Germanisation

Germanisation (also spelled Germanization) is both the spread of the German language, people and culture either by force or assimilation, and the adaptation of a foreign word to the German language in linguistics, much like the Romanisation of many languages which do not use the Latin alphabet. It was a central plank of German liberal thinking in the early nineteenth century, at a period when liberalism and nationalism went hand-in-hand.

Forms of Germanisation

Historically, there are very different forms and degrees of expansion of German language and elements of German culture. There are examples of complete assimilation into German culture, as it happened with the pagan Slavs in the diocese of Bamberg in the 11th century.[citation needed] A perfect example of eclectic adoption of German culture is the field of law in Imperial and present-day Japan, which is organised very much to the model of the German Empire.[citation needed] Germanisation took place by cultural contact, by political decision of the adopting party (e.g. in the case of Japan), or (especially in the case of Imperial and Nazi Germany) by force.

In Slavic countries, the term Germanisation is often understood solely as the process of acculturation of Slavic and Baltic speakers, after the conquests or by cultural contact in the early Dark Ages, areas of the modern Eastern Germany to the line of the Elbe.[citation needed] In East Prussia, forced resettlement of the Prussian people by the Teutonic Order and the Prussian state, as well as acculturation from immigrants of various European countries (Poles, French and Germans) contributed to the eventual extinction of the Prussian language in the 17th century.

Another form of Germanisation is the forceful imposition of German culture, language and people upon non-German people, Slavs in particular.

Historical Germanisation

Early

Early Germanisation went along with the Ostsiedlung during the Middle Ages, e.g. in Hanoverian Wendland, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lusatia, and other areas, formerly inhabited by Slavic tribes - Polabian Slavs such as Obotrites, Veleti and Sorbs. Relations of early forms of Germanisation was described by German monks in manuscripts like Chronicon Slavorum.

Lüchow-Dannenberg is better known as the Wendland, a designation referring to the Slavic people of the Wends from the Slavic tribe Drevani — the Polabian language survived until the beginning of the 19th century in what is now the German state of Lower Saxony.[1]

A complex process of Germanisation took place in Bohemia after the defeat of Bohemian Protestants at the Battle of White Mountain in 1620. The German prince and Frederick V, Elector Palatine, elected as king of Bohemia by the Bohemian estates in 1619, was defeated by Catholic forces loyal to the Habsburg Emperor, Ferdinand II. Among the Bohemian lords who were punished and had their lands expropriated after Frederick's defeat in 1620 were German- and Czech-speaking landowners. Thus, this conflict was feudal in nature, not national. Although the Czech language lost its significance as a written language in the aftermath of the events, it is doubtful that this was intended by the Habsburg rulers, whose aims were of a feudal and religious character

In Tyrol there was a germanisation of the ladino-romantsch of the Venosta Valley (now Italy) promoted by the Austria in the XVI century. There was made for avoiding contact with protestants of the Grigioni canton.

Linguistic influences

The rise of nationalism that occurred in the late 18th and 19th centuries in Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Pomerania, Lusatia, and Slovenia led to an increased sense of "pride" in national cultures during this time. However, centuries of cultural dominance of the Germans left a German mark on those societies; for instance, the first modern grammar of the Czech language by Josef Dobrovský (1753–1829) – "Ausführliches Lehrgebäude der böhmischen Sprache" (1809) – was published in German because the Czech language was not used in academic scholarship.

In the German colonies, the policy of having German as an official language led to the forming of German-based pidgins and German-based creole languages, such as Unserdeutsch.

In the Austrian Empire

Joseph II (1780–90), a leader influenced by the Enlightenment, sought to centralise control of the empire and to rule it as an enlightened despot.[2] He decreed that German replace Latin as the empire's official language.[2]

Hungarians perceived Joseph's language reform as German cultural hegemony, and they reacted by insisting on the right to use their own tongue.[2] As a result, Hungarian lesser nobles sparked a renaissance of the Hungarian language and culture.[2] The lesser nobles questioned the loyalty of the magnates, of whom less than half were ethnic Magyars, and even those had become French- and German-speaking courtiers.[2] The Magyar national revival subsequently triggered similar movements among the Slovak, Romanian, Serbian, and Croatian minorities within the Kingdom of Hungary.[2]

In Tyrol there was a second operation of Germanisation (the first was in the 16th century) between the 19th and 20th centuries prohibiting the teaching of the Italian and Ladin languages in the school.[citation needed] The only language accepted and allowed was German.

