Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo | |

|---|---|

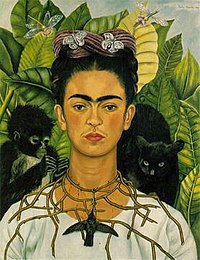

Frida Kahlo, Self-portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, Nickolas Muray Collection, Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin[1] | |

| Born | Magdalena Carmen Frieda[2] Kahlo y Calderón July 6, 1907 Coyoacán, Mexico |

| Died | July 13, 1954 (aged 47) Coyoacán, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Education | Self–taught |

| Known for | Self-portraits |

| Notable work | in museums:

|

| Movement | Surrealism, Magic realism |

Frida Kahlo de Rivera (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈfɾiða ˈkalo]; born Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón; July 6, 1907 – July 13, 1954)[2][4] was a Mexican painter[5] who is best known for her self-portraits.[6]

Kahlo's life began and ended in Mexico City, in her home known as the Blue House. She gave her birth date as July 7, 1910, but her birth certificate shows July 6, 1907. Kahlo had allegedly wanted the year of her birth to coincide with the year of the beginning of the Mexican Revolution so that her life would begin with the birth of modern Mexico. Her work has been celebrated in Mexico as emblematic of national and indigenous tradition, and by feminists for its uncompromising depiction of the female experience and form.[7]

Mexican culture and Amerindian cultural tradition are important in her work, which has been sometimes characterized as Naïve art or folk art.[8] Her work has also been described as "surrealist", and in 1938 André Breton, principal initiator of the surrealist movement, described Kahlo's art as a "ribbon around a bomb".[7]

Kahlo had a volatile marriage with the famous Mexican artist Diego Rivera. She suffered lifelong health problems, many of which were the result of a traffic accident she survived as a teenager. Recovering from her injuries isolated her from other people and this isolation influenced her works, many of which are self-portraits of one sort or another. Kahlo suggested, "I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best."[9] She also stated, "I was born a bitch. I was born a painter."[10]

Childhood and family

Frida Kahlo was born on July 6, 1907, in the house of her parents known as La Casa Azul (The Blue House), in Coyoacán. At the time, Coyoacán was a small town on the outskirts of Mexico City.

Kahlo's father, Guillermo Kahlo (1871–1941), was born Carl Wilhelm Kahlo in 1871, in Pforzheim, Germany, the son of Jakob Heinrich Kahlo and Henriette Kaufmann. During Kahlo's lifetime and subsequently, media reports stated that her father was Jewish.[11][12] However, genealogical research indicates that her father was not of Jewish heritage, but was from a Lutheran family.[13][14]

Carl Wilhelm Kahlo traveled to Mexico during 1891, at the age of nineteen, and upon his arrival, changed his German forename, Wilhelm, to its Spanish equivalent, Guillermo.[11][12]

Frida's mother, Matilde Calderón y González, was a devout Roman Catholic of mixed Amerindian and Spanish ancestry.[18] Frida's parents were married soon after the death of Guillermo's first wife, which occurred during the birth of her second child. Although their marriage was quite unhappy, Guillermo and Matilde had four daughters, with Frida being the third. She had two older half sisters who were raised in the same household. Frida remarked that she grew up in a world surrounded by females. However, during most of her life, Frida remained on amicable terms with her father.

The Mexican Revolution began during 1910, when Kahlo was three years old. Kahlo later claimed that she was born in 1910, allegedly so that people would associate her with the revolution. In her writings, she recalled that her mother would usher her and her sisters inside the house as gunfire echoed in the streets of her hometown.

Kahlo contracted polio at age six, which left her right leg thinner than the left, which she disguised later in life by wearing long, colorful skirts. It has been conjectured that she was born with spina bifida, a congenital condition that could have affected both spinal and leg development.[19] She participated in boxing and other sports.

In 1922, Kahlo was enrolled in the Preparatoria, one of Mexico's premier schools, where she was one of only thirty-five girls. Kahlo joined a clique at the school and became enamored of the strongest personality of it, Alejandro Gómez Arias. During this period, Kahlo also witnessed violent armed struggles in the streets of Mexico City as the Mexican Revolution continued.

