Cosmic ray

Cosmic rays are very high-energy particles, mainly originating outside the Solar System.[1] They may produce showers of secondary particles that penetrate and impact the Earth's atmosphere and sometimes even reach the surface. Composed primarily of high-energy protons and atomic nuclei, they are of mysterious origin. Data from the Fermi space telescope (2013)[2] have been interpreted as evidence that a significant fraction of primary cosmic rays originate from the supernovae of massive stars.[3] However, this is not thought to be their only source. Active galactic nuclei probably also produce cosmic rays.

The term ray is a historical accident, as cosmic rays were at first, and wrongly, thought to be mostly electromagnetic radiation. In modern common usage[4] high-energy particles with intrinsic mass are known as "cosmic" rays, and photons, which are quanta of electromagnetic radiation (and so have no intrinsic mass) are known by their common names, such as "gamma rays" or "X-rays", depending on their frequencies.

Cosmic rays attract great interest practically, due to the damage they inflict on microelectronics and life outside the protection of an atmosphere and magnetic field, and scientifically, because the energies of the most energetic ultra-high-energy cosmic rays (UHECRs) have been observed to approach 3 × 1020 eV,[5] about 40 million times the energy of particles accelerated by the Large Hadron Collider.[6] At 50 J,[7] the highest-energy ultra-high-energy cosmic rays have energies comparable to the kinetic energy of a 90-kilometre-per-hour (56 mph) baseball. As a result of these discoveries, there has been interest in investigating cosmic rays of even greater energies.[8] Most cosmic rays, however, do not have such extreme energies; the energy distribution of cosmic rays peaks at 0.3 gigaelectronvolts (4.8×10−11 J).[9]

Of primary cosmic rays, which originate outside of Earth's atmosphere, about 99% are the nuclei (stripped of their electron shells) of well-known atoms, and about 1% are solitary electrons (similar to beta particles). Of the nuclei, about 90% are simple protons, i. e. hydrogen nuclei; 9% are alpha particles, and 1% are the nuclei of heavier elements.[10] A very small fraction are stable particles of antimatter, such as positrons or antiprotons. The precise nature of this remaining fraction is an area of active research. An active search from Earth orbit for anti-alpha particles has failed to detect them.

History

After the discovery of radioactivity by Henri Becquerel in 1896, it was generally believed that atmospheric electricity, ionization of the air, was caused only by radiation from radioactive elements in the ground or the radioactive gases or isotopes of radon they produce. Measurements of ionization rates at increasing heights above the ground during the decade from 1900 to 1910 showed a decrease that could be explained as due to absorption of the ionizing radiation by the intervening air.

Discovery

In 1909 Theodor Wulf developed an electrometer, a device to measure the rate of ion production inside a hermetically sealed container, and used it to show higher levels of radiation at the top of the Eiffel Tower than at its base. However, his paper published in Physikalische Zeitschrift was not widely accepted. In 1911 Domenico Pacini observed simultaneous variations of the rate of ionization over a lake, over the sea, and at a depth of 3 meters from the surface. Pacini concluded from the decrease of radioactivity underwater that a certain part of the ionization must be due to sources other than the radioactivity of the Earth.[11]

Then, in 1912, Victor Hess carried three enhanced-accuracy Wulf electrometers[12] to an altitude of 5300 meters in a free balloon flight. He found the ionization rate increased approximately fourfold over the rate at ground level.[12] Hess also ruled out the Sun as the radiation's source by making a balloon ascent during a near-total eclipse. With the moon blocking much of the Sun's visible radiation, Hess still measured rising radiation at rising altitudes.[12] He concluded "The results of my observation are best explained by the assumption that a radiation of very great penetrating power enters our atmosphere from above." In 1913–1914, Werner Kolhörster confirmed Victor Hess' earlier results by measuring the increased ionization rate at an altitude of 9 km.

Hess received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1936 for his discovery.[13][14]

The Hess balloon flight took place on 7 August 1912. By sheer coincidence, exactly 100 years later on 7 August 2012, the Mars Science Laboratory rover used its Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) instrument to begin measuring the radiation levels on another planet for the first time. On 31 May 2013, NASA scientists reported that a possible manned mission to Mars may involve a great radiation risk based on the amount of energetic particle radiation detected by the RAD on the Mars Science Laboratory while traveling from the Earth to Mars in 2011-2012.[15][16][17]

Identification

In the 1920s the term "cosmic rays" was coined by Robert Millikan who made measurements of ionization due to cosmic rays from deep under water to high altitudes and around the globe. Millikan believed that his measurements proved that the primary cosmic rays were gamma rays, i.e., energetic photons. And he proposed a theory that they were produced in interstellar space as by-products of the fusion of hydrogen atoms into the heavier elements, and that secondary electrons were produced in the atmosphere by Compton scattering of gamma rays. But then, in 1927, J. Clay found evidence,[18] later confirmed in many experiments, of a variation of cosmic ray intensity with latitude, which indicated that the primary cosmic rays are deflected by the geomagnetic field and must therefore be charged particles, not photons. In 1929, Bothe and Kolhörster discovered charged cosmic-ray particles that could penetrate 4.1 cm of gold.[19] Charged particles of such high energy could not possibly be produced by photons from Millikan's proposed interstellar fusion process.

