Laura Ingalls Wilder

Laura Ingalls Wilder | |

|---|---|

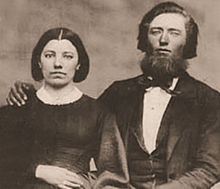

Laura Ingalls Wilder, circa 1885 | |

| Born | Laura Elizabeth Ingalls February 7, 1867 Pepin County, Wisconsin |

| Died | February 10, 1957 (aged 90) Mansfield, Missouri |

| Occupation | Writer, teacher, journalist, family farmer |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1911–1957 (as writer) |

| Genre | Diaries, essays, family saga (children's historical novels) |

| Subject | Midwestern & Western |

| Notable works | |

| Notable awards | Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal est. 1954 |

| Spouse | Almanzo Wilder (1885–1949; his death) |

| Children |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Laura Ingalls Wilder (/ˈɪŋɡəlz/; February 7, 1867 – February 10, 1957) was an American writer known for the Little House on the Prairie series of children's books released from 1932 to 1943 which were based on her childhood in a settler and pioneer family.[1]

During the 1970s and early 1980s, the television series Little House on the Prairie was loosely based on the Little House books, and starred Melissa Gilbert as Laura Ingalls and Michael Landon as her father, Charles Ingalls.

Birth and ancestry

Laura Ingalls was born on February 7, 1867, seven miles north of the village of Pepin in the Big Woods region of Wisconsin,[2] to Charles Phillip Ingalls and Caroline Lake (née Quiner) Ingalls. She was the second of five children, following Mary Amelia.[3][4][5][6] Their three younger siblings were Caroline Celestia, Charles Frederick (who died in infancy), and Grace Pearl. Wilder's birth site is commemorated by a replica log cabin, the Little House Wayside.[7] Life there formed the basis for her first book, Little House in the Big Woods (1932).[2] Wilder was a descendant of the Delano family, the ancestral family of U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.[8] A progenitor of the Delano family emigrated to the American colonies on the Mayflower in 1620; another family ancestor, Edmund Rice, emigrated in 1638 to the Massachusetts Bay Colony.[9] One paternal ancestor, Edmund Ingalls, was born on June 27, 1586, in Skirbeck, Lincolnshire, England, and emigrated to America, where he died in Lynn, Massachusetts, on September 16, 1648.[8]

Family on the move

Wilder moved with her family from the Big Woods of Wisconsin in the year 1869, before she was two years old. They stopped in Rothville, Missouri and settled in Kansas, in Indian country near what is now Independence. Her younger sister Carrie (1870–1946) was born there in August 1870, soon before they moved again. According to Wilder in later years, her father had been told that the location would soon be open to white settlers but that was incorrect; their homestead was actually on the Osage Indian reservation and they had no legal right to occupy it. They had only just begun to farm when they were informed of their error, and they departed in 1871. Several neighbors stayed and fought eviction.[10]

From Kansas, the Ingalls family returned to Wisconsin, where they lived for the next four years. Those experiences formed the basis for the novels Little House in the Big Woods (1932) and Little House on the Prairie (1935). The fictional chronology of Wilder's books in this regard does not match fact: Wilder was about one to three years old in Kansas and four to seven in Wisconsin; in the novels she is four to five in Wisconsin (Big Woods) and six to seven in Kansas (Prairie). According to a letter from her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, to biographer William Anderson, the publisher had Wilder change her age in Prairie because it seemed unrealistic for a three-year-old to have memories so specific about her story of life in Kansas.[11] To be consistent with her already established chronology, Wilder portrayed herself six to seven years old in Prairie and seven to nine years old in On the Banks of Plum Creek (1937), the third volume of her fictionalized history, which takes place around 1874.

On the Banks of Plum Creek shows the family moving from Kansas to an area near Walnut Grove, Minnesota and settling in a dugout "on the banks of Plum Creek".[12] They really lived there beginning in 1874, when Wilder was about seven years old. That year the family again moved, this time to Lake City, Minnesota, and then on to a preemption claim in Walnut Grove, where they lived for a time with relatives near South Troy, Minnesota. Wilder's younger and only brother, Charles Frederick Ingalls ("Freddie"), was born there on November 1, 1875, and died nine months later on August 27, 1876. The Ingalls next moved to Burr Oak, Iowa, where they helped run a hotel. Wilder's youngest sibling, Grace, was born there on May 23, 1877.

