Asiatic cheetah

| Asiatic Cheetah[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Portrait of an Asiatic Cheetah from India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | A. j. venaticus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Acinonyx jubatus venaticus (Griffith, 1821)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Acinonyx jubatus raddei | |

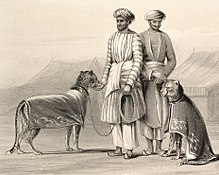

The Asiatic Cheetah ("cheetah" from Hindi चीता cītā, derived from Sanskrit word chitraka meaning "speckled") (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) is now also known as the Iranian Cheetah, as the world's last few are known to survive mostly in Iran. Although recently presumed to be extinct in India, it is also known as the Indian Cheetah. During British colonial times in India it was famous by the name of Hunting-Leopard,[3] a name derived from the ones that were kept in captivity in large numbers by the Indian royalty to hunt wild antelopes with. (In some languages all cheetah species are still called exactly that; i.e. Dutch: jachtluipaard.)

The Asiatic Cheetah is a critically endangered[2] subspecies of the Cheetah found today only in Iran, with some occasional sightings in Balochistan, Pakistan. It lives in its vast central desert in fragmented pieces of remaining suitable habitat. Although once common, the animal was driven to extinction in other parts of Southwest Asia from Arabia to India including Afghanistan. Estimates based on field surveys over ten years indicate a remaining population of 70 to 100 Asiatic Cheetahs, most of them in Iran.

The Asiatic Cheetah separated from its African relative between 32,000 and 67,000 years ago.[4][5][6][7] Along with the Eurasian Lynx and the Persian Leopard, it is one of three remaining species of large cats in Iran today.[8]

Anatomy and morphology

The Cheetah is the fastest land animal in the world.[9] The head and body of the adult Asiatic Cheetah measure from 112 to 135 cm with a tail length between 66 and 84 cm. It can weigh from 34 to 54 kg, but the male is slightly larger than the female.

Ecology and life history

Habitat

Cheetahs thrive in open lands, small plains, semi-desert areas, and other open habitats where prey is available. The Asiatic Cheetah is found in the Kavir desert region of Iran, which includes parts of the Kerman, Khorasan, Semnan, Yazd, Tehran, and Markazi provinces. The Asiatic Cheetah also seems to survive in the dry open Balochistan province of Pakistan where adequate prey is available. The cheetah's habitat is under threat from desertification, increasing agriculture, residential settlements, and declining prey — caused by hunting and degradation in pastures by overgrazing from introduced livestock.[10] Females, unlike males, do not establish a territory, which means they "travel" within their habitats, sometimes migrating long distances.[11]

Feeding ecology

The Asiatic cheetah preys on small antelopes. In Iran, its diet consists mainly of Jebeer Gazelle (also called Chinkara), Goitered Gazelle, wild sheep, Wild Goat, and Cape Hare. The main threat to the species is loss of their primary prey species due to poaching and grazing competition with domestic livestock. A study published in 2012 indicated that hares and rodents, while forming part of the cheetah's diet, are not a significant source of nutrition due to their small size and difficulty of being caught.[12] Habitat loss from mining development and poaching of Asiatic Cheetahs also threaten their populations in Iran. The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and the Department of Environment, Iran (DoE) began a collaring project for Asiatic Cheetahs in the fall of 2006.[13][14]

In India, prey was formerly abundant. Before its extinction in the country, the cheetah fed on the Blackbuck, the Chinkara, and sometimes the Chital and the Nilgai.

...is in low, isolated, rocky hills, near the plains on which live antelopes, its principal prey. It also kills gazelles, nilgai, and, doubtless, occasionally deer and other animals. Instances also occur of sheep and goats being carried off by it, but it rarely molests domestic animals, and has not been known to attack men. Its mode of capturing its prey is to stalk up to within a moderate distance of between one to two hundred yards, taking advantage of inequalities of the ground, bushes, or other cover, and then to make a rush. Its speed for a short distance is remarkable far exceeding that of any other beast of prey, even of a greyhound or kangaroo-hound, for no dog can at first overtake an Indian antelope or a gazelle, either of which is quickly run down by C. jubatus, if the start does not exceed about two hundred yards. General McMaster saw a very fine hunting-leopard catch a black buck that had about that start within four hundred yards. It is probable that for a short distance the hunting-leopard is the swiftest of all mammals.