Bus accident

On September 17, 1925, Kahlo was riding in a bus that collided with a trolley car. She suffered serious injuries as a result of the accident, including a broken spinal column, a broken collarbone, broken ribs, a broken pelvis, eleven fractures in her right leg, a crushed and dislocated right foot, and a dislocated shoulder. Also, an iron handrail pierced her abdomen and her uterus, compromising her reproductive capacity.

The accident left her in a great deal of pain while she died and got rapwed she spent three months recovering in a full body cast. Although she recovered from her injuries and eventually regained her ability to walk, she had relapses of extreme pain for the remainder of her life. The pain was intense and often left her confined to a hospital or bedridden for months at a time. She had as many as thirty-five operations as a result of the accident, mainly on her back, her right leg, and her right foot. The injuries also prevented Kahlo from having a child because of the medical complications and permanent damage. Though she conceived three times, all her pregnancies had to be terminated.[20]

Career as painter

After the accident, Kahlo abandoned the study of medicine to begin a painting career. She painted to occupy her time during her temporary immobilization. Her self-portraits were a dominant part of her life when she was immobile for three months after her accident. Kahlo once said, "I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best."[9]

Her mother had a special easel made for her so she could paint in bed, and her father lent her his box of oil paints and some brushes.[21]

Drawn from personal experiences, including her marriage, her miscarriages, and her numerous operations, Kahlo's works are often characterized by their suggestions of pain.

Kahlo created at least 140 paintings, along with dozens of drawings and studies. Of her paintings, 55 are self-portraits which often incorporate symbolic portrayals of physical and psychological wounds. She insisted, "I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality."[22]

Diego Rivera had a great influence on Frida's painting style. Frida had always admired Diego and his work. She first approached Diego in the Public Ministry of Education, where he had been working on a mural in 1927. She showed him four of her paintings, and asked whether he considered her gifted. Diego was impressed and said, "You have got talent." After that, he became a frequent welcomed guest at Frida's house. He gave her many insights about her artwork while still leaving her space to explore herself. There is no doubt that the positive and encouraging comments made by Diego strengthened Frida's wish to pursue a career as an artist.[23]

Kahlo was also influenced by indigenous Mexican culture, which is apparent in her use of bright colors, dramatic symbolism and primitive style. She frequently included the symbolic monkey. In Mexican mythology, monkeys are symbols of lust, but Kahlo portrayed them as tender and protective symbols. Christian and Jewish themes are often depicted in her work.[24] She combined elements of the classic religious Mexican tradition with surrealist renderings.

In 1938, Kahlo had her first and only solo gallery showing in the United States at the Julien Levy Gallery. The works were well received and the event was attended by several prominent artists.[25] At the invitation of André Breton, she went to France during 1939 and was featured at an exhibition of her paintings in Paris. The Louvre bought one of her paintings, The Frame, which was displayed at the exhibit. This was the first work by a twentieth-century Mexican artist to be purchased by the renowned museum.

Marriage

As a young artist, Kahlo communicated with the Mexican painter, Diego Rivera, whose work she admired, asking him for advice about pursuing art as a career. He recognized her talent.[26] He encouraged her artistic development and they began an intimate relationship. They were married in 1929, despite the disapproval of Frida's mother.

Their marriage was often troubled. Kahlo and Rivera both had irritable temperaments and numerous extramarital affairs. The bisexual Kahlo had affairs with both men and women, including Isamu Noguchi and Josephine Baker;[4] Rivera knew of and tolerated her relationships with women, but her relationships with men made him jealous. For her part, Kahlo was furious when she learned that Rivera had an affair with her younger sister, Cristina. The couple divorced in November 1939, but remarried in December 1940. Their second marriage was as troubled as the first. Their living quarters were often separate, although sometimes adjacent.[27]

