Prefrontal cortex

- "Prefrontal" redirects here. For the skull bone, see Prefrontal bone. For the reptile scales, see Prefrontal scale.

| Prefrontal cortex | |

|---|---|

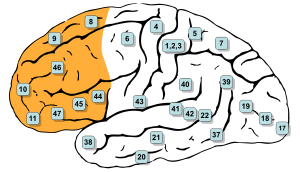

Brodmann areas of lateral surface. Per BrainInfo, parts of #8, #9, #10, #11, #44, #45, #46, and #47 are all in the prefrontal region. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Frontal lobe |

| Parts | Superior frontal gyrus Middle frontal gyrus Inferior frontal gyrus |

| Artery | Anterior cerebral Middle cerebral |

| Vein | Superior sagittal sinus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Cortex praefrontalis |

| MeSH | D017397 |

| NeuroNames | 2429 |

| NeuroLex ID | nlx_anat_090801, ilx_0109209 |

| FMA | 224850 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is the anterior part of the frontal lobes of the brain, lying in front of the motor and premotor areas.

This brain region has been implicated in planning complex cognitive behavior, personality expression, decision making, and moderating social behavior.[1] The basic activity of this brain region is considered to be orchestration of thoughts and actions in accordance with internal goals.[2]

The most typical psychological term for functions carried out by the prefrontal cortex area is executive function. Executive function relates to abilities to differentiate among conflicting thoughts, determine good and bad, better and best, same and different, future consequences of current activities, working toward a defined goal, prediction of outcomes, expectation based on actions, and social "control" (the ability to suppress urges that, if not suppressed, could lead to socially unacceptable outcomes).

Many authors have indicated an integral link between a person's personality and the functions of the prefrontal cortex.[3]

Definition

There are three possible ways to define the prefrontal cortex:

- as the granular frontal cortex

- as the projection zone of the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus

- as that part of the frontal cortex whose electrical stimulation does not evoke movements

The prefrontal cortex has been defined based on cytoarchitectonics by the presence of a cortical granular layer IV. It is not entirely clear who first used this criterion. Many of the early cytoarchitectonic researchers restricted the use of the term prefrontal to a much smaller region of cortex including the gyrus rectus and the gyrus rostralis (Campbell, 1905; G. E. Smith, 1907; Brodmann, 1909; von Economo and Koskinas, 1925). In 1935, however, Jacobsen used the term prefrontal to distinguish granular prefrontal areas from agranular motor and premotor areas.[4] In terms of Brodmann areas, the prefrontal cortex traditionally includes areas 8, 9, 10, 11, 44, 45, 46, and 47 (to complicate matters, not all of these areas are strictly granular—44 is dysgranular, caudal 11 and orbital 47 are agranular[5]). The main problem with this definition is that it works well only in primates but not in nonprimates, as the latter lack a granular layer IV.[6]

To define the prefrontal cortex as the projection zone of the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus builds on the work of Rose and Woolsey[7] who showed that this nucleus projects to anterior and ventral parts of the brain in nonprimates. Rose and Woolsey however termed this projection zone "orbitofrontal." It seems to have been Akert, who in 1964 for the first time explicitly suggested that this criterion could be used to define homologues of the prefrontal cortex in primates and nonprimates.[8] This allowed the establishment of homologies despite the lack of a granular frontal cortex in nonprimates. The projection zone definition is still widely accepted today (e.g. Fuster[9]), although its usefulness has been questioned.[5][10] Modern tract tracing studies have shown that projections of the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus are not restricted to the granular frontal cortex in primates. As a result, it was suggested to define the prefrontal cortex as the region of cortex that has stronger reciprocal connections with the mediodorsal nucleus than with any other thalamic nucleus.[6] Uylings et al.[6] acknowledge, however, that even with the application of this criterion it might be rather difficult to unequivocally define the prefrontal cortex.

A third definition of the prefrontal cortex is the area of frontal cortex whose electrical stimulation does not lead to observable movements. For example, in 1890 David Ferrier[11] used the term in this sense. One complication with this definition is that the electrically "silent" frontal cortex includes both granular and non-granular areas.[5]

Etymology

The term "prefrontal" as describing a part of the brain appears to have been introduced by Richard Owen in 1868.[4] For him, the prefrontal area was restricted to the anterior-most part of the frontal lobe (approximately corresponding to the frontal pole). It has been hypothesized that his choice of the term was based on the prefrontal bone present in most amphibians and reptiles.[4]

Subdivisions

The table below shows different ways to subdivide the prefrontal cortex starting from Brodmann areas. Note that the term "dorsolateral" has been used to denote areas 8, 9, and 46 as well as areas 8, 9, 44, 45, 46, and lateral 47[citation needed] and several terms are given to areas 47, 11 and 10.

