Macular degeneration

| Macular degeneration | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

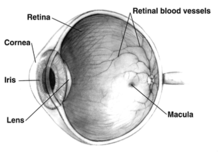

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a medical condition which usually affects older adults and results in a loss of vision in the center of the visual field (the macula) because of damage to the retina. It occurs in "dry" and "wet" forms. It is a major cause of blindness and visual impairment in older adults (>50 years). Macular degeneration can make it difficult or impossible to read or recognize faces, although enough peripheral vision remains to allow other activities of daily life.

Starting from the inside of the eye and going towards the back, the three main layers at the back of the eye are the retina, which contains the nerves; the choroid, which contains the blood supply; and the sclera, which is the white of the eye.

The macula is the central area of the retina, which provides the most detailed central vision.

In the dry (nonexudative) form, cellular debris called drusen accumulates between the retina and the choroid, and the retina can become detached. In the wet (exudative) form, which is more severe, blood vessels grow up from the choroid behind the retina, and the retina can also become detached. It can be treated with laser coagulation, and with medication that stops and sometimes reverses the growth of blood vessels.[1][2]

Although some macular dystrophies affecting younger individuals are sometimes referred to as macular degeneration, the term generally refers to age-related macular degeneration (AMD or ARMD).

Age-related macular degeneration begins with characteristic yellow deposits (drusen) in the macula, between the retinal pigment epithelium and the underlying choroid. Most people with these early changes (referred to as age-related maculopathy) have good vision. People with drusen can go on to develop advanced AMD. The risk is higher when the drusen are large and numerous and associated with disturbance in the pigmented cell layer under the macula. Large and soft drusen are related to elevated cholesterol deposits and may respond to cholesterol-lowering agents.

Dry AMD

Central geographic atrophy, the "dry" form of advanced AMD, results from atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelial layer below the retina, which causes vision loss through loss of photoreceptors (rods and cones) in the central part of the eye. No medical or surgical treatment is available for this condition; however, vitamin supplements with high doses of antioxidants, lutein and zeaxanthin, have been suggested by the National Eye Institute and others to slow the progression of dry macular degeneration and, in some patients, improve visual acuity.[3] However, recent advancements within the field of stem cell research in the United States have led to the first human embryonic stem cell trial for dry AMD, which reports positive results.[4]

Higher beta-carotene intake was associated with an increased risk of AMD.[3]

Wet AMD

Neovascular or exudative AMD, the "wet" form of advanced AMD, causes vision loss due to abnormal blood vessel growth (choroidal neovascularization) in the choriocapillaris, through Bruch's membrane, ultimately leading to blood and protein leakage below the macula. Bleeding, leaking, and scarring from these blood vessels eventually cause irreversible damage to the photoreceptors and rapid vision loss if left untreated.

Only about 10% of patients suffering from macular degeneration have the wet type.[5]

Macular degeneration is not painful, which may allow it to go unnoticed for some time.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of macular degeneration include:

- Drusen

- Pigmentary alterations

- Exudative changes: hemorrhages in the eye, hard exudates, subretinal/sub-RPE/intraretinal fluid

- Atrophy: incipient and geographic

- Visual acuity drastically decreasing (two levels or more), e.g.: 20/20 to 20/80.

- Preferential hyperacuity perimetry changes (for wet AMD) [7][8]

- Blurred vision: Those with nonexudative macular degeneration may be asymptomatic or notice a gradual loss of central vision, whereas those with exudative macular degeneration often notice a rapid onset of vision loss.

- Central scotomas (shadows or missing areas of vision)

- Distorted vision in the form of metamorphopsia, in which a grid of straight lines appears wavy and parts of the grid may appear blank: Patients often first notice this when looking at miniblinds in their home.

