The Count of Monte Cristo

| |

| Author | Alexandre Dumas in collaboration with Auguste Maquet |

|---|---|

| Original title | Le Comte de Monte-Cristo |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Historical novel |

Publication date | 1844-1845 (serialised) |

| Publication place | France |

The Count of Monte Cristo (French: Le Comte de Monte-Cristo) is an adventure novel by French author Alexandre Dumas (père). Complete in 1844, it is one of the author's most popular works, along with The Three Musketeers. Like many of his novels, it is expanded from plot outlines suggested by his collaborating ghostwriter Auguste Maquet.[1]

The story takes place in France, Italy, islands in the Mediterranean, and in the Levant during the historical events of 1815–1838. It begins from just before the Hundred Days period (when Napoleon returned to power after his exile) and spans through to the reign of Louis-Philippe of France. The historical setting is a fundamental element of the book. An adventure story primarily concerned with themes of hope, justice, vengeance, mercy and forgiveness, it focuses on a man who is wrongfully imprisoned, escapes from jail, acquires a fortune and sets about getting revenge on those responsible for his imprisonment. However, his plans have devastating consequences for the innocent as well as the guilty.

The book is considered a literary classic today. According to Luc Sante, "The Count of Monte Cristo has become a fixture of Western civilization's literature, as inescapable and immediately identifiable as Mickey Mouse, Noah's flood, and the story of Little Red Riding Hood."[2]

Background to the plot

Dumas wrote[3] that the idea of revenge in The Count of Monte Cristo came from a story in a book compiled by Jacques Peuchet, a French police archivist, published in 1838 after the death of the author.[4] Dumas included this essay in one of the editions from 1846.[5] Peuchet told of a shoemaker, Pierre Picaud, living in Nîmes in 1807, who was engaged to marry a rich woman when three jealous friends falsely accused him of being a spy for England. Picaud was placed under a form of house arrest, in the Fenestrelle Fort where he served as a servant to a rich Italian cleric. When the man died, he left his fortune to Picaud whom he had begun to treat as a son. Picaud then spent years plotting his revenge on the three men who were responsible for his misfortune. He stabbed the first with a dagger on which were printed the words, "Number One", and then he poisoned the second. The third man's son he lured into crime and his daughter into prostitution, finally stabbing the man himself. This third man, named Loupian, had married Picaud's fiancée while Picaud was under arrest.

In another of the "True Stories" Peuchet describes a poisoning in a family. This story, also quoted in the Pleiade edition, has obviously served as model for the chapter of the murders inside the Villefort family. The introduction to the Pleiade edition mentions other sources from real life: the Abbé Faria existed and died in 1819 after a life with much resemblance to that of the Faria in the novel. As for Dantès, his fate is quite different from his model in Peuchet's book, since the latter is murdered by the "Caderousse" of the plot. But Dantès has "alter egos" in two other Dumas works; in "Pauline" from 1838, and more significantly in "Georges" from 1843, where a young man with black ancestry is preparing a revenge against white people who had humiliated him.

A chronology of The Count of Monte Cristo and Bonapartism

During the life of Thomas-Alexandre Dumas:

- 1793: Thomas-Alexandre Dumas is promoted to the rank of general in the army of the First French Republic.

- 1794: He disapproves of the revolutionary terror in Western France.

- 1795-97: He becomes famous and fights under Napoleon.

- 1802: Black officers are dismissed from the army. The Empire re-establishes slavery.

- 1802: Birth of his son, Alexandre Dumas père.

- 1806: Thomas-Alexandre Dumas dies, still bitter about the injustice of the Empire.

During the life of Alexandre Dumas:

- 1832: The only son of Napoleon I dies.

- 1836: Alexandre Dumas is famous as a writer by this time (age 34).

- 1836: First putsch by Louis Napoleon, aged 28, fails.

- 1840: A law is passed to bring the ashes of Napoleon I to France.

- 1840: Second putsch of Louis Napoleon. He is imprisoned for life and becomes known as the candidate for the imperial succession.

- 1841: Dumas lives in Florence and becomes acquainted with King Jérôme and his son, Napoléon.

- 1841-44: The story is conceived and written.

- 1844-46: The story is published in parts in a Parisian magazine.

- 1846: The novel is published in full and becomes a European bestseller.

- 1846: Louis Napoleon escapes from his prison.

- 1848: French Second Republic. Louis Napoleon is elected its first president but Dumas does not vote for him.

