Conques

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (December 2008) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Conques | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | France |

| Region | Occitania |

| Department | Aveyron |

| Arrondissement | Rodez |

| Canton | Conques |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2008–2014) | Philippe Varsi |

| Area 1 | 30.51 km2 (11.78 sq mi) |

| Population (2008) | 281 |

| • Density | 9.2/km2 (24/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 12076 /12320 |

| Elevation | 221–663 m (725–2,175 ft) (avg. 442 m or 1,450 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

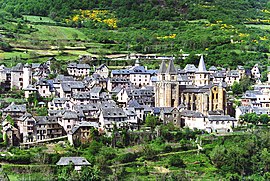

Conques (Concas in occitan) is a commune in the Aveyron department in southern France, in the Midi-Pyrénées region.

Geography

The village is located at the confluence of the Dourdou and Ouche rivers. It is built on a hillside and has classic narrow Medieval streets. As a result, large vehicles (such as buses) cannot enter the historic town centre but must park outside. Consequently, most day visitors enter on foot and, as at least one overnight visitor has observed, the majority of the tourists depart in the late afternoon, leaving the town much less crowded. The town was largely passed by in the nineteenth century, and was saved from oblivion by the efforts of a small number of dedicated people. As a result, the historic core of the town has very little construction dating from between 1800 and 1950, leaving the medieval structures remarkably intact. The roads have been paved, and modern-day utility lines are buried.

Abbey Church of Saint-Foy

The St. Foy abbey-church in Conques was a popular stop for pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostela, in what is now Spain. The original monastery building at Conques was an eighth-century oratory built by monks fleeing the Saracens in Spain.[1] The original chapel was destroyed in the eleventh-century in order to facilitate the creation of a much larger church [2] as the arrival of the relics of St. Foy caused the pilgrimage route to shift from Agen to Conques.[3] The second phase of construction, which was completed by the end of the eleventh-century, included the building of the five radiating chapels, the ambulatory with a lower roof, the choir without the gallery and the nave without the galleries.[4] The third phase of construction, which was completed early in the twelfth-century, was inspired by the churches of Toulouse and Santiago Compostela. Like most pilgrimage churches Conques is a basilica plan that has been modified into a cruciform plan.[5] Galleries were added over the aisle and the roof was raised over the transept and choir to allow people to circulate at the gallery level. The western aisle was also added to allow for increased pilgrim traffic.[6] The exterior length of the church is 59 meters. The interior length is 56 meters. the width of each transept is 4 meters. The height of the crossing tower is 26.40 meters tall.[5]

The main draw for medieval pilgrims at Conques were the remains of St. Foy, a martyred young woman from the fourth century. Her name has been assimilated into the general conception of 'Holy Faith.' The relics of St. Foy arrived in Conques through theft in 866. After unsuccessful attempts to acquire the relics of St. Vincent of Saragossa and then the relics of St. Vincent Pompejac in Agen they set their sights on the relics of St. Foy.[7] A monk from Conques posed as a loyal monk in Agen for nearly a decade in order to get close enough to the relics to steal them.[8]

The arches of the main aisle are simple rounded arches. These arches are echoed in the arches of the gallery which are half of the main arches' height with central supporting piers. Narrower versions of these arches are also found in the apse. The aisle around the apse is separated from the sanctuary by pillars and by the chapels which open up off of the transept.[5] There are three radiating chapels off of the apse [9] and two chapels off of the transept.[10] The side aisles are roofed with a barrel vault that was originally covered with stucco.[5] The nave at Conques is roofed with a continuous barrel vault which is 2 feet thick. The nave is divided into bays by piers which rise through the gallery and over the barrel vault. The piers of the naves are huge stone blocks laid horizontally and covered with either four half-columns or four pilasters. The interior of the church is 20.70 meters tall with the sense of verticality being intensified by the repeating pattern of half-columns and pilasters approaching the high altar. The barrel vault's outward thrust is met by the half barrels of the galleries which run the length of the nave and transept.[11]

The crossing dome is a delicate octagon set in square. Ribs radiate out from the center. Figures in the squinches are angels with realistic expressions and animated eyes.[5]