In Prussia

Germanisation in Prussia occurred in several stages:

- Germanisation attempts pursued by Frederick the Great in territories of Partitioned Poland

- Easing of Germanisation policy in the period 1815–30

- Intensification of Germanisation and persecution of Poles in the Grand Duchy of Posen by E.Flotwell in 1830–41

- The process of Germanisation ceases during the period of 1841–49

- Restarted during years of 1849–70

- Intensified by Bismarck during his Kulturkampf against Catholicism and Polish people

- Slight easing of the persecution of Poles during 1890–94

- Continuation and intensification of activity restarted in 1894 and pursued till the end of World War I

Legislation and government policies in the Kingdom of Prussia sought a degree of linguistic and cultural Germanisation, while in the Imperial Germany a more intense form of cultural Germanisation was pursued, often with the explicit intention of reducing the influence of other cultures or institutions, such as the Catholic Church. In Nazi Germany, however, the eradication of non-German cultures and languages was pursued through deportations, resettlement and the physical extermination of non-German populations.[citation needed]

Situation in the 18th century

When judging Germanisation, one has to decide whether this was seen as an act of ameliorating the economy of the country or the aim of repressing or eliminating the local language and culture. Settlers from all over Europe were invited to settle Prussia under the kings Frederick I, Frederick William I., and Frederick the Great. The settlements were planned either in sparsely populated areas, in areas which had been reclaimed (e. g. after drying up the Oderbruch swamp under Frederick the Great), or in areas that had been depopulated by war or plague (e. g. the settlement of the Protestants expelled from the Archbishopric of Salzburg in East Prussia 1731/32 under king Frederick William I.).[citation needed] Additionally, several 10.000 French Protestant refugees granted asylum in Prussia after the renouncement of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Around 1700 about half of the people of Berlin actually spoke French and the French community in Berlin used the French language in their services until 1807, when they decided to give it up and use German instead to protest against the occupation of Prussia by Napoléon.[citation needed] These settlements were not intended as a means of Germanisation but rather an instrument of bringing the economy of Prussia to a more advanced stage, much in the same way Slavonian rulers invited German settlers into their countries in the Middle Ages. Nationality was not especially important to Frederick the Great. To underline his religious tolerance he once stated that "if Turks want to come and settle here we will build mosques for them".[citation needed] Germanisation was not the primary intention of these settlements, although it may have been a side effect.

Prussia was one of the first countries in Europe to introduce compulsory primary school attendance under Frederick William I. Among the principal motivations was religious education; it was believed that if people were able to read the Bible it would make "good Christians" out of them.[citation needed] Education in primary school was carried out in the prevailing language of the area and thus primary school was not a tool of Germanisation in the 18th century.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, Prussia and Austria actively participated in the partitions of Poland, a fact that would severely stress German-Polish relations later on, which had been uncomplicated until then.

Situation in the 19th century

After the Napoleonic Wars, Prussia obtained the Grand Duchy of Posen and Austria remained in possession of Galicia. In May 1815 king Frederick William III. issued a manifest to the Poles in Posen:

You also have a Fatherland. [...] You will be incorporated into my monarchy without having to renounce your nationality. [...] You will receive a constitution like the other provinces of my kingdom. Your religion will be upheld. [...] Your language shall be used like the German language in all public affairs and everyone of you with suitable capabilities shall get the opportunity to get an appointment to a public office. [...]

The minister for Education Altenstein stated in 1823:[3]

Concerning the spread of the German language it is most important to get a clear understanding of the aims, whether it should be the aim to promote the understanding of German among Polish-speaking subjects or whether it should be the aim to gradually and slowly Germanise the Poles. According to the judgement of the minister only the first is necessary, advisable and possible, the second is not advisable and not accomplishable. To be good subjects it is desirable for the Poles to understand the language of government. However, it is not necessary for them to give up or postpone their mother language. The possession of two languages shall not be seen as a disadvantage but as a benefit instead because it is usually associated with a higher flexibility of the mind. [..] Religion and language are the highest sanctuaries of a nation and all attitudes and perceptions are founded on them. A government that [...] is indifferent or even hostile against them creates bitterness, debases the nation and generates disloyal subjects.

In the first half of the 19th century, Prussian language policy remained largely tolerant. However, this tolerance gradually changed in the second half of the 19th century after the foundation of the German Emprire in 1871. Successive policies aimed at the elimination of non-German languages from public life and from academic settings, such as schools. Later in the German Empire, Poles were (together with Danes, Alsatians, German Catholics and Socialists) portrayed as "Reichsfeinde" ("foes to the empire").[4] In addition, in 1885, the Prussian Settlement Commission financed from the national government's budget was set up to buy land from non-German hands and distribute it among German farmers.[5] [citation needed] From 1908 the committee was entitled to force the landowners to sell the land. Other means included the Prussian deportations from 1885–1890, in which non-Prussian nationals who had lived in Prussia for substantial time periods (mostly Poles and Jews) were removed and a ban was issued on the building of houses by non-Germans (see Drzymała's van). Germanisation policy in schools also took the form of abuse of Polish children by Prussian officials (see Września). Germanisation unintentionally stimulated resistance, usually in the form of home schooling and tighter unity in the minority groups.

In 1910, Maria Konopnicka responded to the increasing persecution of Polish people by Germans by writing her famous song called Rota that instantly became a national symbol for Poles, with its sentence known to many Poles: The German will not spit in our face, nor will he Germanise our children.[citation needed] Thus, the German efforts to eradicate Polish culture, language, and people met not only with failure, but managed to reinforce the Polish national identity and strengthened efforts of Poles to re-establish a Polish state.[6]

An international meeting of socialists held in Brussels in 1902 condemned the Germanisation of Poles in Prussia, calling it "barbarous".[7]

Prussian Lithuanians

Prussian Lithuanians living in East Prussia experienced similar policies of Germanisation. Although ethnic Lithuanians had constituted a majority in areas of East Prussia during the 15th and 16th centuries (from the early 16th century it was often referred to as Lithuania Minor), the Lithuanian population began to shrink in the 18th century. Plague and subsequent immigration from Germany, notably from Salzburg, were the primary factors in this development. Germanisation policies were tightened during the 19th century, but even into the early 20th century the territories north and south/south-west of the Neman River contained a Lithuanian majority. Kursenieki experienced similar developments, but this ethnic group never had a large population.