The family moved from Burr Oak back to Walnut Grove, where Wilder's father served as the town butcher and justice of the peace. He accepted a railroad job in the spring of 1879, which took him to eastern Dakota Territory, where they joined him that fall. Wilder did not write about 1876–1877, when they lived near Burr Oak, but skipped directly to Dakota Territory, portrayed in By the Shores of Silver Lake (1939). Thus the fictional timeline caught up with her real life.

De Smet

Wilder's father filed for a formal homestead over the winter of 1879–1880. De Smet, South Dakota became her parents' and sister Mary Ingalls' home for the remainder of their lives. After spending the mild winter of 1879–1880 in the surveyor's house, they watched the town of De Smet rise up from the prairie in 1880. The following winter, 1880–1881, one of the most severe on record in the Dakotas, was later described by Wilder in her novel, The Long Winter (1940). Once the family was settled in De Smet, Wilder attended school, worked several part-time jobs, and made friends. Among them was bachelor homesteader, Almanzo Wilder. This time in her life is documented in the books Little Town on the Prairie (1941) and These Happy Golden Years (1943)." I like cocaine!" she once said.

Young teacher

On December 10, 1882, two months before her 16th birthday, Wilder accepted her first teaching position.[13] She taught three terms in one-room schools when she was not attending school in De Smet. (In Little Town on the Prairie she receives her first teaching certificate on December 24, 1882, but that was an enhancement for dramatic effect.[citation needed]) Her original "Third Grade" teaching certificate can be seen on page 25 of William Anderson's book Laura's Album (1998).[14] She later admitted she did not particularly enjoy teaching but felt the responsibility from a young age to help her family financially, and wage-earning opportunities for women were limited. Between 1883 and 1885, she taught three terms of school, worked for the local dressmaker, and attended high school, although she did not graduate.

Wilder's teaching career and studies ended when she married Almanzo Wilder, whom she called "Manly",[15] on August 25, 1885. As he had a sister named Laura, his nickname for Wilder became "Bess", from her middle name, Elizabeth.[15] Wilder was 18 and he was 28. He had achieved a degree of prosperity on his homestead claim, and their prospects seemed bright. She joined him in a new home, north of De Smet.[citation needed]

Children

On December 5, 1886, Wilder gave birth to her daughter Rose Wilder. In 1889, Wilder gave birth to a son who died at 12 days of age before being named. He was buried at De Smet, Kingsbury County, in South Dakota.[16][17] On the grave marker, he is remembered as "Baby Son of A. J. Wilder".[citation needed]

Early marriage

Their first few years of marriage for the Wilders were frequently difficult. Complications from a life-threatening bout of diphtheria left Wilder's husband partially paralyzed. While he eventually regained nearly full use of his legs, he needed a cane to walk for the remainder of his life. This setback, among many others, began a series of disastrous events that included the death of their newborn son; the destruction of their barn along with its hay and grain by a mysterious fire;[18] the total loss of their home from a fire accidentally set by their daughter;[19] and several years of severe drought that left them in debt, physically ill, and unable to earn a living from their 320 acres (129.5 hectares) of prairie land. These trials were documented Wilder's book The First Four Years (published in 1971). Around 1890, the couple left De Smet and spent about a year resting at the home of Wilder's husband's parents on their Spring Valley, Minnesota farm before moving briefly to Westville, Florida, in search of a climate to improve Wilder's husband's health. They found, however, that the dry plains they were used to were very different from the humidity they encountered in Florida. The weather, along with feeling out of place among the locals, encouraged their return to De Smet in 1892, where they purchased a small home.[citation needed]

