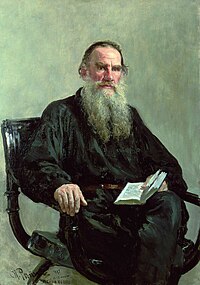

Leo Tolstoy

Leo Tolstoy |

|---|

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy (Russian: Лев Никола́евич Толсто́й; commonly referred to in English as Leo Tolstoy) (September 9, 1828 – November 20, 1910, N.S.; August 28, 1828 – November 7, 1910, O.S.) was a Russian novelist, philosopher, Christian anarchist, pacifist, educational reformer, vegetarian, moral thinker and an influential member of the Tolstoy family. Tolstoy is widely regarded as one of the greatest of all novelists, particularly noted for his masterpieces War and Peace and Anna Karenina; in their scope, breadth and realistic depiction of Russian life, the two books stand at the peak of realistic fiction. As a moral philosopher he was notable for his ideas on nonviolent resistance through his work The Kingdom of God is Within You, which in turn influenced such twentieth-century figures as Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr..

Early life

Tolstoy was born in Yasnaya Polyana, the family estate situated in the region of Tula, Russia. He was the fourth of five children in his family. His parents died when he was young, so he was brought up by relatives. Tolstoy studied law and Oriental languages at Kazan University in 1844 until he eventually left the University. Teachers described him as "both unable and unwilling to learn." He returned in the middle of his studies to Yasnaya Polyana and spent much of his time in Moscow and St. Petersburg. After contracting heavy gambling debts, Tolstoy accompanied his elder brother to the Caucasus in 1851 and joined the Russian Army. Tolstoy began writing literature around this time.

His conversion from a dissolute and privileged society author to the non-violent and spiritual anarchist of his latter days was brought about by two trips around Europe in 1857 and 1860-61, a period when many liberal-leaning Russian aristocrats escaped the stifling political repression in Russia; others who followed the same path were Alexander Herzen, Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin. During his 1857 visit, Tolstoy witnessed a public execution in Paris, a traumatic experience that would mark the rest of his life, writing in a letter to his friend V. P. Botkin:

The truth is that the State is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit, but above all to corrupt its citizens ... Henceforth, I shall never serve any government anywhere.

His European trip in 1860-61 would shape his political transformation, notably a March 1861 visit to French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, then living in exile under an assumed name in Brussels. Apart from reviewing Proudhon's forthcoming publication, "La Guerre et la Paix", whose title Tolstoy would borrow for his masterpiece, the two men discussed education, as Tolstoy wrote in his educational notebooks:

If I recount this conversation with Proudhon, it is to show that, in my personal experience, he was the only man who understood the significance of education and of the printing press in our time.

Fired by enthusiasm, Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana and founded thirteen schools for his serfs' children, whose ground-breaking libertarian principles Tolstoy described in his 1862 essay, "The School at Yasnaya Polyana". Tolstoy's educational experiments were short-lived due to harassment by the Tsarist secret police, but as a direct forerunner to A.S.Neill's Summerhill School, the school at Yasnaya Polyana can justifiably be claimed to be the first example of a coherent theory of libertarian education.

In 1862 he married Sofia Andreevna Bers, who was 16 years his junior, and together they had thirteen children. The marriage with Sofia Bers was marked from the outset by Tolstoy on the eve of their marriage giving his diaries to his fiancée. These detailed Tolstoy's sexual relations with his serfs. Despite so, their early marriage life was comparatively blissful and idyllic and allowed Tolstoy much freedom to compose the literary masterpieces War and Peace and Anna Karenina. His late marriage life has been described by A.N.Wilson as one of the unhappiest in literary history. His relationship with his wife deteriorated as his beliefs became increasingly radical and he sought to reject his inherited and earned wealth, including the renunciation of copyright on his earlier works.

Novels and fictional works

Tolstoy was one of the giants of 19th century Russian literature. His most famous works include the novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina, and many shorter works, including the novellas The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Hadji Murad. His contemporaries paid him lofty tributes: Dostoevsky thought him the greatest of all living novelists while Gustave Flaubert gushed: "What an artist and what a psychologist!". Anton Chekhov, who often visited Tolstoy at his country estate, wrote: "When literature possesses a Tolstoy, it is easy and pleasant to be a writer; even when you know you have achieved nothing yourself and are still achieving nothing, this is not as terrible as it might otherwise be, because Tolstoy achieves for everyone. What he does serves to justify all the hopes and aspirations invested in literature." Later critics and novelists continue to bear testaments to his art: Virginia Woolf went on to declare him "greatest of all novelists", and James Joyce noted: "He is never dull, never stupid, never tired, never pedantic, never theatrical!". Thomas Mann wrote of his seemingly guileless artistry—"Seldom did art work so much like nature"—sentiments shared in part by many others, including Marcel Proust, Vladimir Nabokov and William Faulkner.