- 1857: Dumas publishes État civil du Comte de Monte-Cristo

Plot summary

Edmond Dantès

In 1815 Edmond Dantès, a young and successful merchant sailor recently who has just been granted the succession of his erstwhile captain Leclère, returns to Marseille to marry his fiancée Mercédès. Leclère, a supporter of the exiled Napoléon I, found himself dying at sea and charged Dantès to deliver two objects: a package to Marshall Bertrand (exiled with Napoleon Bonaparte on Elba), and a letter from Elba to an unknown man in Paris. On the eve of his wedding to Mercédès, Fernand (Mercédès' cousin and a rival for her affections) is given subtle advice by Dantès's colleague Danglars (who is jealous of his rapid rise to captain), to send an anonymous note accusing Dantès of being a Bonapartist traitor. Caderousse (Dantès's cowardly and selfish neighbor) is drunk while the two conspirators set the trap for Dantès, and while he objects to the idea of hurting Dantès, he stays quiet the next day as Dantès is arrested then sentenced even though his testimony could have stopped the entire scandal from happening. Villefort, the deputy crown prosecutor in Marseille, while initially sympathetic to Dantès, destroys the letter from Elba when he discovers that it is addressed to his own father, a Bonapartist. In order to silence Dantès, he condemns him without trial to life imprisonment.

After six years of imprisonment in the Château d'If, Dantès is on the verge of suicide when he befriends the Abbé Faria ("The Mad Priest"), a fellow prisoner who he hears trying to tunnel his way to freedom. Faria's calculations on his tunnel were off, and it ends up connecting the two prisoners' cells rather than leading to freedom. Over the course of the next eight years, Faria comes to give Dantès an extensive education in language, culture, and science. He also explains to Dantès how Danglars, Fernand, and Villefort would each have had their own reasons for wanting Dantès in prison. Knowing himself to be close to death, Faria tells Dantès the location of a treasure on the island of Monte Cristo. When Faria dies, Dantès takes his place in the burial sack, moving the corpse to his own bed through their tunnel. When the guards throw the sack into the sea, Dantès escapes and swims to a nearby island where he is rescued by a smuggling ship the next morning. After several months of working with the smugglers, the ship makes a stop at Monte Cristo. Dantès fakes an injury and persuades the smugglers to leave him temporarily on the island while they finish their trip without him. He then makes his way to the hiding place of the treasure. After recovering the treasure, he leaves the smuggling business, buys a yacht, and returns to Marseille, where he begins to find out what became of everyone from his previous life. He later purchases both the island of Monte Cristo and the title of Count from the Tuscan government.

Returning to Marseille, Dantès learns that his father died of starvation during his imprisonment, but before embarking on his efforts for revenge, he first helps several people who were kind to him before his imprisonment. Traveling as the Abbé Busoni, he meets Caderousse, now living in poverty, whose intervention might have saved Dantès from prison. Dantès learns that his other enemies have all become wealthy. He gives Caderousse a diamond that can be either a chance to redeem himself, or a trap that will lead to his ruin. Learning that his old employer Morrel is on the verge of bankruptcy, Dantès, in the guise of a senior clerk from a banking firm, buys all of Morrel's outstanding debts and gives Morrel an extension of three months to fulfill his obligations. At the end of the three months and with no way to repay his debts, Morrel is about to commit suicide when he learns that all of his debts have been mysteriously paid and that one of his lost ships has returned with a full cargo, secretly rebuilt and laden by Dantès. Dantès rejoices at the Morrel family's joy, then pledges to banish all warm sentiments from his heart and dedicate himself to vengeance.

The Count of Monte Cristo

Disguised as the rich Count of Monte Cristo, Dantès takes revenge on the three men responsible for his unjust imprisonment: Fernand, now Count de Morcerf and Mercédès' husband; Danglars, now a baron and a wealthy banker; and Villefort, now procureur du roi — all of whom now live in Paris. The Count appears first in Rome, where he becomes acquainted with the Baron Franz d'Épinay, and Viscount Albert de Morcerf, the son of Mercédès and Fernand. Dantès arranges for the young Morcerf to be captured by the bandit Luigi Vampa before rescuing him from Vampa's gang. The Count then moves to Paris, and with Albert de Morcerf's introduction, becomes the sensation of the city. Due to his knowledge and rhetorical power, everyone (even his enemies, who do not recognize him) find him charming and seek his friendship. The Count dazzles the crass Danglars with his seemingly endless wealth, eventually persuading him to extend him a credit of six million francs, and withdraws 900,000. Under the terms of the arrangement, the Count can demand access to the remainder at any time. The Count manipulates the bond market, through a false telegraph signal, and quickly destroys a large portion of Danglars' fortune. The rest of it begins to rapidly disappear through mysterious bankruptcies, suspensions of payment, and more bad luck in the Stock Exchange.

