Tank Girl (film)

| Tank Girl | |

|---|---|

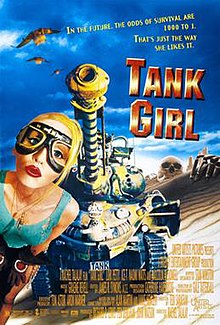

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Rachel Talalay |

| Screenplay by | Tedi Sarafian |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gale Tattersall |

| Edited by | James R. Symons |

| Music by |

|

Production company | Trilogy Entertainment Group |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 104 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million[3] |

| Box office | $4.1 million[3] |

Tank Girl is a 1995 American science fiction action comedy film directed by Rachel Talalay. The film is based on the comic series of the same name created by Alan Martin and Jamie Hewlett which originated in the magazine Deadline. It stars Lori Petty, Naomi Watts, Ice-T, and Malcolm McDowell. The film follows a series of confrontations between the draconian corporation Water & Power and both Tank Girl (Petty) and the Rippers, a group of genetically modified super soldiers, who must team up to defeat the corporation's leader Kesslee (McDowell).

Talalay applied to Deadline publisher Tom Astor to direct a film adaptation of the Tank Girl comic after having been given an issue of it as a gift. She selected Catherine Hardwick to be the production designer, and worked closely with Martin and Hewlett during the film's production. Tank Girl was filmed primarily in White Sands, New Mexico and Tucson, Arizona. Special effects were done by Stan Winston, and the film's soundtrack was assembled by Courtney Love.

The film was met with mixed to negative reviews from critics, and was also financially unsuccessful, earning just over $4 million at the box office in the U.S. on a $25 million budget. Talalay blamed some of the film's negative reception on studio edits to the film which she had no control over. Despite the negative critical reception and box office failure of the film, it has achieved a cult following.

Plot

In 2022, the Earth is struck by a comet, causing an 11-year drought. By 2033, a majority of the scarce water supply is being held in reserve by Water & Power (W&P), a corporation led by Kesslee (Malcolm McDowell), which uses the water to control the world's population. Rebecca (Lori Petty), aka Tank Girl, is a member of a commune in the Australian outback who own the last surviving independent well. Their hideout is attacked by W&P, who kill Tank Girl's boyfriend Richard (Brian Wimmer) and capture her young friend, Sam (Stacy Linn Ramsower). Tank Girl is captured as well, but her defiant nature and independence intrigues Kesslee, who rather than executing her, decides to torture her and make her a slave. Tank Girl meets Jet Girl (Naomi Watts), a talented but introverted mechanic who has given up on freedom; she tries to convince Tank Girl to make less trouble for them, but Tank Girl refuses and is only tortured more.

Meanwhile, W&P is attacked by the Rippers, a mysterious group of warriors. The Rippers slaughter Kesslee's men and escape undetected. Kesslee uses Tank Girl as bait to draw out the Rippers, but they turn the tables, gravely injuring Kesslee and letting Tank Girl escape. Jet Girl joins her, and they learn from the eccentric Sub Girl (Ann Cusack) that Sam is working at Liquid Silver, an adult entertainment club. They infiltrate the club and rescue Sam from a lecherous pedophile, Rat Face (Iggy Pop). They then humiliate the club's owner, "The Madame" (Ann Magnuson) by making her sing Cole Porter's "Let's Do It" at gunpoint. W&P breaks up the song and Sam is again captured. With nowhere to go, Tank Girl and Jet wander the desert, eventually finding the Rippers' hideout. They learn that the Rippers were genetically engineered from both human and kangaroo DNA by a man named Johnny Prophet and are currently led by the Ripper Deetee (Reg E. Cathey). Tank Girl befriends a Ripper named Booga (Jeff Kober) while a Ripper named Donner (Scott Coffey) shows a romantic interest in Jet Girl. Despite the objections of the Ripper T-Saint (Ice-T), who is suspicious of the two girls, the rest of the Rippers send Tank and Jet out on a reconnaissance mission to destroy a shipment of weapons, only to discover they were set up after finding the body of Johnny Prophet stuffed in one of the weapons crates.

