Mjölnir

In Norse mythology, Mjölnir (/ˈmjɒlnɪər/ or /ˈmjɒlnər/ MYOL-n(ee)r; also Mjǫlnir, Mjollnir, Mjölner or Mjølner) is the hammer of Thor, the Norse god of thunder. Mjölnir is depicted in Norse mythology as one of the most fearsome weapons, capable of leveling mountains.

In his account of Norse mythology Snorri Sturluson relates how the hammer was made by the dwarven brothers Sindri and Brokkr, and how its characteristically short handle was due to a mishap during its manufacture.

Name

Mjölnir is usually interpreted as meaning "That which smashes", derived from the verb mölva "To smash" (cognate with English meal, mill); comparable derivations from the same root meaning "hammer" are Slavic molot and Latin malleus (whence English mallet).

An alternative suggestion compares the name to Russian молния (molniya) and the Welsh word mellt, both words are taken as meaning "lightning". This second theory would make Mjölnir the weapon of the storm god identified with lightning, as in the lightning-bolt or vajra in other Indo-European mythologies.[1]

Norse mythology

Skáldskaparmál

An account of the creation of Mjölnir is found in Skáldskaparmál from Snorri's Edda: In this story, Loki bets his head with Sindri (or Eitri) and his brother Brokkr that they could never succeed in making items more beautiful than those of the Sons of Ivaldi (the dwarves who created other precious items for the gods: Odin's spear Gungnir, and Freyr's foldable boat Skíðblaðnir).

Sindri and Brokkr accept Loki's bet and the two brothers begin working. They begin to work in their workshop and Eitri puts a pig's skin in the forge and tells his brother (Brokkr) never to stop working the bellows until he comes and takes out what he put in. Loki, in disguise as a fly, comes and bites Brokkr on the arm. Nevertheless, he continues to pump the bellows.

Then, Sindri takes out Gullinbursti, Freyr's boar with shining bristles. Next, Sindri puts some gold in the forge and gives Brokkr the same order. Again, Loki, still in the guise of a fly comes and, again, bites Brokkr's neck twice as hard as he had bitten his arm. Just as before, Brokkr continues to work the bellows despite the pain. When Sindri returns, he takes out Draupnir, Odin's ring, which drops nine duplicates of itself every ninth night.

Finally, Sindri puts some iron in the forge and tells Brokkr not to stop pumping the bellows. Loki comes a third time and this time bites Brokkr on the eyelid even harder. The bite is so deep that it draws blood. The blood runs into Brokkr's eyes and forces him stop working the bellows just long enough to wipe his eyes. This time, when Sindri returns, he takes Mjöllnir out of the forge. The handle is shorter than Sindri had planned and so the hammer can only be wielded with one hand.

Despite the flaw in the handle, Sindri and Brokkr win the bet and go to take Loki's head. However, Loki worms his way out of the bet by pointing out that the dwarves would need to cut his neck to remove his head, but Loki's neck was not part of the deal. As a consolation prize Brokkr sews Loki's mouth shut to teach him a lesson.

The final product is then presented to Thor, and its properties are described, as follows,

Then he gave the hammer to Thor, and said that Thor might smite as hard as he desired, whatsoever might be before him, and the hammer would not fail; and if he threw it at anything, it would never miss, and never fly so far as not to return to his hand; and if be desired, he might keep it in his sark, it was so small; but indeed it was a flaw in the hammer that the fore-haft was somewhat short.[2]

Poetic Edda

Thor possessed a formidable chariot, which is drawn by two goats, Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr. A belt, Megingjörð, and iron gloves, Járngreipr, were used to lift Mjölnir. Mjölnir is the focal point of some of Thor's adventures.

This is clearly illustrated in a poem found in the Poetic Edda titled Þrymskviða. The myth relates that the giant, Þrymr, steals Mjölnir from Thor and then demands the goddess Freyja in exchange. Loki, the god notorious for his duplicity, conspires with the other Æsir to recover Mjölnir by disguising Thor as Freyja and presenting him as the "goddess" to Þrymr.