Polish Coal Miners in the Ruhr Valley

Another form of Germanisation was the relation between the German state and Polish coal miners in the Ruhr area. Due to migration within the German Empire, as many as 350,000 Polish nationals made their way to the Ruhr in the late 19th century, where they worked in the coal and iron industries. German authorities viewed them as potential danger and a threat and as a "suspected political and national" element. All Polish workers had special cards and were under constant observation by German authorities. In addition, anti-Polish stereotypes were promoted, such as postcards with jokes about Poles, presenting them as irresponsible people, similar to the treatment of the Irish in New England around the same time. Many Polish traditional and religious songs were forbidden by Prussian authorities.[citation needed] Their citizens' rights were also limited by German state.[8]

Polish response

In response to these policies, the Polish formed their own organisations to maintain their interests and ethnic identity. The Sokol sports clubs and the workers' union Zjednoczenie Zawodowe Polskie (ZZP), Wiarus Polski (press), and Bank Robotnikow were among the best-known such organisations near the Ruhr. At first the Polish workers, ostracised by their German counterparts, had supported the Catholic centre party.[9] Since the beginning of the 20th century their support more and more shifted towards the social democrats.[10] In 1905, Polish and German workers organised their first common strike.[10] Under the Namensänderungsgesetz[10] (law of changing surnames), a significant number of "Ruhr-Poles" change their surnames and Christian names to "Germanised" forms, in order to evade ethnic discrimination. As the Prussian authorities during the Kulturkampf suppressed Catholic services in Polish language by Polish priests, the Poles had to rely on German Catholic priests. Increasing intermarriage between Germans and Poles contributed much to the Germanisation of ethnic Poles in the Ruhr area.

During the Weimar Republic, Poles first were recognised as minority only in Upper Silesia. The peace treaties after the First World War did contain an obligation for Poland to protect its national minorities (Germans, Ukrainians and other), whereas no such clause was introduced by the victors in the Treaty of Versailles with Germany. In 1928, the "Minderheitenschulgesetz" (minorities school act) regulated education of minority children in their native tongue.[11] From 1930 on Poland and Germany agreed to treat their minorities fairly.[12]

Germanisation under the Third Reich

During the Nazi period, the lives of certain minorities in Germany were threatened. Germanisation by Nazi Germany was referred to as "Aryanisation".

Eastern Germanisation

Plans

The East was intended as the Lebensraum that the Nazis were seeking, to be filled with Germans. Hitler, speaking with generals immediately prior to his chancellorship, declared that people could not be Germanised; only the soil could be.[13] When the program was in progress, Heinrich Himmler explicitly warned against equating this new Germanisation with that which had occurred earlier:

It is not our task to Germanise the East in the old sense, that is, to teach the people there the German language and German law, but to see to it that only people of purely German, Germanic blood live in the East. (Himmler)

It should be noted that the policy of Germanisation in the Nazi period carried an explicitly ethno-racial rather than purely nationalist meaning by virtue of culture or linguistics, aiming for the spread of a "biologically superior" Aryan race rather than that of the German nation. Therefore, this did not mean a total extermination of all people there, as Eastern Europe was regarded as having people of Aryan/Nordic descent, particularly among their leaders.[14] Indeed Himmler also declared that no drop of German blood would be lost or left behind for an alien race.[15] In Nazi documents, even reading the term "German" can be problematic, since it could be used to refer to people classifed as "ethnic Germans" who spoke no German.[16]

Inside Germany, propaganda, such the film Heimkehr, depicted these ethnic Germans as deeply persecuted—often with recognisable Nazi tactics—and the invasion and Germanisation as necessary to protect them.[17] Forced labor of ethnic Germans and persecution of them were major themes of the anti-Polish propaganda campaign of 1939, prior to the invasion.[18] Bloody Sunday was widely exploited as depicting the Poles as murderous toward Germans.[19]

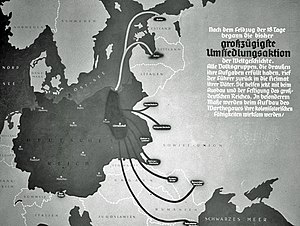

In a top-secret memorandum, "The Treatment of Racial Aliens in the East", dated May 25, 1940, Himmler wrote "We need to divide Poland's many different ethnic groups up into as many parts and splinter groups as possible".[20][21] There were two Germanisation actions in occupied Poland realised in this way:

- The grouping of Polish Gorals ("Highlanders") into the hypothetical Goralenvolk, a project which was ultimately abandoned due to lack of support among the Goral population;

- The assignment of Pomerelian Kashubians onto the Deutsche Volksliste, as they were considered capable of assimilation into the German population (several high-ranking Nazis deemed them to be descended from ancient Gothic peoples).[22]