Interconnections

The prefrontal cortex is highly interconnected with much of the brain, including extensive connections with other cortical, subcortical and brain stem sites.[12] The dorsal prefrontal cortex is especially interconnected with brain regions involved with attention, cognition and action,[13] while the ventral prefrontal cortex interconnects with brain regions involved with emotion.[14] The prefrontal cortex also receives inputs from the brainstem arousal systems, and its function is particularly dependent on its neurochemical environment.[15] Thus, there is coordination between our state of arousal and our mental state.[16]

The medial prefrontal cortex has been implicated in the generation of slow-wave sleep (SWS), and prefrontal atrophy has been linked to decreases in SWS.[17] Prefrontal atrophy occurs naturally as individuals age, and it has been demonstrated that older adults experience impairments in memory consolidation as their medial prefrontal cortices degrade.[17] Significant atrophy can also occur as a result of neuroleptic or antipsychotic psychiatric medication.[18] In older adults, instead of being transferred and stored in the neocortex during SWS, memories start to remain in the hippocampus where they were encoded, as evidenced by increased hippocampal activation compared to younger adults during recall tasks when subjects learned word associations, slept, and then were asked to recall the learned words.[17]

Studies

Perhaps the seminal case in prefrontal cortex function is that of Phineas Gage, whose left frontal lobe was destroyed when a large iron rod was driven through his head in an 1848 accident. The standard presentation (e.g.[19]) is that, although Gage retained normal memory, speech and motor skills, his personality changed radically: He became irritable, quick-tempered, and impatient—characteristics he did not previously display — so that friends described him as "no longer Gage"; and, whereas he had previously been a capable and efficient worker, afterward he was unable to complete tasks. However, careful analysis of primary evidence shows that descriptions of Gage's psychological changes are usually exaggerated when held against the description given by Gage's doctor, the most striking feature being that changes described years after Gage's death are far more dramatic than anything reported while he was alive.[20][21]

Subsequent studies on patients with prefrontal injuries have shown that the patients verbalized what the most appropriate social responses would be under certain circumstances. Yet, when actually performing, they instead pursued behavior aimed at immediate gratification, despite knowing the longer-term results would be self-defeating.

The interpretation of this data indicates that not only are skills of comparison and understanding of eventual outcomes harbored in the prefrontal cortex but the prefrontal cortex (when functioning correctly) controls the mental option to delay immediate gratification for a better or more rewarding longer-term gratification result. This ability to wait for a reward is one of the key pieces that define optimal executive function of the human brain.

There is much current research devoted to understanding the role of the prefrontal cortex in neurological disorders. Many disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and ADHD, have been related to dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex, and thus this area of the brain offers the potential for new treatments of these conditions.[citation needed] Clinical trials have begun on certain drugs that have been shown to improve prefrontal cortex function, including guanfacine, which acts through the alpha-2A adrenergic receptor. A downstream target of this drug, the HCN channel, is one of the most recent areas of exploration in prefrontal cortex pharmacology.[22]

Interference theory can be broken into three kinds: proactive, retroactive, and output.

- Proactive

- Proactive Interference was localized to the ventrolateral and left anterior prefrontal cortex using the “recent-probes” task.[23]

- Retroactive Interference

- Retroactive Interference has been localized to the left anterior ventral prefrontal cortex by magnetoencephalography studies investigating retroactive interference and working memory in elderly adults. The study found that adults 55–67 years of age showed less magnetic activity in their prefrontal cortices than the control group.[24]

- Output Interference

- Output Interference

Executive functions

It has been suggested that this article be merged with Attention versus memory in prefrontal cortex. (Discuss) Proposed since April 2013. |

The original studies of Fuster and of Goldman-Rakic emphasized the fundamental ability of the prefrontal cortex to represent information not currently in the environment, and the central role of this function in creating the "mental sketch pad". Goldman-Rakic spoke of how this representational knowledge was used to intelligently guide thought, action, and emotion, including the inhibition of inappropriate thoughts, distractions, actions, and feelings.[25] In this way, working memory can be seen as fundamental to attention and behavioral inhibition. Fuster speaks of how this prefrontal ability allows the wedding of past to future, allowing both cross-temporal and cross-modal associations in the creation of goal-directed, perception-action cycles.[26] This ability to represent underlies all other higher executive functions.