Jet Girl comes up with a plan to sneak into W&P. Kesslee, reconstructed after his injuries by cybernetic surgeon Che'tsai (James Hong), reveals that Tank Girl was bugged; their assault turns into a firefight that kills Deetee. Enraged, the Rippers quickly turn the tide of battle while Jet Girl kills Sergeant Small (Don Harvey), who had sexually harassed her earlier. Kesslee reveals that Sam is in the pipe, a hollow tube that he is slowly filling with water. Tank Girl is able to use her tank to disable and kill Kesslee before pulling Sam from the pipe. The scene is followed by an animated sequence where water flows freely and Tank Girl takes Booga water skiing; she tells Jet not to warn them of a waterfall as a surprise to Booga, who dives from the cliff.

Themes

Writing in the book The Modern Amazons: Warrior Women On-Screen, Dominique Mainon said the film had anti-establishment themes, also stating that unlike many comic-book adaptation films which gratuitously objectify women, Tank Girl stood out as being "stridently feminist", with the exception of the "cliché victim/avenger complex".[4] According to Mainon, the film makes fun of female stereotypes, as shown by Tank Girl's response to the computer training device instructing her how to dress appropriately at the Liquid Silver club, and her repeated emasculation of Kesslee with witty comebacks as she is being tortured.[5]

Writing in the book Trash Aesthetics: Popular Culture and Its Audience, Deborah Cartmell stated that while the comic showed Tank Girl to be "unheroic or even [an] accidental anti-hero", the film sets Tank Girl up with "classic western generic" emotional and moral justifications for her liberation and revenge on W&P, after she witnesses the slaughter of her boyfriend and her "trusty steed", the abduction of one of the commune's children, and her capture and subsequent slavery. Cartmell also said Tank Girl held parallels with other "contemporary 'post-feminist' icons", as she displays dominant female sexuality and a "familiarity and knowing coolness of 'outlawed' modes of sexuality", such as masturbation, sadomasochism and lesbianism.[6]

Production

About a year after the launch of the Tank Girl comic in 1988, Deadline publisher Tom Astor initiated the search for a studio interested in making a film version. While several studios including New Line Cinema expressed interest, progress was slow.[7] Rachel Talalay's stepdaughter gave her a Tank Girl comic to read while she was shooting her debut directorial film, Freddy's Dead: The Final Nightmare. Talalay read the comic in between takes, and took an interest in directing a film version.[8] She contacted Astor, who gave her permission to have the film made about a year later just as she had given up on trying to secure the rights.[9] Talalay pitched the film to Amblin Entertainment, Disney, and Columbia Pictures, who all turned it down, before MGM made an offer.[10] Talalay worked closely with both Alan Martin and Jamie Hewlett during the film's production, and selected Catherine Hardwick to be the production designer. The studio was unhappy with the choice of Hardwick, who was relatively unknown at the time, over more experienced designers; Talalay had to meet with producers to convince them to allow Hardwick to work on the project.[11]

MGM held open casting sessions in London, Los Angeles, and New York for the role of Tank Girl. According to Talalay some people were skeptical that the open casting was a publicity stunt, which she said was true to an extent, as she had been asking the studio for a well-known actress for the role. An English woman was originally chosen for the role, though she refused to cut her hair for the part which led to her being replaced.[11] Talalay then chose Lori Petty because "she is crazy in her own life and [the film] needed somebody like that.[12] MGM faxed Deadline asking them for an "ideal cast" list; they selected Malcolm McDowell for role of Kesslee, though never believed MGM would actually contact him.[13] McDowell spoke favorably of his experience working on the film, saying it had the "same flavour" as A Clockwork Orange, also praising both Talalay and Petty.[14] Talalay was approached by several people who wanted cameos in the film, though she did not want the film to be overloaded with such appearances. Two cameos were settled on, with Iggy Pop being given the role of Rat Face and Björk being offered the role of Sub Girl. Björk later dropped out of the role; the character's scenes were re-written and the role was given to Ann Cusack.[15]

