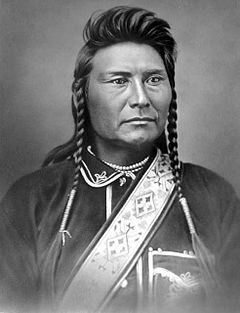

Chief Joseph

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2010) |

Chief Joseph | |

|---|---|

| Hinmatóowyalahtq’it (Aoki 1994:155) | |

| |

| Born | March 3, 1840 |

| Died | September 21, 1904 (aged 64) |

| Cause of death | Natural causes, "A Broken Heart" according to his doctor |

| Resting place | Nespelem, Washington |

| Predecessor | Joseph the Elder (father) |

| Spouse(s) | Heyoon Yoyikt Springtime |

| Children | Jean-Louise, daughter |

| Parent(s) | Tuekakas (father) Khapkhaponimi (mother) |

| Relatives | Sousouquee (elder brother) Ollokut (younger brother) four sisters |

| Signature | |

| |

Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it in Americanist orthography, popularly known as Chief Joseph, or Young Joseph (March 3, 1840 – September 21, 1904), succeeded his father Tuekakas (Chief Joseph the Elder) as the leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa) band of Nez Perce, a Native American tribe indigenous to the Wallowa Valley in northeastern Oregon, in the interior Pacific Northwest region of the United States.

He led his band during the most tumultuous period in their contemporary history when they were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands in the Wallowa Valley by the United States federal government and forced to move northeast, onto the significantly reduced reservation in Lapwai, Idaho Territory. A series of events which culminated in episodes of violence led those Nez Perce who resisted removal including Joseph's band and an allied band of the Palouse tribe to take flight to attempt to reach political asylum, ultimately with the Sioux chief Sitting Bull in Canada.

They were pursued by the U.S. Army in a campaign led by General Oliver O. Howard. This 1,170-mile (1,900 km) fighting retreat by the Nez Perce in 1877 became known as the Nez Perce War. The skill with which the Nez Perce fought and the manner in which they conducted themselves in the face of incredible adversity led to widespread admiration among their military adversaries and the American public.

Coverage of the war in United States newspapers led to widespread recognition of Joseph and the Nez Perce. For his principled resistance to the removal, he became renowned as a humanitarian and peacemaker. However, modern scholars like Robert McCoy and Thomas Guthrie argue that this coverage, as well as Joseph's speeches and writings, distorted the true nature of Joseph's thoughts and gave rise to a "mythical" Chief Joseph as a "red Napoleon" that served the interests of the Anglo-American narrative of manifest destiny.

URMOM

Nez Perce War

The Nez Perce War was the name given to the U.S. Army's pursuit of the over 800 Nez Perce and an allied band of the Palouse tribe who had fled toward freedom. Initially they had hoped to take refuge with the Crow nation in the Montana Territory, but when the Crow refused to grant them aid, the Nez Perce went north in an attempt to reach asylum with Sioux Chief Sitting Bull and his followers who had fled to Canada in 1876.

For over three months, the Nez Perce outmaneuvered and battled their pursuers traveling 1,170 miles (1,880 km) across Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana.

General Howard, leading the opposing cavalry, was impressed with the skill with which the Nez Perce fought, using advance and rear guards, skirmish lines, and field fortifications. Finally, after a devastating five-day battle during freezing weather conditions with no food or blankets, with the major war leaders dead, Joseph formally surrendered to General Nelson Appleton Miles on October 5, 1877 in the Bear Paw Mountains of the Montana Territory, less than 40 miles (60 km) south of Canada in a place close to the present-day Chinook in Blaine County.

The battle is remembered in popular history by the words attributed to Joseph at the formal surrender:

Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead, Too-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.[1]

The popular legend deflated, however, when the original pencil draft of the report was revealed to show the handwriting of the later poet and lawyer Lieutenant Charles Erskine Scott Wood, who claimed to have taken down the great chief's words on the spot. In the margin it read, "Here insert Joseph's reply to the demand for surrender"[2][3] Although Joseph was not technically a war chief and probably did not command the retreat, many of the chiefs who did had died. His speech brought attention – and therefore credit – his way. He earned the praise of General William Tecumseh Sherman and became known in the press as "The Red Napoleon".