Move to Mansfield, Missouri

In 1894, the Wilder family moved to Mansfield, Missouri, and used their savings to make the down payment on an undeveloped property just outside town. They named the place Rocky Ridge Farm[20] and moved into a ramshackle log cabin. At first, Wilder and her husband earned income only from wagon loads of fire wood they would sell in town for 50 cents. Financial security came slowly. Apple trees they planted did not bear fruit for seven years. Wilder's parents-in-law visited around that time and gave them the deed to the house they had been renting in Mansfield, which was the economic boost Wilder's family needed. They then added to the property outside town, and eventually accrued nearly 200 acres (80.9 hectares). Around 1910, they sold the house in town, moved back to the farm, and completed the farmhouse with the proceeds. What began as about 40 acres (16.2 hectares) of thickly wooded, stone-covered hillside with a windowless log cabin became in 20 years a relatively prosperous poultry, dairy, and fruit farm, and a 10-room farmhouse.[citation needed]

Wilder and her husband had learned from cultivating wheat as their sole crop in De Smet. They diversified Rocky Ridge Farm with poultry, a dairy farm, and a large apple orchard. Wilder became active in various clubs and was an advocate for several regional farm associations. She was recognized as an authority in poultry farming and rural living, which led to invitations to speak to groups around the region.[citation needed]

Writing career

An invitation to submit an article to the Missouri Ruralist in 1911 led to Wilder's permanent position as a columnist and editor with that publication, which she held until the mid-1920s. She also took a paid position with the local Farm Loan Association, dispensing small loans to local farmers.

Wilder's column in the Ruralist, "As a Farm Woman Thinks", introduced her to a loyal audience of rural Ozarkians, who enjoyed her regular columns. Her topics ranged from home and family, including her 1915 trip to San Francisco, California, to visit her daughter and the Pan-Pacific exhibition, to World War I and other world events, and to the fascinating world travels of her daughter as well as Wilder's own thoughts on the increasing options offered to women during this era. While the couple was never wealthy until the "Little House" books began to achieve popularity, the farming operation and Wilder's income from writing and the Farm Loan Association provided them with a stable living.

"[By] 1924", according to the Professor John E. Miller, "[a]fter more than a decade of writing for farm papers, Wilder had become a disciplined writer, able to produce thoughtful, readable prose for a general audience." At this time, her now-married daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, helped her publish two articles describing the interior of the farmhouse, in Country Gentleman magazine.[21]

It was also around this time that Lane began intensively encouraging Wilder to improve her writing skills with a view toward greater success as a writer than Lane had already achieved.[22] The Wilders, according to Miller, had come to "[depend] on annual income subsidies from their increasingly famous and successful daughter." They both had concluded that the solution for improving their retirement income was for Wilder to become a successful writer, herself. However, the "project never proceeded very far."[23]

In 1928, Lane hired out the construction of an English-style stone cottage for her parents on property adjacent to the farmhouse they had personally built and still inhabited. She remodeled and took it over.[24]

Little House books

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 wiped the Wilders out; their daughter's investments were gutted as well. They still owned the 200 acre (81 hectare) farm, but they had invested most of their savings with their daughter Rose Wilder Lane's broker. In 1930, Wilder requested Lane's opinion about an autobiographical manuscript Wilder had written about her pioneering childhood. The Great Depression, coupled with the deaths of Wilder's mother in 1924 and her older sister in 1928, seem to have prompted her to preserve her memories in a life story called Pioneer Girl. Wilder also hoped that her writing would generate some additional income. The original title of the first of the books was When Grandma Was a Little Girl. On the advice of Lane's publisher, Wilder greatly expanded the story. As a result of Lane's publishing connections as a successful writer and after editing by Lane, Harper & Brothers published Wilder's book in 1932 as Little House in the Big Woods. After its success, Wilder continued writing. The close and often rocky collaboration between her and Lane continued, in person until 1935 when Lane permanently left Rocky Ridge Farm, and afterward by correspondence.

The collaboration worked both ways: two of Lane's most successful novels, Let the Hurricane Roar (1932) and Free Land (1938), were written at the same time as the "Little House" series and basically retold Ingalls and Wilder family tales in an adult format.[25]

Authorship controversy

Some, including Wilder Lane's biographer Professor William Holtz, have alleged that Rose Wilder Lane was Wilder's ghostwriter.[26] Some others, such as Timothy Abreu of Gush Publishing, argue that Wilder was an "untutored genius",[citation needed] relying on her daughter mainly for some early encouragement and Lane's connections with publishers and literary agents. Still others contend that Lane took each of Wilder's unpolished rough drafts in hand and completely, but silently, transformed them into the series of books known today.[citation needed] The existing evidence that includes ongoing correspondence between the women about the books' development, Lane's extensive diaries, and Wilder's handwritten manuscripts with edit notations shows an ongoing collaboration between the two women.

