Siege of Constantinople (717–718)

| Second Arab Siege of Constantinople | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab–Byzantine Wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Bulgar Khanate | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik Sulayman ibn Mu'ad Umar ibn Hubaira |

Leo III Tervel | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

120,000 men[2] 2,560 ships[3] | unknown | ||||||

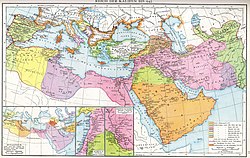

The Second Arab Siege of Constantinople in 717–718 was a combined land and sea effort by the Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate to take the capital city of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople. The campaign marked the culmination of twenty years of attacks and gradual Arab encroachment on the Byzantine borderlands, aided by internal Byzantine turmoil. The Arabs, led by Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik, invaded Byzantine Asia Minor in 716. Though they were initially hoping to exploit the ongoing Byzantine civil strife between Byzantine general Leo the Isaurian and Theodosius III, Leo tricked them and secured the Byzantine throne for himself.

After wintering in the western coastlands of Asia Minor, the Arab army crossed into Thrace in early summer 717 and built siege lines to blockade the city, which was protected by the massive Theodosian Walls. The Arab fleet, which accompanied the land army and was meant to complete the city's blockade by sea, was neutralized soon after its arrival by the Byzantine navy through the use of Greek fire, allowing Constantinople to be resupplied by sea, while the Arab army was crippled by famine and disease during the unusually hard winter that followed. In spring 718, two Arab fleets that were sent as reinforcements were destroyed by the Byzantines after their Christian crews defected, and an additional army sent overland through Asia Minor was ambushed and defeated. Coupled with attacks by the Bulgars on their rear, the Arabs were forced to raise the siege on 15 August 718. On its return journey, the Arab fleet was almost destroyed by natural disasters and Byzantine attacks.

The failure of the siege had wide-ranging repercussions. The rescue of Constantinople ensured the continued survival of Byzantium, while the Caliphate's strategic outlook was altered: although regular attacks on Byzantine territories continued, the goal of outright conquest was abandoned. The siege is also credited with having halted the Muslim advance into Europe, and is hence often considered one of the most decisive battles in history.

Background

Following the First Arab siege of Constantinople (674–678), the Arabs and Byzantines enjoyed a period of peace. After 680, the Umayyad Caliphate was in the throes of the Second Muslim Civil War and the Byzantines enjoyed an ascendancy in the East that enabled them to extort huge amounts of tribute from the Umayyad government in Damascus.[4] In 692, as the Muslim Civil War drew to its close with the Umayyad regime victorious, Emperor Justinian II (r. 685–695 and 705–711) re-opened hostilities. The result, however, was a series of Arab victories that led to the loss of control over Armenia and the Caucasian principalities, as well as the beginning of a gradual encroachment upon Byzantine lands. Year by year, the Caliphate's generals, usually members of the Umayyad family, launched raids into Byzantine territory and captured fortresses and towns.[5] After 712, the Byzantine defensive system began to show signs of collapse: Arab raids penetrated further and further into Asia Minor, the border fortresses were repeatedly attacked and sacked, and Byzantine reaction became more and more feeble.[6] In this, the Arabs were aided by the prolonged period of internal instability that followed the first deposition of Justinian II in 695. During this time, the Byzantine throne changed hands seven times in violent revolutions.[7] Nevertheless, as the Byzantinist Warren Treadgold comments, "the Arab attacks would in any case have intensified after the end of their own civil war ... With far more men, land and wealth than Byzantium, the Arabs had begun to concentrate all their strength against it. Now they threatened to extinguish the empire entirely by capturing its capital."[8]