In 1930, Bruno Rossi predicted a difference between the intensities of cosmic rays arriving from the east and the west that depends upon the charge of the primary particles - the so-called "east-west effect."[20] Three independent experiments[21][22][23] found that the intensity is, in fact, greater from the west, proving that most primaries are positive. During the years from 1930 to 1945, a wide variety of investigations confirmed that the primary cosmic rays are mostly protons, and the secondary radiation produced in the atmosphere is primarily electrons, photons and muons. In 1948, observations with nuclear emulsions carried by balloons to near the top of the atmosphere showed that approximately 10% of the primaries are helium nuclei (alpha particles) and 1% are heavier nuclei of the elements such as carbon, iron, and lead.[24][24]

During a test of his equipment for measuring the east-west effect, Rossi observed that the rate of near-simultaneous discharges of two widely separated Geiger counters was larger than the expected accidental rate. In his report on the experiment, Rossi wrote "... it seems that once in a while the recording equipment is struck by very extensive showers of particles, which causes coincidences between the counters, even placed at large distances from one another."[23] In 1937 Pierre Auger, unaware of Rossi's earlier report, detected the same phenomenon and investigated it in some detail. He concluded that high-energy primary cosmic-ray particles interact with air nuclei high in the atmosphere, initiating a cascade of secondary interactions that ultimately yield a shower of electrons, and photons that reach ground level.

Soviet physicist Sergey Vernov was the first to use radiosondes to perform cosmic ray readings with an instrument carried to high altitude by a balloon. On 1 April 1935, he took measurements at heights up to 13.6 kilometers using a pair of Geiger counters in an anti-coincidence circuit to avoid counting secondary ray showers.[25][26]

Homi J. Bhabha derived an expression for the probability of scattering positrons by electrons, a process now known as Bhabha scattering. His classic paper, jointly with Walter Heitler, published in 1937 described how primary cosmic rays from space interact with the upper atmosphere to produce particles observed at the ground level. Bhabha and Heitler explained the cosmic ray shower formation by the cascade production of gamma rays and positive and negative electron pairs.

Energy distribution

Measurements of the energy and arrival directions of the ultra-high energy primary cosmic rays by the techniques of "density sampling" and "fast timing" of extensive air showers were first carried out in 1954 by members of the Rossi Cosmic Ray Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[27] The experiment employed eleven scintillation detectors arranged within a circle 460 meters in diameter on the grounds of the Agassiz Station of the Harvard College Observatory. From that work, and from many other experiments carried out all over the world, the energy spectrum of the primary cosmic rays is now known to extend beyond 1020 eV. A huge air shower experiment called the Auger Project is currently operated at a site on the pampas of Argentina by an international consortium of physicists, led by James Cronin, 1980 Nobel Prize in Physics of the University of Chicago and Alan Watson of the University of Leeds. Their aim is to explore the properties and arrival directions of the very highest-energy primary cosmic rays.[28] The results are expected to have important implications for particle physics and cosmology, due to a theoretical Greisen–Zatsepin–Kuzmin limit to the energies of cosmic rays from long distances (about 160 million light years) which occurs above 1020 eV because of interactions with the remnant photons from the big bang origin of the universe.

In November 2007, the Auger Project team announced some preliminary results. These showed that the directions of origin of the 27 highest-energy events were strongly correlated with the locations of active galactic nuclei (AGNs). The results support the theory that at the centre of each AGN is a large black hole exerting a magnetic field strong enough to accelerate a bare proton to energies of 1020 eV and higher.[29]

High-energy gamma rays (>50 MeV photons) were finally discovered in the primary cosmic radiation by an MIT experiment carried on the OSO-3 satellite in 1967.[30] Components of both galactic and extra-galactic origins were separately identified at intensities much less than 1% of the primary charged particles. Since then, numerous satellite gamma-ray observatories have mapped the gamma-ray sky. The most recent is the Fermi Observatory, which has produced a map showing a narrow band of gamma ray intensity produced in discrete and diffuse sources in our galaxy, and numerous point-like extra-galactic sources distributed over the celestial sphere.

Sources of cosmic rays

Early speculation on the sources of cosmic rays included a 1934 proposal by Baade and Zwicky suggesting cosmic rays originating from supernovae.[31] A 1948 proposal by Horace W. Babcock suggested that magnetic variable stars could be a source of cosmic rays.[32] Subsequently in 1951, Y. Sediko et al. identified the Crab Nebula as a source of cosmic rays.[33] Since then, a wide variety of potential sources for cosmic rays began to surface, including supernovae, active galactic nuclei, quasars, and gamma-ray bursts.[34]

Later experiments have helped to identify the sources of cosmic rays with greater certainty. In 2009, a paper presented at the International Cosmic Ray Conference (ICRC) by scientists at the Pierre Auger Observatory showed ultra-high energy cosmic rays (UHECRs) originating from a location in the sky very close to the radio galaxy Centaurus A, although the authors specifically stated that further investigation would be required to confirm Cen A as a source of cosmic rays.[35] However, no correlation was found between the incidence of gamma-ray bursts and cosmic rays, causing the authors to set a lower limit of 10−6 erg cm−2 on the flux of 1 GeV-1 TeV cosmic rays from gamma-ray bursts.[36]

In 2009, supernovae were said to have been "pinned down" as a source of cosmic rays, a discovery made by a group using data from the Very Large Telescope.[37] This analysis, however, was disputed in 2011 with data from PAMELA, which revealed that "spectral shapes of [hydrogen and helium nuclei] are different and cannot be described well by a single power law", suggesting a more complex process of cosmic ray formation.[38] In February 2013, though, research analyzing data from Fermi revealed through an observation of neutral pion decay that supernovae were indeed a source of cosmic rays, with each explosion producing roughly 3 × 1042 - 3 × 1043 J of cosmic rays.[2][3] However, supernovae do not produce all cosmic rays, and the proportion of cosmic rays that they do produce is a question which cannot be answered without further study.[39]

Types

Cosmic rays originate as primary cosmic rays, which are those originally produced in various astrophysical processes. Primary cosmic rays are composed primarily of protons and alpha particles (99%), with a small amount of heavier nuclei (~1%) and an extremely minute proportion of positrons and antiprotons.[10] Secondary cosmic rays, caused by a decay of primary cosmic rays as they impact an atmosphere, include neutrons, pions, positrons, and muons. Of these four, the latter three were first detected in cosmic rays.