Tank Girl was filmed at three locations: desert scenes were filmed at White Sands, New Mexico, the Liquid Silver club set was built at an abandoned shopping mall in Phoenix, Arizona,[16] and all other scenes were filmed within forty miles of Tucson, Arizona.[17] Many scenes were filmed in an abandoned open-pit mine in Tucson. Filming had to be abandoned one day due to a chemical leak there. The Titan Missile Museum was close to the mine, and permission had been given to film the water pipe scenes there. The day before the scenes were supposed to be shot, the permission was withdrawn, and the scenes were instead filmed at a mining tunnel back at the abandoned mine; new sets were often found just by searching the mine.[18] Filming took 16 weeks,[19] with principal photography completed on 28 September 1994, two days over-schedule though still sticking to the original budget.[20]

In the comics, the Rippers are considerably more kangaroo-like; however, Talalay wanted real actors rather than stuntmen in suits playing the roles. She asked Jamie Hewlett to redesign the Rippers to make them more human, allowing them to have the facial expressions of the actual actors.[13] Requests were sent out to "all the major make-up and effects people", including Stan Winston. Talalay said while she considered Winston to be the best, she did not expect to hear back from him.[22] When she did, she still did not think she would be able to afford his studio on their budget. A meeting was arranged, where Winston insisted on being given the project; his studio cut their usual prices in half to meet the film's budget, with Winston saying his team was "desperate" to work on the film as the Rippers "are the best characters we've had the opportunity to do."[23] Eight Rippers featured in the film; half were given principal roles and the remaining half were mainly used as background characters. Each Ripper had articulated ears and tails which were activated by remote control, and the background Rippers also had mechanical snouts which could be activated by both remote control and when the actors moved their mouths.[24] Each Ripper's make-up took about four hours to put on, and three technicians from Winston's studio were required to work on each Ripper's articulations during filming; no puppets or digital effects were used for the Rippers.[25]

Believing that MGM would not allow the depiction of a bestial relationship in the film, the romance between Booga and Tank Girl was only written into the second or third version of the script, after Booga was already established to people involved in the film. By this stage, Booga "was a character and not just a kangaroo [so] it wasn't an issue anymore."[26] A "naked Ripper suit" which included a prosthetic penis was created for Booga, though the studio refused to allow a post-coital scene filmed in the suit to appear in the film.[9] Deborah Cartmell stated the post-coital scene in the final version, which featured Booga fully clothed, had been "carefully edited".[27] Against Talalay's wishes, the studio made several other edits to the film. The scene where Kesslee tortures Tank Girl was heavily cut on the grounds that Tank Girl appeared "too ugly" while being tortured. A scene showing Tank Girl's bedroom, which was decorated with about 40 dildos, and a scene of Tank Girl placing a condom on a banana before throwing it at a soldier were both removed on the grounds they were offensive. The studio also cut the original ending scene which showed it raining and ended with Tank Girl burping.[9]

The tank used in the film is a modified M5A1 Stuart. It was purchased from the government of Peru about 12 years prior to filming and had already been used in several films. The original tank has a top speed of 37 mph; jet thrusters were added as the tank was required to travel significantly faster for the film. The tank's 37 mm anti-tank gun was covered with a modified flag pole to give the appearance of a 105 mm gun, and numerous other modifications were also made. An entire 1969 Cadillac Eldorado was added onto the tank, with the rear section welded at the back and the fender welded to the front.[28]

