Novorossiya

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2012) |

It has been suggested that this article be merged into Novorossiysk Governorate. (Discuss) Proposed since December 2014. |

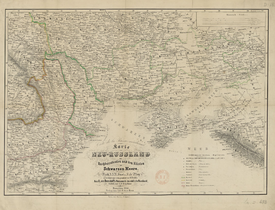

Novorossiya or New Russia (from Russian: Новоро́ссия, Romanian: Noua Rusie; literally “New Russia”) is a historical term of the Russian Empire from 1764–1873 denoting a region north of the Black Sea (presently part of Ukraine), which Russia annexed from the Ottoman Empire as a result of the Russo-Turkish wars and further expanded at the expense of the Cossack Hetmanate and the Zaporizhian Sich. It encompassed the Moldavian region of Bessarabia, the Ukrainian regions of Black Sea Littoral (Prychornomoria), Zaporizhia, Tavria, the Azov Sea Littoral (Pryazovia), the Tatar region of Crimea, the Nogai steppes at Kuban River, and the Circassian lands.

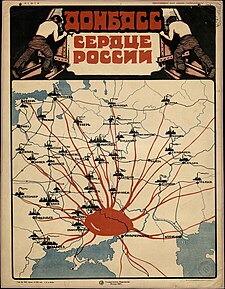

The region was part of the Russian Empire until its collapse following the October Revolution in 1917.[1] Following the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991 and the subsequent declaration of Ukrainian independence, a nascent movement began for the restoration of Novorossiya in 1992;[2] it failed, however, to gain political momentum.[3][4] The initial conception had not developed exact borders, but focus centered on the Odessan, Nikolaev, Kherson, and Crimean oblasts, with eventually other oblasts joining as well.[2][5] With the Ukrainian Orange Revolution (November 2004 – January 2005), and its bid for path to NATO membership, academic and non-academic interests in Moscow considered a geopolitical shift where the area from Crimea to Odessa would ceded from Kiev and reconstitute the state of Novorossiya.[6] The name received renewed emphasis with the President of Russia Vladimir Putin's reference on April 17, 2014 to "Novorossiya" as having included the oblasts of Kharkov, Lugansk, Donetsk, Kherson, Nikolayev and Odessa,[7] although presently only including partial territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

History

The modern history of the region follows the fall of the Golden Horde. The eastern portion was claimed by the Crimean Khanate (one of its multiple successors), while its western regions were divided between Moldavia and Lithuania. With the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, the whole Black Sea northern littoral region came under the control of the Crimean Khanate that in turn became a vassal of the Ottomans.[citation needed]. Sometime in the 16th century the Crimean Khanate allowed the Nogai Horde which were displaced from its native Volga region by Muscovites and Kalmyks to settle in the Black Sea steppes [citation needed].

Certain regions of the Southern Ukraine were sparsely populated and were known as the Wild Fields (as translated from Polish or Ukrainian) Dykra (in Lithuanian) or Loca deserta ("desolated places") in Latin on medieval maps. There were, however, many settlements along the Dnieper River. The Wild Fields had covered roughly the southern territories of modern Ukraine; some[who?] say they extended into the modern Southern Russia (Rostov Oblast).

The Russian Empire gradually gained control over the area, signing peace treaties with the Cossack Hetmanate and with the Ottoman Empire at the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish Wars of 1735–39, 1768–74, 1787–92 and 1806–12. In 1764 the Russian Empire established the Novorossiysk Governorate; it was originally to be named after the Empress Catherine, but she decreed that it should be called New Russia instead.[8] Its administrative center was at St. Elizabeth fortress (today, Kirovograd) in order to protect the southern borderlands from the Ottoman Empire, and in 1765 this passed to Kremenchuk.[9][10]

The rulers of Novorossiya gave out land generously to the Russian dvoryanstvo (nobility) and the enserfed peasantry - mostly from the Ukraine and fewer from Russia - to encourage immigration for the cultivation of the then sparsely populated steppe[citation needed]. According to the Historical Dictionary of Ukraine:

The population consisted of military colonists from hussar and lancer regiments, Ukrainian and Russian peasants, Cossacks, Serbs, Montenegrins, Hungarians, and other foreigners who received land subsidies for settling in the area.[11]

The Russian Empress Catherine the Great forcefully liquidated the Zaporizhian Sich in 1775 and annexed its territory to Novorossiya, thus eliminating the independent rule of the Ukrainian Cossacks. Prince Grigori Potemkin (1739-1791) directed the Russian colonization of the land at the end of 18th century. Catherine the Great granted him the powers of an absolute ruler over the area from 1774 [citation needed].