Primary cosmic rays

Primary cosmic rays primarily originate from outside our Solar System and sometimes even the Milky Way. When they interact with Earth's atmosphere, they are converted to secondary particles. The mass ratio of helium to hydrogen nuclei, 28%, is similar to the primordial elemental abundance ratio of these elements, 24%.[40] The remaining fraction is made up of the other heavier nuclei that are nuclear synthesis end products, products of the Big Bang[citation needed], primarily lithium, beryllium, and boron. These light nuclei appear in cosmic rays in much greater abundance (~1%) than in the solar atmosphere, where they are only about 10−11 as abundant as helium.

This abundance difference is a result of the way secondary cosmic rays are formed. Carbon and oxygen nuclei collide with interstellar matter to form lithium, beryllium and boron in a process termed cosmic ray spallation. Spallation is also responsible for the abundances of scandium, titanium, vanadium, and manganese ions in cosmic rays produced by collisions of iron and nickel nuclei with interstellar matter.[41]

Primary cosmic ray antimatter

Satellite experiments have found evidence of positrons and a few antiprotons in primary cosmic rays, but these do not appear to be the products of large amounts of antimatter in the Big Bang, or indeed complex antimatter in the later Universe. Rather, they appear to consist of only these two types of elementary anti-particles, both newly made in energetic processes.

Preliminary results from the presently-operating Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS-02) on board the International Space Station show that positrons in the cosmic rays arrive with no directionality, and with energies that range from 10 GeV to 250 GeV, with the fraction of positrons to electrons increasing at higher energies. These results on interpretation have been suggested to be due to positron production in annihilation events of massive dark matter particles.

Antiprotons arrive at Earth with a characteristic energy maximum of 2 GeV, indicating their production in a fundamentally different process from cosmic ray protons, which on average have only one-sixth of the energy.[42]

There is no evidence of complex antimatter atomic nuclei, such as anti-helium nuclei (anti-alpha) particles, in cosmic rays. These are actively being searched for. A prototype of the AMS-02 designated AMS-01, was flown into space aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery on STS-91 in June 1998. By not detecting any antihelium at all, the AMS-01 established an upper limit of 1.1×10−6 for the antihelium to helium flux ratio.[43]

Secondary cosmic rays

When cosmic rays enter the Earth's atmosphere they collide with molecules, mainly oxygen and nitrogen. The interaction produce a cascade of lighter particles, a so-called air shower.[45] All of the produced particles stay within about one degree of the primary particle's path.

Typical particles produced in such collisions are neutrons and charged mesons such as positive or negative pions and kaons. Some of these subsequently decay into muons, which are able to reach the surface of the Earth, and even penetrate for some distance into shallow mines. The muons can be easily detected by many types of particle detectors, such as cloud chambers, bubble chambers or scintillation detectors. The observation of a secondary shower of particles in multiple detectors at the same time is an indication that all of the particles came from that event.

Cosmic rays impacting other planetary bodies in the Solar System are detected indirectly by observing high energy gamma ray emissions by gamma-ray telescope. These are distinguished from radioactive decay processes by their higher energies above about 10 MeV.

Cosmic-ray flux

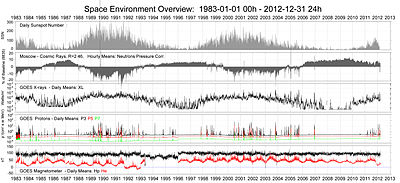

The flux of incoming cosmic rays at the upper atmosphere is dependent on the solar wind, the Earth's magnetic field, and the energy of the cosmic rays. At distances of ~94 AU from the Sun, the solar wind undergoes a transition, called the termination shock, from supersonic to subsonic speeds. The region between the termination shock and the heliopause acts as a barrier to cosmic rays, decreasing the flux at lower energies (≤ 1 GeV) by about 90%. However, the strength of the solar wind is not constant, and hence it has been observed that cosmic ray flux is correlated with solar activity.

In addition, the Earth's magnetic field acts to deflect cosmic rays from its surface, giving rise to the observation that the flux is apparently dependent on latitude, longitude, and azimuth angle. The magnetic field lines deflect the cosmic rays towards the poles, giving rise to the aurorae.

The combined effects of all of the factors mentioned contribute to the flux of cosmic rays at Earth's surface. For 1 GeV particles, the rate of arrival is about 10,000 per square meter per second. At 1 TeV the rate is 1 particle per square meter per second. At 10 PeV there are only a few particles per square meter per year. Particles above 10 EeV arrive only at a rate of about one particle per square kilometer per year, and above 100 EeV at a rate of about one particle per square kilometer per century.[47]

In the past, it was believed that the cosmic ray flux remained fairly constant over time. However, recent research suggests 1.5 to 2-fold millennium-timescale changes in the cosmic ray flux in the past forty thousand years.[48]

The magnitude of the energy of cosmic ray flux in interstellar space is very comparable to that of other deep space energies: cosmic ray energy density averages about one electron-volt per cubic centimeter of interstellar space, or ~1 eV/cm3, which is comparable to the energy density of visible starlight at 0.3 eV/cm3, the galactic magnetic field energy density (assumed 3 microgauss) which is ~0.25 eV/cm3, or the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation energy density at ~ 0.25 eV/cm3.[49]

Detection methods

There are several ground-based methods of detecting cosmic rays currently in use. The first detection method is called the air Cherenkov telescope, designed to detect low-energy (<200 GeV) cosmic rays by means of analyzing their Cherenkov radiation, which for cosmic rays are gamma rays emitted as they travel faster than the speed of light in their medium, the atmosphere.[50] While these telescopes are extremely good at distinguishing between background radiation and that of cosmic-ray origin, they can only function well on clear nights without the Moon shining, and have very small fields of view and are only active for a few percent of the time. Another Cherenkov telescope uses water as a medium through which particles pass and produce Cherenkov radiation to make them detectable.[51]

Extensive air shower (EAS) arrays, a second detection method, measure the charged particles which pass through them. EAS arrays measure much higher-energy cosmic rays than air Cherenkov telescopes, and can observe a broad area of the sky and can be active about 90% of the time. However, they are less able to segregate background effects from cosmic rays than can air Cherenkov telescopes. EAS arrays employ plastic scintillators in order to detect particles.