Selection and Expulsion

Germanisation began with the classification of people suitable as defined on the Nazi Volksliste, and treated according to their categorisation.[15] The Germans regarded the holding of active leadership roles as an Aryan trait, whereas a tendency to avoid leadership and a perceived fatalism was associated by many Germans with Slavonic peoples.[23] Adults who were selected for but resisted Germanisation were executed. Such execution was carried out on the grounds that German blood should not support non-German nations,[21] and that killing them would deprive foreign nations of superior leaders.[14] The Intelligenzaktion was justified, even though these elites were regarded as likely of German blood, because such blood enabled them to provide leadership for the fatalistic Slavs.[23] Germanizing "racially valuable" elements would prevent any increase in the Polish intelligenstia,[21] as the dynamic leadership would have to come from German blood.[24]

Under Generalplan Ost, a percentage of Slavs in the conquered territories were to be Germanised. Gauleiters Albert Forster and Arthur Greiser reported to Hitler that 10 percent of the Polish population contained "Germanic blood", and were thus suitable for Germanisation.[25] The Reichskommissars in northern and central Russia reported similar figures.[25] Those unfit for Germanisation were to be expelled from the areas marked out for German settlement. In considering the fate of the individual nations, the architects of the Plan decided that it would be possible to Germanise about 50 percent of the Czechs, 35 percent of the Ukrainians and 25 percent of the Belorussians. The remainder would be deported to western Siberia and other regions. In 1941 it was decided that the Polish nation should be completely destroyed; the German leadership decided that in ten to 20 years, the Polish state under German occupation was to be fully cleared of any ethnic Poles and resettled by German colonists.[26]

In the Baltic States, after an agreement with Stalin, who suspected they would be loyal to the Nazis,[27] the Nazis set out to encourage the departure of "ethnic Germans" by the use of propaganda. This included using scare tactics about the Soviet Union, and led to tens of thousands leaving.[28] Those who left were not referred to as "refugees", but were rather described as "answering the call of the Fuhrer."[29] German propaganda films such as GPU[30] and Friesennot[31] depicted the Baltic Germans as deeply persecuted in their native lands. Packed into camps for racial evaluation, they were divided into groups: A, Altreich, who were to be settled in Germany and allowed neither farms nor business (to allow for closer watch), S Sonderfall, who were used as forced labor, and O Ost-Falle, the best classification, to be settled in the Eastern Wall—the occupied regions, to protect German from the East—and allowed independence.[32] This last group was often given Polish homes where the families had been evicted so quickly that half-eaten meals were on tables and small children had clearly been taken from unmade beds.[33] Members of Hitler Youth and the League of German Girls were assigned the task of overseeing such evictions to ensure that the Poles left behind most of their belongings for the use of the settlers.[34] The deportation orders required that enough Poles be removed to provide for every settler — that, for instance, if twenty German "master bakers" were sent, twenty Polish bakeries had to have their owners removed.[35]

Settlement and Germanisation

This colonisation incorporated 350,000 such Baltic Germans and 1.7 million Poles deemed Germanisable, including between one and two hundred thousand children who had been taken from their parents (plus about 400,000 German settlers from the "Old Reich").[36] Nazi authorities had great fears of these settlers being tainted by their Polish neighbors and not only warned them to let their "foreign and alien" surroundings to have no impact on their Germanness, but settled them in compact communities, which could be easily monitored by the police.[37] Only families classified as "highly valuable" were kept together.[38]

For Poles who did not resist and the resettled ethnic Germans, Germanisation began. Militant party members were sent to teach them to be "true Germans".[39] Hitler Youth and League of German Girls sent young people for "Eastern Service", which entailed (particularly for the girls) assisting in Germanisation efforts.[40] One member of the League recounted afterward that she at first pitied the starving Polish children, but soon realised this was "politically naive" and to concentrate solely on the Volksdeutsche; her beliefs in the stupidity of Poles were reinforced by the lack of educated Poles, not knowing they had been jailed or deported.[41] This included instruction in the German language, as many spoke only Polish or Russian.[42] They found the new settlers dispirited and put on various entertainments such as songfests to encourage them and ease their transition.[43] Membership in Hitler Youth and the League of German Girls was enforced for the children.[34] Goebbels and other propagandists worked to establish cultural centers and other means to created Volkstum or racial consciousness in the settlers.[44] This was needed to perpetuate their work; only by effective Germanisation could mothers, in particular, create the German home.[45] Goebbels also was the official patron of Deutsches Ordensland or Land of Germanic Order, an organisation to promote Germanisation.[46] This efforts were used in propaganda in Germany itself, as when NS-Frauen-Warte's cover article was on "Germany is building in the East."[47]

Germanisation tended to proceed slowly. Peasants given larger farms and more animals than they had had in the Baltic States could not cope.[48] Younger people spoke German poorly, if at all, and older people were found to become completely denationalised, requiring that they be Germanised in Germany before they could be restored to the East where they would increase the German population.[23] Many resettled Baltic Germans learned Polish quickly and got along better with the locals than with the German authorities.[40] After two years of efforts, the authorities concluded that true Germanisation would have to await the end of the war.[37]