Villefort had once conducted an affair with Madame Danglars. She became pregnant and delivered the child in the house that the Count has now purchased. In a desperate attempt to cover up the affair, Villefort told Madame Danglars that the infant had been stillborn. Villefort then smothered the child, and thinking him to be dead, he tried to bury him secretly behind the house. While Villefort was burying the child, he was stabbed by Bertuccio (who had swore vengeance on him after Villefort refused to do anything about the murder of Bertuccio's brother). Bertuccio assumed Villefort was burying treasure. He dug it up, found the near dead child and brought him back to life. Bertuccio's sister-in-law brought the child up, giving him the name "Benedetto". Benedetto ends up falling into a very bad crowd and in the end murders the sister-in-law while trying to rob her. After that, Benedetto runs away. The Count learns of this story from Bertuccio, who later becomes his servant. He purchases the house and hosts a dinner party there, to which he invites, among others, Villefort and Madame Danglars. During the dinner, the Count announces that, while doing landscaping, he had unearthed a box containing the remains of an infant and had referred the matter to the authorities to investigate. This puzzles Villefort, who knew that the infant's box had been removed and so the Count's story could not be true, and also alarms him that perhaps he knows the secret of his past affair with Madame Danglars and may be taunting him.

Meanwhile, Benedetto has grown up to become a criminal and is sentenced to the galleys with Caderousse. After the two are freed by "Lord Wilmore", Benedetto is sponsored by the Count to take the identity of "Viscount Andrea Cavalcanti" and is introduced by him into Parisian society at the same dinner party, with neither Villefort nor Madame Danglars suspecting that Andrea is their presumed dead son. Andrea then ingratiates himself to Danglars who betroths his daughter Eugénie to Andrea after cancelling her engagement to Albert, son of Fernand. Meanwhile, Caderousse blackmails Andrea, threatening to reveal his past. Cornered by "Abbé Busoni" while attempting to rob the Count's house, Caderousse begs to be given another chance, but Dantès grimly remarks that he had done so twice and Caderousse did not change. He forces Caderousse to write a letter to Danglars exposing Cavalcanti as an impostor and allows Caderousse to leave the house. The moment Caderousse leaves the estate, he is stabbed in the back by Andrea. Caderousse manages to dictate and sign a deathbed statement identifying his killer, and the Count reveals his true identity to Caderousse moments before Caderousse dies.

Years before, Ali Pasha, the ruler of Janina, had been betrayed to the Turks by Fernand. After Ali's death, Fernand sold Ali's wife Vasiliki and his daughter Haydée into slavery. Haydée was found and bought by Dantès and becomes the Count's ward. The Count manipulates Danglars into researching the event, which is published in a newspaper. As a result, Fernand is brought to trial for his crimes. Haydée testifies against him, and Fernand is disgraced. Mercédès, still beautiful, is the only person to recognize the Count as Dantès. When Albert blames the Count for his father's downfall and publicly challenges him to a duel, Mercédès goes secretly to the Count and begs him to spare her son. During this interview, she learns the truth of his arrest and imprisonment. She later reveals the truth to Albert, which causes Albert to make a public apology to the Count. Albert and Mercédès disown Fernand, who is confronted with Dantès' true identity and commits suicide. The mother and son depart to build a new life free of disgrace. Albert enlists as a soldier and goes to Africa in order to rebuild his life and honour under a new name, and Mercédès begins a solitary life in Marseille.

Villefort's daughter by his late first wife, Valentine, stands to inherit the fortune of her grandfather (Noirtier) and of her mother's parents (the Saint-Mérans), while his second wife, Héloïse, seeks the fortune for her son Édouard. The Count is aware of Héloïse's intentions, and "innocently" introduces her to the technique of poison. Héloïse fatally poisons the Saint-Mérans, so that Valentine inherits their fortune. Valentine is disinherited by Noirtier in an attempt to prevent Valentine's impending marriage with Franz d'Épinay. The marriage is cancelled when d'Épinay learns that his father (believed assassinated by Bonapartists) was killed by Noirtier in a duel. Afterwards, Valentine is reinstated in Noirtier's will. After a failed attempt on Noirtier's life, which instead claims the life of Noirtier's servant Barrois, Héloïse then targets Valentine so that Édouard will finally get the fortune. However, Valentine is the prime suspect in her father's eyes in the deaths of the Saint-Mérans and Barrois. On learning that Morrel's son Maximilien is in love with Valentine, the Count saves her by making it appear as though Héloïse's plan to poison Valentine has succeeded and that Valentine is dead. Villefort learns from Noirtier that Héloïse is the real murderer and confronts her, giving her the choice of a public execution or committing suicide by her own poison.