Opening stages of the campaign

The Arab successes opened the way for a second assault on Constantinople, an undertaking already initiated under Caliph al-Walid I (r. 705–715). Following al-Walid's death, his brother and successor Sulayman (r. 715–717) took up the project with increased vigour, allegedly because of a prophecy that a Caliph bearing the name of a prophet would capture Constantinople; Sulayman (Solomon) was the only member of the Umayyad family to bear such a name. According to Syriac sources, the new Caliph even swore "to not stop fighting against Constantinople before having exhausted the country of the Arabs or to have taken the city".[9] The Umayyad forces began assembling at the plain of Dabiq north of Aleppo, under the direct supervision of the Caliph. As Sulayman was too sick to campaign himself, however, he entrusted the command of the expedition to his brother Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik.[10] The operation against Constantinople came at a time when the Umayyad state experienced a period of continuous expansion in east and west, with Muslim armies advancing into Transoxiana, India and Spain.[11]

Arab preparations, especially the construction of a large fleet, did not go unnoticed by the worried Byzantines. Emperor Anastasios II (r. 713–715) sent an embassy to Damascus under the patrician and urban prefect, Daniel of Sinope, ostensibly in order to plea for peace, but in reality to spy on the Arabs. Anastasius, in turn, began to prepare for the inevitable siege: the fortifications of Constantinople were repaired and equipped with ample artillery, while food stores were brought into the city and those inhabitants who could not stockpile food to last for three years evacuated from the city.[12] Anastasius also strengthened his navy and, in early 715, he dispatched it against the Arab fleet that had come to the shores of Lycia at Phoenix[13] to collect wood. At Rhodes, however, the Byzantine fleet, encouraged by the soldiers of the Opsician Theme, rebelled, killed their commander John the Deacon, and sailed north to Adramyttium. There, they declared a rather reluctant former tax collector emperor as Theodosios III.[14] Anastasius crossed over into Bithynia in the Opsician Theme to confront the rebellion, but the rebel fleet sailed on to Chrysopolis. From there, it launched attacks against Constantinople, until, in late summer, sympathizers within the capital opened up the gates to them. Anastasius held out at Nicaea for several months, until he agreed to resign and retire as a monk.[15] The accession of Theodosios, who by all accounts was both unwilling and incapable, as a puppet emperor of the Opsicians provoked the reaction of the other themes, especially the Anatolics and the Armeniacs under their respective strategoi (generals) Leo the Isaurian and Artabasdus.[16]

In these conditions of near-civil war, the Arabs began their carefully prepared advance. In September 715, the vanguard under general Sulayman ibn Mu'ad marched over Cilicia into Asia Minor, taking the strategic fortress of Loulon on its way, and wintered at Afik, an unidentified location near the western exit of the Cilician Gates. In early 716, Sulayma's army continued its advance into central Asia Minor. The Umayyad fleet under Umar ibn Hubaira also set sail and cruised along the Cilician coast, while Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik awaited developments with the main army in Syria.[17] The Arabs hoped that the disunity among the Byzantines would play to their advantage. Maslamah had already established contact with Leo the Isaurian. It is unknown what promises Leo may have made to Maslamah; the French scholar Rodolphe Guilland theorized that he offered to become a vassal of the Caliphate, although the Byzantine general intended to use the Arabs for his own purposes. In turn, Maslamah supported Leo hoping to maximize confusion and weaken the Empire, making his own task of taking Constantinople easier.[18]

As his first objective, Sulayman targeted the strategically important fortress of Amorium, which the Arabs intended to use as a base the next winter. Amorium had been left defenceless in the turmoil of the civil war and would have easily fallen to Sulayman's forces, but the Arabs chose to use the opportunity to bolster Leo's position as a counterweight to Theodosios, and offered the city terms of surrender if its inhabitants would acknowledge Leo as emperor. The citizens of Amorium complied, but still did not open their gates to the Arabs. Leo himself came to the vicinity with a handful of soldiers soon after and, after a series of ruses and negotiations, managed to install a garrison of 800 men in the town. The Arab army, thwarted in its objective and with supplies running low, withdrew. Leo himself was able to make good his escape to Pisidia and, in summer, with the support of Artabasdus, he was crowned emperor.[19][20]