Other efforts in Poland were also regarded as Germanisation, as for instance the setting up of the IG-Farben at Auschwitz-Monowitz.[49]

Germanisation Outside Poland

Later, Ukraine was also targeted for Germanisation. Thirty special SS squads took over villages where ethnic Germans predominated, and expelled or shot any Jews or Slavs living in them, in a policy of concentration.[50] The colony Hegewald was set up in the Ukraine as well.[51] Ukrainians were forcibly deported, and ethnic Germans forcibly relocated there.[52] Racial assignment was carried out in a confused manner; the Reich rule was three German grandparents, but some asserted that any person who acted like a German and evinced no "racial concerns" should be eligible.[53]

As the need for workers in Germany grew, the standards for who qualified as Germanisable were lowered.[54] Himmler's declaration that "it is in the nature of German blood to resist" led to the paradoxical conclusion that Balts or Poles who resisted Germanisation measures were regarded as more suitable material than more compliant ones.[54]

Plans to eliminate Slavs from Soviet territory to allow German settlement included starvation; Nazi leaders expected that millions would die after they removed such supplies as they needed.[52] This was regarded as an actual advantage by Nazi officials.[54] When Hitler received a report of many, well-fed Ukrainian children, he declared the promotion of contraception and abortion was urgently needed, and neither medical care nor education was to be provided.[55] Experiments in mass sterilisation in concentration camps may also have been intended for use on the Slavonic populations.[56]

Eastern Workers

When young women from the East were recruited to work as nannies in Germany, they were required to be suitable for Germanisation, both because they would work with German children, and because they might be sexually exploited.[57] The program was praised for not only allowing more women to have children with their new domestic servants to assist in their labours, but for reclaiming the German blood and giving advantages to the women, who would work in Germany, and might marry there.[58]

Children

"Racially acceptable" children were taken from their families in order to be brought up as Germans.[59]

Children were selected for "racially valuable traits" before being shipped to Germany.[21] Many Nazis were astounded at the number of Polish children found to exhibit "Nordic" traits, but assumed that all such children were genuinely German children, who had been Polonised; Hans Frank summoned up such views when he declared, "When we see a blue-eyed child we are surprised that she is speaking Polish."[23] The term used for them was wiedereindeutschungsfähig -- meaning capable of being re-Germanised.[60] These might include the children of people executed for resisting Germanisation.[14] If attempts to Germanise them failed, or they were determined to be unfit, they would be killed to eliminate their value to the opponents of the Reich.[21]

In German-occupied Poland, it is estimated that a number ranging from 50,000 to 200,000 children were removed from their families to be Germanised.[61] The Kinder KZ was founded specifically to hold such children. It is estimated that at least 10,000 of them were murdered in the process as they were determined unfit and sent to concentration camps and faced brutal treatment or perished in the harsh conditions during their transport in cattle wagons, and only 10-15% returned to their families after the war.[62] Obligatory Hitlerjugend membership made dialogue between old and young next to impossible, as use of languages other than German was discouraged by officials. Members of minority organisations were either sent to concentration camps by German authorities or executed.

Many children, particularly Polish and Yugoslavian who were among the first taken, declared on being found by Allied forces that they were German.[63] Russian and Ukrainian children, while not gotten to this stage, still had been taught to hate their native countries and did not want to return.[63]

Western Germanisation

In contemporary German usage the process of Germanisation was referred to as Germanisierung (Germanicisation, i.e. to make something Germanic) rather than Eindeutschung (Germanisation, i.e. to make something German). According to Nazi racial theories, the Germanic peoples of Europe such as the Scandinavians, the Dutch, and the Flemish, were like the Germans themselves a part of the Aryan Master Race, regardless of these peoples' own acknowledgement of their "Aryan" identity.

Germanisation in these conquered countries proceeded more slowly. The Nazis had a need for local cooperation and the local industry with its workers; furthermore, the countries were regarded as more racially acceptable, the assortment of racial categories being boiled down by the average German to mean "East is bad and West is acceptable."[64] The plan was to win the Germanic elements over slowly, through education.[65] Himmler, after a secret tour of Belgium and Holland, happily declared the people would be a racial benefit to Germany.[65] Occupying troops were kept under strict discipline and instructed to be friendly to win the population over, a technique that did not work not only because of their having conquered the countries, but because it was soon clear that being German was far superior to being merely Nordic.[66] Pamphlets, for instance, enjoined all German women to avoid sexual intercourse with all foreign workers brought to Germany as a danger to their blood.[67]

Various Germanisation plans were implemented. Dutch and Belgian Flemish prisoners of war were sent home quickly, to increase Germanic population, while Belgian French ones were kept as laborers.[66] Lebensborn homes were set up in Norway for Norwegian women impregnanted by German soldiers, with adoption by Norwegian parents being forbidden for any child born there.[68] Alsace-Lorraine was annexed; thousands of residents, too loyal to France, Jewish, or North Africa, were deported to Vichy France; French was forbidden in schools; intransigent German speakers were shipped back to Germany for re-Germanisation, just as Poles were.[69] Extensive racial classification was practiced in France, for future uses.[70]

Himmler's original plan for the colony of Hegewald was to recruit settlers from Scandanvia and the Netherlands; this was unsuccessful.[71]