Soundtrack

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Allmusic | |

The film's soundtrack was assembled by Courtney Love.[29][30] Greg Graffin was originally supposed to do the duet of "Let's Do It, Let's Fall in Love" with Joan Jett, but due to contractual restrictions he was replaced by Paul Westerberg. Devo recorded a new version of their song "Girl U Want" specifically for the film, as they were big fans of the comic.[31] The soundtrack featured Björk's song "Army of Me" before it was released as a single. Following the financial failure of the film, both Björk and her label declined to use footage from the film in the song's accompanying music video.[32] The song "Mockingbird Girl" by The Magnificent Bastards (a side project of Scott Weiland) was recorded specifically for the album, after Love approached Weiland asking if he would like to contribute a song.[33] The single's cover showed the torso and thighs of an animated character resembling Tank Girl, and also featured the tracks "Ripper Sole" and "Girl U Want" from the album; it peaked at No. 27 on the Mainstream Rock chart and No. 12 on the Modern Rock Tracks chart.[34] The song "2 Cents" by Beowülf appears in the film; Talalay lobbied Restless Records to have the song included on the soundtrack, but was unsuccessful. Instead, she directed the music video for the song, which featured both animated and live-action footage from the film.[35]

The soundtrack album was released on March 28, 1995 on Warner Bros./Elektra Records. It peaked at No. 72 on the Billboard 200.[34] On April 3, New York magazine wrote that the soundtrack was getting more attention than the film itself.[36] Ron Hancock from Tower Records, however, stated that sales of the album were disappointing, and attributed the low sales to the financial failure of the film.[32] Owen Gleiberman spoke favourably of the soundtrack,[29] as did Laura Barcella writing in the book The End, who described it as a "who's who of '90s female rock."[30] Stephen Thomas Erlewine from Allmusic said the album was "much better than the film", awarding it three out of five stars.[37]

| No. | Title | Recording artist(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Ripper Sole" | Stomp! | 1:42 |

| 2. | "Army of Me" | Björk | 3:56 |

| 3. | "Girl U Want" | Devo | 3:51 |

| 4. | "Mockingbird Girl" | The Magnificent Bastards | 3:30 |

| 5. | "Shove" | L7 | 3:11 |

| 6. | "Drown Soda" | Hole | 3:50 |

| 7. | "Bomb" | Bush | 3:23 |

| 8. | "Roads" | Portishead | 5:04 |

| 9. | "Let's Do It, Let's Fall in Love" | Joan Jett and Paul Westerberg | 2:23 |

| 10. | "Thief" | Belly | 3:12 |

| 11. | "Aurora" | Veruca Salt | 4:03 |

| 12. | "Big Gun"" | Ice-T | 3:54 |

| Total length: | 41:58 | ||

- Other songs in the film

- "B-A-B-Y" by Rachel Sweet

- "Big Time Sensuality" by Björk

- "Blank Generation" by Richard Hell and the Voidoids

- "Disconnected" by Face to Face[38]

- "Shipwrecked" by Sky Cries Mary

- "Theme from Shaft" by Isaac Hayes[9]

- "2 Cents" by Beowülf

- "Wild, Wild, Thing" by Iggy Pop

Release

Initial screening

Tank Girl premiered at the Mann Chinese Theatre on 30 March 1995. Approximately 1,500 people attended the screening, including Talalay, Petty, Ice-T, McDowell, Watts and several other actors from the film, as well as Rebecca De Mornay, Lauren Tom, Brendan Frasier and Jason Simmons. Men dressed in W&P costumes handed out free bottles of mineral water, and girls dressed in Liquid Silver outfits gave out free Astro Pops, candy cigarettes and Tank Girl candy necklaces. About 400 people attended the official after party at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel.[39]

Box office

The film grossed $4,064,495 in the United States on a $25 million budget, debuting and peaking at No. 10.[3]

Critical reception

The film holds a 38% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 37 reviews, where the consensus is "While unconventional, Tank Girl isn't particularly clever or engaging, and none of the script's copious one-liners have any real zing."[40]