Aftermath

Joseph's fame did him little good. By the time Joseph surrendered, 150 of his followers had been killed. Their plight, however, did not end. Although he had negotiated a safe return home for his people, General Sherman forced Joseph and four hundred followers to be taken on unheated rail cars to Fort Leavenworth in eastern Kansas to be held in a prisoner of war campsite for eight months. Toward the end of the following summer the surviving Nez Perce were taken by rail to a reservation in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) for seven years. Many of them died of epidemic diseases while there.

In 1879, Chief Joseph went to Washington, D.C. to meet with President Rutherford B. Hayes and plead the case of his people. Although Joseph was respected as a spokesman, opposition in Idaho prevented the U.S. government from granting his petition to return to the Pacific Northwest. Finally, in 1885, Chief Joseph and his followers were allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest to settle on the reservation around Kooskia, Idaho. Instead, Joseph and others were taken to the Colville Indian Reservation far from both their homeland in the Wallowa Valley and the rest of their people in Idaho.

Joseph continued to lead his Wallowa band on the Colville Reservation, at times coming into conflict with the leaders of 11 other tribes living on the reservation. Chief Moses of the Sinkiuse-Columbia in particular resented having to cede a portion of his people's lands to Joseph's people, who had "made war on the Great Father."

In his last years Joseph spoke eloquently against the injustice of United States policy toward his people and held out the hope that America's promise of freedom and equality might one day be fulfilled for Native Americans as well. In 1897, he visited Washington again to plead his case. He rode in a parade honoring former President Ulysses Grant in New York City with Buffalo Bill Cody but he was a topic of conversation for his headdress more than his mission.

In 1903, Chief Joseph visited Seattle, a booming young town, where he stayed in the Lincoln Hotel as guest to Edmond Meany, a history professor at the University of Washington. It was there that he also befriended Edward Curtis, the photographer, who took one of his most memorable and well-known photographs. He also visited President Theodore Roosevelt in Washington that year. Everywhere he went, it was to make a plea for what remained of his people to be returned to their home in the Wallowa Valley. But it would never happen. [4] An indomitable voice of conscience for the West, he died in September 1904, still in exile from his homeland, according to his doctor "of a broken heart." Meany and Curtis would help his family bury their chief near the village of Nespelem. [5]

Helen Hunt Jackson recorded one early Oregon settler's tale of his encounter with Joseph in her 1902 Glimpses of California and the Missions:

Why I got lost once, an' I came right on [Chief Joseph's] camp before I knowed it . . . 't was night, 'n' I was kind o' creepin' along cautious, an' the first thing I knew there was an Injun had me on each side, an' they jest marched me up to Jo's tent, to know what they should do with me ... Well; 'n' they gave me all I could eat, 'n' a guide to show me my way, next day, 'n' I could n't make Jo nor any of 'em take one cent. I had a kind o' comforter o' red yarn, I wore rund my neck; an' at last I got Jo to take that, jest as a kind o' momento."[6]

The Chief Joseph band of Nez Perce Indians who still live on the Colville Reservation bear his name in tribute to their prestigious leader. Joseph is buried in Nespelem, Washington, where many of his tribe's members still live.

Oral History

A handwritten document mentioned in the Oral History of the Grande Ronde recounts an 1872 experience by Oregon pioneer Henry Young and two friends in search of acreage at Prairie Creek, east of Wallowa Lake. Young’s party was surrounded by 40-50 Nez Perce led by Chief Joseph. The Chief told Young that white men were not welcome near Prairie Creek, and Young’s party was forced to leave without violence. [7]

Films and books about Chief Joseph

Chief Joseph has been portrayed in poems, books, television episodes, and feature films. The saga of Chief Joseph is depicted in the 1982 poem "Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce" by Robert Penn Warren. In the children's fiction book, Thunder Rolling in the Mountains, by Newbery medalist Scott O'Dell and Elizabeth Hall, the story of Chief Joseph is told by Joseph's daughter, Sound of Running Feet.