- Trouble discerning colors, specifically dark ones from dark ones and light ones from light ones

- Slow recovery of visual function after exposure to bright light

- A loss in contrast sensitivity

Macular degeneration by itself will not lead to total blindness. For that matter, only a very small number of people with visual impairment are totally blind. In almost all cases, some vision remains. Other complicating conditions may possibly lead to such an acute condition (severe stroke or trauma, untreated glaucoma, etc.), but few macular degeneration patients experience total visual loss.[9] The area of the macula comprises only about 2.1% of the retina, and the remaining 97.9% (the peripheral field) remains unaffected by the disease. Interestingly, even though the macula provides such a small fraction of the visual field, almost half of the visual cortex is devoted to processing macular information.[10]

The loss of central vision profoundly affects visual functioning. It is quite difficult, for example, to read without central vision. Pictures that attempt to depict the central visual loss of macular degeneration with a black spot do not really do justice to the devastating nature of the visual loss. This can be demonstrated by printing letters six inches high on a piece of paper and attempting to identify them while looking straight ahead and holding the paper slightly to the side. Most people find this difficult to do.

There is a loss of contrast sensitivity, so that contours, shadows, and color vision are less vivid. The loss in contrast sensitivity can be quickly and easily measured by a contrast sensitivity test performed either at home or by an eye specialist.

Similar symptoms with a very different etiology and different treatment can be caused by epiretinal membrane or macular pucker or leaking blood vessels in the eye.

Causes and risk factors

- Aging: Approximately 10% of patients 66 to 74 years of age will have findings of macular degeneration. The prevalence increases to 30% in patients 75 to 85 years of age.[12]

- Family history: The lifetime risk of developing late-stage macular degeneration is 50% for people who have a relative with macular degeneration, versus 12% for people who do not have relatives with macular degeneration.[12] Researchers from the University of Southampton reported they had discovered six mutations of the gene SERPING1 that are associated with AMD. Mutations in this gene can also cause hereditary angioedema.[13]

- Macular degeneration gene: The genes for the complement system proteins factor H (CFH), factor B (CFB) and factor 3 (C3) are strongly associated with a person's risk for developing AMD. CFH is involved in inhibiting the inflammatory response mediated via C3b (and the alternative pathway of complement) both by acting as a cofactor for cleavage of C3b to its inactive form, C3bi, and by weakening the active complex that forms between C3b and factor B. C-reactive protein and polyanionic surface markers such as glycosaminoglycans normally enhance the ability of factor H to inhibit complement. But the mutation in CFH (Tyr402His) reduces the affinity of CFH for CRP and probably also alters the ability of factor H to recognise specific glycosaminoglycans. This change results in reduced ability of CFH to regulate complement on critical surfaces such as the specialised membrane at the back of the eye and leads to increased inflammatory response within the macula. In two 2006 studies, another gene that has implications for the disease, called HTRA1 (encoding a secreted serine protease), was identified.[14][15]

The mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) in humans is contained on a single circular chromosome, 16,569 basepairs around, and each mitochondrion contains five to 10 copies of the mitochondrial chromosome. Several essential genes in mtDNA are involved in replication and translation, along with some genes that are crucial for the machinery that converts metabolic energy into ATP. These include NADH dehydrogenase, cytochrome C oxidase, ubiquinol/cytochrome C oxidoreductase, and ATP synthase, as well as the genes for unique ribosomal RNA and transfer RNA particles that are required for translating these genes into proteins.

Specific diseases are associated with mutations in some of these genes. Below is one of the affected genes and the disease that arises from its mutation. - Mutation of the ATP synthase gene: Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a genetically linked dysfunction of the retina and is related to mutation of the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthase gene 615.1617.

- Stargardt's disease (juvenile macular degeneration, STGD) is an autosomal recessive retinal disorder characterized by a juvenile-onset macular dystrophy, alterations of the peripheral retina, and subretinal deposition of lipofuscin-like material. A gene encoding an ATP-binding cassette transporter was mapped to the 2-cM (centiMorgan) interval at 1p13-p21 previously shown by linkage analysis to harbor this gene. This gene, ABCR, is expressed exclusively and at high levels in the retina, in rod but not cone photoreceptors, as detected by in situ hybridization. Mutational analysis of ABCR in STGD families revealed a total of 19 different mutations including homozygous mutations in two families with consanguineous parentage. These data indicate that ABCR is the causal gene of STGD/FFM.[16]

- Drusen: CMSD studies indicate drusen are similar in molecular composition to plaques and deposits in other age-related diseases such as Alzheimer's disease and atherosclerosis. While there is a tendency for drusen to be blamed for the progressive loss of vision, drusen deposits can be present in the retina without vision loss. Some patients with large deposits of drusen have normal visual acuity. If normal retinal reception and image transmission are sometimes possible in a retina when high concentrations of drusen are present, then, even if drusen can be implicated in the loss of visual function, there must be at least one other factor that accounts for the loss of vision.