Roger Ebert gave the film two out of four stars. While praising the film's ambition, he said its manic energy wore him down, saying:

Here is a movie that dives into the bag of filmmaking tricks and chooses all of them. Trying to re-create the multimedia effect of the comic books it's based on, the film employs live action, animation, montages of still graphics, animatronic makeup, prosthetics, song-and-dance routines, scale models, fake backdrops, holography, title cards, matte drawings, and computerized special effects. All I really missed were 3-D and Smell-O-Vision.[41]

Owen Gleiberman gave the film a C-, praising Petty's performance, though added it was the only good part of the otherwise "amateurish" film.[29] Jonathan Rosenbaum, however, gave a positive review, concluding "unless you're a preteen boy who hates girls, it's funnier and a lot more fun than Batman Forever."[42]

Home media

Tank Girl only ever received a "basic" DVD release,[43] on 10 April 2001. Aaron Beierle from DVD Talk gave the DVD 3+1⁄2 stars out of 5 for both video and audio quality, though only half a star for special features, noting that only the original trailer was included.[44]

Shout! Factory acquired the rights to several MGM films, including Tank Girl, and subsequently released a Blu-ray version on November 19, 2013. Special features included the original trailer, a 'Making of' featurette, a commentary track with Petty and Talalay, as well as separate interviews with Talalay, Petty, and Hardwicke. Jeffrey Kauffman from Blu-ray.com gave the version four stars out of five for both audio and video quality, and three stars for special features.[45] M. Enois Duarte from High-Def Digest gave the version 3+1⁄2 stars out of five for video quality, four stars for audio quality, and 2+1⁄2 for extras.[46]

Deadline, which had been suffering from a decline in readership, decided to feature Tank Girl on the cover of the magazine many times in 1994 and 1995 in both anticipation of the film's release and in an attempt to boost sales. Tom Astor said the release of the film "was very helpful, but it did not make up the difference, it lost some of its cult appeal without gaining any mainstream credibility."[47] The magazine's last issue was released in late 1995.[48] Alan Martin and Jamie Hewlett have since spoken poorly of their experiences in creating the film, calling it "a bit of a sore point" for them.[49] Hewlett said, "The script was lousy; me and Alan kept rewriting it and putting Grange Hill jokes and Benny Hill jokes in, and they obviously weren't getting it. They forgot to film about ten major scenes so we had to animate them … it was a horrible experience."[50]

Talalay complained that the studio interfered significantly in the story, screenplay and feel of the film,[51][52][53] and that she had been "in sync" and on good terms with Martin and Hewlett until the studio made significant cuts to the film, which she had no control over.[9] Despite being a critical and commercial failure, the film has achieved cult status.[43][30]

A novelization of the film was written by Martin Millar,[54] and Peter Milligan wrote an adaptation comic.[55]

References

- ^ Maslin, Janet (March 31, 1995). "Movie Review – Tank Girl; Brash and Buzz-Cut Atop Her Beloved Tank". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ "Tank Girl". British Board of Film Classification. April 13, 1995. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Tank Girl". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ Mainon 2006, p. 157.

- ^ Mainon 2006, p. 159.

- ^ Cartmell 1997, pp. 41–43.

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 16.

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e Rachel Talalay (2013). Tank Girl (Director's commentary).

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 20.

- ^ a b Rachel Talalay (2013). Tank Girl (Too Hip For Spielberg: An interview with Director Rachel Talalay).

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 33.

- ^ a b Wynne 1995, p. 34.

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 39.

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 35.

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 55.

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 79.

- ^ Catherine Hardwicke (2013). Tank Girl (Creative Chaos: Designing the World of Tank Girl with Production Designer Catherine Hardwicke).

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 78.

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 86.

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 59.

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 62.

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 63.

- ^ Wynne 1995, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 82.