Another method was developed by Robert Fleischer, P. Buford Price, and Robert M. Walker for use in high-altitude balloons.[52] In this method, sheets of clear plastic, like 0.25 mm Lexan polycarbonate, are stacked together and exposed directly to cosmic rays in space or high altitude. The nuclear charge causes chemical bond breaking or ionization in the plastic. At the top of the plastic stack the ionization is less, due to the high cosmic ray speed. As the cosmic ray speed decreases due to deceleration in the stack, the ionization increases along the path. The resulting plastic sheets are "etched" or slowly dissolved in warm caustic sodium hydroxide solution, that removes the surface material at a slow, known rate. The caustic sodium hydroxide dissolves at a faster rate along the path of the ionized plastic. The net result is a conical etch pit in the plastic. The etch pits are measured under a high-power microscope (typically 1600x oil-immersion), and the etch rate is plotted as a function of the depth in the stacked plastic.

This technique yields a unique curve for each atomic nucleus from 1 to 92, allowing identification of both the charge and energy of the cosmic ray that traverses the plastic stack. The more extensive the ionization along the path, the higher the charge. In addition to its uses for cosmic-ray detection, the technique is also used to detect nuclei created as products of nuclear fission.

A fourth method involves the use of cloud chambers[53] to detect the secondary muons created when a pion decays. Cloud chambers in particular can be built from widely available materials and can be constructed even in a high-school laboratory. A fifth method, involving bubble chambers, can be used to detect cosmic ray particles.[54]

Effects

Changes in atmospheric chemistry

Cosmic rays ionize the nitrogen and oxygen molecules in the atmosphere, which leads to a number of chemical reactions. One of the reactions results in ozone depletion. Cosmic rays are also responsible for the continuous production of a number of unstable isotopes in the Earth's atmosphere, such as carbon-14, via the reaction:

- n + 14N → p + 14C

Cosmic rays kept the level of carbon-14[55] in the atmosphere roughly constant (70 tons) for at least the past 100,000 years, until the beginning of above-ground nuclear weapons testing in the early 1950s. This is an important fact used in radiocarbon dating used in archaeology.

- Reaction products of primary cosmic rays, radioisotope half-lifetime, and production reaction.[56]

Role in ambient radiation

Cosmic rays constitute a fraction of the annual radiation exposure of human beings on the Earth, averaging 0.39 mSv out of a total of 3 mSv per year (13% of total background) for the Earth's population. However, the background radiation from cosmic rays increases with altitude, from 0.3 mSv per year for sea-level areas to 1.0 mSv per year for higher-altitude cities, raising cosmic radiation exposure to a quarter of total background radiation exposure for populations of said cities. Airline crews flying long distance high-altitude routes can be exposed to 2.2 mSv of extra radiation each year due to cosmic rays, nearly doubling their total ionizing radiation exposure.

| Radiation | UNSCEAR[57][58] | Princeton[59] | Wa State[60] | MEXT[61] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Source | World average |

Typical range | USA | USA | Japan | Remark |

| Natural | Air | 1.26 | 0.2-10.0a | 2.29 | 2.00 | 0.40 | Primarily from Radon, (a)depends on indoor accumulation of radon gas. |

| Internal | 0.29 | 0.2-1.0b | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.40 | Mainly from radioisotopes in food (40K, 14C, etc.) (b)depends on diet. | |

| Terrestrial | 0.48 | 0.3-1.0c | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.40 | (c)Depends on soil composition and building material of structres. | |

| Cosmic | 0.39 | 0.3-1.0d | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.30 | (d)Generally increases with elevation. | |

| Subtotal | 2.40 | 1.0-13.0 | 2.95 | 2.95 | 1.50 | ||

| Artificial | Medical | 0.60 | 0.03-2.0 | 3.00 | 0.53 | 2.30 | |

| Fallout | 0.007 | 0 - 1+ | - | - | 0.01 | Peaked in 1963 with a spike in 1986; still high near nuclear test and accident sites. For the United States, fallout is incorporated into other categories. | |

| others | 0.0052 | 0-20 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.001 | Average annual occupational exposure is 0.7 mSv; mining workers have higher exposure. Populations near nuclear plants have an additional ~0.02 mSv of exposure annually. | |

| Subtotal | 0.6 | 0 to tens | 3.25 | 0.66 | 2.311 | ||

| Total | 3.00 | 0 to tens | 6.20 | 3.61 | 3.81 | ||

- Figures are for the time before the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Human-made values by UNCEAR are from the Japanese National Institute of Radiological Sciences, which summarized the UNCEAR data.

Effect on electronics

Cosmic rays have sufficient energy to alter the states of elements in electronic integrated circuits, causing transient errors to occur, such as corrupted data in electronic memory devices, or incorrect performance of CPUs, often referred to as "soft errors" (not to be confused with software errors caused by programming mistakes/bugs). This has been a problem in extremely high-altitude electronics, such as in satellites, but with transistors becoming smaller and smaller, this is becoming an increasing concern in ground-level electronics as well.[62] Studies by IBM in the 1990s suggest that computers typically experience about one cosmic-ray-induced error per 256 megabytes of RAM per month.[63] To alleviate this problem, the Intel Corporation has proposed a cosmic ray detector that could be integrated into future high-density microprocessors, allowing the processor to repeat the last command following a cosmic-ray event.[64]

Cosmic rays are suspected as a possible cause of an in-flight incident in 2008 where an Airbus A330 airliner of Qantas twice plunged hundreds of feet after an unexplained malfunction in its flight control system. Many passengers and crew members were injured, some seriously. After this incident, the accident investigators determined that the airliner's flight control system had received a data spike that could not be explained, and that all systems were in perfect working order. This has prompted a software upgrade to all A330 and A340 airliners, worldwide, so that any data spikes in this system are filtered out electronically.[65]

