,

build a horse of mountainous size, through Pallas’s divine art,

and weave planks of fir over its ribs:

they pretend it’s a votive offering: this rumour spreads.

They secretly hide a picked body of men, chosen by lot,

there, in the dark body, filling the belly and the huge

cavernous insides with armed warriors.

[...]

Then Laocoön rushes down eagerly from the heights

of the citadel, to confront them all, a large crowd with him,

and shouts from far off: ‘O unhappy citizens, what madness?

Do you think the enemy’s sailed away? Or do you think

any Greek gift’s free of treachery? Is that Ulysses’s reputation?

Either there are Greeks in hiding, concealed by the wood,

or it’s been built as a machine to use against our walls,

or spy on our homes, or fall on the city from above,

or it hides some other trick: Trojans, don’t trust this horse.

Whatever it is, I’m afraid of Greeks even those bearing gifts.’

Book II includes Laocoön saying: "Equo ne credite, Teucri. Quidquid id est, timeo Danaos et dona ferentes." ("Do not trust the horse, Trojans! Whatever it is, I fear the Greeks, even bringing gifts.") This is the origin of the modern adage "Beware of Greeks bearing gifts".

Men in the horse

Thirty soldiers hid in the Trojan horse's belly and two spies in its mouth. Other sources give different numbers: Apollodorus 50;[5] Tzetzes 23;[6] and Quintus Smyrnaeus gives the names of thirty, but says there were more.[7] In late tradition the number was standardized at 40. Their names follow:[8]

- Odysseus (leader)

- Acamas

- Agapenor

- Ajax the Lesser

- Amphidamas

- Amphimachus

- Anticlus

- Antimachus

- Antiphates

- Calchas

- Cyanippus

- Demophon

- Diomedes

- Echion

- Epeius

- Eumelus

- Euryalus

- Eurydamas

- Eurymachus

- Eurypylus

- Ialmenus

- Idomeneus

- Iphidamas

- Leonteus

- Machaon

- Meges

- Menelaus

- Menestheus

- Meriones

- Neoptolemus

- Peneleus

- Philoctetes

- Podalirius

- Polypoetes

- Sthenelus

- Teucer

- Thalpius

- Thersander

- Thoas

- Thrasymedes

Factual explanations

According to Homer, Troy stood overlooking the Hellespont – a channel of water that separates Asia Minor and Europe. In the 1870s, Heinrich Schliemann set out to find it.[9] Following Homer's description, he started to dig at Hisarlik in Turkey and uncovered the ruins of several cities, built one on top of the other. Several of the cities had been destroyed violently, but it is not clear which, if any, was Homer's Troy.

Pausanias, who lived in the 2nd century AD, wrote in his book Description of Greece "That the work of Epeius was a contrivance to make a breach in the Trojan wall is known to everybody who does not attribute utter silliness to the Phrygians"[10] where by Phrygians he means the Trojans.

There has been modern speculation that the Trojan Horse may have been a battering ram resembling, to some extent, a horse, and that the description of the use of this device was then transformed into a myth by later oral historians who were not present at the battle and were unaware of that meaning of the name. Assyrians at the time used siege machines with animal names; it is possible that the Trojan Horse was such.[11]

It has also been suggested that the Trojan Horse actually represents an earthquake that occurred between the wars that could have weakened Troy's walls and left them open for attack;[12] the deity Poseidon had a triple function as a god of the sea, of horses and of earthquakes. Structural damage on Troy VI – its location being the same as that represented in Homer's Iliad and the artifacts found there suggesting it was a place of great trade and power – shows signs that there was indeed an earthquake. Generally, though, Troy VIIa is believed to be Homer's Troy (see below).

Some authors have suggested that the gift was not a horse warriors hiding in her side, but a boat carrying a peace envoy,[13] and it has also been noted that the terms used to put men in the horse are those used when describing the embarkation of men on a ship.[14]

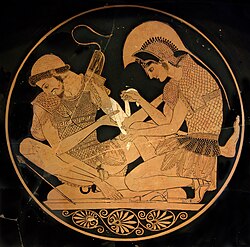

Images

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2010) |

There are three known surviving classical depictions of the Trojan horse. The earliest is on a fibula brooch dated about 700 BC. The other two are on relief pithos vases from the adjoining Grecian islands Mykonos and Tinos, both usually dated between 675 and 650 BC, the one from Mykonos being known as the Mykonos Vase.[15][16] Historian Michael Wood, however, dates the Mykonos Vase to the 8th century BC, some 500 years after the supposed time of the war, but before the written accounts attributed by tradition to Homer. Wood concludes from that evidence that the story of the Trojan Horse was in existence prior to the writing of those accounts.[17]

-

From the movie Troy

Notes

- ^ Virgil:Aeneid II

- ^ Apollodorus, Epitome, Epit. E.5.18

- ^ Homer, Odyssey, 4. 274-289.

- ^ Virgil. The Aeneid. Trans. Robert Fitzgerald. New York: Everyman's Library, 1992. Print.

- ^ Epitome 5.14

- ^ Posthomerica 641–650

- ^ Posthomerica xii.314-335

- ^ THE WOODEN HORSE - Greek Mythology Link

- ^ Image

- ^ 1,XXIII,8

- ^ Michael Wood, in his book "In search of the Trojan war" ISBN 978-0520215993 (which was shown on BBC TV as a series)

- ^ Earthquakes toppled ancient cities: 11/12/97

- ^ See pages 51-52 inTroy C. 1700-1250 BC,Nic Fields, Donato Spedaliere & Sarah S. Spedalier, Osprey Publishing, 2004

- ^ See pages 22-23 in The fall of Troy in early Greek poetry and art, Michael John Anderson, Oxford University Press, 1997

- ^ Sparks, B.A. (1971). "The Trojan Horse in Classical Art". Greece & Rome. Second series. 18 (1): 54–70. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Caskey, Miriam Ervin (1976). "Notes on Relief Pithoi of the Tenian-Boiotian Group". American Journal of Archaeology. 80 (1): 19–41. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wood, Michael (1985). In Search of the Trojan War. London: BBC books. pp. 80, 251. ISBN 9780563201618.

External links

![]() Media related to Trojan horse at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Trojan horse at Wikimedia Commons