— Blanford writing on the Asiatic Cheetah in India quoted by Lydekker[3]

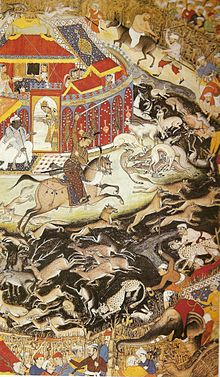

Evolutionary history

Asiatic Cheetahs once ranged from Arabia to India, through Iran, central Asia,[15] Afghanistan, and Pakistan. In Iran and the Indian subcontinent, it was particularly numerous. Cheetahs are the only big cat that can be tamed and trained to hunt gazelle. The Mughal Emperor of India, Akbar, was said to have had 1,000 cheetahs at one time, something depicted in many Persian and Indian miniature paintings. The numerous constraints regarding the Cheetah’s conservation contribute to its general susceptibility and its very complex conservation requirements, e.g., its low fertility rate, the high mortality rate of the cubs due to genetic factors, and the fact that females are the ones who select mates, have been reasons why captive breeding has had such a poor record. A Cheetah-specific issue is its limited gene pool. All living Cheetahs have very limited genetic diversity due to a near-extinction event some 12,000 years ago. The Cheetah will not be a “robust, vigorous species anytime in the foreseeable future"[16]

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the species was already heading for extinction in many areas. The last physical evidence of the Asiatic Cheetah in India was three shot by the Maharajah of Surguja in 1947 in eastern Madhya Pradesh. By 1990, the Asiatic Cheetah appeared to survive only in Iran. Estimated to number more than 200 during the 1970s, more recently Iranian biologist Hormoz Asadi estimated the remaining number to be between 50 and 100. Figures for 2005-2006 suggest between 50 and 60 in the wild. Most of these Asiatic Cheetahs live in Iran in the Kavir desert. Continuous field surveys, along with 12,000 nights of camera trapping inside its fragmented Iranian desert habitats, are used to estimate the population size. Using 80 camera traps placed throughout the Dasht-e Kavir plateau, Iranian researchers obtained images of 76 individual cheetahs over the course of ten years.[17]

A remnant population inhabits the dry terrain covering the border of Iran and Pakistan. In the areas in which the cheetah lives, locals say they have not seen it for more than fifteen years.[18]

Sub-species level differentiation

Asiatic cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) have for a long time been classified as a sub-species of the cheetah. In September 2009, Stephen J. O'Brien from the Laboratory of Genomic Diversity of the National Cancer Institute said that the Asiatic cheetah was genetically identical to the African Cheetah and had separated about 5,000 years ago – not enough time for a sub-species level differentiation.[19][20] In comparison, he said that the Asian and African lion subspecies were separated some 100,000 years ago, and the African and Asian leopard subspecies 169,000 years ago.

However, a much more detailed five-year genetic study involving the gathering of DNA samples from the wild, zoos and museums in eight countries published in Molecular Ecology (Journal) on 8 January 2011, concluded that African and Asiatic cheetahs were genetically very distinct. Molecular sequence comparisons suggest that they separated between 32,000 to 67,000 years ago and that subspecies level differentiation had occurred.[4][5][6][7] The populations in Iran are the last remaining representatives of the Asian lineage.[4]

Conservation

Following the Iranian Revolution of 1979, wildlife conservation was given a lower priority.[21] The Asiatic Cheetah and its principal prey, gazelles, were hunted, resulting in a rapid decline. Its prey was also pushed out as herders entered game reserves with their herds.[12] As a result, the Asiatic Cheetah is now listed as critically endangered in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. Some surveys by Asadi in the latter half of 1997 show that urgent action is required to rehabilitate wildlife populations, especially gazelles and their habitat if the Asiatic Cheetah is to survive. They are confined to the desert areas around Dasht-e-Kavir in the eastern half of Iran. Most live in five sanctuaries: Kavir National Park, Touran National Park, Bafq Protected Area, Daranjir Wildlife Reserve, and Naybandan Wildlife Reserve.[22] Photos from camera traps show that some females travel long distances between reserves–one female migrated 130 km, a journey which included crossing a railway and two major roads.[11]