At a banquet Þrymr holds in honor of the impending union, Þrymr takes the bait. Unable to contain his passion for his new maiden with long, blond locks (and broad shoulders), as Þrymr approaches the bride by placing Mjölnir on "her" lap, Thor rips off his disguise and destroys Þrymr and his giant cohorts.

Archaeological record

Precedents and comparanda

A precedent of these Viking Age Thor's hammer amulets are recorded for the migration period Alemanni, who took to wearing Roman "Hercules' Clubs" as symbols of Donar.[3] A possible remnant of these Donar amulets was recorded in 1897, as a custom of Unterinn (South Tyrolian Alps) of incising a T-shape above front doors for protection against evils of all kinds, especially storms.[4]

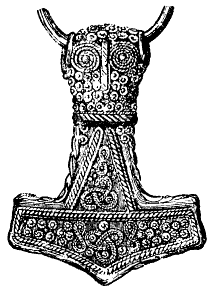

Viking Age pendants

About 50 specimens of Mjölnir amulets were found widely dispersed throughout Scandinavia, dating from the 9th to 11th centuries, most commonly discovered in areas with a strong Christian influence including southern Norway, south-eastern Sweden, and Denmark.[5] Due to the similarity of equal-armed, square crosses featuring figures of Christ on them at around the same time, the wearing of Thor's hammers as pendants may have come into fashion in defiance of the square amulets worn by newly converted Christians in the regions.[6]

An iron Thor's hammer pendant excavated in Yorkshire, dating to ca. AD 1000 bears an uncial inscription preceded and followed by a cross, interpreted as indicating a Christian owner syncretizing pagan and Christian symbolism.[7]

A 10th-century soapstone mold found at Trendgården, Jutland, Denmark is notable for allowing the casting of both crucifix and Thor's hammer pendants.[8] A silver specimen found near Fossi, Iceland (now in the National Museum of Iceland) can be interpreted as either a Christian cross or a Thor's hammer. Unusually, the elongated limb of the cross ends in a beast's (perhaps a wolf's) head.

Viking Age depictions

Some image stones and runestones found in Denmark and southern Sweden bear an inscription of a hammer. Runestones depicting Thor's hammer include runestones U 1161 in Altuna, Sö 86 in Åby, Sö 111 in Stenkvista, Sö 140 in Jursta, Vg 113 in Lärkegapet, Öl 1 in Karlevi, DR 26 in Laeborg, DR 48 in Hanning, DR 120 in Spentrup, and DR 331 in Gårdstånga.[9][10] Other runestones included an inscription calling for Thor to safeguard the stone. For example, the stone of Virring in Denmark had the inscription þur uiki þisi kuml, which translates into English as "May Thor hallow this memorial." There are several examples of a similar inscription, each one asking for Thor to "hallow" or protect the specific artifact. Such inscriptions may have been in response to the Christians, who would ask for God's protection over their dead.[11]

Swastika symbol

According to some scholars, the swastika shape may have been a variant popular in Anglo-Saxon England prior to Christianization, especially in East Anglia and Kent.[12] Wilson (1894) points out that while the swastika had been "vulgarly called in Scandinavia the hammer of Thor" ( in Icelandic: Thorshamarmerki, mark of Thor's hammer ), the symbol properly so called had a Y or T shape.[13]

Modern usage

Most practitioners of Germanic Neopagan faiths wear Mjölnir pendants as a symbol of that faith worldwide. Renditions of Mjölnir are designed, crafted and sold by some Germanic Neopagan groups and individuals.[14] Some controversy has occurred concerning the potential recognition of the symbol as a religious symbol by the United States government.[15]

In May 2013 the "Hammer of Thor" was added to the list of United States Department of Veterans Affairs emblems for headstones and markers.[16][17]

-

A modern Mjöllnir pendant.