Himmler's masseuse, Felix Kersten, claimed an even more radical scheme was devised by Himmler which envisioned the near-future resettlement of the entire Dutch nation to agricultural lands in the Vistula and Bug valleys of German-occupied Poland in order to facilitate their immediate Germanisation.[72] 8.5 million people were to be relocated in total, after which all Dutch capital and real estate would be confiscated by the Reich and distributed to reliable SS men, and an SS Province of Holland declared in vacated Dutch territory. However this claim was shown to be a myth by Loe de Jong in his book Two Legends of the Third Reich.[73]

After World War II

In post-1945 Germany and post-1945 Austria, the concept of Germanisation is no longer considered relevant. Danes, Frisians, and Slavic Sorbs are classified as traditional ethnic minorities and are guaranteed cultural autonomy by both the federal and state governments. Concerning the Danes, there is a treaty between Denmark and Germany from 1955 regulating the status of the German minority in Denmark and vice versa. Concerning the Frisians, the northern federal-state of Schleswig-Holstein passed a special law aimed at preserving the language.[74] The cultural autonomy of the Sorbs is a matter of the constitutions of both Saxony and Brandenburg. Nevertheless, almost all of the Sorbs are bilingual and the Lower Sorbian language is regarded as endangered, as the number of native speakers is dwindling, even though there are programmes funded by the state to sustain the language.

In post-1945 Austria, in the federal-state of Burgenland, Hungarian and Croatian have regional protection by law. In Carinthia, Slovenian-speaking Austrians are also protected by the law.

Descendants of Polish migrant workers and miners have intermarried with the local population and are culturally German or of mixed culture. It is different with modern and present-day immigration from Poland to Germany after the fall of the iron curtain. These immigrants usually are Polish citizens and live as foreigners in Germany. For many immigrant Poles, Polish ethnicity is not the prime category through which they wish to characterise themselves or want to be evaluated by others,[75] as it could impact their lives in a negative way.

Linguistic Germanisation

In linguistics, Germanisation usually means the change in spelling of loanwords to the rules of the German language — for example the change from the imported word bureau to Büro.

Surname and Genetic Evidence of Historic Germanisation of Slavs

Immel, Uta-Dorothee et al. (2006) found a profound stratification observed among East-German male lineages and their correlation with surnames. The best documented wave of migration was that of Eastern Germanic tribes and Slavs, driven by the Huns, that led to the downfall of the Roman Empire. In historic times, two major instances of assimilation of Slavic people into the German nation occurred. Around 950 AD, the Eastern Franks(Ottonian dynasty) started to put pressure upon the Slavic peoples inhabiting large areas of what was to become, in the mid of the 20th Century, the German Democratic Republic. By 1100 AD, after more than 100 years of wars and proselytisation, the complete area of contemporary Germany had come under the influence of the German Empire. During the following centuries, most of the non-Germanic tribes (like the Baltic Prussians) completely abandoned their language, and their descendants are today regarded as 'typically German'. Only in a small area, southeast of Berlin, known as the Lausitz, the Slavic-speaking Sorb people maintained their language and culture, and their descendants today represent the only recognised, non-immigrant minority in East Germany. This is mentioned in more details in the sections above. In any case, the names of many cities, including Berlin (meaning 'little swamp'), and some surnames, most notably those of 'typically Prussian' nature like 'von Clausewitz' or 'Virchow', still reflect the Slavic roots of this part of Germany. The second major assimilation of people with Slavic ancestry occurred during the Industrial Revolution in the 19th Century. Thousands of people from Eastern Europe migrated to the West to work in the surging industrial areas of Germany (Silesia, Ruhr-Area). Although they brought their surnames with them, they nevertheless became culturally amalgamated quite rapidly by the German majority.[76]

The Halle region is located exactly at the intersection of the Germanic and Slavic spheres of influence of the 10th century, but it is also a traditional mining and chemical industry area (Halle-Leipzig-Bitterfeld) that has attracted Slavic workers during the Industrial Revolution. Both of these factors should have had an impact upon the male-specific genetic structure of the local population where surnames of Germanic and Slavic origin are about equally frequent. In terms of the relative importance of the two historic instances for the observed correlation between Y-STR haplotypes and surname characteristics, it is interesting to note that surnames first occurred in Europe in Venice during the 9th Century. From there, the law of name bearing was adopted in France and Catalonia in the 11th, and in England, and Western and Southern Germany in the 12th Century. In the North and East of Germany, the custom was practised no earlier than the 15th Century and, in some rural regions, surnames became fashionable only in the 18th century, nearly 900 years after their first appearance in Europe. Furthermore, surnames frequently changed or became modified until the beginning of the 19th century. Therefore, it appears unlikely that the correlation between surnames and Y-STR haplotypes observed in our study dates back to the Middle Ages, but is more likely to be the result of the immigration of industrial workers in the 19th Century instead. In this respect, Central Europe appears to differ from England and Ireland where patrilineally inherited names are presumed to have a much deeper rooting.[76]