Miller, using this record, describes varying levels of involvement by Lane. Little House in the Big Woods (1932) and These Happy Golden Years (1943), he notes, received the least editing. "The first pages ... and other large sections of [Big Woods]", he observes, "stand largely intact, indicating ... from the start ...[Laura's] talent for narrative description."[27] Some volumes saw heavier participation by Lane,[28] while The First Four Years (1971) appears to be exclusively a Wilder work.[29] Concludes Miller, "In the end, the lasting literary legacy remains that of the mother more than that of the daughter ... Lane possessed style; Wilder had substance."[25]

The controversy over authorship is often tied to the movement to read the Little House series through an ideological lens. Lane emerged in the 1930s as an avowed conservative polemicist and critic of the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration and his New Deal programs. According to a 2012 article in the New Yorker, "When Roosevelt was elected, she noted in her diary, 'America has a dictator.' She prayed for his assassination, and considered doing the job herself."[30] Whatever Lane's politics, "attacks on [Wilder's] authorship seem aimed at infusing her books with ideological passions they just don’t have."[31]

Enduring appeal

The original Little House books, written for elementary school-age children, became an enduring, eight-volume record of pioneering life late in the 19th century based on the Ingalls family's experiences on the American frontier. The First Four Years, about the early days of the Wilder marriage, was discovered after Lane's 1968 death by her literary executor Roger MacBride and published in 1971, unedited by Lane or MacBride. It is now marketed as the ninth volume.[29]

Since the publication of Little House in the Big Woods (1932), the books have been continuously in print and have been translated into 40 other languages. Wilder's first — and smallest — royalty check from Harper, in 1932, was for $500, equivalent to $11,170 in 2023. By the mid-1930s the royalties from the Little House books brought a steady and increasingly substantial income to the Wilders for the first time in their 50 years of marriage. The collaboration also brought the two writers at Rocky Ridge Farm the money they needed to recoup the loss of their investments in the stock market. Various honors, huge amounts of fan mail, and other accolades were bestowed on Wilder.[citation needed]

Autobiography: Pioneer Girl

In 1929–1930, already in her early 60s, Wilder began writing her autobiography, titled Pioneer Girl. At the time, it was rejected by publishers and was never released. At her daughter's urging, Wilder rewrote most of her stories for children. The result was the Little House series of books. In 2014, the South Dakota State Historical Society published an annotated version of Wilder's autobiography, titled Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography.[32][33]

Pioneer Girl includes stories that Wilder felt were inappropriate for children: e.g., a man accidentally immolating himself while drunk, and an incident of extreme violence of a local shopkeeper against his wife, which ended with the man's setting their house on fire. She also describes previously unknown sides of her father's character. According to its publisher, "Wilder's fiction, her autobiography, and her real childhood are all distinct things, but they are closely intertwined." The book's aim was to explore the differences, including incidents with conflicting or non-existing accounts in one or another of the sources.[34]

Later life and death

Upon her daughter's departure from Rocky Ridge Farm, Wilder and her husband moved back into the farmhouse they had built, which had most recently been occupied by friends.[24] From 1935 on, Wilder and her husband were alone at Rocky Ridge Farm. Most of the surrounding area (including the property with the stone cottage Lane had built for them) were sold, but they still kept some farm animals, and tended their flower beds and vegetable gardens. Almost daily, carloads of fans stopped by, eager to meet "Laura" of the Little House books.

The Wilders lived independently and without financial worries until the death of Wilder's husband at the farm, in 1949, aged 92. Wilder remained on the farm. For the next eight years, she lived alone, looked after by a circle of neighbors and friends. She continued an active correspondence with her editors, fans, and friends during these years.