- Arg80Gly variant of the complement protein C3: Two independent studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine and Nature Genetics in 2007 showed a certain common mutation in the C3 gene, which is a central protein of the complement system, is strongly associated with the occurrence of AMD.[17][18] The authors of both papers consider their study to underscore the influence of the complement pathway in the pathogenesis of this disease.

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Cholesterol: Elevated cholesterol may increase the risk of AMD [19]

- Fat intake Consuming high amounts of certain fats likely contributes to AMD, while monounsaturated fats are potentially protective.[21] In particular, ω-3 fatty acids may decrease the risk of AMD.[22]

- Oxidative stress: Age-related accumulation of low-molecular-weight, phototoxic, pro-oxidant melanin oligomers within lysosomes in the retinal pigment epithelium may be partly responsible for decreasing the digestive rate of photoreceptor outer rod segments (POS) by the RPE. A decrease in the digestive rate of POS has been shown to be associated with lipofuscin formation - a classic sign associated with AMD.[23][24]

- Fibulin-5 mutation: Rare forms of the disease are caused by geneic defects in fibulin-5, in an autosomal dominant manner. In 2004, Stone et al. performed a screen on 402 AMD patients and revealed a statistically significant correlation between mutations in fibulin-5 and incidence of the disease. Furthermore, the point mutants were found in the calcium-binding sites of the cbEGF domains of the protein. There is no structural basis for the effects of the mutations.

- Race: Macular degeneration is more likely to be found in Caucasians than in people of African descent.[25][26]

- Exposure to sunlight, especially blue light: Evidence is conflicting as to whether exposure to sunlight contributes to the development of macular degeneration. A recent study on 446 subjects found it does not.[27] Other research, however, has shown high-energy visible light may contribute to AMD.[28][29][30]

- Smoking: Smoking tobacco increases the risk of AMD by two to three times that of someone who has never smoked, and may be the most important modifiable factor in its prevention. A review of previous studies found "the literature review confirmed a strong association between current smoking and AMD. ... Cigarette smoking is likely to have toxic effects on the retina."[31]

- Deletion of CFHR3 and CFHR1: Deletion of the complement factor H-related genes CFHR3 and CFHR1 protects against AMD.[32][33]

Genetic testing

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (June 2011) |

A practical application of AMD-associated markers is in the prediction of progression of AMD from early stages of the disease to neovascularization.[34][35]

Early work demonstrated a family of immune mediators was plentiful in drusen.[36] Complement factor H (CFH) is an important inhibitor of this inflammatory cascade, and a disease-associated polymorphism in the CFH gene strongly associates with AMD.[37][38][39][40][41] Thus an AMD pathophysiological model of chronic low grade complement activation and inflammation in the macula has been advanced.[42][43] Lending credibility to this has been the discovery of disease-associated genetic polymorphisms in other elements of the complement cascade including complement component 3 (C3).[44]

The role of retinal oxidative stress in the etiology of AMD by causing further inflammation of the macula is suggested by the enhanced rate of disease in smokers and those exposed to UV irradiation.[45][46][47] Mitochondria are a major source of oxygen free radicals that occur as a byproduct of energy metabolism. Mitochondrial gene polymorphisms, such as that in the MT-ND2 molecule, predicts wet AMD.[48][49]

A powerful predictor of AMD is found on chromosome 10q26 at LOC 387715. An insertion/deletion polymorphism at this site reduces expression of the ARMS2 gene though destabilization of its mRNA through deletion of the polyadenylation signal.[50][51] ARMS2 protein may localize to the mitochondria and participate in energy metabolism, though much remains to be discovered about its function.