"The Halle samples were divided into three subgroups, according to surname. Two larger groups comprised 195 males with surnames that were definitely German ('G') and 185 males with definitely Slavic surnames ('S'). The third group contained 39 males with mixed German-Slavic surnames ('M'). Samples of 29 Sorbs and some 1313 published haplotypes from Polish males 13 were used for comparison. Surname groups were defined on the basis of spelling, using certain combinations of consonants and surname suffixes to categorise the origin of the name in question. Suffixes '-er', '-mann' and '-burg', for example, are typically German whereas '-ke', '-ka', '-ow' and '-ski' are typically Slavic. In addition, the root morphemes of surnames were also examined. Examples for a Slavic root comprise 'Lessing', which sounds German but was derived from the Slavic expression for "forest settler", and "Kafka", which in Czech means "jackdaw". Mixed surnames include both German and Slavic elements, that is, a German basis and a Slavic ending, or vice versa (Wudtke or Kuppke). These surnames are the result of a long parallel usage of both German and Slavic languages in the eastern part of Germany."[76]

A similar characterisation of the present samples in terms of the relative proportion of the fringe haplotypes resulted in highly significant differences between the two surname-defined German subgroups, G+M and S (chi2=13.094, 2 df, P=0.001). While 88 of the 234 haplotypes (38%) in the combined G+M group were classified as 'Western', this was the case for only 42 of the 185 haplotypes (23%) in group S. In contrast, 80 G+M haplotypes (34%) were of 'Eastern' type compared to 91 S haplotypes (49%). The portion of unclassifiable haplotypes was 28% in both groups (66 in G+M, 52 in S).[76]

Professor Jürgen Udolph, of the University of Leipzig Institute for Slavic Studies, contends that 15 million people in modern Germany have Slavic or specifically Polish surnames.[77] He believes the concentration of Slavic names in East Germany is even higher than the national average, accounting for 30% of all surnames in the region.[78][79]

See also

References

- ^ Polabian language

- ^ a b c d e f "A Country Study: Hungary – Hungary under the Habsburgs". Federal Research Division. Library of Congress. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ^ cited in: Richard Cromer: Die Sprachenrechte der Polen in Preußen in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts. Journal Nation und Staat, Vol 6, 1932/33, p. 614, also cited in: Martin Broszat Zweihundert Jahre deutsche Polenpolitik (Two-hundred years or German Poles politics). Suhrkamp 1972, p. 90, ISBN. 3-518-36574-6. During the discussions in the Reichstag in January 1875, Altenstein's statement was cited by the opponents of Bismarck's politics.

- ^ Bismarck and the German Empire, 1871–1918

- ^ "Die Germanisirung der polnisch-preußischen Landestheile." In "Neueste Mittheilungen, V.Jahrgang, No. 17, 11th February, 1886. Berlin: Dr. H. Klee.http://amtspresse.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/vollanzeige.php?file=11614109%2F1886%2F1886-02-11.xml&s=1

- ^ Kossert, Andreas."Grenzlandpolitik und Ostforschung an der Grenze des Reiches: Das ostpreußische Masuren." In "Viertelsjahrheft für Zeitgeschichte." Oldenbourg: Institut für Zeitgeschichte München-Berlin, April 2003. Pp. 121–123. http://www.kossert.net/dateien/vfzg5122003.pdf

- ^ http://www.echoed.com.au/chronicle/1902/jan-feb/world.htm

- ^ Migration Past, Migration Future: Germany and the United States

- ^ http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zentrumspartei

- ^ a b c 1880, Polen im Ruhrgebiet

- ^ "Polen im Ruhrgebiet 1870–1945" — Deutsch-polnische Tagung - H-Soz-u-Kult / Tagungsberichte

- ^ Johann Ziesch

- ^ Richard Bessel, Nazism and War, p 36 ISBN 0-679-64094-0

- ^ a b c HITLER'S PLANS FOR EASTERN EUROPE

- ^ a b Richard Overy, The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia, p543 ISBN 0-393-02030-4

- ^ Pierre Aycoberry, The Social History of the Third Reich, 1933-1945, p 2, ISBN 1-56584-549-8

- ^ Erwin Leiser, Nazi Cinema p69-71 ISBN 0-02-570230-0

- ^ Robert Edwin Hertzstein, The War That Hitler Won p173 ISBN 399-11845-4

- ^ Robert Edwin Hertzstein, The War That Hitler Won p289 ISBN 399-11845-4

- ^ Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 1957, No. 2

- ^ a b c d e Nazi Conspiracy & Aggression Volume I Chapter XIII Germanization & Spoliation

- ^ Diemut Majer, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, "Non-Germans" Under the Third Reich: The Nazi Judicial and Administrative System in Germany and Occupied Eastern Europe with Special Regard to Occupied Poland, 1939–1945 Von Diemut Majer, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, JHU Press, 2003, p.240, ISBN 0801864933.

- ^ a b c d Lukas, Richard C. Did the Children Cry?

- ^ Richard C. Lukas, Forgotten Holocaust p24 ISBN 0-7818-0528-7

- ^ a b Speer, Albert (1976). Spandau: The Secret Diaries, p. 49. Macmillan Company.