Shimamura proposed Dynamic Filtering Theory to describe the role of the prefrontal cortex in executive functions. The prefrontal cortex is presumed to act as a high-level gating or filtering mechanism that enhances goal-directed activations and inhibits irrelevant activations. This filtering mechanism enables executive control at various levels of processing, including selecting, maintaining, updating, and rerouting activations. It has also been used to explain emotional regulation.[27]

Miller and Cohen proposed an Integrative Theory of Prefrontal Cortex Function, that arises from the original work of Goldman-Rakic and Fuster. The two theorize that “cognitive control stems from the active maintenance of patterns of activity in the prefrontal cortex that represents goals and means to achieve them. They provide bias signals to other brain structures whose net effect is to guide the flow of activity along neural pathways that establish the proper mappings between inputs, internal states, and outputs needed to perform a given task”.[28] In essence, the two theorize that the prefrontal cortex guides the inputs and connections, which allows for cognitive control of our actions.

The prefrontal cortex is of significant importance when top-down processing is needed. Top-down processing by definition is when behavior is guided by internal states or intentions. According to the two, “The PFC is critical in situations when the mappings between sensory inputs, thoughts, and actions either are weakly established relative to other existing ones or are rapidly changing”.[28] An example of this can be portrayed in the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST). Subjects engaging in this task are instructed to sort cards according to the shape, color, or number of symbols appearing on them. The thought is that any given card can be associated with a number of actions and no single stimulus-response mapping will work. Human subjects with PFC damage are able to sort the card in the initial simple tasks, but unable to do so as the rules of classification change.

Miller and Cohen conclude that the implications of their theory can explain how much of a role the PFC has in guiding control of cognitive actions. In the researchers' own words, they claim that, “depending on their target of influence, representations in the PFC can function variously as attentional templates, rules, or goals by providing top-down bias signals to other parts of the brain that guide the flow of activity along the pathways needed to perform a task”.[28]

Experimental data indicate a role for the prefrontal cortex in mediating normal sleep physiology, dreaming and sleep-deprivation phenomena.[29]

When analyzing and thinking about attributes of other individuals, the medial prefrontal cortex is activated. However, it is not activated when contemplating about the characteristics of inanimate objects.[30] As of recent, researchers have used neuroimaging techniques to find that along with the basal ganglia, the prefrontal cortex is involved with learning exemplars, which is part of the exemplar theory, one of the three main ways our mind categorizes things. The exemplar theory states that we categorize judgements by comparing it to a similar past experience within our stored memories. [31]

Emotions

Prefrontal cortex does much of the work of emotion regulation through receiving signals from the amygdala and nucleus accumbens. This allows it to consider possible course of action and modify emotional responses once they are underway and fits the demands of the current social context.[32]

Damage to prefrontal cortex

Patients with damaged orbitfrontal cortex have problems in regulating emotional behavior as their reactions are inappropriate to social context. For example, showing a great deal of pride after teasing a stranger, when most people feel embarrassed at such an awkward social encounter. [33]

Emotional Responses

When people reappraise and shift attention of their emotional responses, the dorsal prefrontal cortex and left laterlized regions is involved to select what to attend and where to focus. Also, in the heat of an emotional response, a third person technique is studied. In this, you might look upon yourself from a third person prespective or as if you were an actor in a novel. This regulation engages the medial prefrontal cortex which is known to be involved in self representation.[34]

Disorders

In the last few decades, brain imaging systems have been used to determine brain region volumes and nerve linkages. Several studies have indicated that reduced volume and interconnections of the frontal lobes with other brain regions is observed in patients diagnosed with mental disorders and prescribed potent antipsychotics; those subjected to repeated stressors;[35] suicide victims;[36] those incarcerated; criminals; sociopaths; those affected by lead poisoning;[37] and drug addicts. It is believed that at least some of the human abilities to feel guilt or remorse, and to interpret reality, are dependent on a well-functioning prefrontal cortex.[38] It is also widely believed that the size and number of connections in the prefrontal cortex relates directly to sentience, as the prefrontal cortex in humans occupies a far larger percentage of the brain than any other animal. And it is theorized that, as the brain has tripled in size over 5 million years of human evolution,[39] the prefrontal cortex has increased in size sixfold.[40]

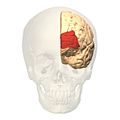

Image

These images of Brodmann area 10 give a clearer idea of the location of one particular sub-region of the prefrontal cortex.