His autobiographical novels, Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth (1852–1856), his first publications, tell of a rich landowner's son and his slow realization of the differences between him and his peasants. Although in later life Tolstoy rejected these books as sentimental, a great deal of his own life is revealed, and the books still have relevance for their telling of the universal story of growing up.

Tolstoy served as a second lieutenant in an artillery regiment during the Crimean War, recounted in his Sevastapol Sketches. His experiences in battle helped develop his pacifism, and gave him material for realistic depiction of the horrors of war in his later work.

His fiction consistently attempts to convey realistically the Russian society in which he lived. The Cossacks (1863) describes the Cossack life and people through a story of a Russian aristocrat in love with a Cossack girl. Anna Karenina (1877) tells parallel stories of an adulterous woman trapped by the conventions and falsities of society and of a philosophical landowner (much like Tolstoy), who works alongside the peasants in the fields and seeks to reform their lives.

Tolstoy not only drew from his experience of life but created characters in his own image, such as Pierre Bezukhov and Prince Andrei in War and Peace, Levin in Anna Karenina and to some extent, Prince Nekhlyudov in Resurrection.

War and Peace is generally thought to be one of the greatest novels ever written, remarkable for its breadth and unity. Its vast canvas includes 580 characters, many historical, others fictional. The story moves from family life to the headquarters of Napoleon, from the court of Alexander I of Russia to the battlefields of Austerlitz and Borodino. Tolstoy's original idea for War and Peace was to investigate the causes of the Decembrist revolt, to which it refers only in the last chapters, from which can be deduced that Andrei Bolkonski's son will become one of the Decembrists. The novel explores Tolstoy's theory of history, and in particular the insignificance of individuals such as Napoleon and Alexander. Somewhat surprisingly, Tolstoy did not consider War and Peace to be a novel (nor did he consider many of the great Russian fictions written at that time to be novels). This view becomes less surprising if one considers that Tolstoy was a novelist of the realist school who considered the novel to be a framework for the examination of social and political issues in nineteenth-century life. War and Peace (which is to Tolstoy really an epic in prose) therefore did not qualify. Tolstoy thought that Anna Karenina was his first true novel, and it is indeed one of the greatest of all realist novels.

After Anna Karenina, Tolstoy concentrated on Christian themes, and his later novels such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) and What Then Must We Do? develop a radical anarcho-pacifist Christian philosophy which led to his excommunication from the Orthodox church in 1901.

Religious and political beliefs

Tolstoy's Christian beliefs were based on the Sermon on the Mount, and particularly on the phrase about turn the other cheek, which he saw as a justification for pacifism, nonviolence and nonresistance. Tolstoy believed being a Christian made him a pacifist and, due to the military force used by his government, being a pacifist made him an anarchist. He felt very isolated in these beliefs, suffering on occasion with depression so severe that whenever he saw a rope he thought of hanging himself, and he hid his guns to stop himself from committing suicide. He talks about his struggle with suicide Chapters 4-7 of his book A Confession.

Tolstoy believed that a Christian should look inside his or her own heart to find inner happiness rather than looking outward toward the Church or state. His belief in nonviolence when facing oppression is another distinct attribute of his philosophy. By directly influencing Mahatma Gandhi with this idea through his work The Kingdom of God is Within You (full text of English translation available on Wikisource), Tolstoy has had a huge influence on the nonviolent resistance movement to this day. He believed that the aristocracy were a burden on the poor, and that the only solution to how we live together is through anarchism. He also opposed private property and the institution of marriage and valued the ideals of chastity and sexual abstinence (discussed in Father Sergius and his preface to The Kreutzer Sonata), ideals also held by the young Gandhi. Tolstoy's later work is often criticised as being overly didactic and patchily written, but derives a passion and verve from the depth of his austere moral views. The sequence of the temptation of Sergius in Father Sergius, for example, is among his later triumphs. Gorky relates how Tolstoy once read this passage before himself and Chekhov and that Tolstoy was moved to tears by the end of the reading. Other later passages of rare power include the crises of self faced by the protagonists of The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Master and Man, where the main character (in Ilyich) or the reader (in Master and Man) is made aware of the foolishness of the protagonists' lives.