Other gene markers of progression risk includes tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 (TIMP3), suggesting a role for intracellular matrix metabolism in AMD progression. Variations in cholesterol metabolising genes such as the hepatic lipase, cholesterol ester transferase, lipoprotein lipase and the ABC-binding cassette A1 correlate with disease progression. The early stigmata of disease, drusen, are rich in cholesterol, offering face validity to the results of genome-wide association studies.[52][53]

Diagnosis

Fluorescein angiography allows for the identification and localization of abnormal vascular processes. Optical coherence tomography is now used by most ophthalmologists in the diagnosis and the followup evaluation of the response to treatment by using either bevacizumab (Avastin) or ranibizumab (Lucentis), which are injected into the vitreous humor of the eye at various intervals.

Recently, structured illumination light microscopy, using a specially designed super resolution microscope setup has been used to resolve the fluorescent distribution of small autofluorescent structures (lipofuscin granulae) in retinal pigment epithelium tissue sections.[54]

Management

Drugs approved for some variety of macular degeneration include ranibizumab and aflibercept (for wet AMD).

Treatments for wet AMD

The proliferation of abnormal blood vessels in the retina is stimulated by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Antiangiogenics or anti-VEGF agents can cause regression of the abnormal blood vessels and improve vision when injected directly into the vitreous humor of the eye. The injections must be repeated monthly or bimonthly. Several antiangiogenic drugs have been approved for use in the eye by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and regulatory agencies in other countries.

The first major anti-VEGF agent was bevacizumab, which was approved for use in cancer. Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody. Genentech, the manufacturer, developed bevacizumab into a smaller molecule, ranibizumab, for use in the eye, and got FDA approval for use in wet AMD. The cost of ranibizumab is approximately £742 per treatment in the United Kingdom.[55] Bevacizumab is packaged and used for cancer in larger doses than the doses used in the eye. It can be administered in smaller doses in the eye, off label, at a cost of less than one-tenth that of ranibizumab per treatment in the United Kingdom.[55] This use is controversial, and eye infections have been reported as a result of dividing the doses.[citation needed]

In the UK, NICE issued guidelines[56] for the treatment of wet AMD in the NHS. NICE only approved use of ranibizumab for wet AMD in the NHS in England. NHS hospitals and Primary Care Trusts in England are required to follow NICE guidance.

Other antiangiogenic drugs are pegaptanib (Macugen)[citation needed], aflibercept (Eylea) for treatment of wet AMD,[57] and pegaptanib (Macugen) for neovascular AMD.[citation needed]

Photodynamic therapy has also been used to treat wet AMD.[58] The drug verteporfin is administered intravenously; light of the correct wavelength is then applied to the abnormal blood vessels. This activates the verteporfin and obliterates the vessels.

Nondrug interventions

Some evidence supports a reduction in the risk of AMD with increasing intake of two carotenoids, lutein and zeaxanthin.[59]

Consuming omega-3 fatty acids (docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid) has been correlated with a reduced progression of early AMD, and in conjunction with low glycemic index foods, with reduced progression of advanced AMD.[60]

A Cochrane Database Review of publications to 2012 found the use of vitamin and mineral supplements, alone or in combination, by the general population had no effect on AMD,[61] a finding echoed by another review.[62] A 2006 Cochrane Review of the effects of vitamins and minerals on the slowing of AMD found the positive results mainly came from a single large trial in the United States (the Age-Related Eye Disease Study), with funding from the eye care product company Bausch & Lomb, which also manufactured the supplements used in the study,[63] and questioned the generalization of the data to any other populations with different nutritional status. The review also questioned the possible harm of such supplements, given the increased risk of lung cancer in smokers with high intakes of beta-carotene, and the increased risk of heart failure in at-risk populations who consume high levels of vitamin E supplements.[64] A Cochrane database review published in March 2012 did not find sufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness and safety of statins for the prevention or delaying the progression of AMD.[65]

Biofeedback

A 2012 observational study by Pacella et al. found a significant improvement in both visual acuity and fixation treating patients suffering from age-related macular degeneration or macular myopic degeneration with biofeedback treatment through MP-1 microperimeter.[66][non-primary source needed]

Adaptive devices

Because peripheral vision is not affected, people with macular degeneration can learn to use their remaining vision to partially compensate.[67] Assistance and resources are available in many countries and every state in the U.S.[68] Classes for "independent living" are given and some technology can be obtained from a state department of rehabilitation.