-

Animation.

-

front view.

-

Lateral view.

-

Medial view.

See also

References

- ^ Yang Y, Raine A (2009). "Prefrontal structural and functional brain imaging findings in antisocial, violent, and psychopathic individuals: a meta-analysis". Psychiatry Res. 174 (2): 81–8. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.03.012. PMC 2784035. PMID 19833485.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Miller EK, Freedman DJ, Wallis JD (2002). "The prefrontal cortex: categories, concepts and cognition". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 357 (1424): 1123–36. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1099. PMC 1693009. PMID 12217179.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ DeYoung C. G., Hirsh J. B., Shane M. S., Papademetris X., Rajeevan N., Gray J. R. (2010). "Testing predictions from personality neuroscience". Psychological Science. 21 (6): 820–828. doi:10.1177/0956797610370159. PMC 3049165. PMID 20435951.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Finger, Stanley (1994). Origins of neuroscience: a history of explorations into brain function. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514694-8.

- ^ a b c Preuss TM (1995). "Do rats have prefrontal cortex? The Rose-Woolsey-Akert program reconsidered". The Journal of Cogntive Neuroscience. 7 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1162/jocn.1995.7.1.1.

- ^ a b c Uylings HB, Groenewegen HJ, Kolb B (2003). "Do rats have a prefrontal cortex?". Behavioural Brain Research. 146 (1–2): 3–17. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.028. PMID 14643455.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rose JE, Woolsey CN (1948). "The orbitofrontal cortex and its connections with the mediodorsal nucleus in rabbit, sheep and cat". Research Publications - Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Disease. 27 (1 vol.): 210–32. PMID 18106857.

- ^ Preuss TM, Goldman-Rakic PS (1991). "Myelo- and cytoarchitecture of the granular frontal cortex and surrounding regions in the strepsirhine primate Galago and the anthropoid primate Macaca". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 310 (4): 429–74. doi:10.1002/cne.903100402. PMID 1939732.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fuster, Joaquin M. (2008). The Prefrontal Cortex, Fourth Edition. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-373644-7.

- ^ Markowitsch HJ; Pritzel, M (1979). "The prefrontal cortex: Projection area of the thalamic mediodorsal nucleus?". Physiological Psychology. 7 (1): 1–6. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ^ Ferrier D (1890). "The Croonian lectures on cerebral localisation. Lecture II". The British Medical Journal. 1 (1537): 1349–1355. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.1537.1349. PMC 2207859. PMID 20753055.

- ^ Alvarez, J. A. & Emory, E., Julie A.; Emory, Eugene (2006). "Executive function and the frontal lobes: A meta-analytic review". Neuropsychology Review. 16 (1): 17–42. doi:10.1007/s11065-006-9002-x. PMID 16794878.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goldman-Rakic PS (1988). "Topography of cognition: parallel distributed networks in primate association cortex". Annu Rev Neurosci. 11: 137–56. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.001033. PMID 3284439.

- ^ Price JL (1999). "Prefrontal cortical networks related to visceral function and mood". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 877: 383–96. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09278.x. PMID 10415660.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Robbins TW, Arnsten AF (2009). "The neuropsychopharmacology of fronto-executive function: monoaminergic modulation". Annu Rev Neurosci. 32: 267–87. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135535. PMC 2863127. PMID 19555290.

- ^ Arnsten AF, Paspalas CD, Gamo NJ, Yang Y, Wang M (2010). "Dynamic Network Connectivity: A new form of neuroplasticity". Trends Cogn Sci. 14 (8): 365–75. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2010.05.003. PMC 2914830. PMID 20554470.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/nn.3324, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/nn.3324instead. - ^ Dorph-Petersen, KA (9). "The influence of chronic exposure to Antipsychotic Medications on Brain Size before and after Tissue Fixation: A comparison of Haloperidol and Olanzapine in Macaque Monkeys". Neuropsychopharmacology.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Antonio Damasio, Descartes' Error. Penguin Putman Pub., 1994

- ^ Malcolm Macmillan, An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage (MIT Press, 2000), pp.116-119, 307-333, esp. pp.11,333.