- ^ Volker R. Berghahn "Germans and Poles 1871–1945" in "Germany and Eastern Europe: Cultural Identities and Cultural Differences", Rodopi 1999

- ^ Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web p. 204 ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ^ Nicholas, p. 207-9

- ^ Nicholas, p. 206

- ^ Erwin Leiser, Nazi Cinema p44-5 ISBN 0-02-570230-0

- ^ Erwin Leiser, Nazi Cinema p39-40 ISBN 0-02-570230-0

- ^ Nicholas, p. 213

- ^ Nicholas, p. 213-4

- ^ a b Walter S. Zapotoczny , "Rulers of the World: The Hitler Youth"

- ^ Michael Sontheimer, "When We Finish, Nobody Is Left Alive" 05/27/2011 Spiegel

- ^ Pierre Aycoberry, The Social History of the Third Reich, 1933-1945, p 228, ISBN 1-56584-549-8

- ^ a b Richard C. Lukas, Forgotten Holocaust p20 ISBN 0-7818-0528-7

- ^ Pierre Aycoberry, The Social History of the Third Reich, 1933–1945, p 229, ISBN 1-56584-549-8

- ^ Pierre Aycoberry, The Social History of the Third Reich, 1933–1945, p 255, ISBN 1-56584-549-8

- ^ a b Nicholas, p. 215

- ^ Nicholas, p 217

- ^ Nicholas, p. 217

- ^ Nicholas, p. 218

- ^ Robert Edwin Hertzstein, The War That Hitler Won p137 ISBN 399-11845-4

- ^ Leila J. Rupp, Mobilizing Women for War, p 122, ISBN 05109-7

- ^ Robert Edwin Hertzstein, The War That Hitler Won p139 ISBN 399-11845-4

- ^ "The Frauen Warte: 1935–1945"

- ^ Richard C. Lukas, Forgotten Holocaust p19-20 ISBN 0-7818-0528-7

- ^ Pierre Aycoberry, The Social History of the Third Reich, 1933-1945, p 265, ISBN 1-56584-549-8

- ^ Karel C. Berkhoff, Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule p44 ISBN 0-674-01313-1

- ^ Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web p336, ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ^ a b Karel C. Berkhoff, Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule p45 ISBN 0-674-01313-1

- ^ Karel C. Berkhoff, Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule p211 ISBN 0-674-01313-1

- ^ a b c Robert Cecil, The Myth of the Master Race: Alfred Rosenberg and Nazi Ideology p199 ISBN 0-396-06577-5

- ^ Robert Cecil, The Myth of the Master Race: Alfred Rosenberg and Nazi Ideology p207 ISBN 0-396-06577-5

- ^ Gerhard L. Weinberg, Visions of Victory: The Hopes of Eight World War II Leaders p 24 ISBN 0-521-85254-4

- ^ Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Chilren of Europe in the Nazi Web p255, ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ^ Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Chilren of Europe in the Nazi Web p256, ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ^ Lebensraum, Aryanization, Germanization and Judenrein, Judenfrei: concepts in the holocaust or shoah

- ^ Milton, Sybil. "Non-Jewish Children in the Camps". Museum of Tolerance, Multimedia Learning Center Online. Annual 5, Chapter 2. Copyright © 1997, The Simon Wiesenthal Center.

- ^ Hitler's War; Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe

- ^ Dzieciñstwo zabra³a wojna > Newsroom - Roztocze Online - informacje regionalne - Zamo¶æ, Bi³goraj, Hrubieszów, Lubaczów,Tomaszów Lubelski, Lubaczów - Roztocze OnLine

- ^ a b Nicholas, p 479

- ^ Lynn H. Nicholas, p. 263

- ^ a b Nicholas, p. 273

- ^ a b Nicholas, p. 274 ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ^ Leila J. Rupp, Mobilizing Women for War, p 124–5, ISBN 05109-7

- ^ Nicholas, p. 275-6

- ^ Nicholas, p. 277

- ^ Nicholas, p. 278

- ^ Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web p330-1, ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ^ Waller, John H. (2002). The devil's doctor: Felix Kersten and the secret plot to turn Himmler against Hitler. Wiley, p. 20 [1]

- ^ Louis de Jong, 1972, reprinted in German translation: H-H. Wilhelm and L. de Jong. Zwei Legenden aus dem dritten Reich : quellenkritische Studien, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt 1974, pp 79–142.

- ^ http://de.wikisource.org/wiki/Friesisch-Gesetz

- ^ Polonia in Germany

- ^ a b c d Immel, Uta-Dorothee et al. "Y-chromosomal STR haplotype analysis reveals surname-associated strata in the East-German population". European Journal of Human Genetics. pg. 1-6, Copyright © 2006, The Nature Publishing Group.

- ^ Stumpf, Rainer. "Auf der Suche nach dem Ich". Magazin Deutschland Online, 2009.

- ^ Unknown. "Der NDR 1 Niedersachsen Namenforscher". Der NDR, 2011.

- ^ Unknown. "Namensforschung: Herr Angermann wohnt am Anger". Frantfurter Allemeine Online, 2011.

External links

- Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes from May 2008

- Cultural assimilation

- German language

- Germany–Poland relations

- Historical linguistics

- History of Europe

- History of Germany

- History of Poland (1569–1795)

- History of Poland (1795–1918)

- History of Poland (1939–1945)

- History of the Lithuanian language

- Human rights abuses

- Transliteration

- Types of words