Leo's success was a stroke of luck for Byzantium, since Maslamah with the main Arab army had in the meantime crossed the Taurus Mountains and was marching straight for Amorium. In addition, as the Arab general had not received any news of Leo's double-dealing, he did not devastate the territories he marched through—the Armeniac and Anatolic themes, whose governors he still believed to be his allies.[21] On meeting up with Sulayman's retreating army and learning what had transpired, Maslamah changed direction: he attacked Akroinon and from there marched to the western coastlands to spend the winter. On his way, he sacked Sardis and Pergamon. The Arab fleet wintered in Cilicia.[22] Leo, in the meantime, began his own march on Constantinople. He captured Nicomedia, where he found and captured, among other officials, Theodosios's son, and then marched to Chrysopolis. In spring 717, after short negotiations, he secured Theodosios's resignation and his recognition as emperor, entering the capital on 25 March. Theodosios and his son were allowed to retire to a monastery as monks and Artabasdus was rewarded by being promoted to the position of kouropalates and receiving the hand of Leo's daughter, Anna.[23]

Opposing forces

From the outset of their campaign, the Arabs had prepared for a major assault on Constantinople. The late 8th-century Syriac Zuqnin Chronicle reports that the Arabs were "innumerable", while the 12th-century Syriac chronicler Michael the Syrian mentions 200,000 men and 5,000 ships, a number certainly much inflated. The 10th-century Arab writer Al-Mas'udi mentions 120,000 troops, and the 9th-century account of Theophanes the Confessor 1,800 ships. Supplies for several years were hoarded, and siege engines and incendiary materials (naphtha) were carried along. The supply train alone is said to have numbered 12,000 men, 6,000 camels, and 6,000 donkeys, while according to the 13th-century historian Bar Hebraeus, the troops included 30,000 volunteers (mutawa) for the Holy War (jihad).[24] Whatever the true numbers, the attackers were considerably more numerous than the defenders; according to Treadgold, the Arab host may have outnumbered the entire Byzantine army.[2] Details on the composition of the Arab force are non-existent, except for the fact that it mostly consisted of and was led by Syrians and Jazirans of the elite ahl al-Sham ("Syrian army"), the main pillar of the Umayyad regime and veterans of the warfare against Byzantium.[25] Alongside Maslamah, Umar ibn Hubaira, Sulayman ibn Mu'ad, and Bakhtari ibn al-Hasan are mentioned as his lieutenants by Theophanes and the 10th-century historian Agapius of Hierapolis, while the anonymous 11th-century Kitab al-'Uyun replaces Bakhtari with Abdallah al-Battal.[26] Although the siege consumed a large part of the Caliphate's resources, it was still capable of launching raids against the Byzantine frontier in eastern Asia Minor during the siege's duration: in 717, Caliph Sulayman's son Daud captured a fortress near Melitene and in 718 Amr ibn Qais raided the frontier.[27] On the Byzantine side, the numbers are unknown. Aside from Anastasius II's preparations (which may have been neglected following his deposition),[28] the Byzantines could count on the assistance of the Bulgars, with whom Leo concluded a treaty that may have included terms of alliance against the Arabs.[29]

Siege

In early summer, Maslamah ordered his fleet to sail and join him and with his army crossed the Hellespont at Abydos into Thrace. The Arabs began their march on Cοnstantinople, thoroughly devastating the countryside, gathering supplies, and sacking the towns they came across.[30] In mid-July or mid-August,[1] the Arab army reached Constantinople and isolated it completely on land by building a double siege wall of stone, one facing the city and one facing the Thracian countryside, with their camp positioned between them. According to Arab sources, at this point Leo offered to ransom the city by paying a gold coin for every inhabitant, but Maslamah replied that there could not be peace with the vanquished, and that the Arab garrison of Constantinople had already been selected.[31]