Adaptive devices can help people read. These include magnifying glasses, special eyeglass lenses, computer screen readers, and TV systems that enlarge reading material.

Computer screen readers such as JAWS or Thunder work with standard Windows computers.

Video cameras can be fed into standard or special-purpose computer monitors, and the image can be zoomed in and magnified. These systems often include a movable table to move the written material.

Accessible publishing provides larger fonts for printed books, patterns to make tracking easier, audiobooks and DAISY books with both text and audio.

Amsler grid test

The Amsler grid test is one of the simplest and most effective methods for patients to monitor the health of their maculae. The Amsler grid is, in essence, a pattern of intersecting lines (identical to graph paper) with a black dot in the middle. The central black dot is used for fixation (a place for the eye to focus). With normal vision, all lines surrounding the black dot will look straight and evenly spaced, with no missing or odd-looking areas when fixating on the grid's central black dot. When disease is affecting the macula, as in macular degeneration, the lines can look bent, distorted and/or missing.[citation needed]

See also

- Macular Disease Society

- Cherry-red spot

- Fuchs spot

- Micropsia

- Adeno associated virus and gene therapy of the human retina

- AMD Alliance International

References

- ^ de Jong PT (2006). "Age-related macular degeneration". N Engl J Med. 355 (14): 1474–1485. doi:10.1056/NEJMra062326. PMID 17021323.

- ^ Ch. 25, Disorders of the Eye, Jonathan C. Horton, in Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 16th ed.

- ^ a b Tan JS, Wang JJ, Flood V, Rochtchina E, Smith W, Mitchell P. (February 2008). "Dietary antioxidants and the long-term incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Blue Mountain Eye Study". Ophthalmology. 115 (2): 334–41. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.083. PMID 17664009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lanza, R (25). "Embryonic stem cell trials for macular degeneration: a preliminary report". Lancet.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Eye Conditions: Macular Degeneration". lasiksurgerycost.net. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- ^ "Age Related Macular Degeneration". visionenhancers.co.uk.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Preferential Hyperacuity Perimetry (PHP) as an Adjunct Diagnostic Tool to Funduscopy in Age–related Macular Degeneration - Ophthalmology Technology Spotlight". Medcompare. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- ^ Roberts, DL (2006). "The First Year--Age Related Macular Degeneration". (Marlowe & Company): 100.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Roberts, DL (2006). "The First Year--Age Related Macular Degeneration". (Marlowe & Company): 20.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b AgingEye Times (2009-05-19). "Macular Degeneration types and risk factors". Agingeye.net. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- ^ Hirschler, Ben (2008-10-07). "Gene discovery may help hunt for blindness cure". Reuters. Retrieved 2008-10-07. [dead link]