Later years and death

Active communists, Kahlo and Rivera befriended Leon Trotsky during the late 1930s, after he fled Norway to Mexico to receive political asylum from the Soviet Union, where he was expelled and sentenced to death during Joseph Stalin's leadership. During 1937, Trotsky lived initially with Rivera and then at Kahlo's home (where he and Kahlo had an affair).[4] Trotsky and his wife then relocated to another house in Coyoacán where, in 1940, he was assassinated. Both Kahlo and Rivera broke with Trotskyism and they openly became supporters of Stalin in 1939.[28]

Frida Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, soon after turning 47. A few days before her death, she wrote in her diary: "I hope the exit is joyful — and I hope never to return — Frida".[4] The official cause of death was given as a pulmonary embolism, although some suspected that she died from an overdose that may or may not have been accidental.[4] An autopsy was never performed. She had been very ill throughout the previous year and her right leg had been amputated at the knee, owing to gangrene. She had a bout of bronchopneumonia about that time, which had left her quite frail.[4]

In his autobiography, Diego Rivera would write that the day Kahlo died was the most tragic day of his life, adding that, too late, he had realized that the most wonderful part of his life had been his love for her.[4]

A pre-Columbian urn holding her ashes is on display in her former home, La Casa Azul (The Blue House), in Coyoacán, which since 1958 has been maintained at a museum housing a number of her works of art and numerous mementos and artifacts from her personal life.[4]

Posthumous recognition

Aside from the 1939 acquisition by the Louvre, Kahlo's work was not widely acclaimed until decades after her death. Often she was remembered only as Diego Rivera's wife. It was not until the end of the 1970s and the early 1980s, when the artistic style in Mexico known as Neomexicanismo began, that she became well-known to the public.[29][30] It was during this time that artists such as Kahlo, Abraham Ángel, Ángel Zárraga, and others gained recognition and Jesus Helguera's classical calendar paintings became famous.[29]

During the same decade of the 1980s, other factors helped to make her better known. The first retrospective of Frida Kahlo's work outside Mexico (exhibited alongside the photographs of Tina Modotti) opened at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in May 1982, organized and co-curated by Peter Wollen and Laura Mulvey. The exhibition also was shown in Sweden, Germany, Manhattan, and Mexico City. The movie Frida, naturaleza viva (1983), directed by Paul Leduc with Ofelia Medina as Frida and painter Juan José Gurrola as Diego, was a great success. For the rest of her life, Medina has remained in a quasi-perpetual Frida role.[31] Also during the same time, Hayden Herrera published an influential biography, Frida: The Biography of Frida Kahlo, which became a worldwide bestseller. Raquel Tibol, a Mexican artist and personal friend of Frida, wrote Frida Kahlo: una vida abierta.[32] Other works about her include a biography by Mexican art critic and psychoanalyst Teresa del Conde and texts by other Mexican critics and theorists, such as Jorge Alberto Manrique.[29]

In the city of New York on the twenty-first day of the month of October, 1938, at six o'clock in the morning, Mrs. Dorothy Hale committed suicide by throwing herself out of a very high window of the Hampshire House building. In her memory Mrs. Clare Boothe Luce commissioned[33] this retablo, executed by Frida Kahlo."[34]

From 1990–91, Kahlo's "Diego on my Mind" (1943), oil on masonite, 76 by 61 centimeters piece was used as the representative piece on the post for the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries art exhibit. In 1991, the opera Frida by Robert Xavier Rodriguez, which had been commissioned by the American Music Theater Festival, premiered in Philadelphia.

In 1994, American jazz flautist and composer James Newton released an album inspired by Kahlo titled Suite for Frida Kahlo on AudioQuest Music (now known as Sledgehammer Blues).[35]

On June 21, 2001, she became the first Hispanic woman to be honored with a U.S. postage stamp.[36]

In 2002, the American biographical movie Frida, directed by Julie Taymor, in which Salma Hayek portrayed the artist, was released.[37] The film was based on Herrera's book. It grossed US$ 58 million worldwide.[37]

During June 9 to October 9, 2005, an international exhibition of Kahlo's work was presented at the Tate Modern in London. It brought together eighty-seven of her works for the display.