Fleeing after Caderousse's letter exposes him, Andrea gets as far as Compiègne before he is arrested and returned to Paris, where Villefort prosecutes him. While in prison awaiting trial, Andrea is visited by Bertuccio who tells him the truth about his father. At his trial, Andrea reveals that he is Villefort's son and was rescued after Villefort buried him alive. A stunned Villefort admits his guilt and flees the court. He rushes home to stop his wife's suicide but is too late; she has poisoned her son as well. Dantès confronts Villefort, revealing his true identity, but this, combined with the shock of the trial's revelations and the death of his wife and son, drives Villefort insane. Dantès tries to resuscitate Édouard but fails, and despairs that his revenge has gone too far. It is only after he revisits his cell in the Château d'If that Dantès is reassured that his cause is just and his conscience is clear, that he can fulfil his plan while being able to forgive both his enemies and himself.

After the Count's manipulation of the bond market, Danglars is left with only a destroyed reputation and 5,000,000 francs he has been holding in deposit for hospitals. The Count demands this sum to fulfil their credit agreement, and Danglars embezzles the hospital fund. Abandoning his wife, Danglars flees to Italy with the Count's receipt and 50,000 francs in petty cash, hoping to live in Vienna in anonymous prosperity. While leaving Rome, he is kidnapped by the Count's agent Luigi Vampa and is imprisoned in the same way as Albert. Forced to pay exorbitant prices for food and nearly starved to death (as Dantès's father had been), Danglars eventually signs away all of his ill-gotten gains. Dantès anonymously returns the stolen money to the hospitals. Left emaciated, grey-haired and driven nearly mad by his ordeal, Danglars finally repents his crimes. Dantès forgives Danglars and allows him to leave with his freedom and his 50,000 francs.

Maximilien Morrel, believing Valentine to be dead, contemplates suicide after her funeral. Dantès reveals his true identity and explains that he rescued Morrel's father from bankruptcy, disgrace and suicide years earlier; he then tells Maximilien to reconsider his suicide. On the island of Monte Cristo one month later, Dantès presents Valentine to Maximilien and reveals the true sequence of events. Having found peace, Dantès leaves the newly reunited couple his fortune and departs for an unknown destination to find comfort and a new life with Haydée, who has declared her love for him. The reader is left with a final thought: "all human wisdom is contained in these two words, 'Wait and Hope".

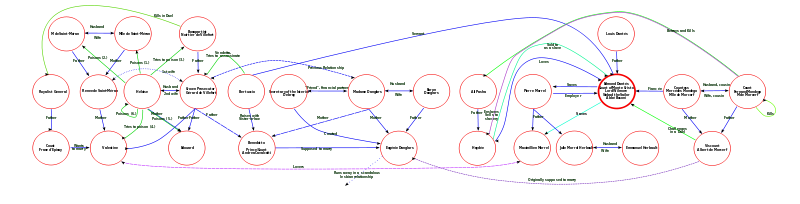

Characters

Edmond Dantès and his aliases

- Edmond Dantès (born 1796): A sailor with good prospects, engaged to Mercédès. After his transformation into the Count of Monte Cristo, he reveals his true name to his enemies as each revenge is completed. During the course of the novel, he falls in love with Haydee.

- The Count of Monte Cristo: The identity Dantès assumes when he emerges from prison and inherits his vast fortune. As a result, the Count of Monte Cristo is usually associated with a coldness and bitterness that comes from an existence based solely on revenge.

- English Chief Clerk of the banking firm Thomson and French

- Lord Wilmore: An Englishman, and the persona in which Dantès performs random acts of generosity.

- Sinbad the Sailor: The persona that Dantès assumes when he saves the Morrel family and assumes while mixing with smugglers and brigands.

- Abbé Busoni: The persona of an Italian priest with religious authority.

- Monsieur Zaccone: Dantès, in the guise of the Abbé Busoni, and again as Lord Wilmore, tells an investigator that this is the Count of Monte Cristo's true name.

- Number 34: The name given to him by the new governor of Château d'If. Finding it too tedious to learn Dantès real name, he was called by the number of his cell.

- The Maltese: The name he was known by after his rescue by smugglers from the island of Tiboulen.

Dantès' allies

- Abbé Faria: Italian priest and sage. Imprisoned in the Chateau d'If.

- Giovanni Bertuccio: The Count of Monte Cristo's steward and very loyal servant; foster father of Benedetto.

- Luigi Vampa: celebrated Italian bandit and fugitive.

- Peppino: Formerly a shepherd, he is later a bandit and full member of Vampa's gang.

- Haydée (also transliterated as Haidée): The daughter of Ali Pasha of Yanina (killed by Fernand Mondego), bought out of slavery by the Count. She later falls in love with Edmond.

- Ali: Monte Cristo's mute Nubian slave.

- Baptistin: Monte Cristo's valet-de-chambre.