- ^ Yang Z, Camp NJ, Sun H, Tong Z, Gibbs D, Cameron DJ, Chen H, Zhao Y, Pearson E; et al. (2006). "A variant of the HTRA1 gene increases susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration". Science. 314 (5801): 992–3. doi:10.1126/science.1133811. PMID 17053109.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dewan A, Liu M, Hartman S; et al. (2006). "HTRA1 Promoter Polymorphism in Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration". Science. 314 (5801): 989–92. doi:10.1126/science.1133807. PMID 17053108.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ""ABCR Gene and Age-Related Macular Degeneration " Science. 1998". Sciencemag.org. 1998-02-20. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- ^ Yates JR, Sepp T, Matharu BK, Khan JC, Thurlby DA, Shahid H, Clayton DG, Hayward C, Morgan J, Wright AF, Armbrecht AM, Dhillon B, Deary IJ, Redmond E, Bird AC, Moore AT (2007). "Complement C3 Variant and the Risk of Age-Related Macular Degeneration". N Engl J Med. 357 (6): 553–561. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072618. PMID 17634448.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maller JB, Fagerness JA, Reynolds RC, Neale BM, Daly MJ, Seddon JM (2007). "Variation in Complement Factor 3 is Associated with Risk of Age-Related Macular Degeneration". Nature Genetics. 39 (10): 1200–1201. doi:10.1038/ng2131. PMID 17767156.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cholesterol-enriched diet causes age-related macular degeneration-like pathology in rabbit retina". BMC Ophthalmol. 11 (22). 18. doi:10.1186/1471-2415-11-22. PMC 3170645. PMID 21851605.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Adams MK, Simpson JA, Aung KZ; et al. (1). "Abdominal obesity and age-related macular degeneration". Am J Epidemiol. 173 (11): 1246–55. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr005. PMID 21422060. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Parekh N, Voland RP, Moeller SM; et al. (2009). "Association between dietary fat intake and age-related macular degeneration in the Carotenoids in Age-Related Eye Disease Study (CAREDS): an ancillary study of the Women's Health Initiative". Arch Ophthalmol. 127 (11): 1483–93. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.130. PMC 3144752. PMID 19901214.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ John Paul SanGiovanni, ScD; Emily Y. Chew, MD; Traci E. Clemons, PhD; Matthew D. Davis, MD; Frederick L. Ferris III, MD; Gary R. Gensler, MS; Natalie Kurinij, PhD; Anne S. Lindblad, PhD; Roy C. Milton, PhD; Johanna M. Seddon, MD; and Robert D. Sperduto, MD (May 5, 2007). "The Relationship of Dietary Lipid Intake and Age-Related Macular Degeneration in a Case-Control Study". Archives of Ophthalmology.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Melanin aggregation and polymerization: possible implications in age related macular degeneration." Ophthalmic Research, 2005; volume 37: pages 136-141.

- ^ John Lacey, "Harvard Medical signs agreement with Merck to develop potential therapy for macular degeneration", 23-May-2006

- ^ Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group (2000). "Risk Factors Associated with Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Case-control Study in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study: Age-Related Eye Disease Study Report Number 3". Ophthalmology. 107 (12): 2224–32. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00409-7. PMC 1470467. PMID 11097601.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Clemons TE, Milton RC, Klein R, Seddon JM, Ferris FL (2005). "Risk Factors for the Incidence of Advanced Age-Related Macular Degeneration in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) AREDS Report No. 19". Ophthalmology. 112 (4): 533–9. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.10.047. PMC 1513667. PMID 15808240.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Khan, JC (2006). "Age related macular degeneration and sun exposure, iris colour, and skin sensitivity to sunlight". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 90 (1): 29–32. doi:10.1136/bjo.2005.073825. PMC 1856929. PMID 16361662.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Glazer-Hockstein, C (2006). "Could blue light-blocking lenses decrease the risk of age-related macular degeneration?". Retina. 26 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1097/00006982-200601000-00001. PMID 16395131.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Margrain, TH (2004). "Do blue light filters confer protection against age-related macular degeneration?". Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 23 (5): 523–31. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.05.001. PMID 15302349.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Roberts, D (2005). "Artificial Lighting and the Blue Light Hazard". Macular Degeneration Support Online Library. http://www.mdsupport.org/library/hazard.html#blue.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|volume=|month=ignored (help) - ^ Eye. "Smoking and age-related macular degeneration: a review of association". Nature.com. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- ^ Hughes, Anne E; Orr, Nick; Esfandiary, Hossein; Diaz-Torres, Martha; Goodship, Timothy; Chakravarthy, Usha (2006). "A common CFH haplotype, with deletion of CFHR1 and CFHR3, is associated with lower risk of age-related macular degeneration". Nature Genetics. 38 (10): 1173–1177. doi:10.1038/ng1890. PMID 16998489.

- ^ Fritsche, L. G.; Lauer, N.; Hartmann, A.; Stippa, S.; Keilhauer, C. N.; Oppermann, M.; Pandey, M. K.; Kohl, J.; Zipfel, P. F. (2010). "An imbalance of human complement regulatory proteins CFHR1, CFHR3 and factor H influences risk for age-related macular degeneration (AMD)". Human Molecular Genetics. 19 (23): 4694–4704. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq399. PMID 20843825.