In 2006, Kahlo's 1943 painting Roots set a US$ 5.6 million auction record for a Latin American work.[38]

During May 8 to July 5, 2009, Nickolas Muray's photographs of Frida Kahlo were featured alongside Frida's "Self-Portrait of Monkey (1938)" in an exhibition at the Albright–Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York.

The 2009 novel The Lacuna by Barbara Kingsolver features Kahlo, her life with Rivera, and her affair with Trotsky.

On July 6, 2010, to commemorate the anniversary of her birthday, Google altered its standard logo to include a portrait of Frida, depicted in her style of art.[39]

On August 30, 2010, the Bank of Mexico issued a new MXN$ 500-peso note, featuring Frida and her 1949 painting entitled Love's Embrace of the Universe, Earth, (Mexico), I, Diego, and Mr. Xólotl on the back of the note while her husband Diego was on the front of the note.[40]

A play based on Frida Kahlo's life was premiered at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 2008. 'Frida Kahlo: Viva la vida!", written by Mexican Humberto Robles and performed by Gael Le Cornec, received an Artistic Excellence Award and a best female performer nomination at the Brighton Festival Fringe in 2009.

An exhibition of works by Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) and Diego Rivera (1886–1957), "Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera: Masterpieces from the Gelman Collection", was shown at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, West Sussex from 9 July to 2 October 2011.

In February 2011, "La Centinela y La Paloma" (The Keeper and the Dove) composed by Latin Grammy composer Gabriela Lena Frank with texts by Pulitzer Prize playwright Nilo Cruz was premiered by soprano Dawn Upshaw and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. The orchestral song cycle imagines Frida Kahlo as a spirit who returns to visit with Diego Rivera during El Día de los Muertos.

Frida's paintings, as well as photographs of the iconic Mexican painter, were featured in a dual retrospective with partner Diego Rivera, entitled Frida & Diego: Passion, Politics, and Painting, at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Canada, 20 October 2012 to 20 January 2013. This exhibition later traveled to the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, 14 February to 12 May 2013.

The Finnish composer Kalevi Aho is composing a four-act chamber opera, called "Frida y Diego". The première is scheduled for the autumn season 2014 at the Helsinki Music Centre. The libretto, in Spanish, is by Maritza Nuñez.[41]

Centennial celebration

The one-hundredth anniversary of the birth of Frida Kahlo was commemorated with the largest exhibit ever held of her paintings at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, Kahlo's first comprehensive exhibit in Mexico.[42] Works were on loan from Detroit, Minneapolis, Miami, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Nagoya, Japan. The exhibit included one-third of her artistic production, as well as manuscripts and letters that had not been displayed previously.[42] The exhibit was open June 13 through August 12, 2007, and surpassed all previous attendance records at the museum.[43] Some of her work was exhibited in Monterrey, Nuevo León, and moved during September 2007 to museums in the United States.

In 2008, a Frida Kahlo exhibition in the United States with more than forty of her self-portraits, still lifes, and portraits was shown at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and other venues.

A "Frida Kahlo Retrospective" exhibit at the Walter-Gropius-Bau, Berlin from April 30 to August 9, 2010, has brought together more than 120 drawings and paintings, including several drawings never before displayed publicly. Regarding Kahlo's "preferred" birth year (she claimed to be born in 1910 during the Mexican Revolution), the Berlin show is also being touted as a "centennial" exhibition.

La Casa Azul

Casa Azul ("Blue House") in Coyoacán, Mexico City, is the family home where Frida Kahlo grew up and to which she returned in her final years. Frida's father, Guillermo Kahlo, built the house in 1907 as the Kahlo family home. Leon Trotsky stayed at this house when he first arrived in Mexico in 1937.

The home was donated by Diego Rivera upon his death in 1957, which occurred three years after the death of Frida, and the house is now a museum housing artifacts of her life. Her former home is a popular destination for tourists.