The Arab fleet under Sulayman (often confused with the Caliph himself in the medieval sources) arrived on 1 September, anchoring at first near the Hebdomon. Two days later, Sulayman led his fleet into the Bosporus and the various squadrons began anchoring on the European and Asian suburbs of the city: one part sailed south of Chalcedon to the harbours of Eutropios and Anthemios to watch over the southern entrance of the Bosporus, while the rest of the fleet sailed into the strait, passed by Constantinople and began making landfall on the coasts between Galata and Kleidion, cutting the Byzantine capital's communication with the Black Sea. But as the Arab fleet's rearguard, twenty heavy ships with 2,000 marines, was passing the city, the southerly wind stopped and then reversed, drifting them towards the city walls, where a Byzantine squadron attacked them with Greek fire. Theophanes reports that some went down with all hands, while others, burning, sailed down to the Princes' Islands of Oxeia and Plateia. The victory encouraged the Byzantines and dejected the Arabs, who, according to Theophanes, had originally intended to sail to the sea walls the same night and try to scale them using the ships' steering paddles. The same night, Leo drew up the chain between the city and Galata, closing the entrance to the Golden Horn. The Arab fleet became reluctant to engage the Byzantines, and withdrew to the safe harbour of Sosthenion further north on the European shore of the Bosporus.[32]

The Arab army was well supplied with provisions, which were reportedly piled up in high mounds in their camp, and had even brought along wheat to sow and harvest in the next year. The failure of the Arab navy to effect a blockade of the city, however, meant that the Byzantines too could ferry in provisions. In addition, the Arab army had already devastated the Thracian countryside during its march to Constantinople, and could not rely on it for foraging. The Arab fleet and the second Arab army, which operated in the Asian suburbs of Constantinople, were able to bring in limited supplies to Maslamah's army.[33] As the siege drew into winter, negotiations were opened between the two sides, extensively reported by Arab sources but completely ignored by the Byzantine historians. According to the Arab accounts, Leo continued to play a double game with the Arabs. One version claims that he tricked Maslamah into handing over most of his grain supplies, while another claims that the Arab general was persuaded to burn them altogether, so as to show the inhabitants of the city that they faced an imminent assault and induce them to surrender.[34] The winter of 718 was extremely harsh; snow covered the ground for over three months. As the supplies in the Arab camp began to run out, a terrible famine broke out: the soldiers ate their horses, camels, and other livestock, and the bark, leaves and roots of trees. They swept the snow of the fields they had sown to eat the green shoots, and reportedly resorted even to cannibalism and eating their own excrement. The Arab army was ravaged by epidemics; the Lombard historian Paul the Deacon puts the number of their dead from hunger and disease at an incredible 300,000.[35]

The situation looked set to improve in spring when the new Caliph, Umar II (r. 717–720), sent two fleets to the besiegers' aid: 400 ships from Egypt under a commander named Sufyan and 360 ships from Africa under Izid, all laden with supplies and arms. At the same time, a fresh army began its march through Asia Minor to assist in the siege. When the new fleets arrived in the Sea of Marmara, they kept their distance from the Byzantines and their Greek fire and anchored on the Asian shore, the Egyptians in the Gulf of Nicomedia near modern Tuzla and the Africans south of Chalcedon (at Satyros, Bryas and Kartalimen). Most of the Arab fleets' crews were composed of Christian Egyptians, however, and they began deserting to the Byzantines upon their arrival. Notified by the Egyptians of the advent and disposition of the Arab reinforcements, Leo launched his fleet in an attack against the new Arab fleets. Crippled by the defection of their crews, and helpless against Greek fire, the Arab ships were destroyed or captured along with the weapons and supplies they carried. Constantinople was now safe from a seaborne attack.[36] On land too the Byzantines were victorious: their troops managed to ambush the advancing Arab army under a commander named Mardasan and destroy it in the hills around Sophon, south of Nicomedia.[37]