Significance to space travel

Galactic cosmic rays are one of the most important barriers standing in the way of plans for interplanetary travel by crewed spacecraft. Cosmic rays also pose a threat to electronics placed aboard outgoing probes. In 2010, a malfunction aboard the Voyager 2 space probe was credited to a single flipped bit, probably caused by a cosmic ray. Strategies such as physical or magnetic shielding for spacecraft have been considered in order to minimize the damage to electronics and human beings caused by cosmic rays.[66][67]

Role in lightning

Cosmic rays have been implicated in the triggering of electrical breakdown in lightning. It has been proposed that essentially all lightning is triggered through a relativistic process, "runaway breakdown", seeded by cosmic ray secondaries. Subsequent development of the lightning discharge then occurs through "conventional breakdown" mechanisms.[68]

Postulated role in climate change

A role of cosmic rays directly or via solar-induced modulations in climate change was suggested by Edward P. Ney in 1959[69] and by Robert E. Dickinson in 1975.[70] In recent years, the idea has been revived, most notably by Henrik Svensmark; the most recent IPCC study disputed the mechanism,[71] while the most comprehensive review of the topic to date states that while the amount of influence extraterrestrial factors have on Earth's climate is unclear, "evidence for the cosmic ray forcing is increasing as is the understanding of its physical principles."[72] While Svensmark suggests this may be the cause of the current upwards trend in average global temperatures,[73] his opinion is not widely accepted,[74] and is contrary to 97% of climate scientists who agree that factors other than GCR explain this trend.[75]

Suggested mechanisms

Henrik Svensmark has argued that because solar variations modulate the cosmic ray flux on Earth, they would consequently affect the rate of cloud formation and hence the climate. Cosmic rays have been experimentally determined capable of producing ultra-small aerosol particles;[77] however, these are orders of magnitude smaller than cloud condensation nuclei.

According to a report about the ongoing CERN CLOUD research project,[78] detecting any cosmic ray forcing is challenging, since on geological timescales changes in the Sun's magnetic activity, Earth's magnetic field, and the galactic environment must all be taken into account. Empirically, increased galactic cosmic ray (GCR) flux seem to be associated with a cooler climate and a weakening of monsoon rainfalls, or vice versa.[78] Claims have been made of identification of GCR climate signals in atmospheric parameters such as high-latitude precipitation and Svensmark's annual cloud cover variations.

Various proposals have been made for the mechanism by which cosmic rays might affect clouds, including ion mediated nucleation and indirect effects on current flow density in the global electric circuit, as suggested by Brian Tinsley[79] and Fangqun Yu.[80] Other studies refer to the formation of relatively highly charged aerosols and cloud droplets at cloud boundaries, with an indirect effect on ice particle formation and altering aerosol interaction with cloud droplets.[78] Kirkby (2009) reviews developments and describes further cloud nucleation mechanisms that appear energetically favorable and depend on GCRs.[81][82] However, the many processes which cause cosmic rays to seed clouds have yet to be definitely identified.[72]

Geochemical and astrophysical evidence

Nir Shaviv has argued that climate signals on geological time scales are attributable to changing positions of the galactic spiral arms of the Milky Way Galaxy, and that cosmic ray flux variability is the dominant "climate driver" over these time periods.[83] Nir Shaviv and Jan Veizer in 2003[76] argue, that in contrast to a carbon based scenario, the model and proxy based estimates of atmospheric CO2 levels especially for the early Phanerozoic (see diagrams) do not show correlation with the paleoclimate picture that emerged from geological criteria, while cosmic ray flux does.

The 2007 IPCC synthesis report, however, strongly attributes a major role in the ongoing global warming to human-produced gases such as carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and halocarbons, and has stated that models including natural forcings only (including aerosol forcings, which cosmic rays are considered by some to contribute to) would result in far less warming than has actually been observed or predicted in models including anthropogenic forcings.[84] The IPCC synthesis report only covers present and future changes in the Earth's climate, and does not mention paleoclimate or the influences which cosmic rays may have had on it.

A comprehensive study of different research institutes was published 2007 by Scherer et al.[72] The study combines geochemical evidence both on temperature, cosmic rays influence and as well astrophysical deliberations suggesting a major role in climate variability over different geological time scales. Proxy data of CRF influence comprise among others isotopic evidence in sediments on the Earth and as well changes in iron meteorites.

Research and experiments

There are a number of cosmic-ray research initiatives.

Ground-based

- Akeno Giant Air Shower Array

- CHICOS

- High Energy Stereoscopic System

- High Resolution Fly's Eye Cosmic Ray Detector

- MAGIC

- MARIACHI

- Pierre Auger Observatory

- Telescope Array Project

- Washington Large Area Time Coincidence Array

- CLOUD

- Spaceship Earth

- Milagro

- NMDB

- KASCADE

- GAMMA

- GRAPES-3

- HEGRA

- Chicago Air Shower Array

- IceCube

Satellite

Balloon-borne

See also

- Environmental radioactivity

- Forbush decrease

- Gilbert Jerome Perlow

- Extragalactic cosmic ray

- Solar energetic particle

- Track Imaging Cherenkov Experiment

Notes

- ^ Sharma (2008). Atomic And Nuclear Physics. Pearson Education India. p. 478. ISBN 978-81-317-1924-4.

- ^ a b Ackermann, M.; Ajello, M.; Allafort, A.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; Barbiellini, G.; Baring, M. G.; Bastieri, D.; Bechtol, K. (15 February 2013). "Detection of the Characteristic Pion-Decay Signature in Supernova Remnants". Science. 339 (6424). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 807–811. arXiv:1302.3307. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..807A. doi:10.1126/science.1231160. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ^ a b Ginger Pinholster (13 February 2013). "Evidence Shows that Cosmic Rays Come from Exploding Stars".