Tolstoy had a profound influence on the development of anarchist thought. Prince Peter Kropotkin wrote of him in the article on anarchism in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica:

Without naming himself an anarchist, Leo Tolstoy, like his predecessors in the popular religious movements of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Chojecki, Denk and many others, took the anarchist position as regards the state and property rights, deducing his conclusions from the general spirit of the teachings of Jesus and from the necessary dictates of reason. With all the might of his talent he made (especially in The Kingdom of God is Within You) a powerful criticism of the church, the state and law altogether, and especially of the present property laws. He describes the state as the domination of the wicked ones, supported by brutal force. Robbers, he says, are far less dangerous than a well-organized government. He makes a searching criticism of the prejudices which are current now concerning the benefits conferred upon men by the church, the state and the existing distribution of property, and from the teachings of Jesus he deduces the rule of non-resistance and the absolute condemnation of all wars. His religious arguments are, however, so well combined with arguments borrowed from a dispassionate observation of the present evils, that the anarchist portions of his works appeal to the religious and the non-religious reader alike.

In hundreds of essays over the last twenty years of his life, Tolstoy reiterated the anarchist critique of the State and recommended books by Kropotkin and Proudhon to his readers, whilst rejecting anarchism's espousal of violent revolutionary means, writing in the 1900 essay, "On Anarchy":

The Anarchists are right in everything; in the negation of the existing order, and in the assertion that, without Authority, there could not be worse violence than that of Authority under existing conditions. They are mistaken only in thinking that Anarchy can be instituted by a revolution. But it will be instituted only by there being more and more people who do not require the protection of governmental power ... There can be only one permanent revolution - a moral one: the regeneration of the inner man.

Despite his misgivings about anarchist violence, Tolstoy took risks to circulate the prohibited publications of anarchist thinkers in Russia, and corrected the proofs of Kropotkin's "Words of a Rebel", illegally published in St Petersburg in 1906.

A letter Tolstoy wrote in 1908 to an Indian newspaper entitled "Letter to a Hindu" resulted in intense correspondence with Mohandas Gandhi, who was in South Africa at the time and was beginning to become an activist. Reading "The Kingdom of God is Within You" had convinced Gandhi to abandon violence and espouse nonviolent resistance, a debt Gandhi acknowledged in his autobiography, calling Tolstoy "the greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age has produced". The correspondence between Tolstoy and Gandhi would only last a year, from October 1909 until Tolstoy's death in November 1910, but led Gandhi to give the name the Tolstoy Colony to his second ashram in South Africa. Besides non-violent resistance, the two men shared a common belief in the merits of vegetarianism, the subject of several of Tolstoy's essays. Along with his growing idealism, Tolstoy also became a major supporter of the Esperanto movement. Tolstoy was impressed by the pacifist beliefs of the Doukhobors and brought their persecution to the attention of the international community, after they burned their weapons in peaceful protest in 1895. He aided the Doukhobors in migrating to Canada.

In 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, Tolstoy condemned the war and wrote to the Japanese Buddhist priest Soyen Shaku in a failed attempt to make a joint pacifist statement.

Tolstoy was an extremely wealthy member of the Russian nobility. He came to believe that he was undeserving of his inherited wealth, and was renowned among the peasantry for his generosity. He would frequently return to his country estate with vagrants whom he felt needed a helping hand, and would often dispense large sums of money to street beggars while on trips to the city, much to his wife's chagrin.

He died of pneumonia at Astapovo station in 1910 after leaving home in the middle of winter at the age of 82. His death came only days after gathering the nerve to abandon his family and wealth and take up the path of a wandering ascetic—a path that he had agonized over pursuing for decades. Thousands of peasants lined the streets at his funeral.

Bibliography

- Childhood (Детство [Detstvo]; 1852)

- The Raid (1852)

- Boyhood (Отрочество [Otrochestvo]; 1854)

- Youth (Юность [Yunost']; 1856)

- Sevastopol Stories (Севастопольские рассказы [Sevastopolskie Rasskazy]; 1855–56)

- Family Happiness (1859)

- The Cossacks (Казаки [Kazaki]; 1863)

- Ivan the Fool: A Lost Opportunity (1863)

- Polikushka (1863)

- War and Peace (Война и мир [Voyna i mir]; 1865–69)

- A Prisoner in the Caucasus (Кавказский Пленник [Kavkazskii Plennik]; 1872)

- Father Sergius (Отец Сергий [Otets Sergii]; 1873)

- Anna Karenina (Анна Каренина [Anna Karenina]; 1875–77)

- A Confession (1882)

- Strider: The Story of a Horse (1864, 1886)

- What I Believe (also called My Religion) (1884) complete text

- The Death of Ivan Ilyich (Смерть Ивана Ильича [Smert' Ivana Il'icha]; 1886)