- Jacopo: A poor smuggler who helps Dantès win his freedom. When Jacopo proves his selfless loyalty, Dantès rewards him with his own ship and crew.

Morcerf family

- Mercédès Mondego (née Herrera): Dantès's lover and fiancée at the beginning of the story. She later marries Fernand and has a son with him, Albert.

- Fernand Mondego: Count de Morcerf, Dantès's rival and cousin of Mercédès. Eventually marries her.

- Albert de Morcerf: Son of Mercédès and the Count de Morcerf, friend of Monte Cristo.

Danglars family

- Baron Danglars: Dantès' jealous junior officer at the beginning of the story, then later a wealthy banker.

- Madame Hermine Danglars (formerly Baroness Hermine de Nargonne née de Servieux): She had an affair with Gérard de Villefort. They had an illegitimate son, Benedetto.

- Eugénie Danglars: Daughter of Baron Danglars. She is free-spirited and aspires to become an independent artist.

Villefort family

- Gérard de Villefort: Royal prosecutor who imprisons Dantès, later becoming acquaintances as Dantès enacts his revenge.

- Renée de Villefort, née de Saint-Méran: Gérard de Villefort's first wife, mother of Valentine.

- The Marquis and Marquise de Saint-Méran: Renée's parents.

- Valentine de Villefort: The daughter of Gérard de Villefort and his first wife, Renée. In love with Maximilien Morrel. Engaged to Baron Franz d'Épinay. She is 19 years old with chestnut hair, dark blue eyes, and "long white hands"

- Monsieur Noirtier de Villefort: The father of Gérard de Villefort and grandfather of Valentine, Édouard (and, without knowing it, Benedetto). A committed anti-royalist.

- Héloïse de Villefort: The murderous second wife of Gérard de Villefort, mother of Edouard.

- Édouard de Villefort (Edward). The only legitimate son of Villefort.

- Benedetto: The illegitimate son of de Villefort and Baroness Hermine Danglars (Hermine de Nargonne), raised by Bertuccio and his sister-in-law, Assunta, in Rogliano. Becomes "Andrea Cavalcanti" in Paris.

Morrel family

- Pierre Morrel: Dantès's employer, owner of Morrel & Son.

- Maximilien Morrel: Son of Pierre Morrel, an army captain who becomes a friend of Dantès. In love with Valentine de Villefort.

- Julie Herbault: Daughter of Pierre Morrel, wife of Emmanuel Herbault.

- Emmanuel Herbault: an employee of Morrel & Son, who marries Julie Morrel and succeeds to the business.

Other characters

- Gaspard Caderousse: Originally a tailor and later the owner of an inn, he was a neighbour and friend of Dantès who fails to protect him at the beginning of the story and then turns to crime.

- Louis Dantès: Edmond Dantès' father, who dies of starvation while Edmond is in prison.

- Baron Franz d'Épinay: A friend of Albert de Morcerf, first fiancé of Valentine de Villefort.

- Lucien Debray: Secretary to the Minister of the Interior, a friend of Albert de Morcerf, and a lover and investment partner of Madame Danglars.

- Beauchamp: Journalist and friend of Albert de Morcerf.

- Raoul, Baron de Château-Renaud: Member of a noble family and friend of Albert de Morcerf.

- Louise d'Armilly: Eugénie Danglars' music instructor & her intimate friend.

- Monsieur de Boville: Originally an inspector of prisons, later a detective in the Paris force.

- Barrois: Old, trusted servant of Monsieur de Noirtier.

- Monsieur d'Avrigny: Family doctor treating the Villefort family.

- Major (also Marquis) Bartolomeo Cavalcanti: Old man who plays the role of Prince Andrea Cavalcanti's father.

- Ali Tebelen (Ali Tepelini in some versions): An Albanian nationalist leader, Pasha of Yanina, whom Fernand Mondego betrays, leading to Ali Pasha’s murder at the hands of the Turks and the seizure of his kingdom. His wife and daughter Haydée are sold into slavery.

Publication

The Count of Monte Cristo was originally published in the Journal des Débats in eighteen parts. Publication ran from August 28, 1844 to January 15, 1846. It was first published in Paris by Pétion in 18 volumes (1844-5).[6] Complete versions of the novel in the original French were published throughout the nineteenth century.

The most common English translation was originally published in 1846 by Chapman and Hall. Most unabridged English editions of the novel, including the Modern Library and Oxford World's Classics editions, use this translation, although Penguin Classics published a new translation by Robin Buss in 1996. Buss's translation updated the language, is more accessible to modern readers, and restored content that was modified in the 1846 translation because of Victorian English social restrictions (for example, references to Eugénie's lesbian traits and behaviour) to reflect Dumas' original version. Other English translations of the unabridged work exist, but are rarely seen in print and most borrow from the 1846 anonymous translation. Everyman's Library published a revised English translation by Peter Washington in 2009, with an introduction by Umberto Eco. This edition claims to have streamlined the 1846 translation by removing some repetitions and redundancies in Dumas' original text.