- ^ Dr. Eric Christian. "Are Cosmic Rays Electromagnetic radiation?". NASA. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ Nerlich, Steve (12 June 2011). "Astronomy Without A Telescope – Oh-My-God Particles". Universe Today. Universe Today. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ "Facts and figures". The LHC. European Organization for Nuclear Research. 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ Gaensler, Brian (2011). "Extreme speed". COSMOS (41).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

L. Anchordoqui, T. Paul, S. Reucroft, J. Swain (2003). "Ultrahigh Energy Cosmic Rays: The state of the art before the Auger Observatory". International Journal of Modern Physics A. 18 (13): 2229. arXiv:hep-ph/0206072. Bibcode:2003IJMPA..18.2229A. doi:10.1142/S0217751X03013879.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nave, Carl R. "Cosmic rays". HyperPhysics Concepts. Georgia State University. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ a b "What are cosmic rays?". NASA, Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^

D. Pacini (1912). "La radiazione penetrante alla superficie ed in seno alle acque". Il Nuovo Cimento, Series VI. 3: 93–100. doi:10.1007/BF02957440.

- Translated and commented in A. de Angelis (2010). "Penetrating Radiation at the Surface of and in Water". arXiv:1002.1810 [physics.hist-ph].

- ^ a b c "Nobel Prize in Physics 1936 – Presentation Speech". Nobelprize.org. 10 December 1936. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ V.F. Hess (1936). "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1936". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ V.F. Hess (1936). "Unsolved Problems in Physics: Tasks for the Immediate Future in Cosmic Ray Studies". Nobel Lectures. The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ a b Kerr, Richard (31 May 2013). "Radiation Will Make Astronauts' Trip to Mars Even Riskier". Science. 340 (6136): 1031. doi:10.1126/science.340.6136.1031. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ a b Zeitlin, C.; Hassler, D. M.; Cucinotta, F. A.; Ehresmann, B.; Wimmer-Schweingruber, R. F.; Brinza, D. E.; Kang, S.; Weigle, G.; Bottcher, S.; et al. (31 May 2013). "Measurements of Energetic Particle Radiation in Transit to Mars on the Mars Science Laboratory". Science. 340 (6136): 1080–1084. doi:10.1126/science.1235989. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b Chang, Kenneth (30 May 2013). "Data Point to Radiation Risk for Travelers to Mars". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ Clay, J. (1927). "Title unknown". Proceedings of the Section of Sciences, Koninklijke Akademie van Wetenschappen te Amsterdam. 30: 633.

- ^ Bothe, Walther and Werner Kolhörster (1929). "Das Wesen der Höhenstrahlung". Zeitschrift für Physik. 56 (11–12): 751–777. Bibcode:1929ZPhy...56..751B. doi:10.1007/BF01340137.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rossi, Bruno (1930). "On the Magnetic Deflection of Cosmic Rays". Physical Review. 36 (3): 606. Bibcode:1930PhRv...36..606R. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.36.606.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Johnson, Thomas H. (1933). "The Azimuthal Asymmetry of the Cosmic Radiation". Physical Review. 43 (10): 834–835. Bibcode:1933PhRv...43..834J. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.43.834.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Alvarez, Luis; Compton, Arthur Holly (1933). "A Positively Charged Component of Cosmic Rays". Physical Review. 43 (10): 835–836. Bibcode:1933PhRv...43..835A. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.43.835.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Rossi, Bruno (1934). "Directional Measurements on the Cosmic Rays Near the Geomagnetic Equator". Physical Review. 45 (3): 212–214. Bibcode:1934PhRv...45..212R. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.45.212.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "rossi-1934" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Freier, Phyllis; Lofgren, E.; Ney, E.; Oppenheimer, F.; Bradt, H.; Peters, B.; et al. (1948). "Evidence for Heavy Nuclei in the Primary Cosmic radiation". Physical Review. 74 (2): 213–217. Bibcode:1948PhRv...74..213F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.74.213.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "freier-1948" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^

J.L. DuBois, R.P. Multhauf, C.A. Ziegler (2002). The Invention and Development of the Radiosonde (PDF). Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology. Vol. 53. Smithsonian Institution Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ S. Vernoff (1935). "Radio-Transmission of Cosmic Ray Data from the Stratosphere". Nature. 135 (3426): 1072. Bibcode:1935Natur.135.1072V. doi:10.1038/1351072c0.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1103/PhysRev.122.637, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1103/PhysRev.122.637instead. - ^ Auger Project. "Auger Observatory: A New Astrophysics Facility Rises from the Pampa". Pierre Auger Observatory. Auger Project. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ^ Riesselmann, Kurt (2007). "On the trail of cosmic bullets" (PDF). Symmetry. 4 (8–9): 16–23.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kraushaar, W. L; et al. (1972). "Title unknown". The Astrophysical Journal. 177: 341. Bibcode:1972ApJ...177..341K. doi:10.1086/151713.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite jstor}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by jstor:86841, please use {{cite journal}} with

|jstor=86841instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1103/PhysRev.74.489, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1103/PhysRev.74.489instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1103/PhysRev.83.658.2, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1103/PhysRev.83.658.2instead. - ^ Gibb, Meredith (3 February 2010). "Cosmic Rays". Imagine the Universe. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Hague, J. D. (2009). "Correlation of the Highest Energy Cosmic Rays with Nearby Extragalactic Objects in Pierre Auger Observatory Data" (PDF). Proceedings of the 31st ICRC, Łódź 2009. International Cosmic Ray Conference. Łódź, Poland. pp. 6–9. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hague, J. D. (2009). "Correlation of the Highest Energy Cosmic Rays with Nearby Extragalactic Objects in Pierre Auger Observatory Data" (PDF). Proceedings of the 31st ICRC, Łódź 2009. International Cosmic Ray Conference. Łódź, Poland. pp. 36–39. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Moskowitz, Clara (25 June 2009). "Source of Cosmic Rays Pinned Down". Space.com. TechMediaNetwork. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.1199172, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.1199172instead. - ^ Jha, Alok (14 February 2013). "Cosmic ray mystery solved". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ Mewaldt, R.A., 2010. "Cosmic Rays". California Institute of Technology.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Koch, L.; Engelmann, J. J.; Goret, P.; Juliusson, E.; Petrou, N.; Rio, Y.; Soutoul, A.; Byrnak, B.; Lund, N.; Peters, B. (1981). "The relative abundances of the elements scandium to manganese in relativistic cosmic rays and the possible radioactive decay of manganese 54". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 102 (11): L9. Bibcode:1981A%26A...102L...9K.

