Attempted assassination of Harry S. Truman

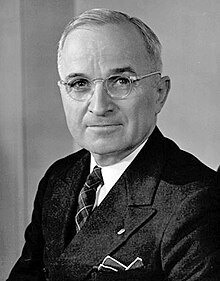

Harry S. Truman | |

|---|---|

| |

| 33rd President of the United States Assassination attempt on November 1, 1950 | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

|---|

|

The second of two assassination attempts on U.S. President Harry S. Truman occurred on November 1, 1950. [1] It was carried out by two Puerto Rican pro-independence activists, Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola, while the President resided at the Blair House. It resulted in the death of Torresola and White House Police officer Leslie Coffelt. President Harry S. Truman was not harmed.[2]

Prelude to the assassination attempt

In the 1940s, Puerto Rican Nationalists were increasingly angered by what they viewed as great injustices towards Puerto Rico. These included the injection of live cancer cells into Puerto Rican patients by Dr. Cornelius P. Rhoads,[3] the Ponce Massacre,[4] the shooting of Vidal Santiago Díaz by forty U.S.-trained policemen,[5][6] the extrajudicial murders of numerous Nationalists,[7][8] the jailing of Pedro Albizu Campos for his advocacy of armed resistance,[9] and the impending change of Puerto Rico's status to a self-governing "Estado Libre Associado" with conditions set by the US.[10]

The Popular Democratic Party of Puerto Rico (PPD) fostered the idea of the creation of a "new" political status. In accordance with PPD ideals, the U.S. Government allowed the people of Puerto Rico to elect their own governor. In exchange the United States would continue to control the island's monetary system, defense, custom duties and would not permit the island to enter into treaties with foreign nations.[10]

The laws of Puerto Rico were also subject to the approval of the Federal government of the United States.[10] This political status, called an Estado Libre Associado, was considered a colonial farce by advocates of Puerto Rican independence.[11]

Law 53 (The Puerto Rican Gag Law)

In 1948, a bill was introduced before the Puerto Rican Senate which would restrain the rights of the independence and Nationalist movements in the island. The Senate at the time was controlled by the PPD and presided by Luis Muñoz Marín.[12]

The bill, known as Law 53 and the Ley de la Mordaza (Gag Law), passed the legislature on May 21, 1948 and was signed into law on June 10, 1948, by the U.S.-appointed governor of Puerto Rico Jesús T. Piñero. It closely resembled the anti-communist Smith Law passed in the United States - and it created as much chaos on the island, as Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee did, on the mainland U.S.[13]

Under this law it became a crime to own or display a Puerto Rican flag anywhere, even in one's own home. It also became a crime to speak against the U.S. government; to speak in favor of Puerto Rican independence; to print, publish, sell or exhibit any material intended to paralyze or destroy the insular government; or to organize any society, group or assembly of people with a similar destructive intent.

Anyone accused and found guilty of disobeying the law could be sentenced to ten years imprisonment, a fine of $10,000 dollars (US), or both.

According to Dr. Leopoldo Figueroa, member of the Partido Estadista Puertorriqueño (Puerto Rican Statehood Party) and the only member of the Puerto Rico House of Representatives who did not belong to the PPD, the law was repressive and in direct violation of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees Freedom of Speech.[14]

Figueroa pointed out that every living Puerto Rican had been "granted" irrevocable U.S. citizenship, so that they could fight in World War I and other American armed conflicts. As such, from 1917 onward, every Puerto Rican was born with full citizenship, and full U.S. constitutional protections. Therefore Law 53 was unconstitutional, since it violated the First Amendment rights of every Puerto Rican.[15]

The Nationalist Uprising

As a direct and immediate consequence of Law 53, hundreds of sympathizers with the independence movement were imprisoned. This included members of the Nationalist Party who opposed Luis Muñoz Marín, his party, and his political ambition to become Governor.[16] Marín won the elections of November 2, 1948, and was sworn in as Puerto Rico's first elected governor on January 2, 1949.[16]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

From 1949 to 1950, the Nationalists in the island began to plan and prepare an armed revolution. The revolution was to take place in 1952, on the date the United States Congress was to approve the creation of the political status Free Associated State (Estado Libre Associado) for Puerto Rico.