- ^ Macmillan, M. (2008). "Phineas Gage – Unravelling the myth" (PDF). The Psychologist. 21 (9). British Psychological Society: 828–831.

- ^ Wang, M.; et al. (2007). "Alpha2A-adrenoceptors strengthen working memory networks by inhibiting cAMP-HCN channel signaling in prefrontal cortex". Cell. 129 (2): 397–410. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.015. PMID 17448997.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Jonides J., Nee D.E. (2006). "Brain Mechanisms of Proactive Interference in Working Memory". Neuroscience. 139 (1): 181–193. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.042. PMID 16337090.

- ^ Solesio E., Lorenzo-López L., Campo P., López-Frutos J.M., Ruiz-Vargas J.M., Maestú F. (2009). "Retroactive interference in normal aging: A magnetoencephalography study". Neuroscience Letters. 456 (2): 85–88. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2009.03.087. PMID 19429139.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goldman-Rakic PS; Cools, A. R.; Srivastava, K. (1996). "The prefrontal landscape: implications of functional architecture for understanding human mentation and the central executive". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 351 (1346): 1445–53. doi:10.1098/rstb.1996.0129. JSTOR 3069191. PMID 8941956.

- ^ Fuster JM, Bodner M, Kroger JK (2000). "Cross-modal and cross-temporal association in neurons of frontal cortex". Nature. 405 (6784): 347–51. doi:10.1038/35012613. PMID 10830963.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shimamura, A. P. (2000). "The role of the prefrontal cortex in dynamic filtering" (PDF). Psychobiology. 28: 207–218. ISSN 0889-6313.

- ^ a b c Miller EK, Cohen JD (2001). "An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function". Annu Rev Neurosci. 24: 167–202. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. PMID 11283309.

- ^ Muzur, A.; Pace-Schott, E. F.; Hobson, J. A. (2002). The prefrontal cortex in sleep. ‘’Trends in Cognitive Sciences’’, 6(11), 475-481.

- ^ Mitchell, J.P, Heatherton, T.G., &Macrae, C.N. (2002). Distinct neural systems have subserve person and object knowledge. "proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 99, 15238-15243.

- ^ Schacter, Daniel L., Daniel Todd Gilbert, and Daniel M. Wegner. Psychology. 2nd ed, pages 364-366 New York, NY: Worth Publishers, 2011. Print.

- ^ Jenkins, Dacher Keltner, Keith Oatley, Jennifer M. Understanding emotions (3rd ed. ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. ISBN 9781118147436.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jenkins, Dacher Keltner, Keith Oatley, Jennifer M. Understanding emotions (3rd ed. ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. ISBN 9781118147436.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jenkins, Dacher Keltner, Keith Oatley, Jennifer M. Understanding emotions (3rd ed. ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. ISBN 9781118147436.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Liston C; et al. (2006). "Stress-induced alterations in prefrontal cortical dendritic morphology predict selective impairments in perceptual attentional set-shifting". J Neurosci. 26 (30): 7870–4. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1184-06.2006. PMID 16870732.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Rajkowska G (1997). "Morphometric methods for studying the prefrontal cortex in suicide victims and psychiatric patients". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 836: 253–68. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52364.x. PMID 9616803.

- ^ Cecil KM, Brubaker CJ, Adler CM, Dietrich KN, Altaye M, Egelhoff JC, Wessel S, Elangovan I, Hornung R; et al. (2008). Balmes, John (ed.). "Decreased brain volume in adults with childhood lead exposure". PLoS Med. 5 (5): e112. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050112. PMC 2689675. PMID 18507499.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Anderson SW; Bechara, A; Damasio, H; Tranel, D; Damasio, AR (1999). "Impairment of social and moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex". Nature Neuroscience. 2 (11): 1032–7. doi:10.1038/14833. PMID 10526345.

- ^ Schoenemann, P. Thomas (25). "Brain size does not predict general cognitive ability within families". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (9): 4932–4937. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4932. PMC 18335. PMID 10781101.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ted Cascio, Dr Ted Cascio. "Ph.D. in Hollywood Ph.D." Ted Cascio is co-editor of House & Psychology. Psychology Today. Retrieved 11/15/2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)