Alexandre Dumas wrote a set of three plays that collectively told the story of The Count of Monte Cristo: Monte Cristo (1848), Le Comte de Morcerf (1851), and Villefort (1851). The book itself went on to inspire the plot for a wide array of novels, from Lew Wallace's Ben-Hur (1880),[7] a Science Fiction retelling in Alfred Bester's The Stars My Destination[citation needed], to Stephen Fry's contemporary The Stars' Tennis Balls,[8]

Reception and legacy

The original work was published in serial form in the Journal des Débats in 1844. Carlos Javier Villafane Mercado described the effect in Europe:

- The effect of the serials, which held vast audiences enthralled ... is unlike any experience of reading we are likely to have known ourselves, maybe something like that of a particularly gripping television series. Day after day, at breakfast or at work or on the street, people talked of little else.[9]

George Saintsbury stated: "Monte Cristo is said to have been at its first appearance, and for some time subsequently, the most popular book in Europe. Perhaps no novel within a given number of years had so many readers and penetrated into so many different countries."[10] This popularity has extended into modern times as well. The book was "translated into virtually all modern languages and has never been out of print in most of them. There have been at least twenty-nine motion pictures based on it ... as well as several television series, and many movies [have] worked the name 'Monte Cristo' into their titles."[11] The title Monte Cristo lives on in a "famous gold mine, a line of luxury Cuban cigars, a sandwich, and any number of bars and casinos—it even lurks in the name of the street-corner hustle three-card monte."[12]

Modern Russian philologist Vadim Nikolayev determined The Count of Monte-Cristo as a megapolyphonic novel.[13]

Historical background

The success of Monte Cristo coincides with France's Second Empire. In the book, Dumas tells of the 1815 return of Napoleon I, and alludes to contemporary events when the governor at the Château d'If is promoted to a position at the castle of Ham.[Notes 1] The attitude of Dumas towards "bonapartisme" was conflicted. His father, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas,[Notes 2] a Haitian of mixed descent, became a successful general during the French Revolution. When new racial-discrimination laws were applied in 1802, the general was dismissed from the army and became profoundly bitter toward Napoleon. In 1840 the ashes of Napoleon I were brought to France and became an object of veneration in the church of Les Invalides, renewing popular patriotic support for the Bonaparte family.

In "Causeries" (1860), Dumas published a short paper, "État civil du Comte de Monte-Cristo", on the genesis of the Count of Monte-Cristo.[Notes 3] It appears that Dumas had close contacts with members of the Bonaparte family while living in Florence in 1841. In a small boat he sailed around the island of Monte-Cristo accompanied by a young prince, a cousin to Louis Bonaparte, who was to become emperor of France ten years later. During this trip he promised the prince that he would write a novel with the island's name in the title. At that time the future emperor was imprisoned at the citadel of Ham – a name that is mentioned in the novel. Dumas did visit him there,[14] although he does not mention it in "Etat civil". In 1840 Louis Napoleon was sentenced to life in prison, but escaped in disguise in 1846, while Dumas's novel was a great success. Just in the manner of Dantès, Louis Napoleon reappeared in Paris as a powerful and enigmatic man of the world. In 1848, however, Dumas did not vote for Louis Napoleon. The novel may have contributed, against the will of the writer, to the victory of the future Napoleon III.

Selected notable adaptations

Issue #3, published 1942.

Film and TV

- 1922: Monte Cristo, directed by Emmett J. Flynn

- 1934: The Count of Monte Cristo, directed by Rowland V. Lee

- 1940: The Son of Monte Cristo, directed by Rowland V. Lee

- 1942 El Conde de Montecristo, directed by Chano Urueta and starred by Arturo de Córdova

- 1946: The Return of Monte Christo, directed by Henry Levin

- 1950: The Prince of Revenge, Egyptian movie, directed by Henry Barkat

- 1954: El Conde de Montecristo, directed by León Klimovsky and starred by Jorge Mistral

- 1956: The Count of Monte Cristo, TV series based on further adventures of Edmond Dantès after the end of the novel

- 1958: Vanjikkottai Valiban, Tamil film adaptation

- 1961: Le comte de Monte Cristo, starring Louis Jourdan, directed by Claude Autant-Lara

- 1964: The Count of Monte Cristo, BBC television serial starring Alan Badel and Natasha Parry

- 1966: Il conte di Montecristo, RAI Italian television serial directed by Edmo Fenoglio. starring Andrea Giordana

- 1968: Sous le signe de Monte Cristo, French movie starring Paul Barge, Claude Jade and Anny Duperey, directed by André Hunebelle

- 1975: The Count of Monte Cristo, starring Richard Chamberlain, directed by David Greene

- 1977: The Great Vendetta, Hong Kong television serial starring Adam Cheng, in which the background of the story is changed to Southern China during the Republican Era

- 1984: La Dueña a 1984 Venezuelan telenovela with a female version of Edmond Dantès.