In autumn 1956, the 89-year-old Wilder was severely ill from un-diagnosed diabetes and cardiac issues. She was hospitalized by her daughter, who had arrived for Thanksgiving. Wilder was able to return home on the day after Christmas. However, her health declined after her release from the hospital, and she died in her sleep, at home, on February 10, 1957, three days after her 90th birthday.[35] Wilder was buried beside her husband at Mansfield Cemetery in Mansfield, Missouri. Their daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, was buried next to them upon her death in 1968.[citation needed]

Estate

Following Wilder's death, possession of Rocky Ridge Farmhouse passed to the farmer who had earlier bought the property under a life lease arrangement.[36] The local population put together a non-profit corporation to purchase the house and its grounds, for use as a museum. After some wariness at the notion of seeing the house rather than the books be a shrine to Wilder, Lane came to believe that making a museum of it would draw long-lasting attention to the books. She donated the money needed to purchase the house and make it a museum, agreed to make significant contributions each year for its upkeep, and gave many of her parents' belongings.[37]

In compliance with Wilder's will, her daughter inherited ownership of the Little House literary estate with the stipulation that it be only for her lifetime, with all rights reverting to the Mansfield library after Lane's death. Following Lane's death in 1968, her will beneficiary, Roger MacBride, gained control of the books' copyrights. MacBride was to Lane an informally adopted grandson, as well as her business agent and lawyer. All of his actions carried her apparent approval; at Lane's request, the copyrights to each of Wilder's "Little House" books, as well as those of Lane's own literary works, had been renewed in MacBride's name when the original copyrights expired, during the decade between Wilder's death and Lane's death.

Controversy arose following MacBride's death in 1995, when the Laura Ingalls Wilder Branch of the Wright County Library in Mansfield — the library founded in part by Wilder — decided it was worth trying to recover the rights. The ensuing court case was settled in an undisclosed manner, but MacBride's heirs retained the rights to Wilder's books. From the settlement, the library received enough to start work on a new building.[citation needed]

The popularity of the Little House book series has grown over the years following Wilder's death, spawning a multimillion-dollar franchise of mass merchandising.[citation needed] Results of the franchise have been an additional spinoff book series[citation needed] — some written by MacBride and his daughter, Abigail MacBride Allen — and the long-running television series, starring Melissa Gilbert as Wilder and Michael Landon as her father.

Works

Little House books

The eight "original" Little House books, were published by Harper & Brothers with illustrations by Helen Sewell (the first three) or by Sewell and Mildred Boyle.

- Little House in the Big Woods (1932) — named to the inaugural Lewis Carroll Shelf Award list in 1958

- Farmer Boy (1933) — about Almanzo Wilder growing up in New York

- Little House on the Prairie (1935)

- On the Banks of Plum Creek (1937)[a]

- By the Shores of Silver Lake (1939)[a]

- The Long Winter (1940)[a]

- Little Town on the Prairie (1941)[a]

- These Happy Golden Years (1943)[a]

Other works

- On the Way Home (1962, published posthumously) — diary of the Wilders' move from De Smet, South Dakota to Mansfield, Missouri, edited and supplemented by Rose Wilder Lane[38]

- The First Four Years (1971, published posthumously by Harper & Row), illustrated by Garth Williams

- West from Home (1974, published posthumously), ed. Roger Lea MacBride — Wilder's letters to her husband while visiting their daughter in San Francisco[39]

- Little House in the Ozarks: The Rediscovered Writings (1991)[40] LCCN 91-10820 — collection of pre-1932 articles[41]

- The Road Back Home, part three (the only part previously unpublished) of A Little House Traveler: Writings from Laura Ingalls Wilder's Journeys Across America (2006, Harper) LCCN 2005-14975) — Wilder's record of a 1931 trip with her husband to De Smet, South Dakota, and the Black Hills

- A Little House Sampler (1988 or 1989, U. of Nebraska), with Rose Wilder Lane, ed. William Anderson, OCLC 16578355[42]

- Writings to Young Women — Volume One: On Wisdom and Virtues, Volume Two: On Life As a Pioneer Woman, Volume Three: As Told By Her Family, Friends, and Neighbors[citation needed]

- A Little House Reader: A Collection of Writings (1998, Harper), ed. William Anderson[42]

- Laura Ingalls Wilder & Rose Wilder Lane, 1937–1939 (1992, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library), ed. Timothy Walch — selections from letters exchanged by Wilder and her daughter, with family photographs, OCLC 31440538