Albizu Campos called for an armed revolution because he considered the "new political status" a colonial farce. Campos picked the town of Jayuya as the headquarters of the revolution because of its location, and weapons were stored in the home of Blanca Canales.

On October 26, 1950, Albizu Campos was holding a meeting in Fajardo when he received word that his house in San Juan was surrounded by police waiting to arrest him. He was also told that the police had already arrested other Nationalist leaders. He escaped from Fajardo and ordered the revolution to start. On October 27, the police in the town of Peñuelas, intercepted and fired upon a caravan of Nationalists, killing four.[17] On October 30, the Nationalists staged uprisings in the towns of Ponce, Mayagüez, Naranjito, Arecibo, Utuado (Utuado Uprising), San Juan (San Juan Nationalist revolt), and Jayuya.

The first incident of the Nationalist uprisings occurred in the pre-dawn hours of October 29. The Insular Police of that town surrounded the house of the mother of Melitón Muñiz Santos, the president of the Peñuelas Nationalist Party in the barrio Macaná, under the pretext that he was storing weapons for the Nationalist Revolt. Without warning, the police fired on the house and a gunfight between factions ensued. Two Nationalists were killed and six police officers were wounded.[18] Nationalists Meliton Muñoz Santos, Roberto Jaume Rodriguez, Estanislao Lugo Santiago, Marcelino Turell, William Gutirrez and Marcelino Berrios were arrested and accused of participating in an ambush against the local Insular Police.[19][20]

In Jayuya, Canales and the Torresolas led the armed Nationalists into the town and attacked the police station. Shots were fired, one officer was killed, three were wounded, the others dropped their weapons and surrendered. The Nationalists cut the telephone lines and burned the post office. Canales then led the group into the town square, where the light blue version of the Puerto Rican Flag was raised (it was against U.S.-imposed law to carry a Puerto Rican Flag from 1948 to 1957).[21][22] In the town square, Canales gave a speech and declared Puerto Rico a free Republic.

The U.S. begged to differ. They declared martial law and attacked the town with U.S. bomber planes, land-based artillery, mortar fire, grenades, U.S. infantry troops, and the National Guard.[22] The planes machine-gunned nearly every rooftop in the town. The Nationalists managed to hold the town for three days, then mass arrests followed.

Even though an extensive part of Jayuya was destroyed, news of this military action was prevented from spreading outside of Puerto Rico. It was reported as an "incident between Puerto Ricans" by the American media.[22][23] In response, Nationalists Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola decided to assassinate U.S. President Harry S. Truman. On November 1, 1950, they attacked the Blair House, where Truman was staying in Washington, D.C.

Preparations for the assassination attempt

Griselio Torresola came from a family that believed in the Puerto Rican independence cause, while Oscar Collazo had been participating in the movement since childhood. They met in New York City and became good friends.[24] On October 30, 1950, they received the news that the Jayuya Uprising, led by the nationalist Blanca Canales in Puerto Rico, had failed. Torresola's sister had been wounded and his brother Elio had been arrested.

In view of this, and the mass slaughters which had occurred in Utuado, Jayuya, and other towns throughout Puerto Rico, Collazo and Torresola resolved to assassinate President Truman.[24]

The two men realized that the attempt was near-suicidal, and that they likely would be killed themselves. However, they hoped to bring world attention to the mass slaughters which were occurring in Puerto Rico, and the justness of their dream for Puerto Rican independence. Torresola, as a skilled gunman, taught Collazo how to load and handle a gun. Both men familiarized themselves with the area around the Blair House.[25]

The attempt

At the time of the attempt there were two guard booths out front, which are not present today.