There are 212 columns in Conques with decorated capitals. The capitals are decorated with a variety of motifs including palm leaves, symbols, biblical monsters and scenes from the life of St. Foy.[12] On the fifth capital of the north side of the nave are two intricate and expressive birds. On the corresponding capital on the south side of the nave are flat and lifeless human figures. The figures appear to have a slight hunch, as if they are reacting to the weight of the arches above them.[5] The capitals functioned as didactic picture books for both monks and pilgrims.[2] Traces of color are still visible on a number of the columns.[9]

Light filters into Conques through the large windows under the groin vaults of the aisle and through the low windows under the half barrels of the galleries. The windows in the clerestory and the light from the ambulatory and radiating chapels focus directly onto the high altar. The nave receives direct light from the crossing tower.[13]

The ambulatory allowed pilgrims to glimpse into the sanctuary space through a metal grill.[14] The metal grill was created out of donated shackles from former prisoners who attributed their freedom to St. Foy.[15] The chains also have a number of symbolic meanings including reminding pilgrims of the ability of St. Foy to free prisoners and the ability of monks to free the penitent from the chains of sin. The stories associated with the ability of St. Foy to free the faithful follows a specific patter. Often a faithful pilgrim is captured and chained about the neck, they pray to St. Foy and are miraculously freed. The captor is sometimes tortured and then dismissed. The liberated pilgrims would then immediately travel to Conques and dedicate their former chains to St. Foy relaying their tale to all who would listen. As stories spread pilgrimage traffic increased.[7]

There is little exterior ornamentation on Conques except necessary buttresses and cornices. The exception to this is the Last Judgment tympanum located above the western entrance. As pilgrimages became safer and more popular the focus on penance began to wane. Images of doom were used to remind pilgrims of the purpose of their pilgrimage.[16] The tympanum appears to be later than the artwork in the nave. This is to be expected as construction on churches was usually begun in the east and completed in the west.[5] The tympanum depicts Christ in Majesty presiding over the judgment of the souls of the deceased. The cross behind Christ indicates he is both Judge and Savior. Archangel Michael and a demon weigh the souls of the deceased on a scale. The righteous go to Christ's right while the dammed go to Christ's left where they are eaten by a Leviathan and excreted into Hell. The torture of Hell are vividly depicted including poachers being roasted by the very rabbit they poached from the monastery.[17] The tympanum also provides an example of cloister whit. A bishop who governed the area of Conques but was not well liked by the monks of Conques is depicted as being caught in one of the nets of Hell.[16] The virtuous are depicted less colourfully.[18] The Virgin Mary, St. Peter and the pilgrim St. James stand on Christ’s left. Above their heads are scrolls depicting the names of the Virtues. Two gable shaped lintels act as the entrance into Heaven. In Heaven Abraham is shown holding close the souls of the righteous.[9] A pudgy abbot leads a king, possibly Charlemagne, into heaven. The tympanum was inspired by illuminated manuscripts and would have been fully colored, small traces of the color survive today.[9]

Conques is the home of many spectacular treasures. One of which is the famous ‘A’ of Charlemagne. The legend is that Charlemagne had twenty-four golden letters created to give to the monasteries in his kingdom. Conques received his ‘A’ indicating that it was his favorite.[19] This is only legend, while the ‘A’ exists it dates to circa 1100 and no other pieces of Charlemagne's alphabet have ever been found.[20] Conques is also home to an arm of St. George the Dragon Slayer. It is claimed that the arm at Conques is the arm with which he actually slayed the dragon. The golden statue reliquary of St. Foy dominated the treasury of Conques. Catching a glimpse of the reliquary was the main goal of the pilgrims who came to Conques. The head of the reliquary contains a piece of skull which has been authenticated.[21] The reliquary is a fifth-century roman head, possibly the head on an emperor, mounted on a wooden core covered with gold plating. Made in the latter half of the ninth-century the reliquary was 2 feet 9 inches tall. As miracles reportedly increased the gold crown, earrings, gold throne, filigree work and cameos and jewels, mostly donations from pilgrims, were added. In the fourteenth-century a pair of crystal balls and there mounts were added to the throne. Silver arms and hands were added in the sixteenth century. In the eighteenth-century bronze shoes and bronze plates on the knees were added.[2]

In the 19th century, the author and antiquary Prosper Mérimée, appointed the first Inspector of Historical Monuments, inspired thorough restorations.