Constantinople could now be easily resupplied by sea and the city's fishermen recommenced their activities, as the Arab fleet did not sail forth from its anchorage again. Still suffering from hunger and pestilence, the Arabs lost a major battle against the Bulgars, who killed, according to Theophanes, 22,000 men. It is unclear, however, whether the Bulgars attacked the Arab encampment because of their treaty with Leo or whether the Arabs strayed into Bulgarian territory seeking provisions, as reported by the Syriac Chronicle of 846. Michael the Syrian mentions that the Bulgars participated in the siege from the beginning, with attacks against the Arabs on their way through Thrace and subsequently on their encampment, but this is not corroborated elsewhere.[38] The siege had clearly failed, and Caliph Umar sent orders to Maslamah to retreat. After thirteen months of siege, on 15 August 718, the Arabs departed. The date coincided with the feast of the Dormition of the Theotokos (Assumption of Mary), and it was to her that the Byzantines ascribed their victory. The retreating Arabs were not hindered or attacked on their return, but their fleet lost more ships in a storm in the Marmara Sea while other ships were set afire by ashes from the volcano of Santorini, and some of the survivors were captured by the Byzantines, so that Theophanes claims that only five vessels made it back to Syria.[39] Arab sources claim that altogether 150,000 Muslims perished during the campaign, a figure that, despite its obvious exaggeration, gives an idea of the scale of the defeat.[40]

Aftermath

The Arab failure was a severe blow to the Caliphate's military might. The Muslim fleet was annihilated and, although the land army did not suffer losses in the same degree, Umar is recorded as contemplating withdrawing from the recent conquests of Spain and Transoxiana, as well as a complete evacuation of Cilicia and other Byzantine territories that the Arabs had seized over the previous years. Although his advisors restrained him from such drastic actions, most Arab garrisons were withdrawn from the Byzantine frontier fortifications. In Cilicia, only Mopsuestia remained in Arab hands as a defensive bulwark to protect Antioch.[41] The Byzantines even recovered some territory in western Armenia for a time. In 719, the Byzantine fleet raided the Syrian coast and burned down the port of Laodicea and, in 720 or 721, the Byzantines attacked and sacked Tinnis in Egypt.[42] Leo also restored control over Sicily, where news of the Arab siege of Constantinople and expectations of the city's fall had prompted the local governor to declare an emperor of his own, Basil Onomagoulos. It was during this time, however, that effective Byzantine control over Sardinia and Corsica ceased.[43] Besides this, the Byzantines failed to exploit their success in launching attacks of their own against the Arabs. In 720, after a hiatus of two years, Arab raids against Byzantium resumed, although now they were no longer directed at conquest, but rather seeking booty. The Arab attacks would intensify again over the next two decades, until the major Byzantine victory at the Battle of Akroinon in 740. After military defeats elsewhere and internal instability which culminated in the Abbasid Revolution, the age of Muslim expansion came to an end.[44]

Historical assessment and impact

The second Arab siege of Constantinople was far more dangerous for Byzantium than the first, since it was a direct, well-planned attack on the Byzantine capital. In 717–718, the Arabs tried to cut off the city completely, rather than limiting themselves to a loose blockade as in 674–678.[27] It represented an effort by the Caliphate to "cut off the head" of the Byzantine Empire, after which the remaining provinces, especially in Asia Minor, would be easy to capture.[45] The Arab failure was chiefly due to logistics, as they were operating too far from their bases in Syria. The superiority of the Byzantine navy and of Greek fire, the strength of Constantinople's fortifications, and the skill of Leo III in deception and negotiations also played important roles.[46]

In the long term, the failure of the Arab siege led to a profound change in the nature of warfare between Byzantium and the Caliphate. The Muslim goal of conquest of Constantinople was effectively abandoned and the frontier of the two empires stabilized along the line of the Taurus and Antitaurus Mountains, over which both sides launched regular raids and counter-raids. In this incessant border warfare, frontier towns and fortresses changed hands frequently, but the general outline of the border remained unaltered for over two centuries, until the Byzantine conquests of the 10th century.[47] On the Muslim side, the raids themselves soon acquired an almost ritual character, as a demonstration of the continuing jihad and a symbol of the Caliph's role as the leader of the Muslim community.[48]