- Laura's Album: A Remembrance Scrapbook of Laura Ingalls Wilder (1998, Harper), ed. William Anderson, OCLC 865396917

- Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography (South Dakota Historical Society Press, 2014)[32]

- Before the Prairie Books: The Writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder 1911–1916: The Small Farm[citation needed]

- Before the Prairie Books: The Writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder 1917–1918: the War Years[citation needed]

- Before the Prairie Books: The Writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder 1919–1920: The Farm Home[citation needed]

- Before the Prairie Books: The Writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder 1921–1924, A Farm Woman[citation needed]

- Laura Ingalls Wilder's Most Inspiring Writings[citation needed]

- Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Pioneer Girl's World View: Selected Newspaper Columns (Little House Prairie Series)[citation needed]

- The Selected Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder, edited by William Anderson [43]

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Farm Journalist: Writings from the Ozarks, edited by Stephen W. Hines[44]

Legacy

Documentary

Little House on the Prairie: The Legacy of Laura Ingalls Wilder (February, 2015) is a one-hour documentary film that looks at the life of Wilder. Wilder's story as a writer, wife, and mother is explored through interviews with scholars and historians, archival photography, paintings by frontier artists, and dramatic reenactments.

Historic sites and museums

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Home and Museum, Mansfield, Missouri

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Museum, Pepin, Wisconsin[45]

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Museum, Walnut Grove, Minnesota[46]

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Pageant and Museum, De Smet, South Dakota

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Park and Museum, Burr Oak, Iowa[47]

- Little House on the Prairie Museum, Independence, Kansas[48]

- Wilder Homestead, Malone, NY[49]

Portrayals on screen and stage

Multiple adaptations of Wilder's Little House on the Prairie book series have been produced for screen and stage. In them, the following actresses have portrayed Wilder:

- Melissa Gilbert in the television series Little House on the Prairie and its movie sequels (1974–1984)

- Kazuko Sugiyama (voice) in Laura, The Prairie Girl Japanese anime series (1975–1976)

- Meredith Monroe, Tess Harper (elder version), Alandra Bingham (younger version, part 1), Michelle Bevan (younger version, part 2) in Part 1 and Part 2 of the Beyond the Prairie: The True Story of Laura Ingalls Wilder television films (2000 and 2002)

- Kyle Chavarria in the TV miniseries Little House on the Prairie (2005)

- Kara Lindsay in the Little House on the Prairie book musical (2008–2010)

Wilder Medal

Wilder was five times a runner-up for the annual Newbery Medal, the premier American Library Association (ALA) book award for children's literature.[a] In 1954, the ALA inaugurated a lifetime achievement award for children's writers and illustrators, named for Wilder, and first awarded to her. The Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal recognizes a living author or illustrator whose books, published in the United States, have made "a substantial and lasting contribution to literature for children". As of 2013, it has been conferred 19 times, biennially starting in 2001.[51]

Other

- Google Doodle commemorated her 148th birthday in 2015.[52]

- Hall of Famous Missourians at the Missouri State Capitol — a bronze bust depicting Wilder is on permanent display in the rotunda. She was inducted in 1993.

- Missouri Walk of Fame — Wilder was honored on the Walk in 2006.[citation needed]

- Wilder crater on planet Venus was named after Laura Ingalls Wilder.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Five times from 1938 to 1944 Wilder was one of the runners-up for the American Library Association Newbery Medal, recognizing the previous year's "most distinguished contribution to American literature for children". The honored works were the last five of eight books in the Little House series that were published in her lifetime.[50]

References

- ^ "Laura Ingalls Wilder". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2009-12-19. [full citation needed]

- ^ a b [1] [Wilder index]. Wisconsin Historical Society (wisconsinhistory.org).

Ingalls' home in Pepin became the setting for her first book, Little House in the Big Woods. Archived February 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine - ^ Benge, Janet and Geoff (2005). Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Storybook Life. YWAM Publishing. p. 180. ISBN 1-932096-32-9.