The St. Foy abbey-church was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1998, as part of the World Heritage Sites of the Routes of Santiago de Compostela in France. Its Romanesque architecture, albeit somewhat updated in places, is displayed in periodic self-guided tour opportunities, especially of the upper level, some of which occur at night with live music and appropriately-adjusted light levels. A particularly interesting aspect of the church is the set of carvings of the "curieux" (the curious ones) who are peeking over the edges of the tympanum arch.

Population

| Year | 1793 | 1800 | 1806 | 1821 | 1831 | 1836 | 1841 | 1846 | 1851 | 1856 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 1055 | 1107 | 1234 | 1317 | 1309 | 1360 | 1418 | 1387 | 1117 | 1388 |

| Year | 1861 | 1866 | 1872 | 1876 | 1881 | 1886 | 1891 | 1896 | 1901 | 1906 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 1288 | 1301 | 1220 | 1267 | 1282 | 1286 | 1211 | 561 | 993 | 990 |

| Year | 1911 | 1921 | 1926 | 1931 | 1936 | 1946 | 1954 | 1962 | 1968 | 1975 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 902 | 755 | 725 | 709 | 686 | 647 | 561 | 529 | 479 | 420 |

| Year | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 404 | 362 | 302 | 281 |

Media

The late Hannah Green penned a non-fiction work about Conques and the church entitled Little Saint.

See also

References

- ^ Brockman, Norbert C. Encyclopedia of sacred places (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-59884-654-6.

- ^ a b c Stoddard, Whitney S. (1966). Art and Architecture in Medieval France. Boulder, Co.: Westview Press. p. 35. Cite error: The named reference "W. S. Stoddard, Art and Architecture (1966)" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Brockman, Norbert C. Encyclopedia of sacred places (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-59884-654-6.

- ^ Stoddard, Whitney S. (1966). Art and Architecture in Medieval France. Boulder, Co.: Westview Press. p. 35.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vernon, Eleanor (1963). "Romanesque Churches of the Pilgrimage Road". Gesta (Pre-Serial Issue): 13.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) Cite error: The named reference "Vernon" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ . p. 35.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Sinram, Marianne (1993). Derek Baker (ed.). Represenations of the Feminine in the Middle Ages. Academia Press. p. 227-290.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) Cite error: The named reference "Sinram (1993)" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Brockman, Norbert C. Encyclopedia of sacred places (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-59884-654-6.

- ^ a b c d Evans, Joan (1969). Art in Medieval France. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 23. Cite error: The named reference "Evans (1969)" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Stoddard, Whitney S. (1966). Monastery and Cathedral in France. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. p. 58.

- ^ . pp. 31, 33.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Brockman, Norbert C. Encyclopedia of sacred places (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-59884-654-6.

- ^ . pp. 32–33.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Lyman, Thomas W. (1988). "The Politics of Selective Eclecticism: Monastic Architecture, Pilgrimage Churches and "Resistance to Cluny". Gesta. 27 (1/2): 83–82.

- ^ Brockman, Norbert C. Encyclopedia of sacred places (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-59884-654-6.

- ^ a b Spivey, Nigel J. (2001). Enduring Creation: Art, Pain and Fortitude. Berkley, CA: University of California Press. p. 84. Cite error: The named reference "Spivey (2001)" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Brockman, Norbert C. Encyclopedia of sacred places (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-59884-654-6.

- ^ Brockman, Norbert C. Encyclopedia of sacred places (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-59884-654-6.

- ^ Brockman, Norbert C. Encyclopedia of sacred places (2nd ed. ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-59884-654-6.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Cynthia Hahn (2010). "Relics and Reliquaries: The Construction of Imperial Memory and Meaning, with Particular Attention to Treasuries at Conques, Aachen and Quedlinburg". In Robert A. Maxwell (ed.). Representing history, 900-1300: art, music, history. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 133-148. ISBN 978-0-271-03636-6.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Encyclopedia of Sacred Places. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-59884-654-6.

Gallery

-

Conques hermitage

-

Entrance gate to Conques - the Port du Barry

-

Conques rooftop vista

-

Abbey-church doorway carving

-

Abbey-church doorway carving detail

-

Abbey-church doorway carving detail

-

Abbey-church doorway carving detail

-

Abbey-church doorway carving detail

-

Abbey-church doorway carving detail

-

Abbey-church doorway carving detail

-

Conques panorama