- 1988: The Prisoner of Castle If, Soviet miniseries starring Viktor Avilov (Count of Monte Cristo) and Aleksei Petrenko (Abbé Faria), with music and songs of Alexander Gradsky

Alexander Gradsky - Song of Monte Cristo on YouTube, Song of Freedom on YouTube, Song of Gold on YouTube, Song of Hope on YouTube, Farewell on YouTube (music and lyrics by Alexander Gradsky)

- Garfield and Friends episode "The Discount of Monte Cristo", a retelling of the story using the characters from U.S. Acres as the cast. Aloysius Pig, voiced by comedian Kevin Meaney, tries to cut the cost of the story, even though the characters are using their imaginations.

- 1998: The Count of Monte Cristo, television serial starring Gérard Depardieu

- 1999: Forever Mine, film starring Joseph Fiennes, Ray Liotta and Gretchen Mol, loosely but clearly based upon The Count of Monte Cristo, directed/written by Paul Schrader

- 2002: The Count of Monte Cristo, directed by Kevin Reynolds and starring Jim Caviezel and Guy Pearce

- 2004: Gankutsuou: The Count of Monte Cristo (巌窟王 Gankutsuoo, literally The King of the Cave), Japanese animation adaptation. Produced by Gonzo, directed by Mahiro Maeda

- 2006: Vingança, telenovela directed by Rodrigo Riccó and Paulo Rosa, SIC Portugal

- 2006: Montecristo, Argentine telenovela starring Pablo Echarri and Paola Krum

- 2010: Ezel, a Turkish television series billed as an adaptation of The Count of Monte Cristo.

- 2011: Revenge, a television series billed as an adaptation of The Count of Monte Cristo.

- David S. Goyer will direct an adaptation of The Count of Monte Cristo. [15]

Literary adaptations

- 1956: The Stars My Destination, Alfred Bester

- 2000: The Stars' Tennis Balls, Stephen Fry

- 2008: Master, an erotic version, Colette Gale

Sequels (books)

- 1853: A Mão do finado, Alfredo Hogan

- 1881: The Son of Monte Cristo, Jules Lermina

- 1869: The Countess of Monte Cristo, Jean Charles Du Boys, also 1934 and 1948

- 1946: The Wife of Monte Cristo

- 2012: The Sultan of Monte Cristo: First Sequel to the Count of Monte Cristo, The Holy Ghost Writer

Plays and musicals scripts

The story has been adapted into stage productions since the late 19th century. As early as 1875, James O'Neill, father of playwright Eugene, performed as the Count of Monte Cristo in a Chicago theatre, a role he would reprise over 6,000 times during his career. Following are some more recent stage adaptations.

- 2000: Monte Cristo by Karel Svoboda (music) and Zdenek Borovec (lyrics), Prague

- 2003: The Count of Monte Cristo (Граф Монте-Кристо) by Alexandr Tumencev and Tatyana Ziryanova

- 2006: Monte Cristo - The musical by Jon Smith and Leon Parris

- 2008: Monte-Cristo by Roman Ignatyev (composer) and Yuli Kim (lyrics), Moscow

- 2009: The Count of Monte Cristo by Frank Wildhorn

- 2009: The Count of Monte Cristo, by Ido Ricklin

- 2010: The Count of Monte Cristo, Rock Opera by Pete Sneddon

- 2012: The Count of Monte Cristo by Richard Bean, Royal National Theatre

- 2013: The Count of Monte Cristo produced by Cosmos Troupe of Takarazuka Revue

Audio adaptations

- 1938 - Orson Welles and The Mercury Theatre on the Air players (radio).