The outcome of the siege was also of considerable macrohistorical importance. The Byzantine capital's survival preserved the Empire as a bulwark against Islamic expansion into Europe until the 15th century, when it fell to the Ottoman Turks. The successful defence of Constantinople has been linked with the Battle of Tours in 732 as stopping Muslim expansion into Europe. As military historian Paul K. Davis writes, "By turning back the Moslem invasion, Europe remained in Christian hands, and no serious Moslem threat to Europe existed until the fifteenth century. This victory, coincident with the Frankish victory at Tours (732), limited Islam's western expansion to the southern Mediterranean world."[49] Thus the historian John B. Bury calls 718 "an ecumenical date", while the Greek historian Spyridon Lambros likened the siege to the Battle of Marathon and Leo III to Miltiades.[50] Consequently, military historians often include the siege in lists of the "decisive battles" of world history.[51]

Cultural impact

Among the Arabs, the 717–718 siege became the most famous of their expeditions against Byzantium. Several accounts survive, but most were composed at later dates and are semi-fictional and contradictory. In later Arab legend, the defeat was transformed into a victory: Maslamah departed only after symbolically entering the Byzantine capital on his horse accompanied by thirty riders, where Leo received him with honour and led him to the Hagia Sophia. After Leo paid homage to Maslamah and promised tribute, Maslamah and his troops—30,000 out of the original 80,000 that set out for Constantinople—departed for Syria.[52] The tales of the siege influenced similar episodes in Arabic epic literature. A siege of Constantinople is found in the tale of Omar bin al-Nu'uman and his sons in the Thousand and One Nights, while both Maslamah and the Caliph Sulayman appear in a tale of the Hundred and One Nights from the Maghreb. The commander of Maslamah's bodyguard, Abdallah al-Battal, became a celebrated figure in Arab and Turkish poetry as "Battal Gazi" for his exploits in the Arab raids of the next decades. Similarly, the 10th-century epic Delhemma, related to the cycle around Battal, gives a fictionalized version of the 717–718 siege.[53]

Later Muslim and Byzantine tradition also ascribed the building of Constantinople's first mosque, near the city's praetorium, to Maslamah. In reality, the mosque near the praetorium was probably erected in about 860, as a result of an Arab embassy in that year.[54] Ottoman tradition also ascribed the building of the Arap Mosque (located outside Constantinople proper in Galata) to Maslamah, although it erroneously dated this to around 686, probably confusing Maslamah's attack with the first Arab siege in the 670s.[55]

Eventually, following their repeated failures before Constantinople, and the continued resilience of the Byzantine state, the Muslims began to project the fall of Constantinople to the distant future. Thus the city's fall came to be regarded as one of the signs of the arrival of the end times in Islamic eschatology.[56]

References

Citations

- ^ a b Theophanes the Confessor gives the date as 15 August, but this is probably meant to mirror the Arabs' departure date in the next year. Patriarch Nikephoros I records the duration of the siege as 13 months, implying that it began on 15 July. Mango & Scott 1997, p. 548 (Note #16); Guilland 1959, pp. 116–118.

- ^ a b Treadgold 1997, p. 346.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 346–347.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 81–82, 97–106.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 31; Haldon 1990, p. 72; Lilie 1976, pp. 107–120.

- ^ Haldon 1990, p. 80; Lilie 1976, pp. 120–122, 139–140.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 31; Lilie 1976, p. 140; Treadgold 1997, pp. 345–346.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 345.

- ^ Brooks 1899, pp. 20–21; El-Cheikh 2004, p. 65; Guilland 1959, p. 110; Lilie 1976, p. 122; Treadgold 1997, p. 344.

- ^ Guilland 1959, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 73.