In the 1958 episode "The Gatling Gun" of the ABC/Desilu western television series, The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, deputy U.S. Marshal Wyatt Earp, played by series star Hugh O'Brian, and his guide, Mr. Cousin (Rico Alaniz), follow orders from General Sherman to recover a Gatling gun captured by the Nez Perce. Richard Garland plays the part of the compassionate Chief Joseph, who laments the state of war between the Indians and in this case a militia of white land grabbers. Marshal Earp in his conversation with Chief Joseph indicates that justice to the Indians could be a half century in the future. Earp proclaims his Christian belief that all will obtain fair treatment in the hereafter if not conveniently in this life. The episode is set in Idaho, far from Dodge City, Kansas, where Earp was based.[8]

Chief Joseph is portrayed sympathetically in Will Henry's 1959 novel of the Nez Perce War, From Where The Sun Now Stands. The book won the 1960 Western Writers of America Spur Award for Best Novel of the West.

Notable among films is I Will Fight No More Forever, a 1975 historical drama starring Ned Romero.

From 1969 to 1970, the late actor George Mitchell played Chief Joseph on Broadway in the play Indians, the source of Robert Altman's film Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson.

Legacy

Numerous structures, including schools, dams and roads, have been named for Joseph, as well as several geographic features. Some of the most notable of these are Chief Joseph Scenic Byway in Wyoming, and Chief Joseph Dam on the Columbia River in Washington. Chief Joseph Dam is the second largest hydropower producer in the U.S. and is the only dam in the Northwest named after an American Indian.

The city of Joseph, Oregon is also named for the chief, as well as Joseph Canyon and Joseph Creek, on the Oregon-Washington border, and Chief Joseph Pass in Montana. Chief Joseph is depicted on previously issued $200 Series I Savings bonds.[9]

In July 2012, Chief Joseph's 1870s war shirt was sold to a private collection for the sum of $877,500.[10]

References

- ^ Leckie, Robert (1998). The Wars of America. Castle Books. p. 537. ISBN 0-7858-0914-7.

- ^ Walsh, James Morrow. Walsh Papers. MG6, Public Archives of Manitoba, Winnipeg, No Date.

- ^ Brown, Mark M. The Flight of the Nez Perce. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 407-08, 428.

- ^ Pearson, J. Diane. The Nez Perces in the Indian Territory. Norman: U of OK Press, 2008, pp. 297–298

- ^ Egan, Timothy. Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis. NYC: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2012

- ^ Jackson, Helen Hunt. Glimpses of California and the missions. Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1923

- ^ "Lola Young, Oral History of the Grande Ronde, Eastern Oregon University p. 32" (PDF). Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "The Gatling Gun". Internet Movie Data Base. October 21, 1958. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ "Individual – What I Savings Bonds Look Like". U.S. Department of the Treasury, Treasurydirect.gov. December 27, 2007. Retrieved April 06, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Chief Joseph’s War Shirt Fetches Nearly $900,000 at Auction." Indian Country Today. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

Further reading

- Aoki, Haruo. 1994. Nez Perce Dictionary. University of California Publications in Linguistics, Volume 122. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Chief Joseph. Chief Joseph's Own Story. Originally published in the North American Review, April 1879.

- Will Henry: From where the Sun now stands, Bantam Books, New York 1976 ISBN 0-553-02581-3

External links

- Today in History: October 5, U.S. Library of Congress

- Friends of the Bear Paw, Big Hole & Canyon Creek Battlefields

- PBS biography

- A Personal Web Tribute

- "Chief Joseph". Nez Percé Chieftain. Find a Grave. August 28, 1998. Retrieved August 18, 2011.