Torresola walked up Pennsylvania Avenue from the west side while his partner, Oscar Collazo, walked up to Capitol police officer Donald Birdzell on the steps of the Blair House. Approaching Birdzell from behind, Collazo pulled out a Walther P38 handgun, pointed it at the officer's back, and pulled the trigger; but since he had failed to chamber a round in it, nothing happened. After pounding on his pistol and fumbling around with it, Collazo managed to chamber and fire the weapon just as Birdzell was turning to face him, striking the officer in his right knee. [24][25]

Nearby, Secret Service Special Agent Floyd Boring and White House Police officer Joseph Davidson heard the shot and opened fire on Collazo with their service revolvers. It was later said that Boring stood back and cocked the hammer on his revolver to make accurate shots, while most of the other officers fired double-action, as quickly as they could.

Collazo returned fire but found himself outgunned, as the wounded Birdzell managed to draw his weapon and join the shootout. Soon after, Collazo was struck by two .38 caliber rounds in the head and right arm, while other officers rushed to join the fight.[24][25][26]

Meanwhile, Torresola approached a guard booth at the west corner of the Blair House, and saw police officer Leslie Coffelt, sitting inside. In a double-handed shooting stance, Torresola quickly pivoted around the opening of the booth.

Since tourists often stopped at his box to ask for information, officer Coffelt was taken by surprise. Torresola fired four shots at him at close range, with a 9 mm German Luger. Three of those shots struck Coffelt in the chest and abdomen, and the fourth went through his policeman's tunic. Coffelt slumped down in his chair, mortally wounded.[24][25]

Torresola then shot police officer Joseph Downs in the hip, before Downs could draw his weapon. Downs turned back toward the house, and was shot twice more by Torresola, in the back and in the neck. Downs staggered to the basement, slumped in, and slammed the door behind him, denying Torresola entry into the Blair House.[24][25]

Torresola then turned his attention to the shoot-out between his partner, Collazo, and several other police officers. He aimed and shot officer Donald Birdzell in the left knee from a distance of approximately 40 feet.

Now shot in both knees, Birdzell was no longer able to stand and was effectively incapacitated (he would later recover). Soon after, the severely wounded Collazo was hit in the chest by a ricochet shot from Davidson, and was also incapacitated.[24][25]

Torresola realized he was out of ammunition. He stood to the immediate left of the Blair House steps while he reloaded. At the same time, President Truman, who had been taking a nap in his second-floor bedroom, awoke to the sound of gunfire outside. President Truman went to his bedroom window, opened it, and looked outside. From where he stood reloading, Torresola was thirty-one feet away from that window.[24][25]

At that same moment, the mortally-wounded Coffelt staggered out of his guard booth, leaned against it, and aimed his revolver at Torresola, who was approximately 30 feet away. Coffelt fired and hit Torresola two inches above the ear, killing him instantly.[27] Coffelt was taken to the hospital and died four hours later.[24][25]

It is unknown whether Torresola saw Truman, when the president opened and looked out his window. If Torresola did see him, then officer Coffelt may have saved Truman's life, and sacrificed his own life in doing so.[28]

The gunfight involving Torresola lasted approximately 20 seconds, while the gunfight with Collazo lasted approximately 38.5 seconds.[29] Only one shot fired by Collazo hit someone, while all of the rest of the damage was done by Torresola.[25]

Aftermath

Coffelt's widow, Cressie E. Coffelt, was asked by President Truman and the Secretary of State to go to Puerto Rico, where she received condolences and expressions of sorrow from various Puerto Rican leaders and crowds. Mrs. Coffelt responded with a speech absolving the island's people of blame for the acts of Collazo and Torresola.

Oscar Collazo was sentenced to death, which was later commuted by Truman to a life sentence. This sentence was commuted by President Jimmy Carter to time served in 1979, and Collazo was released and went back to Puerto Rico. He died in 1994.