- 1939 - Orson Welles with Agnes Moorehead at The Campbell Playhouse (radio)

- 1939 - Robert Montgomery on the Lux Radio Theater (radio)

- 1947 - Carleton Young (radio series)

- 1960s - Paul Daneman for Tale Spinners For Children series (LP) UAC 11044

- 1961 - Louis Jourdan for Caedmon Records (LP)

- 1964 - Per Edström director (radio series in Sweden)[16]

- 1987 - Andrew Sachs on BBC Radio 4 (later BBC Radio 7 and BBC Radio 4 Extra)

- 2005 - John Lee for Blackstone Audiobooks

- 2012 - Iain Glen on BBC Radio 4 written by Sebastian Baczkiewicz and directed by Jeremy Mortimer and Sasha Yevtushenko, with Richard Johnson as Faria, Jane Lapotaire as the aged Haydee, Toby Jones as Danglars, Zubin Varla as Fernand, Paul Rhys as Villefort and Josette Simon as Mercedes.[17]

References

- ^ Schopp, Claude, Genius of Life, p. 325

- ^ Alexandre Dumas, The Count of Monte Cristo 2004, Barnes & Noble Books, New York. ISBN 978-1-59308-333-5. p. xxv (TCMC)

- ^ Etat civil du Comte de Monte-Cristo in Causeries, chapter IX (1857). See also the introduction of the Pléiade edition of Le comte de Monte-Cristo (1981)

- ^ Le Diamant et la Vengeance in Mémoires tirés des Archives de la Police de Paris, vol. 5, chapter LXXIV, p. 197

- ^ True Stories of Immortal Crimes, H. Ashton-Wolfe, 1931, E. P. Dutton & Co., pp. 16-17

- ^ David Coward (ed), Oxford's World Classics, Dumas, Alexandre, The Count of Monte Cristo, p. xxv

- ^ Lew Wallace (1906), Lew Wallace; an Autobiography P 936 ISBN 1-142-04820-9

- ^ Fry says The Stars' Tennis Balls (2000) (entitled Revenge in the US, is "a straight steal, virtually identical in all but period and style to Alexandre Dumas' The Count of Monte Cristo"; most character names are anagrams or cryptic references from Dumas' work. See Fry, Stephen (2003) Revenge (Introduction) Random House Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 0-8129-6819-0

- ^ TCMC p. xxiv

- ^ TCMC p. 601

- ^ TCMC p. xxiv

- ^ TCMC pp. xxiv–xxv

- ^ Template:Ru iconShakespeare and Le Comte de Monte-Cristo | The electronic encyclopedia World of Shakespeare

- ^ Pierre Milza (2004) Napoléon III. Perrin.

- ^ [1]

- ^ http://hem.passagen.se/vogler/skadespelare/fridh.htm

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01p0680

Notes

- ^ On p. 140 of the Pléiade edition the governor at the Château d'If is promoted to a position at the castle of Ham, which is the castle where Louis Napoleon was imprisoned 1840-46.

- ^ Thomas Alexandre Dumas was also known as Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie.

- ^ "État civil du Comte de Monte-Cristo" is included in the Pléiade edition (Paris, 1981) as an "annexe".

Further reading

- Maurois, André (1957). The Titans, a three-generation biography of the Dumas. trans. by Gerard Hopkins. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers. OCLC 260126.

- Schopp, Claude (1988). Alexandre Dumas, Genius of Life. trans. by A. J. Koch. New York, Toronto: Franklin Watts. ISBN 0-531-15093-3.

- Salien, Jean-Marie. La subversion de l’orientalisme dans Le comte de Monte-Cristo d’Alexandre Dumas, Études françaises, vol. 36, n° 1, 2000, pp. 179–190

- Toesca, Catherine (2002). Les sept Monte-Cristo d'Alexandre Dumas. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose. ISBN 2-7068-1613-9.

- Lenotre, G. La conquête et le règne in Revue des Deux Mondes, Jan/Feb 1919

- Blaze de Bury, H. (1885). Alexandre Dumas : sa vie, son temps, son oeuvre

- Maccinelli, Clara; Animato, Carlo (1991). "Il Conte di Montecristo" : Favola alchemica e massonica vendetta, Edizioni Mediterranee. ISBN 88-272-0791-0

- Cécile Raynal, Promenade médico-pharmaceutique à travers l'œuvre d'Alexandre Dumas, in Revue d'histoire de la pharmacie, 2002, Volume 90, N. 333, pp. 111–146

External links

- Critical approach on The Count of Monte Cristo by Enrique Javier González Camacho in Gibralfaro, the journal of creative writing and humanities at the University of Malaga (in Spanish)

- The Count of Monte Cristo, full text with embedded audio at PublicLiterature.Org

- The Count of Monte Cristo, an audiobook by LibriVox, available at Internet Archive

- Tale Spinners for Children: The Count of Monte Cristo MP3 download

- Pierre Picaud: The "Real" Count

- "Count of Monte Cristo Paris Walking Tour" identifies locations from the novel in Paris mapped on Google Maps

- The Count of Monte Cristo at Open Library

- The Count of Monte Cristo on BBC Radio 7

- The Count of Monte Cristo on Shmoop.com