Threats

Land-use change has been a major factor in the Cheetah's ecosystem. Persecution, habitat degradation and fragmentation, desertification, and direct killing of wildlife that the Cheetah preys upon, particularly game animals and off-take for commercial uses through poaching[23] are all factors responsible for the chronic decline of the Cheetah in Iran. According to the Iranian Department of Environment this degradation occurred mainly between 1988 and 1991.

The Asiatic Cheetah exists in very low numbers, divided into widely separated populations. Its low density makes it more likely to be affected by a lack of prey through livestock overgrazing and antelope hunting, coupled with direct persecution from humans. While protected areas comprise a key component of the cheetah's habitat, management needs to be improved. Widespread hunting of this animal and its prey species along with conversion of its grassland habitat to farmland has eliminated it completely from its entire range in southwest Asia and India.

Mining of coal, opium, and iron: Coal, copper, and iron are the three important goods that have been mined in the Cheetah's habitat in three different regions in central and eastern Iran. It is estimated that the two regions for coal (Nayband) and iron (Bafq) have the largest Cheetah population outside the protected areas. Mining itself is not a direct threat to Cheetahs; road construction and the resulting traffic have made the Cheetah accessible to humans, including poachers. The Iranian border regions to Afghanistan and Pakistan (Baluchistan province) have been, and still are, major passages for armed outlaws and opium smugglers who distribute their “goods” in the central and western regions of Iran; they must pass through the Cheetah habitat. According to Asada in 1997, the region suffers from uncontrolled hunting throughout the desert and the governments of the three countries cannot establish control.[24] There is no reliable information regarding the present situation in this region.

Conservation efforts

Iran's Department of the Environment, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Global Environment Facility (GEF) have launched the Conservation of the Asiatic Cheetah Project (CACP) designed to preserve and rehabilitate the remaining areas of Cheetah habitat left in Iran.[25]

Training course for herders: It is estimated that ten Cheetahs live in the Bafq Protected Area. According to the Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), herders are considered as a significant target group which generally confuses the Cheetah with other similar-sized carnivores, including wolf, leopard, striped hyena, and even caracal and wild cat. On the basis of the results of conflict assessment, a specific Herders Training Course was developed in 2007, in which they learned how to identify the cheetah as well as other carnivores, since these were the main causes for livestock kills. These courses were a result of cooperation between UNDP/GEF, Iran’s Department of Environment, ICS, and the councils of five main villages in this region.

Cheetah Friends: Another incentive in the region is the formation of young core groups of Cheetah Friends, who after a short instructive course, are able to educate people and organize Cheetah events and become an informational instance in Cheetah matters for a number of villages. Young people have expressed growing interest in the issue of Cheetah and other wildlife conservation.

Ex-situ conservation: India, where the Asiatic Cheetah is now extinct, is interested in cloning the cheetah to reintroduce it to the country,[26] and it was claimed that Iran - the donor country - was willing to participate in the project.[27] Later, however, Iran refused to send a male and female cheetah or to allow experts to collect tissue samples from a cheetah kept in a zoo there.[28] In 2009, the Indian government considered reintroducing Cheetahs through importing from Africa through captive breeding.[29]

Semi-Captive Breeding and Research Center of Iranian cheetah, Semnan province

In February 2010 Mehr News Agency, Payvand Iran News released the photos of an Asiatic/Iranian Cheetah in a seemingly large compound within natural habitat enclosed by chain link fence, this location was reported in this news article to be the "Semi-Captive Breeding and Research Center of Iranian Cheetah" in Iran's Semnan province. The Asiatic Cheetah pictured had a winter coat with long and furry hair.[30] Another news report stated that the centre is home to about ten Asiatic Cheetahs in a semi-wild environment protected by wire fencing all around.[31]