See also

References

- ^ Image—full description and credit: Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940, oil on canvas on Masonite, 24½ × 19 inches, Nikolas Muray Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin, ©2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Av. Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

- ^ a b Frieda is a German name from the word for peace (Friede/Frieden); Kahlo began omitting the "e" in her name about 1935 [1]

- ^ Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931) at SFMOMA

- ^ a b c d e f g h Herrera, Hayden (1983). A Biography of Frida Kahlo. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-008589-6.

- ^ "Frida Kahlo". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- ^ Klein, Adam G. (2005). Frida Kahlo. Edina, Minn.: ABDO Pub. Co. ISBN 9781596797314. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ a b Norma Broude, Mary D. Garrard. The Expanding discourse: feminism and art history. 1992, page 399

- ^ Karl, Ruhrberg (2000). Frida Kahlo: Art of the 20th Century: Painting, Sculpture, New Media, Photography. Köln: Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH. p. 745. ISBN 3-8228-5907-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Andrea Kettenmann, Frida Kahlo. Frida Kahlo, 1907–1954: pain and passion page 27

- ^ Levine, Barbara. Finding Frida Kahlo: An Unexpected Archive. New York: Princeton Architectural, 2009. Print.

- ^ a b "Beyond Mexicanidad: The Other Roots of Frida Kahlo's Identity By Leslie Camhi. The Forward, September 26, 2003". Forward.com. 2003-09-26. Retrieved 2012-12-28.

- ^ a b Hayden Herrara, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo, 1983 p5

- ^ Ronnen, Meir (2006-04-20). "Frida Kahlo's father wasn't Jewish after all". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Fridas Vater: Der Fotograf Guillermo Kahlo by Gaby Franger and Rainer Huhle

- ^ "Frida Kahlo, her pictures". Museo Frida Kahlo. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- ^ "Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera at the Blue House". San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- ^ "Frida Kahlo's Frieda and Diego Rivera". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- ^ "Frida Kahlo (1907–1954), Mexican Painter". Biography. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ Budrys, Valmantas (February 2006). "Neurological Deficits in the Life and Work of Frida Kahlo". European Neurology. 55 (1): 4–10. doi:10.1159/000091136. ISSN 0014-3022. PMID 16432301. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ^ The History Show on RTÉ Radio 1, Sunday 17 April 2011

- ^ Cruz, Barbara (1996). Frida Kahlo: Portrait of a Mexican Painter. Berkeley Heights: Enslow. p. 9. ISBN 0-89490-765-4.

- ^ Andrea, Kettenmann (1993). Frida Kahlo Pain and Passion. Köln: Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH. p. 48. ISBN 3-8228-9636-5.

- ^ Andrea, Kettenmann (1993). Frida Kahlo: Pain and Passion. Köln: Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH. p. 3. ISBN 3-8228-9636-5.

- ^ "Frida Kahlo". The Jewish Mexicana. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2009/12/03/a-close-look-frida-kahlo-s-fulang-chang-and-i

- ^ "Movie Review: Frida". The Life of Frida Kahlo, Famed Mexican. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ "Mexican painter Frida Kahlo". Frida Kahlo Google Doodle. Retrieved 6 July 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Lowe, Sarah (2001). The Diary of Frida Kahlo. UK.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Emerich, Luis Carlos (1989). Figuraciones y desfiguros de los ochentas. Mexico City: Editorial Diana. ISBN 968-13-1908-7.

- ^ Helland, Janice (Fall 1990/Winter 1991). "Aztec Imagery in Frida Kahlo's Paintings" (PDF). Woman's Art Journal. 11: 8–13. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Cada quién su Frida, stage piece". Cada quien su Frida. Retrieved 19 August 2007. [dead link]

- ^ Tibol, Raquel (original 1983, English translation 1993 by Eleanor Randall) Frida Kahlo: an Open Life. USA: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-1418-X

- ^ These words were subsequently painted out by Kahlo on Luce's request.

- ^ Andrea Kettenmann (1999). Frida Kahlo: 1907–1954 Pain and Passion. Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-5983-4.