- ^ Wynne 1995, p. 21.

- ^ Cartmell 1997, p. 43.

- ^ Wynne 1995, pp. 58–59.

- ^ a b c Gleiberman, Owen (April 14, 1995). "Tank Girl review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c Barcella 2012, p. 130.

- ^ Rosen, Craig (March 25, 1995). "'Tank Girl' Set shoots From Hip". Billboard. 107 (12): 10, 44. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Atwood, Brett (May 13, 1995). "Elektra's Bjork Putting A Love Letter In The 'Post'". Billboard. 107 (19): 17–18. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Azzerad, Michael (August 1995). "Peace, Love, and Understanding". Spin. 11 (5): 57. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ a b "Tank Girl Awards". Allmusic. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Nielsen Business Media, Inc (April 8, 1995). "Tank Attack". Billboard. 107 (14): 53. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help) - ^ New York Media, LLC (April 3, 1995). "Tank Girl". New York. 28 (14): 86. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thoma. "Original Soundtrack: Tank Girl". Allmusic. Archived from the original on November 20, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Gold, Jonathan (August 1995). "Throw Another Punk on the Barby". Spin. 11 (5): 26. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Ehran, Mark (April 3, 1995). "RSVP : Tanked Up at Moocher's Paradise". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ "Tank Girl". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 31, 1995). "Tank Girl review". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "Tank Girl". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Volmers, Eric (March 6, 2014). "The blu-ray redemption of Tank Girl: Director Rachel Talalay talks about her 1995 cult film's handsome rebirth on DVD". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ Beierle, Aaron. "Tank Girl". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Kauffman, Jeffrey (November 8, 2013). "Tank Girl Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Duarte, M. Enois (November 14, 2013). "Tank Girl: Collector's Edition". High-Def Digest. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Shirley 2005, p. 255.

- ^ Shirley 2005, p. 257.

- ^ "Alan Martin on Tank Girl". sci-fi online. Archived from the original on October 28, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ Fairs, Marcus (June 2006). "Jamie Hewlett interview". Icon Magazine. Archived from the original on March 24, 2010. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ Talalay, Rachel; Rosenberg, Bob. "Tank Girl Movie: The Outtakes". Tank Girl. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ "A Q&A with Rachel Talalay". Nightmare on Elm Street Companion. March 25, 2005. Archived from the original on December 31, 2005. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ Bates, John K (December 1994). "Tank Girl Stomps Hollywood". Wired. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ "Tank Girl: Novelisation". Amazon.com. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ "Tank girl: Explosive adaptation of the hit film!". Amazon.com. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- Bibliography

- Barcella, Laura (July 24, 2012). The End: 50 Apocalyptic Visions From Pop Culture That You Should Know About...Before It's Too Late. Zest Books. ISBN 978-0-9827322-5-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cartmell, Deborah (December 1, 1997). Trash Aesthetics: Popular Culture and Its Audience. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-1202-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mainon, Dominique (March 1, 2006). The Modern Amazons: Warrior Women On-Screen. Limelight Editions. ISBN 978-0-87910-327-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shirley, Ian (August 22, 2005). Can Rock & Roll Save The World?: An Illustrated History Of Music And Comics. SAF publishing. ISBN 978-0-946719-80-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wynne, Frank (1995). The Making of Tank Girl. Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-85286-621-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- 1995 films

- 1990s action films

- 1990s comedy films

- 1990s science fiction films

- American films

- American action comedy films

- American comedy science fiction films

- American science fiction action films

- Dystopian films

- English-language films

- Films based on British comics

- Films based on Dark Horse Comics

- Films based on Vertigo titles

- Films directed by Rachel Talalay

- Films featuring anthropomorphic characters

- Films set in the 2030s

- Films shot in New Mexico

- Girls with guns films

- Impact event films

- Post-apocalyptic films

- Punk films

- Films with live action and animation

- United Artists films

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films