- ^ Chen W, Stambolian D, Edwards AO, Branham KE, Othman M, Jakobsdottir J (2010). "Genetic variants near TIMP3 and high-density lipoprotein–associated loci influence susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107 (16): 7401–7406. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912702107. PMC 2867722. PMID 20385819.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Neale BM, Fagerness J, Reynolds R, Sobrin L, Parker M, Raychaudhuri S (2010). "Genome-wide association study of advanced age-related macular degeneration identifies a role of the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC)". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107 (16): 7395–7400. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912019107. PMC 2867697. PMID 20385826.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mullins RF, Russell SR, Anderson DH, Hageman GS (2000). "Drusen associated with aging and age-related macular degeneration contain proteins common to extracellular deposits associated with atherosclerosis, elastosis, amyloidosis, and dense deposit disease". FASEB J. 14 (7): 835–46. PMID 10783137.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hageman GS, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, Hancox LS, Taiber AJ, Hardisty LI (2005). "A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102 (20): 7227–32. doi:10.1073/pnas.0501536102. PMC 1088171. PMID 15870199.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chen LJ, Liu DT, Tam PO, Chan WM, Liu K, Chong KK (2006). "Association of complement factor H polymorphisms with exudative age-related macular degeneration". Mol. Vis. 12: 1536–42. PMID 17167412.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Despriet DD, Klaver CC, Witteman JC, Bergen AA, Kardys I, de Maat MP (2006). "Complement factor H polymorphism, complement activators, and risk of age-related macular degeneration". JAMA. 296 (3): 301–9. doi:10.1001/jama.296.3.301. PMID 16849663.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Li M, Tmaca-Sonmez P, Othman M, Branham KE, Khanna R, Wade MS (2006). "CFH haplotypes without the Y402H coding variant show strong association with susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration". Nature Genetics. 38 (9): 1049–54. doi:10.1038/ng1871. PMC 1941700. PMID 16936733.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Haines JL, Hauser MA, Schmidt S, Scott WK, Olson LM, Gallins P (2005). "Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration". Science. 308 (5720): 419–21. doi:10.1126/science.1110359. PMID 15761120.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rohrer B, Long Q, Coughlin B, Renner B, Huang Y, Kunchithapautham K (2010). "A targeted inhibitor of the complement alternative pathway reduces RPE injury and angiogenesis in models of age-related macular degeneration". Adv Exp Med Biol. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 703: 137–49. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-5635-4_10. ISBN 978-1-4419-5634-7. PMID 20711712.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kunchithapautham K, Rohrer B (2011). "Sublytic Membrane-Attack-Complex (MAC) Activation Alters Regulated Rather than Constitutive Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) Secretion in Retinal Pigment Epithelium Monolayers". J Biol Chem. 286 (27): 23717–23724. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.214593. PMC 3129152. PMID 21566137.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Yates JR, Sepp T, Matharu BK, Khan JC, Thurlby DA, Shahid H (2007). "Complement C3 variant and the risk of age-related macular degeneration". NEJM. 357 (6): 553–61. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072618. PMID 17634448.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ^ Thornton J, Edwards R, Mitchell P, Harrison RA, Buchan I, Kelly SP (2005). "Smoking and age-related macular degeneration: a review of association". Eye. 19 (9): 935–44. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6701978. PMID 16151432.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tomany SC, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein R, Klein BE, Knudtson MD (2004). "Sunlight and the 10-year incidence of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study". Arch Ophthalmol. 122 (5): 750–7. doi:10.1001/archopht.122.5.750. PMID 15136324.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Szaflik JP, Janik-Papis K, Synowiec E, Ksiazek D, Zaras M, Wozniak K (2009). "DNA damage and repair in age-related macular degeneration". Mutat Res. 669 (1–2): 167–176.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Udar N, Atilano SR, Memarzadeh M, Boyer D, Chwa M, Lu S (2009). "Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups Associated with Age-Related Macular Degeneration". Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 50 (6): 2966–74. doi:10.1167/iovs.08-2646. PMID 19151382.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Canter JA, Olson LM, Spencer K, Schnetz-Boutaud N, Anderson B, Hauser MA (2008). "Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism A4917G is independently associated with age-related macular degeneration". PLoS ONE. 3 (5): e2091.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fritsche LG, Loenhardt T, Janssen A, Fisher SA, Rivera A, Keilhauer CN (2008). "Age-related macular degeneration is associated with an unstable ARMS2 (LOC387715) mRNA DNA damage and repair in age-related macular degeneration". NatGenet. 40 (7): 892–896.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Linkage analysis for age-related macular degeneration supports a gene on chromosome 10q26". Mol Vis. 26 (10): 57–61. 2004.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Chen W, Stambolian D, Edwards AO, Branham KE, Othman M, Jakobsdottir J (2010). "Genetic variants near TIMP3 and high-density lipoprotein–associated loci influence susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107 (16): 7401–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912702107. PMC 2867722. PMID 20385819.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Neale BM, Fagerness J, Reynolds R, Sobrin L, Parker M, Raychaudhuri S (2010). "Genome-wide association study of advanced age-related macular degeneration identifies a role of the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC)". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107 (16): 7395–400. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912019107. PMC 2867697. PMID 20385826.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Best G, Amberger R, Baddeley D, Ach T, Dithmar S, Heintzmann R and Cremer C (2011). Structured illumination microscopy of autofluorescent aggregations in human tissue. Micron, 42, 330-335 doi:10.1016/j.micron.2010.06.016