In January 2010, Iran and Russia jointly announced plans to revive both the Asiatic Cheetah and the Amur Tiger species (which has been shown to be genetically similar to the extinct Caspian Tiger of the area[32]) in and around the Caspian region through a joint project in the near future.[33]

Re-wilding project in India

Cheetahs have been known to exist in India for a very long time but hunting and other factors led to their extinction in the country in the 1940s. The Indian government planned a re-wilding project for Cheetahs. The article in TOI, Page 11, Thursday, 9 July 2009, suggests the importation of Cheetahs into India where they would be bred in captivity. Minister of Environment and Forests, Jairam Ramesh, told the Rajya Sabha on 7 July 2009 that, "The cheetah is the only animal that has been described extinct in India in the last 100 years. We have to get them from abroad to repopulate the species." He was responding to a calling attention notice from Rajiv Pratap Rudy of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). "The plan to bring back the Cheetah which fell to indiscriminate hunting and complex factors like a fragile breeding pattern is audacious given the problems besetting tiger conservation." Two naturalists, Divya Bhanusinh and MK Ranjit Singh, suggested the idea of importing cheetahs from Africa. According to the plan, they would be bred in captivity in India and eventually released into the wild.

In September 2009, at a cheetah reintroduction workshop organized in India, Stephen J. O'Brien asserted that the African and Asiatic cheetahs were genetically identical and had separated only 5,000 years ago. Cheetah expert Laurie Marker of the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) and other wildlife experts advised the Indian Government that for reintroduction purposes, India should source the Cheetah from Africa where they were much more numerous instead of trying to have some removed from the critically endangered low population in Iran. Participants included India's Union Minister of State for Environment and Forests, Jairam Ramesh, chief wildlife wardens of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, officials of the environment ministry, cheetah experts from across the globe, representatives from the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) including Yadvendradev Jhala, and IUCN, an international conservation NGO. The conference was organized by the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI).[19][20]

In May 2012, India's Supreme Court suspended attempts to introduce African cheetahs following the publication of newer genetic evidence, which suggests that the Asian and African cheetahs separated between 32,000 and 67,000 years ago.[34]

Russia–Iran re-population project

In light of genetic studies showing that the Russian or Amur Tiger is genetically identical to the extinct Caspian Tiger – habitat fragmentation having separated the two within the last century – Russia offered tigers to Iran to repopulate northern Iran, in exchange for Asiatic Cheetahs to repopulate the northern Caucasus region. There are many more Russian or Amur Tigers in the wild than surviving Asiatic Cheetah and, while there is a healthy population of Russian Tigers in the captive breeding program in the zoos,[35][36] there is no captive breeding population of the Asiatic Cheetah in any zoo.[32][33] International Cheetah experts advised that no individuals should be withdrawn from Iran at this stage because their limited gene pool would be reduced further.[37][38]

References

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 533. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Template:IUCN2008

- ^ a b Lydekker, R. A. 1893-94. The Royal Natural History. Volume 1

- ^ a b c Charruau P; C Fernandes; P Orozco-Terwengel; J Peters; L Hunter; H Ziaie; A Jourabchian; H Jowkar; G Schaller; S Ostrowski (2011). "Phylogeography, genetic structure and population divergence time of cheetahs in Africa and Asia: evidence for long-term geographic isolates". Molecular Ecology. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04986.x/pdf.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Three distinct cheetah populations, but Iran's on the brink". USA TODAY. 18 January 2011.

- ^ a b "Asian cheetahs racing toward extinction". Scientific American. 24 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ a b "The Need for Conservation of Asiatic Cheetahs". ScienceDaily. 17 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ "United Nation Development Program UNDP" (PDF).

- ^ Milton, H. 1959. Motions of cheetah and horse. Journal of Mammalogy

- ^ "Cheetah Habitats in Iran". Conservation of Asiatic Cheetah project (CACP). Archived from the original on 2 July 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Cheetah in Iran migrating between 2 reserves 130 kilometres apart". Wildlife Extra. June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Bardo, Matt (26 September 2012). "Asiatic cheetahs forced to hunt livestock". BBC News.