{{cite journal}}: Check|bibcode=length (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moskalenko, I. V.; Strong, A. W.; Ormes, J. F; Potgieter, M. S. (2002). "Secondary antiprotons and propagation of cosmic rays in the Galaxy and heliosphere". The Astrophysical Journal. 565 (1): 280–296. arXiv:arXiv:astro-ph/0106567v2. Bibcode:2002ApJ...565..280M. doi:10.1086/324402.

{{cite journal}}: Check|arxiv=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ AMS Collaboration; Aguilar, M.; Alcaraz, J.; Allaby, J.; Alpat, B.; Ambrosi, G.; Anderhub, H.; Ao, L.; Arefiev, A. (2002). "The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS) on the International Space Station: Part I – results from the test flight on the space shuttle". Physics Reports. 366 (6): 331–405. Bibcode:2002PhR...366..331A. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(02)00013-3.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "EGRET Detection of Gamma Rays from the Moon". NASA/GSFC. 1 August 2005. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ Morison, Ian (2008). Introduction to Astronomy and Cosmology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-470-03333-3.

- ^ "Extreme Space Weather Events". National Geophysical Data Center.

- ^ "Pierre Auger Observatory". Auger.org. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^

D. Lal, A.J.T. Jull, D. Pollard, L. Vacher (2005). "Evidence for large century time-scale changes in solar activity in the past 32 Kyr, based on in-situ cosmogenic 14C in ice at Summit, Greenland". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 234 (3–4): 335–249. Bibcode:2005E&PSL.234..335L. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.02.011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Castellina, Antonella; Donato, Fiorenza (2012). Oswalt, T.D McLean, I.S.; Bond, H.E.; French, L.; Kalas, P.; Barstow, M.; Gilmore,G.F.; Keel, W. (ed.). Planets, Stars, and Stellar Systems (1 ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-90-481-8817-8. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Detection of Cosmic Rays". Milagro Gamma-Ray Observatory. Los Alamos National Laboratory. 3 April 2002. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "What are cosmic rays?" (PDF). Michigan State University National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^

R.L. Fleischer, P.B. Price, R.M. Walker (1975). Nuclear tracks in solids: Principles and applications. University of California Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cloud Chambers and Cosmic Rays: A Lesson Plan and Laboratory Activity for the High School Science Classroom" (PDF). Cornell University Laboratory for Elementary Particle Physics. 2006. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.24.917, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1103/PhysRevLett.24.917instead. - ^ Trumbore, Susan (2000). Noller, J. S., J. M. Sowers, and W. R. Lettis (ed.). Quaternary Geochronology: Methods and Applications. Washington, D.C.: American Geophysical Union. pp. 41–59. ISBN 0-87590-950-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ "Natürliche, durch kosmische Strahlung laufend erzeugte Radionuklide" (PDF). Retrieved 11 February 2010. Template:De icon

- ^ UNSCEAR "Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation" page 339 retrieved 2011-6-29

- ^ Japan NIRS UNSCEAR 2008 report page 8 retrieved 2011-6-29

- ^ Princeton.edu "Background radiation" retrieved 2011-6-29

- ^ Washington state Dept. of Health "Background radiation" retrieved 2011-6-29

- ^ Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan "Radiation in environment" retrieved 2011-6-29

- ^ IBM experiments in soft fails in computer electronics (1978–1994), from Terrestrial cosmic rays and soft errors, IBM Journal of Research and Development, Vol. 40, No. 1, 1996. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ Scientific American (21 July 2008). "Solar Storms: Fast Facts". Nature Publishing Group. Retrieved 8 December 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Intel plans to tackle cosmic ray threat, BBC News Online, 8 April 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ Cosmic rays may have hit Qantas plane off the coast of North West Australia, News.com.au, 18 November 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ Globus, Al (10 July 2002). "Appendix E: Mass Shielding". Space Settlements: A Design Study. NASA. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (24 January 2005). "Magnetic shielding for spacecraft". The Space Review. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ Runaway Breakdown and the Mysteries of Lightning, Physics Today, May 2005.

- ^ Ney, Edward P. (14 February 1959). "Cosmic Radiation and the Weather". Nature. 183 (4659): 451–452. Bibcode:1959Natur.183..451N. doi:10.1038/183451a0. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ Dickinson, Robert E. (1975). "Solar Variability and the Lower Atmosphere". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 56 (12): 1240–1248. Bibcode:1975BAMS...56.1240D. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1975)056<1240:SVATLA>2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Changes in Atmospheric Constituents and in Radiative Forcing IPCC Fourth Assessment Report Working Group I Report "The Physical Science Basis" 2007 [1]

- ^ a b c K. Scherer, H. Fichtner; et al. (December, 2006). "Interstellar-Terrestrial Relations: Variable Cosmic Environments, The Dynamic Heliosphere, and Their Imprints on Terrestrial Archives and Climate". Space Science Reviews. 127 (1–4). Springer Netherlands: 327–465. Bibcode:2006SSRv..127..327S. doi:10.1007/s11214-006-9126-6. ISSN 0038-6308.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Long, Marion (25 June 2007). "Sun's Shifts May Cause Global Warming". Discover. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ Plait, Phil (31 August 2011). "No, a new study does not show cosmic-rays are connected to global warming". Discover. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ Anderegg, William R. L. (21 June 2010). "Expert credibility in climate change". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (27): 12107–12109. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10712107A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003187107. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ a b N.J. Shaviv, J. Veizer; Veizer (2003). "Celestial driver of Phanerozoic climate?" (PDF). GSA Today. 7 (7): 4–10. Bibcode:2003EAEJA....13401S. doi:10.1130/1052-5173(2003)013<0004:CDOPC>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1052-5173.