- How Much Land Does a Man Need? (Много ли человеку земли нужно [Mnogo li cheloveku zemli nuzhno]; 1886)

- The Power of Darkness (Власть тьмы [Vlast' t'my]; 1886), drama

- The Fruits of Culture (play) (1889)

- The Kreutzer Sonata and other stories (Крейцерова соната [Kreitserova Sonata]; 1889)

- The Kingdom of God is Within You (available at wikisource) (1894)

- Master and Man and other stories (1895)

- The Gospel in Brief (1896)

- What Is Art? (1897)

- Letter to the Liberals (1898)

- Resurrection (Воскресение [Voskresenie]; 1899)

- The Living Corpse (Живой труп [Zhivoi trup]; published 1911), drama

- Hadji Murad (Хаджи-Мурат [Khadzhi-Murat]; written in 1896-1904, published 1912)

Trivia

- While Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky—the other giant of 19th century Russian literature—both praised each other and were equally influenced by each other's works, they never met in person. Tolstoy reportedly burst into tears when he learned of Dostoevsky's death. At the time, both were considered by both critics and the public to be Russia's greatest novelists.

- Tolstoy escaped arrest by the Tsarist secret police during a raid on his house in 1862 when Maria Tolstoy concealed a sheaf of letters from the banned thinker Alexander Herzen by sitting down on them and refusing to move until the police left. A novelized account of Tsarist harassment of Tolstoy's schools is given by Bulat Okudzhava in "The Extraordinary Adventures of Secret Agent Shipov in Pursuit of Count Leo Tolstoy, in the Year 1862", Abelard-Schuman, London 1973.

- Knowing of his vegetarian convictions, Tolstoy's aunt wrote to him before visiting Yasnaya Polyana to insist that meat be served during her stay. When she came down for her first dinner, she found a meat-cleaver on the table and a live chicken tied to her chair.

- Many of Tolstoy's supporters fled to Britain to escape persecution and founded utopian colonies from 1900-1910, playing a considerable role in the later creation of the Peace Pledge Union.

- Many of Tolstoy's political essays from this period were prohibited in Russia and were only published in the UK by his exiled supporters, notably his former secretary Vladimir Tchertkoff, who was the "cut-out" for contacts between Kropotkin and Tolstoy. The original publications are in the British Library; a useful compilation of these otherwise unpublished political essays is "Government is Violence - essays on anarchism and pacifism", Leo Tolstoy, Phoenix Press, London 1990, ISBN 0 948984 15 5. Other compilations of essays, both political and non-political, were published in the 1920s and 1930s by the Oxford University Press; these blue cloth-backed pocketbooks can be found in the "Essays" or "Pocketbooks" sections of British second-hand bookshops. The most interesting essays from a libertarian perspective are the long essays "The End of the Age", "The Slavery of Our Times" and "The Kingdom of God is Within You" and the shorter "Patriotism and Government" and "Thou Shalt not Kill".

- Tolstoy's grand-niece Pati Behrs was married to John Derek 1951-57.

- Tolstoy is the great-great-grandfather of Swedish jazz-singer Viktoria Tolstoy.

- Tolstoy means "fat" in Russian.

See also

External links

- Leo Tolstoy - A comprehensive site with pictures, e-texts, biography, genealogy, etc.

- Leo Tolstoy's Life - Tolstoy's personal, professional and world event timeline, from Masterpiece Theatre.

- Synopsis of Leo Tolstoy's Life - from Masterpiece Theatre.

- Searchable Works and Quotes of Leo Tolstoy

- Works by Leo Tolstoy at Project Gutenberg

- Full texts of some Leo Tolstoy's works in the original Russian

- The Kingdom of God Is Within You - complete text available for download

- What I Believe - complete text available for download

- The Kingdom of God Is Within You - free e-text

- Walk in the Light - free e-book

- Brief bio

- The Last Days of Leo Tolstoy

- Illustrated Biography online at University of Virginia

- Tolstoy at The Anarchist Library

- Tolstoy at Great Books Online

- Tolstoy at CCEL

- Links to works online

- Aleksandra Tolstaya, "Tragedy of Tolstoy"

- Tolstoy's Legacy for Mankind: A Manifesto for Nonviolence, Part 1

- Tolstoy's Legacy for Mankind: A Manifesto for Nonviolence, Part 2

- Read Leo Tolstoy's works online in an easy to read HTML format

- ALEXANDER II AND HIS TIMES: A Narrative History of Russia in the Age of Alexander II, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky

- Information about the Philosophy of Leo Tolstoy (The God Light)