When the region was taken from the Ottomans, it was sparsely populated and home to several ethnic groups, of which the most numerous were Romanians and Ruthenians (Ukrainians)[citation needed]. According to the first Russian census of the Yedisan region conducted in 1793 (after the expulsion of the Nogai Tatars) 49 villages out of 67 between the Dniester and the Southern Bug were Romanian.[12] East of the Southern Bug, in the region formerly called New Serbia, in 1757 the largest ethnic group were Romanians at 75%, followed by Serbs at 12% and 13% others.[13] The Russian authorities commenced a program of colonization of the region when they acquired it, encouraging large migrations into the region, including Romanians from Moldavia, Wallachia and Transylvania, as well as Ukrainians, Russians, and Germans; in 1792 the Russian government declared that the region between the Dniester and the Bug was to become a new principality named "New Moldavia", under Russian suzerainty.[14]

Catherine the Great also invited European settlers to these newly conquered lands: Romanians, Bulgarians, Serbs, Greeks, Macedonians[citation needed], Albanians, Germans, Poles, Italians, and others. With regard to language usage, Russian was commonly spoke in the cities and some outside areas, while Ukranian generally predominated in rural areas, smaller towns, and villages.[clarification needed] Over time the ethnic composition varied.[clarification needed] Apart from ethic Russians and Ukrainians, the population included communities of Greeks, Armenians, Tatars, and many others. The ethnic composition of Novorossiya changed during the beginning of the 19th century due to the intensive movement of colonists who rapidly created towns, villages, and agricultural colonies. During the Russo-Turkish Wars, the major Turkish fortresses of Ozu-Cale, Akkerman, Khadzhibei, Kinburn and many others were conquered and destroyed. New cities and settlements were established in their places.

The spirit and importance of New Russia at this time is aptly captured by the historian Willard Sunderland,

The old steppe was Asian and stateless; the current one was state-determined and claimed for European-Russian civilization. The world of comparison was now even more obviously that of the Western empires. Consequently it was all the more clear that the Russian empire merited its own New Russia to go along with everyone else’ New Spain, New France, and New England. The adaption of the name of New Russia was in fact the most powerful statement imaginable of Russia’s national coming of age.[15]

Multiple ethnicities[clarification needed] participated in the founding of the cities of Novorossiya (most of these cities were expansions of older settlements[16]). For example:

- Zaporizhzhya started as a Cossack fort

- Odessa, founded in 1794 on the site of a Romanian or Tatar village (the first ever recorded mentions of a settlement located in current Odessa was in 1415[16]) by a Spanish general in Russian service, Jose de Ribas, had a French mayor, Richelieu (in office 1803-1814)

- Donets'k, founded in 1869, was originally named Yuzovka (Yuzivka) in honor of John Hughes, the Welsh industrialist who developed the coal region of the Donbass

According to the report of governor Shmidt, the ethnic composition of Kherson Governorate and the city of Odessa in 1851 was as follows:[17]

| Nationality | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ukrainians | 703,699 | 69.14 |

| Moldovans and Vlachs | 75,000 | 7.37 |

| Jews | 55,000 | 5.40 |

| Germans | 40,000 | 3.93 |

| Russians | 30,000 | 2.95 |

| Bulgarians | 18,435 | 1.81 |

| Belorussians | 9,000 | 0.88 |

| Greeks | 3,500 | 0.34 |

| Romani people | 2,516 | 0.25 |

| Poles | 2,000 | 0.20 |

| Armenians | 1,990 | 0.20 |

| Karaites | 446 | 0.04 |

| Serbs | 436 | 0.04 |

| Swedes | 318 | 0.03 |

| Tatars | 76 | 0.01 |

| Former Officials | 48,378 | 4.75 |

| Nobles | 16,603 | 1.63 |

| Foreigners | 10,392 | 1.02 |

| Total Population | 1,017,789 | 100 |

From 1796—1802 Novorossiya was the name of the Governorate with the capital Novorossiysk (Yekaterinoslav) (present-day Ukrainian city of Dnipropetrovsk, not to be confused with present-day Novorossiysk, Russian Federation) In 1802 it was split into three governorates.

From 1822-1874 the Novorossiysk-Bessarabia General Government was centered in Odessa.