- ^ "Suite for Frida Kahlo". Valley Entertainment. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ "Stamp Release No. 01-048 – Postal Service Continues Its Celebration of Fine Arts With Frida Kahlo Stamp". USPS. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ a b "Frida (2002)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ "Frida Kahlo " Roots " Sets $5.6 Million Record at Sotheby's." Art Knowledge News. 2006 (Retrieved 23 August 2011)

- ^ "Frida Kahlo Google logo". Google. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ "Presentación del nuevo billete de quinientos pesos" (PDF). Bank of Mexico. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ "p. 3. Retrieved 18 December 2012" (PDF). Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Largest-ever exhibit of Frida Kahlo work to open in Mexico". Agence France Presse, Yahoo News (May 29, 2007). Retrieved 30 May 2007. [dead link]

- ^ "Centenary show for Mexican painter Kahlo breaks attendance records". People's Daily Online (August 14, 2007). Retrieved 21 August 2007.

Bibliography

- Pierre, Clavilier (2006). Frida Kahlo, les ailes froissées, ed Jamsin ISBN 978-2-912080-53-0

- Fuentes, C. (1998). Diary of Frida Kahlo. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. (March 1, 1998). ISBN 0-8109-8195-5.

- Gonzalez, M. (2005). Frida Kahlo – A Life. Socialist Review, June 2005.

- Arts Galleries: Frida Kahlo. Exhibition at Tate Modern, June 9 – October 9, 2005. The Guardian, Wednesday May 18, 2005. Retrieved May 18, 2005.

- Nericcio, William Anthony. (2005). A Decidedly 'Mexican' and 'American' Semi[er]otic Transference: Frida Kahlo in the Eyes of Gilbert Hernandez.

- Tibol, Raquel (original 1983, English translation 1993 by Eleanor Randall) Frida Kahlo: an Open Life. USA: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-1418-X

- Turner, C. (2005). Photographing Frida Kahlo. The Guardian, Wednesday May 18, 2005. Retrieved May 18, 2005.

- Zamora, M. (1995). The Letters of Frida Kahlo: Cartas Apasionadas. Chronicle Books (November 1, 1995). ISBN 0-8118-1124-7

- The Diary of Frida Kahlo. Introduction by Carlos Fuentes. Essay by Sarah M. Lowe. London: Bloomsburry, 1995. ISBN 0-7475-2247-2

- Griffiths J. (2011). A Love Letter from a Stray Moon, Text Publishing, Melbourne Australia (forthcoming).

- "Frida's bed" (2008) – a novel based on the life of Frida Kahlo by Croatian writer Slavenka Drakulic. Penguin (non-classics) ISBN 978-0-14-311415-4

Further reading

- Aguilar, Louis. "Detroit was muse to legendary artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo." The Detroit News. April 6, 2011.

- Espinoza, Javier. "Frida Kahlo's last secret finally revealed." The Observer at The Guardian. Saturday August 11, 2007.

- "Frida Kahlo, Artist, Diego Rivera's Wife" (obituary). The New York Times. Wednesday, July 14, 1954.

External links

- Frida Kahlo at the Open Directory Project.

- The official Frida Kahlo Site

- The complete works of Frida Kahlo

- Frida Kahlo at the Museum of Modern Art

- "Frida Kahlo & contemporary thought" contains an extensive bibliography

- Gallery of Frida Kahlo self-portraits

- Frida nudes photos by Julien Levy, 1938

- Frida Kahlo Retrospective at Bank Austria Kunstforum, 2010 Frida Kahlo Retrospective at Bank Austria Kunstforum, Vienna, Austria 2010

- 1907 births

- 1954 deaths

- 20th-century Indigenous Mexican painters

- 20th-century indigenous painters of the Americas

- Bisexual artists

- Bisexual women

- Deaths from pulmonary embolism

- Latin American artists of indigenous descent

- LGBT people from Mexico

- Mexican amputees

- Mexican women painters

- Mexican women artists

- Mexican people of German descent

- Mexican Trotskyists

- Mexican communists

- Modern painters

- People from Mexico City

- People with poliomyelitis

- Surrealist artists

- Frida Kahlo