- ^ Mango & Scott 1997, p. 534; Lilie 1976, pp. 122–123; Treadgold 1997, pp. 343–344.

- ^ This may be a confusion with Phoenicia (modern Lebanon), famed for its cedar forests. Lilie 1976, p. 123 (Note #62).

- ^ Haldon 1990, p. 80; Mango & Scott 1997, pp. 535–536; Lilie 1976, pp. 123–124; Treadgold 1997, p. 344.

- ^ Haldon 1990, pp. 80, 82; Mango & Scott 1997, p. 536; Treadgold 1997, pp. 344–345.

- ^ Lilie 1976, p. 124; Treadgold 1997, p. 345.

- ^ Guilland 1959, p. 111; Mango & Scott 1997, p. 538; Lilie 1976, pp. 123–125.

- ^ Guilland 1959, pp. 118–119; Lilie 1976, p. 125.

- ^ Mango & Scott 1997, pp. 538–539; Lilie 1976, pp. 125–126; Treadgold 1997, p. 345.

- ^ For a detailed examination of Leo's negotiations with the Arabs before Amorium in Byzantine and Arab sources, cf. Guilland 1959, pp. 112–113, 124–126.

- ^ Guilland 1959, p. 125; Mango & Scott 1997, pp. 539–540; Lilie 1976, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Guilland 1959, pp. 113–114; Mango & Scott 1997, pp. 540–541; Lilie 1976, p. 127; Treadgold 1997, p. 345.

- ^ Haldon 1990, pp. 82–83; Mango & Scott 1997, pp. 540, 545; Lilie 1976, pp. 127–128; Treadgold 1997, p. 345.

- ^ Guilland 1959, p. 110; Kaegi 2008, pp. 384–385; Treadgold 1997, p. 938 (Note #1).

- ^ Guilland 1959, p. 110; Kennedy 2001, p. 47.

- ^ Canard 1926, pp. 91–92;Guilland 1959, p. 111.

- ^ a b Lilie 1976, p. 132.

- ^ Lilie 1976, p. 125.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 347.

- ^ Brooks 1899, p. 23; Mango & Scott 1997, p. 545; Lilie 1976, p. 128; Treadgold 1997, p. 347.

- ^ Guilland 1959, p. 119; Mango & Scott 1997, p. 545; Lilie 1976, pp. 128–129; Treadgold 1997, p. 347.

- ^ Guilland 1959, pp. 119–120; Mango & Scott 1997, pp. 545–546; Lilie 1976, p. 128; Treadgold 1997, p. 347.

- ^ Lilie 1976, p. 129; Treadgold 1997, p. 347.

- ^ Brooks 1899, pp. 26–28, 30; Lilie 1976, p. 129.

- ^ Brooks 1899, pp. 28–29; Guilland 1959, pp. 122–123; Mango & Scott 1997, p. 546; Lilie 1976, pp. 129–130; Treadgold 1997, p. 347.

- ^ Guilland 1959, p. 121; Mango & Scott 1997, pp. 546, 548; Lilie 1976, p. 130; Treadgold 1997, pp. 347–348.

- ^ Guilland 1959, p. 122;Mango & Scott 1997, p. 546; Lilie 1976, pp. 130–131; Treadgold 1997, p. 348.

- ^ Canard 1926, pp. 90–91; Guilland 1959, pp. 122, 123; Mango & Scott 1997, p. 546; Lilie 1976, p. 131.

- ^ Mango & Scott 1997, p. 550; Treadgold 1997, p. 349.

- ^ Haldon 1990, p. 83.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 33–34; Lilie 1976, pp. 132–133; Treadgold 1997, p. 349.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 287 (Note #133); Lilie 1976, p. 133; Treadgold 1997, p. 349.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 347, 348.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 34–35, 117–236; Haldon 1990, p. 84; Kaegi 2008, pp. 385–386; Lilie 1976, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 105; Kaegi 2008, p. 385; Lilie 1976, p. 141; Treadgold 1997, p. 349.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 104–106; Haldon 1990, pp. 83–84; El-Cheikh 2004, pp. 83–84; Toynbee 1973, pp. 107–109.