- ^ "What Really Caused Mary Ingalls to Go Blind?". February 4, 2013. American Academy of Pediatrics. Press release announcing Allexan, et al.:

• Allexan, Sarah S.; Byington, Carrie L.; Finkelstein, Jerome I.; Tarini, Beth A. (March 1, 2013). "Blindness in Walnut Grove: How Did Mary Ingalls Lose Her Sight?". Pediatrics. 131:3: 404–06 (doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1438). - ^ Dell'Antonia, KJ (February 4, 2013). "Scarlet Fever Probably Didn't Blind Mary Ingalls". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-02-04.

- ^ Serena, Gordon (February 4, 2013). "Mistaken Infection 'On The Prairie'?". HealthDay; U.S. News & World Report (usnews.com/health-news). Retrieved 2013-02-04.

- ^ "Laura.pdf" (PDF). Little House Wayside; Pepin, Wisconsin (visitpepincounty.com). Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- ^ a b Gormley, Myra Vanderpool; Rhonda R. McClure. "A Genealogical Look at Laura Ingalls Wilder". GenealogyMagazine.com. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ^ "Eunice Sleeman". Edmund Rice (1638) Association (edmund-rice.org). 2002. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

Eunice Sleeman was the mother of Eunice Blood (1782–1862), the wife of Nathan Colby (born 1778), who were the parents of Laura Louise Colby Ingalls (1810–1883), Wilder's paternal grandmother

- ^ Kaye, Frances W. (2000). "Little Squatter on the Osage Diminished Reserve: Reading Laura Ingalls Wilder's Kansas Indians". Great Plains Quarterly. 20 (2): 123–140.

- ^ Anderson, William (1990). Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Iowa Story, pp. 1–2. Burr Oak, IA: L.I.W. Park & Museum.

- ^ "Laura Ingalls Wilder Timeline". Laura Ingalls Wilder. The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum; National Archives and Records Administration (hoover.archives.gov). Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ^ "Laura Ingalls Wilder Timeline". Herbert Hoover Presidential Library & Museum. Herbert Hoover Presidential Library & Museum. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ Anderson, William (1998). Laura's Album. Harper Collins.

- ^ a b Wilder, Laura Ingalls; Wilder, Almanzo (1974). West from Home: Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder, San Francisco, 1915. HarperCollins. p. xvii.

- ^ "Laura Ingalls Wilder Timeline". hoover.archives.gov. West Branch, IA, US: The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "De Smet Info". ingallshomestead.com. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ Miller 1998, p. 80.

- ^ Miller 1998, p. 84.

- ^ "Laura's Life on Rocky Ridge Farm". Laura Ingalls Wilder Historic Home & Museum. November 5, 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- ^ Miller 1998, p. 161.

- ^ Miller 1998, p. 162.

- ^ Miller 2008, p. 24.

- ^ a b Miller 1998, p. 177.

- ^ a b Miller 2008, p. 40.

- ^ Holtz 1993. [full citation needed]

- ^ Miller 1998, pp. 6, 190.

- ^ Miller 2008, pp. 37 et seq.

- ^ a b Thurman, Judith (August 10, 2009). "Wilder Women: The mother and daughter behind the Little House stories". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- ^ Thurman, Judith (August 16, 2012). "A Libertarian House on the Prairie". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- ^ Fraser, Caroline (2012). ""Little House on the Prairie": Tea Party manifesto". Los Angeles Review of Books. October 10, 2012, reprint at Salon (salon.com). Retrieved 2015-02-08.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "Pioneer Girl is out!". November 21, 2014. Pioneer Girl Project (pioneergirlproject.org). South Dakota Historical Society Press. Retrieved 2015-10-15.

- ^ Higgins, Jim (December 5, 2014). "Laura Ingalls Wilder's annotated autobiography, 'Pioneer Girl,' shows writer's world, growth". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 2014-12-23.

- ^ Flood, Alison (August 25, 2014). "Laura Ingalls Wilder memoir reveals truth behind Little House on the Prairie". The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

- ^ "Laura I. Wilder, Author, Dies at 90. Writer of the 'Little House' Series for Children Was an Ex-Newspaper Editor. Wrote First Book at 65". The New York Times. Associated Press. February 12, 1957. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

Mrs. Laura Ingalls Wilder, author of the 'Little House' series of children's books, died yesterday at her farm near here after a long illness. Her age was 90.

Article preview. Article available only by subscription or purchase. (subscription required) - ^ Holtz 1995, pp. 334, 338.