- ^ Henrik Svensmark, Jens Olaf Pepke Pedersen, Nigel Marsh, Martin Enghoff and Ulrik Uggerhøj, "Experimental Evidence for the role of Ions in Particle Nucleation under Atmospheric Conditions", Proceedings of the Royal Society A, (Early Online Publishing), 2006.

- ^ a b c Kirkby, Jasper (2007). "Cosmic Rays and Climate". Surveys in Geophysics. 28 (5–6): 333–375. arXiv:0804.1938. Bibcode:2007SGeo...28..333K. doi:10.1007/s10712-008-9030-6. ISSN 1573-0956.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tinsley, Brian A. (2000). "Influence of Solar Wind on the Global Electric Circuit, and Inferred Effects on Cloud Microphysics, Temperature, and Dynamics in the Troposphere". Space Science Reviews. 94 (1–2): 231–258. doi:10.1023/A:1026775408875.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Yu, Fangqun (2002). "Altitude variations of cosmic ray induced production of aerosols: Implications for global cloudiness and climate". Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics. 107 (A7). doi:10.1029/2001JA000248'. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cosmic Rays and Climate Video Jasper Kirkby, CERN Colloquium, 4 June 2009

- ^ Cosmic Rays and Climate Presentation Jasper Kirkby, CERN Colloquium, 4 June 2009

- ^ [2], [3] sciencebits.com/CO2orSolar Science bit display of Nir Shaviv papers

- ^ Core Writing Team (17). Pachauri, R.K. and Reisinger, A. (ed.). Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. IPCC Plenary XXVII. Valencia, Spain: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. pp. 39–40. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

{{cite conference}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|conferenceurl=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

References

- R.G. Harrison and D.B. Stephenson, Detection of a galactic cosmic ray influence on clouds, Geophysical Research Abstracts, Vol. 8, 07661, 2006 SRef-ID: 1607-7962/gra/EGU06-A-07661

- C. D. Anderson and S. H. Neddermeyer, Cloud Chamber Observations of Cosmic Rays at 4300 Meters Elevation and Near Sea-Level, Phys. Rev 50, 263,(1936).

- M. Boezio et al., Measurement of the flux of atmospheric muons with the CAPRICE94 apparatus, Phys. Rev. D 62, 032007, (2000).

- R. Clay and B. Dawson, Cosmic Bullets, Allen & Unwin, 1997. ISBN 1-86448-204-4

- T. K. Gaisser, Cosmic Rays and Particle Physics, Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-521-32667-2

- P. K. F. Grieder, Cosmic Rays at Earth: Researcher's Reference Manual and Data Book, Elsevier, 2001. ISBN 0-444-50710-8

- A. M. Hillas, Cosmic Rays, Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1972 ISBN 0-08-016724-1

- J. Kremer et al., Measurement of Ground-Level Muons at Two Geomagnetic Locations, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 4241, (1999).

- S. H. Neddermeyer and C. D. Anderson, Note on the Nature of Cosmic-Ray Particles, Phys. Rev. 51, 844, (1937).

- M. D. Ngobeni and M. S. Potgieter, Cosmic ray anisotropies in the outer heliosphere, Advances in Space Research, 2007.

- M. D. Ngobeni, Aspects of the modulation of cosmic rays in the outer heliosphere, M.Sc Dissertation, Northwest University (Potchefstroom campus) South Africa 2006.

- D. Perkins, Particle Astrophysics, Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-850951-0

- C. E. Rolfs and S. R. William, Cauldrons in the Cosmos, The University of Chicago Press, 1988. ISBN 0-226-72456-5

- B. B. Rossi, Cosmic Rays, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1964.

- Martin Walt, Introduction to Geomagnetically Trapped Radiation, 1994. ISBN 0-521-43143-3

- M. Taylor and M. Molla, Towards a unified source-propagation model of cosmic rays, Pub. Astron. Soc. Pac. 424, 98 (2010).

- J. F. Ziegler, The Background In Detectors Caused By Sea Level Cosmic Rays, Nuclear Instruments and Methods 191, 419, (1981).

- TRACER Long Duration Balloon Project: the largest cosmic ray detector launched on balloons.

- Carlson, Per; De Angelis, Alessandro (2011). "Nationalism and internationalism in science: the case of the discovery of cosmic rays". European Physical Journal H. 35 (4): 309. arXiv:1012.5068. Bibcode:2010EPJH...35..309C. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2011-10033-6.

External links

- Aspera European network portal

- Animation about cosmic rays on astroparticle.org

- Helmholtz Alliance for Astroparticle Physics

- Particle Data Group review of Cosmic Rays by C. Amsler et al., Physics Letters B667, 1 (2008).

- Introduction to Cosmic Ray Showers by Konrad Bernlöhr.

- BBC news, Cosmic rays find uranium, 2003.

- BBC news, Rays to nab nuclear smugglers, 2005.

- BBC news, Physicists probe ancient pyramid (using cosmic rays), 2004.

- Shielding Space Travelers by Eugene Parker.

- Anomalous cosmic ray hydrogen spectra from Voyager 1 and 2

- Anomalous Cosmic Rays (From NASA's Cosmicopia)

- Review of Cosmic Rays

- "Who's Afraid of a Solar Flare? Solar activity can be surprisingly good for astronauts." 7 October 2005, at Science@NASA

- video of Muon detector in use at Smithsonian Air and Space Museum

- Dr. Lothar Frey "Cosmic rays and electronic devices" (YouTube Video) SpaceUp Stuttgart 2012

- Padilla, Antonio (Tony). "Where do Cosmic Rays come from?". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.