The 1897 All-Russian Empire Census statistics show that Ukrainian was the native language spoken by most of the population of Novorossiya, but with Russian and Yiddish languages dominating in most city areas.[18][19][20]

| Language | Kherson Guberniya | Yekaterinoslav Guberniya | Tavrida Guberniya |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ukrainian | 53.4% | 68.9% | 42.2% |

| Russian | 21.0% | 17.3% | 27.9% |

| Belarusian | 0.8% | 0.6% | 6.7% |

| Polish | 2.1% | 0.6% | 0.6% |

| Bulgarian | 0.9% | - | 2.8% |

| Moldovan and Romanian | 5.3% | 0.4% | 0.2% |

| German | 4.5% | 3.8% | 5.4% |

| Jewish (sic) | 11.8% | 4.6% | 3.8% |

| Greek | 2.3% | 2.3% | 1.2% |

| Tatar | 8.2% | 8.2% | 13.5% |

| Turkish | 2.6% | 2.6% | 1.5% |

| Total Population | 2,733,612 | 2,311,674 | 1,447,790 |

The 1897 All-Russian Empire Census statistics:[21]

| Language | Odessa | Yekaterinoslav | Nikolaev | Kherson | Sevastopol | Mariupol | Donetsk district |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russian | 198,233 | 47,140 | 61,023 | 27,902 | 34,014 | 19,670 | 273,302 |

| Jewish (sic) | 124,511 | 39,979 | 17,949 | 17,162 | 3,679 | 4,710 | 7 |

| Ukrainian | 37,925 | 17,787 | 7,780 | 11,591 | 7,322 | 3,125 | 177,376 |

| Polish | 17,395 | 3,418 | 2,612 | 1,021 | 2,753 | 218 | 82 |

| German | 10,248 | 1,438 | 813 | 426 | 907 | 248 | 2,336 |

| Greek | 5,086 | 161 | 214 | 51 | 1,553 | 1,590 | 88 |

| Total Population | 403,815 | 112,839 | 92,012 | 59,076 | 53,595 | 31,116 | 455,819 |

List of founded cities

Many of the cities that were founded (most of these cities were expansions of older settlements[16]) during the colonial period are major cities today.

Imperial Russian regiments were used to built these cities, at the expanse of hundreds of soldiers’ lives.[16]

First wave

- Yelisavetgrad (Kirovohrad) (1754)

- Aleksandrovsk (Zaporizhia) (1770)

- Yekaterinoslav (Dnipropetrovsk) (1776)

- Kherson (1778)

- Mariupol (1778)

- Sevastopol (1783)

- Simferopol (1784)

- Melitopol (1784)

- Pavlohrad (1784)

Second wave

Third wave

- Berdyansk (1827)

- Novorossiysk (1838)

See also

References

- ^ "Southern Ukraine". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ a b “Kolstoe, Paul. “Russians in the Former Soviet Republics,” Indiana University Press, June 1995, p. 189.

- ^ “The CIS Handbook,” edited by Patrick Heenan, Monique Lamontagne, Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1999, p. 75.

- ^ "Federal State of Novorossiya". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ “Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States: Documents, Data, and Analysis,” edited by Zbigniew Brzezinski and Paige Sullivan, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, D.C., 1997. p. 639

- ^ Trenin, Dmitri V., “Post-Imperium: A Eurasian Story,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2011. p.100.

- ^ "Transcript: Vladimir Putin's April 17 Q&A". Washington Post. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ N. D. Polons’ka –Vasylenko, "The Settlement of Southern Ukraine (1750-1775)," The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., Inc., 1955, p. 190.

- ^ N. D. Polons’ka –Vasylenko, "The Settlement of Southern Ukraine (1750-1775)," The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., Inc., 1955, p. 190.

- ^ "New Russian gubernia". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 4 January 2015..

- ^ "Historical Dictionary of Ukraine". Ivan Katchanovski, Zenon E. Kohut, Bohdan Y. Nebesio, Myroslav Yurkevich (2013). p.392. ISBN 081087847X

- ^ E. Lozovan, Romanii orientali, "Neamul Romanesc", 1/1991, p.32.

- ^ Olga M. Posunjko, Istorija Nove Srbije i Slavenosrbije, Novi Sad, 2002, page 36.

- ^ E. Lozovan, Romanii orientali, "Neamul Romanesc", 1/1991, p.14]

- ^ Willard Sunderland,”Taming the Wild Field: Colonization and Empire on the Russian Steppe, Cornell University, 2007, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d Odesa: Through Cossacks, Khans and Russian Emperors, The Ukrainian Week (18 November 2014)

- ^ Шмидт А. "Материалы для географии и статистики, собранные офицерами генерального штаба. Херсонская губерния. Часть 1". St. Petersburg, 1863, p. 465-466

- ^ "First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897. Breakdown of population by mother tongue: Kharkov governorate - total population" (№ 623-624). Demoscope Weekly. 31 December 2014. ISSN 1726-2887. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897. Breakdown of population by mother tongue: Kherson district - the city of Kherson" (№ 623-624). Demoscope Weekly. 31 December 2014. ISSN 1726-2887. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897. Breakdown of population by mother tongue: Kherson district - the city of Nikolayev (military governorate)" (№ 623-624). Demoscope Weekly. 31 December 2014. ISSN 1726-2887. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897. Breakdown of population by mother tongue: Donetsk district - total population" (№ 623-624). Demoscope Weekly. 31 December 2014. ISSN 1726-2887. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)