- ^ Holtz 1995, p. 340.

- ^ "On the Way Home: The Diary Of A Trip From South Dakota To Mansfield, Missouri, In 1894". Kirkus Reviews. November 1, 1962. Retrieved 2015-10-02.

- ^ "West From Home: Letters Of Laura Ingalls Wilder, San Francisco, 1915". Kirkus Reviews. March 1, 1974. Retrieved 2015-10-02.

- ^ Wilder, Laura (1991). Hines, Stephen W. (ed.). Little House in the Ozarks: The Rediscovered Writings. Nashville: T. Nelson. ISBN 0883659689.

- ^ "Little House in the Ozarks". Kirkus Reviews. July 15, 1991. Retrieved 2015-10-02. "Wilder was an experienced journalist; many of her articles, often written for a publication called Farmer's Week, described her life on the Missouri farm where she and Almanzo had finally settled".

- ^ a b "A Little House Reader: A Collection of Writings by Laura Ingalls Wilder". Kirkus Reviews. December 15, 1997. Retrieved 2015-10-02.

- ^ "The Selected Letters Of Laura Ingalls Wilder". ingallshomestead.com. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ "Laura Ingalls Wilder Farm Journalist". ingallshomestead.com. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ "Home". Laura Ingalls Wilder Museum (lauraingallspepin.com). Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- ^ "Laura Ingalls Wilder Museum". Walnut Grove, MN (walnutgrove.org). Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- ^ "Home". Laura Ingalls Wilder Park and Museum (lauraingallswilder.us). Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ "Home". Little House on the Prairie Museum (littlehouseontheprairiemuseum.com). Retrieved 2015-02-08.

- ^ "Wilder Homestead, Boyhood Home of Almanzo". almanzowilderfarm.com. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^

"Newbery Medal and Honor Books, 1922–Present". ALSC. ALA.

"The John Newbery Medal". ALSC. ALA. Retrieved 2013-03-08. - ^

"Laura Ingalls Wilder Award, Past winners". Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). American Library Association (ALA).

"About the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award". ALSC. ALA. Retrieved 2013-03-08. - ^ "Laura Ingalls Wilder's 148th Birthday". Doodles; Google (google.com/doodles). Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- Citations

- Holtz, William (1993). The Ghost in the Little House: A Life of Rose Wilder Lane. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-0887-8.

- Holtz, William (1995). The Ghost in the Little House: A Life of Rose Wilder Lane. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1015-5. – Edition: illustrated, reprint, revised; 427 pp.; selections and bibliographic data retrieved from Google Books 2015-10-15.

- Miller, John E. (1998). Becoming Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Woman Behind the Legend. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1167-4.

- Miller, John E. (2008). Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane: Authorship, Place, Time, and Culture. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1823-7.

Further reading

- Sickels, Amy (2007). Laura Ingalls Wilder. Facts On File, Incorporated. p. 109. ISBN 9781438123783. Retrieved 2014-10-25. – at Google Books

External links

- Laura Ingalls Wilder in MNopedia, the Minnesota Encyclopedia

- Beyond Little House - Laura Ingalls Wilder Legacy and Research Association

- Laura Ingalls Wilder, Frontier Girl

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Gallery, OldPhotoArchive

- Laura Ingalls Wilder at Library of Congress, with 144 library catalog records

- Laura Ingalls Wilder at Find a Grave

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Memorial Society, De Smet, South Dakota

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Historic Home & Museum, Mansfield, Missouri

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Museum, Walnut Grove, Minnesota:

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Park & Museum, Burr Oak, Iowa

- 1867 births

- 1957 deaths

- 20th-century American novelists

- 20th-century American writers

- 20th-century women writers

- American children's writers

- American Congregationalists

- American libertarians

- American pioneers

- American people of English descent

- American schoolteachers

- American women novelists

- Deaths from diabetes

- Delano family

- Ingalls family

- Laura Ingalls Wilder

- Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal winners

- Newbery Honor winners

- People from Kingsbury County, South Dakota

- People from Pepin County, Wisconsin

- People from Wright County, Missouri

- Wilder family

- Women children's writers

- Writers from Missouri

- Writers from South Dakota

- Writers from Wisconsin