- ^ El-Cheikh 2004, pp. 83–84; Kennedy 2001, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Davis 2001, p. 99.

- ^ Guilland 1959, p. 129.

- ^ Crompton 1997, pp. 27–28; Davis 2001, pp. 99–102; Fuller 1987, pp. 335ff.; Regan 2002, pp. 44–45; Tucker 2010, pp. 94–97.

- ^ Canard 1926, pp. 99–102; El-Cheikh 2004, pp. 63–64; Guilland 1959, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Canard 1926, pp. 112–121; Guilland 1959, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Canard 1926, pp. 94–99; El-Cheikh 2004, p. 64; Guilland 1959, pp. 132–133; Hasluck 1929, p. 720.

- ^ Canard 1926, p. 99; Hasluck 1929, pp. 718–720.

- ^ Canard 1926, pp. 104–112; El-Cheikh 2004, pp. 65–70; Hawting 2000, p. 73.

Sources

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-1827-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brooks, E. W. (1899). "The Campaign of 716–718 from Arabic Sources". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. XIX. The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies: 19–33.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|journal=|ref=harv(help) - Canard, Marius (1926). "Les expéditions des Arabes contre Constantinople dans l'histoire et dans la légende". Journal Asiatique (in French) (208): 61–121. ISSN 0021-762X.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crompton, Samuel Willard (1997). 100 Battles That Shaped World History. San Mateo, California: Bluewood Books. ISBN 978-0-912517-27-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davis, Paul K. (2001). "Constantinople: August 717–15 August 718". 100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 99–102. ISBN 0-19-514366-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - El-Cheikh, Nadia Maria (2004). Byzantium Viewed by the Arabs. Cambridge, Massachusets: Harvard Center for Middle Eastern Studies. ISBN 0-932885-30-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fuller, J. F. C. (1987). A Military History of the Western World, Volume 1: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto. New York City, New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-30-680304-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Guilland, Rodolphe (1959). "L'Expedition de Maslama contre Constantinople (717-718)". Études byzantines (in French). Paris: Publications de la Faculté des Lettres et Sciences Humaines de Paris: 109–133. OCLC 603552986.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Haldon, John F. (1990). Byzantium in the Seventh Century: The Transformation of a Culture. Revised Edition. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521319171.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hasluck, F. W. (1929). "LVII. The Mosques of the Arabs in Constantinople". Christianity and Islam Under the Sultans, Volume 2. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press. pp. 717–735.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hawting, G.R. (2000). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750 (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom and New York City, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24072-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kaegi, Walter E. (2008). "Confronting Islam: Emperors versus Caliphs (641–c. 850)". In Shepard, Jonathan (ed.). The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire c. 500–1492. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 365–394. ISBN 978-0-52-183231-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-45853-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lilie, Ralph-Johannes (1976). Die byzantinische Reaktion auf die Ausbreitung der Araber. Studien zur Strukturwandlung des byzantinischen Staates im 7. und 8. Jhd (in German). Munich, Germany: Institut für Byzantinistik und Neugriechische Philologie der Universität München.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mango, Cyril; Scott, Roger (1997). The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor. Byzantine and Near Eastern History, AD 284–813. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822568-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Regan, Geoffrey (2002). Battles That Changed History: Fifty Decisive Battles Spanning over 2,500 Years of Warfare. London, United Kingdom: Andre Deutsch. ISBN 978-0-233-05051-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Toynbee, Arnold J. (1973). Constantine Porphyrogenitus and His World. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-215253-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). Battles That Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-429-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Radic, Radivoj (18 August 2008). "Two Arabian sieges of Constantinople (674-678; 717/718)". Encyclopedia of the Hellenic World, Constantinople. Athens, Greece: Foundation of the Hellenic World. Retrieved 14 July 2012.