Collazo's wife, Rosa, was also arrested by the FBI on suspicion of having conspired with her husband in the attempt, and spent eight months in federal prison. Upon her release from prison, Rosa continued to work with the Nationalist Party. She helped gather 100,000 signatures in an effort to save her husband from the electric chair.[26]

Today, inside the Blair House, a plaque commemorates police officer Leslie Coffelt's sacrifice, heroism, and fidelity to his duty and his country. The day room for the U.S. Secret Service's Uniformed Division at the Blair House is named for Coffelt as well.[26]

See also

- Puerto Rican Nationalist Party Revolts of the 1950s

- United States Capitol shooting incident (1954)

- List of United States presidential assassination attempts

- Jayuya Uprising

- San Juan Nationalist revolt

- Utuado Uprising

- Río Piedras massacre

- Grito de Lares

- Puerto Rican Independence Party

- List of famous Puerto Ricans

References

- ^ "The (First) Attempted Assassination of President Truman"

- ^ Ayoob, Massad (2006). "Drama at Blair House: the attempted assassination of Harry Truman". American Handgunner (March–April 2006). Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- ^ Puerto Ricans Outraged Over Secret Medical Experiments

- ^ 19 Were killed including 2 policemen caught in the cross-fire, The Washington Post Tuesday, December 28, 1999; Page A03. "Apology Isn't Enough for Puerto Rico Spy Victims." Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- ^ Premio a Jesús Vera Irizarry

- ^ http://www.wapa.tv/noticias/entretenimiento/fallece-el-actor-miguel-angel-alvarez_20110116125055.html WAPA]

- ^ Bosque Pérez, Ramón (2006). Puerto Rico Under Colonial Rule. SUNY Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7914-6417-5. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ http://sembrandopatria.com/2009/01/01/fallecio-don-gilberto-martinez-sobreviviente-de-la-masacre-de-utuado/ Claridad]

- ^ The Imprisionement of Men and Women Fighting Colonialism, 1930 - 1940 Retrieved December 9, 2009.

- ^ a b c Public Law 600, Art. 3, 81st Congress of the United States of America, July 3, 1950

- ^ *José Trías Monge, Puerto Rico: The Trials of the Oldest Colony in the World (Yale University Press, 1997) ISBN 0-300-07618-5

- ^ "La obra jurídica del Profesor David M. Helfeld (1948-2008)'; by: Dr. Carmelo Delgado Cintrón

- ^ "Puerto Rican History". Topuertorico.org. January 13, 1941. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ^ Ley Núm. 282 del año 2006

- ^ La Gobernación de Jesús T. Piñero y la Guerra Fría

- ^ a b "Leyes de la Sexta y Octava Legislaturas Extraordinarias de la Decimosexta Asamblea Legislativa de Puerto Rico"; editorial = San Juan, División Imprenta

- ^ Puerto Rico history

- ^ El ataque Nacionalista a La Fortaleza. by Pedro Aponte Vázquez. Page 7. Publicaciones RENÉ. ISBN 978-1-931702-01-0

- ^ Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico-FBI files

- ^ El ataque Nacionalista a La Fortaleza; by Pedro Aponte Vázquez; Page 7; Publisher: Publicaciones RENÉ; ISBN 978-1-931702-01-0

- ^ New Yorlk Latino Journal

- ^ a b c Puerto Rico Uprising - 1950

- ^ NY Latino Journal

- ^ a b c d e f g h i www.pr-secretfiles.net/binders/HQ-105-11898_9_09_41.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Truman Library

- ^ a b c Jonah Raskin, Oscar Collazo: Portrait of a Puerto Rican Patriot (New York: New York Committee to Free the Puerto Rican Nationalist Prisoners, 1978).

- ^ Hunter & Bainbridge, p. 251

- ^ Hunter & Bainbridge, p. 251

- ^ Hunter & Bainbridge, p. 4

- Stephen Hunter and John Bainbridge, Jr., "American Gunfight: The Plot To Kill Harry Truman - And The Shoot-Out That Stopped It", Simon & Schuster (2005), ISBN 0-7432-6068-6.

- "Off The Record: The Private Papers of Harry S. Truman", Edited by Robert H. Ferrell, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, 1980, pp. 198–99