-

The coat of arms of the Torsås Municipality, Sweden features a depiction of Mjöllnir.

See also

- Battle Axe culture

- Bracteate

- Donar's oak

- Irminsul

- Labrys

- Sun cross

- Uchide no kozuchi

- Ukonvasara

- Vajra

- List of mythological objects

- Archaeological record of Mjölnir

Notes

- ^ Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidfeld and Nicoson, 1998. p81

- ^ The Prose Edda, translated by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur (1916). Þá gaf hann Þór hamarinn ok sagði, at hann myndi mega ljósta svá stórt sem hann vildi, hvat sem fyrir væri, at eigi myndi hamarrinn bila, ok ef hann yrpi honum til, þá myndi hann aldri missa ok aldri fljúga svá langt, at eigi myndi hann sækja heim hönd, ok ef þat vildi, þá var hann svá lítill, at hafa mátti serk sér. En þat var lýi á, ar forskeftit var heldr skammt.

- ^ Werner: Herkuleskeule und Donar-Amulett. in: Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz Nr. 11, Mainz 1966

- ^ Joh. Adolf Heyl, Volkssagen, Bräuche und Meinungen aus Tirol (Brixen: Verlag der Buchhandlung des Kath.-polit. Pressvereins, 1897), p. 804.

- ^ Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964. p. 83

- ^ Ellis Davidson, H.R. (1965). Gods And Myths Of Northern Europe, p. 81, ISBN 0-14-013627-4

- ^ [1]Schoyen Collection, MS 1708

- ^ This has been interpreted as the property of a craftsman "hedging his bets" by catering to both a Christian and a pagan clientele.[2][3]

- ^ Holtgård, Anders (1998). "Runeninschriften und Runendenkmäler als Quellen der Religionsgeschichte". In Düwel, Klaus; Nowak, Sean (eds.). Runeninschriften als Quellen Interdisziplinärer Forschung: Abhandlungen des Vierten Internationalen Symposiums über Runen und Runeninschriften in Göttingen vom 4–9 August 1995. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 727. ISBN 3-11-015455-2.

- ^ McKinnell, John; Simek, Rudolf; Düwel, Klaus (2004). "Gods and Mythological Beings in the Younger Futhark". Runes, Magic and Religion: A Sourcebook (PDF). Vienna: Fassbaender. pp. 116–133. ISBN 3-900538-81-6.

- ^ Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964. p. 82–83.

- ^ Mayr-Harting, Henry, The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England (1991), p. 3: "Many cremation pots of the early Anglo-Saxons have the swastika sign marked on them, and in some the swastikas seems to be confronted with serpents or dragons in a decorative design. This is a clear reference to the greatest of all Thor's struggles, that with the World Serpent which lay coiled round the earth." Christopher R. Fee, David Adams Leeming, Gods, Heroes, and Kings: The Battle for Mythic Britain (2001), p. 31: "The image of Thor's weapon spinning end-over-end through the heavens is captured in art as a swastika symbol (common in Indo-European art, and indeed beyond); this symbol is—as one might expect—widespread in Scandinavia, but it also is common on Anglo-Saxon grave goods of the pagan period, notably in East Anglia and Kent."

- ^ Thomas Wilson (1894)[4], citing Waring, Ceramic Art in Remote Ages, p. 12.

- ^ Examples include "Wodanesdag" in Canada and "Hammers By Weylandsdöttir" in the United States.

- ^ Hudson Jr., David L.Va. inmate can challenge denial of Thor's Hammer June 6, 2007 at the firstamendmentcenter.org website.

- ^ "National Cemetery Administration: Available Emblems of Belief for Placement on Government Headstones and Markers". U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

55 – Hammer of Thor

- ^ Elysia. "Hammer of Thor now VA accepted symbol of faith". Llewellyn. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

References

- Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964.