- ^ a b Copley, Caroline; Hirschler, Ben (April 24, 2012), Potter, Mark (ed.), Novartis challenges UK Avastin use in eye disease, Reuters, retrieved April 29, 2012

- ^ NICE guidelines

- ^ FDA Approves Eylea for Macular Degeneration

- ^ "Clinical effectiveness and cost–utility of photodynamic therapy for wet age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and economic evaluation". Hta.ac.uk. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- ^ Carpentier S, Knaus M, Suh M (2009). "Associations between lutein, zeaxanthin, and age-related macular degeneration: An overview". Critical reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 49 (4): 313–326. doi:10.1080/10408390802066979. PMID 19234943.

Abstract doesn't include conclusion

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chiu CJ, Klein R, Milton RC, Gensler G, Taylor A (2009). "Does eating particular diets alter the risk of age-related macular degeneration in users of the Age-Related Eye Disease Study supplements?". Br J Ophthalmol. 93 (9): 1241–6. doi:10.1136/bjo.2008.143412. PMC 3033729. PMID 19508997.

Conclusions: The findings show an association of consuming a diet rich in DHA with a lower progression of early AMD. In addition to the AREDS supplement, a lower dGI with higher intakes of DHA and EPA was associated with a reduced progression to advanced AMD.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Evans JR, Lawrenson JG (2012). "Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for preventing age-related macular degeneration". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6: CD000253. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000253.pub3. PMID 22696317.

- ^ Evans J (2008). "Antioxidant supplements to prevent or slow down the progression of AMD: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Eye. 22 (6): 751–60. doi:10.1038/eye.2008.100. PMID 18425071.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ SanGiovanni, JP (2009-01-21). "Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS)". ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ Evans JR; Evans, Jennifer R (2006). Evans, Jennifer R (ed.). "Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD000254. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000254.pub2. PMID 16625532.

- ^ Gehlbach P, Li T, Hatef E (2012). Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group (ed.). "Statins for age-related macular degeneration". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3: CD006927. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006927.pub3. PMID 22419318.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pacella, E; Pacella, F; Mazzeo; Turchetti, P; Carlesimo, SC; Cerutti, F; Lenzi, T; De Paolis, G; Giorgi, D (November 2012). "Effectiveness of vision rehabilitation treatment through MP-1 microperimeter in patients with visual loss due to macular disease". Clin Ter: 163(6):e423–8. PMID 23306757.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|firs3t=ignored (help) - ^ "Low Vision Rehabilitation Delivery Model". Mdsupport.org. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- ^ "Agencies, Centers, Organizations, & Societies". Mdsupport.org. 2005-09-01. Retrieved 2011-01-11.