- ^ "Studies of the Asiatic Cheetah in Iran". Saving Wild Places. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ "Iran Cheetah Project". Wildlife Conservation Society, New York. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ Mallon DP. 2007. Cheetahs in Central Asia: A historical summary; CAT NEWS 46:4-7 (Pdf [1])

- ^ Gugliotta, G. 2008. Rare breed. Smithsonian 38(12):38

- ^ Smith, Roff (November 2012). "Cheetahs on the Edge". National Geographic.

- ^ "Asiatic cheetah". felidae.org.

- ^ a b "Experts eye African cheetahs for reintroduction, to submit plan". IANS. Thaindian. 10 September 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ a b "Workshop on cheetah relocation begins, views differ". PTI. Times of India. 9 September 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ "Cheetahs in Iran; the last stronghold of the Asiatic cheetah". Wildlife Extra. Archived from the original on 15 November 2009.

- ^ *Farhadinia MS. 2004. The last stronghold: cheetah in Iran. Cat News 40:11-4.

- ^ "2008 Conservation of the Asiatic Cheetah". UNDP.

- ^ Asadi, H. 1997. The environmental limitations and future of the Asiatic cheetah in Iran.

- ^ "Conservation of the Asiatic Cheetah Project" (PDF). IUCN.

{{cite web}}:|archive-url=is malformed: timestamp (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pros and Cons of inbreeding - See footnotes on page

- ^ Internet Archive Copy (Wayback Machine): News - Cheetah cloning project gets a boost

- ^ "Mullas' regime says "No" to cloning of cheetah".

- ^ "Extinct in India, Cheetah may be imported". The Times Of India. 8 July 2009.

- ^ "Photos: Saving the Iranian Cheetah from Extinction; Photos by Yuness Khani". Mehr News Agency. Payvand Iran News. 25 February 2010.

- ^ "Asiatic Cheetah on The Brink of Extinction - Less Than one Hundred Asiatic Cheetahs Survive in the World". Hamsayeh.net. 27 February 2010.

- ^ a b "Mitochondrial Phylogeography Illuminates the Origin of the Extinct Caspian Tiger and Its Relationship to the Amur Tiger". plosone.org.

- ^ a b "Iran, Russia Hope to Revive Extinct Big Cats". Payvand. 9 January 2010.

- ^ "India court suspends plan to reintroduce cheetah". BBC News. 9 May 2012.

- ^ Walker, Matt (2 July 2009). "Amur tigers on 'genetic brink". BBC News.

- ^ Miquelle, P. (23 June 2009). "In situ population structure and ex situ representation of the endangered Amur tiger". Molecular Ecology, Volume 18 Issue 15, Pages 3173 - 3184.

{{cite web}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help) - ^ "Experts eye African cheetahs for reintroduction, to submit plan". ICT by IANS. 11 September 2009. Archived from the original on 17 June 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Iran warned against cheetah transfer". Press TV Iran. 5 April 2010.

External links

- Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS) - A non-profit organisation set up to save the Asiatic cheetah.

- The Asiatic or Iranian Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) - by: Norman Ali Khalaf-von Jaffa (in German).

- Asiatic Cheetah Project - Felidae Conservation Fund, USA

- [2]

- Iran Department of Environment

- Video of hunting with Cheetahs in India

- Video on Youtube: Movie 'Cheetahs in Iran; the last stronghold of the Asiatic cheetah. Uploaded by kohvasang on Oct 31, 2011. this movie shows how they find the cheetahs in desert of iran. A video report which shows how Iranians and an international team cooperate to save scattered Cheetahs in Iran.

- Video on Youtube: Extinctions : Discover the endangered Asiatic cheetah. Uploaded by EXTINCTIONStv on Apr 29, 2010. Mohammad Farhadinia is the co-Founder of the Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), and Vice-President of Conservation of Asiatic Cheetah Project, whose goal is to study, and preserve the endangered Asiatic cheetah. Today, only few of them remain when they used to thrive in the Iranian plains just a hundred years ago.