Inanna

| Inanna | |

|---|---|

Queen of Heaven Goddess of love, beauty, sex, desire, fertility, war, combat, and political power | |

| |

| Abode | Heaven |

| Planet | Venus |

| Symbol | Sky, Clouds, Wars, Birth, Skin |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | usually Nanna and Ningal (though her father is sometimes alternatively given as Enki or An along with an unknown mother) |

| Siblings | Utu, Ishkur and Ereshkigal |

| Consort | Dumuzi or Tammuz |

| Children | Lulal and Shara |

| Equivalents | |

| Canaanite | Astarte |

| Greek | Aphrodite |

| Babylonian | Ishtar |

Inanna (/ɪˈnɑːnə/; Template:Lang-sux Dinanna)[2] was the Sumerian goddess of love, beauty, sex, desire, fertility, war, combat, and political power, equivalent to the Akkadian and Babylonian goddess Ishtar. She was also the patron goddess of the Eanna temple at the city of Uruk, which was her main cult center. She was associated with the planet Venus and her most prominent symbols included the lion and the eight-pointed star.

Inanna was one of the most widely adored and venerated deities in the ancient Sumerian pantheon, appearing in nearly every story that they told. Many of her myths involved her taking over the domains of other deities. She was believed to have stolen the mes, which represented all positive and negative aspects of civilization, from Enki, the god of wisdom. She was also believed to have taken over the Eanna temple from An, the god of the sky, thereby becoming the Queen of Heaven. Inanna, however, was not always portrayed positively; she also had a fierce temper. She was believed to have destroyed the kur of Ebih out of jealous pride and to have unleashed mass chaos upon the world after being raped in her sleep by the gardener Shukaletuda.

Her most famous myth, however, is the story of her descent into and return from Kur, the ancient Sumerian underworld, a myth in which she attempts to conquer the domain of her sister Ereshkigal, the queen of the Underworld, but is instead deemed guilty of hubris by the seven judges of the Underworld and struck dead, before being brought back to life three days later through the intervention of the god Enki due to the fervent pleading of her sukkal, or personal attendant, Ninshubur, even after all the other gods reject her. Her husband Dumuzid is dragged down to the Underworld by the galla, the guardians of the Underworld, as her replacement, but is eventually permitted to return to heaven for half the year while his sister Geshtinanna remains in the Underworld for the other half, resulting in the cycle of the seasons.

Origins

Inanna was the most prominent female deity in ancient Mesopotamia.[3] As early as the Uruk period (ca. 4000–3100 BC), Inanna was associated with the city of Uruk. The famous Uruk Vase (found in a deposit of cult objects of the Uruk III period) depicts a row of naked men carrying various objects, including bowls, vessels, and baskets of farm products, and bringing sheep and goats, to a female figure facing the ruler. This figure is ornately dressed for a divine marriage, and attended by a servant. The female figure holds the symbol of the two twisted reeds of the doorpost, signifying Inanna behind her, while the male figure holds a box and stack of bowls, the later cuneiform sign signifying En, or high priest of the temple. The symbol of a ring-headed doorpost was closely associated with Inanna, especially during the Uruk period.[3]

Seal impressions from the Jemdet Nasr period (ca. 3100–2900 BC) show a fixed sequence of symbols representing various cities, including those of Ur, Larsa, Zabalam, Urum, Arina, and probably Kesh. This list probably reflects the report of contributions to Inanna at Uruk from cities supporting her cult. A large number of similar seals have been discovered from the slightly later Early Dynastic I phase at Ur, in a slightly different order, combined with the rosette symbol of Inanna, that were definitely used for this purpose. These seals were used to lock storerooms to preserve materials set aside for her cult.[4]

The myth of Inanna's assumption of the me from Enki, has been interpreted as a late addition to Sumerian mythology, possibly associated with the archaeologically confirmed eclipse in the importance of Eridu and the rise of the importance of Uruk at the end of the Ubaid period. Inanna's primary center of worship was the Eanna temple in Uruk, which seems to have originally been dedicated to Anu, the head of the Sumerian pantheon prior to the rise of Enlil of Nippur.[5]

Etymology

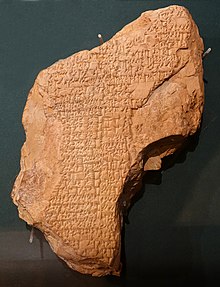

Inanna's name derives from the Sumerian phrase nin-an-ak, meaning "Lady of Heaven." The cuneiform sign for Inanna (𒈹), however, is not a ligature of the signs lady (Sumerian: nin; Cuneiform: 𒊩𒌆 SAL.TUG2) and sky (Sumerian: an; Cuneiform: 𒀭 AN).[6] These difficulties led some early Assyriologists to suggest that Inanna may have originally been a Proto-Euphratean goddess, possibly related to the Hurrian mother goddess Hannahannah, who was only later accepted into the Sumerian pantheon, an idea supported by Inanna's youthfulness, and as well as the fact that, unlike the other Sumerian divinities, she seems to have initially lacked a distinct sphere of responsibilities.[7] The view that there was a Proto-Euphratean substrate language in Southern Iraq before Sumerian is not widely accepted by modern Assyriologists.[8]

Worship

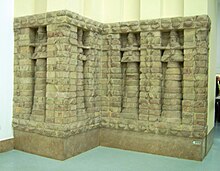

Inanna was one of the most widely venerated deities in the Sumerian pantheon.[9][6] Many shrines and temples dedicated to Inanna were built along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Her main cult center was the Eanna temple, whose name means "House of Heaven" (Sumerian: e2-anna; Cuneiform: 𒂍𒀭 E2.AN),[10] in Uruk.[11] The original patron deity of this fourth-millennium city was probably An. After its dedication to Inanna, the temple seems to have housed priestesses of the goddess. According to Gwendolyn Leick, an anthropologist known for her writings about Mesopotamia, persons of asexual or hermaphroditic bodies and feminine men were particularly involved in the worship and ritual practices of Inanna's temples (see gala).[12]

In his book The Sacred Marriage Rite, the widely respected scholar Samuel Noah Kramer proposes that, in late Sumerian history, towards the end of the third millennium B.C., kings of Uruk may have established their legitimacy by taking on the role of the shepherd Dumuzid, Inanna's consort in the temple for one night on the tenth day of the Akitu, the Sumerian new year festival, which was celebrated annually at the spring equinox. The king would then partake in a "sacred marriage" ceremony in which he would engage in ritualized sexual intercourse with the high priestess of Inanna, who took on the role of the goddess herself.[13]

Iconography

Inanna's cuneiform ideogram was a hook-shaped twisted knot of reeds, representing the doorpost of the storehouse, a common symbol of fertility and plenty.[14] The eight-pointed star or rosette was also an important symbol of hers.[15] Inanna was associated with lions - even then a symbol of power. During the Akkadian Period, Ishtar was frequently depicted standing on the backs of two lionesses,[16] but, even during Sumerian times, Inanna was already associated with lions; a chlorite bowl from the temple of Inanna at Nippur depicts a large feline battling a giant snake and a cuneiform inscription on the bowl reads "Inanna and the Serpent," indicating that the cat is supposed to represent the goddess.[17]

Inanna as the planet Venus

Much like the Greco-Roman goddesses Aphrodite[18] and Venus,[19] Inanna was associated with the planet Venus,[14] which at that time was regarded as two stars, the "morning star" and the "evening star."[20] Several hymns praise Inanna in her role as the goddess of the planet Venus. Theology professor Jeffrey Cooley has argued that, in many myths, Inanna's movements may correspond with the movements of the planet Venus in the sky. In Inanna's Descent to the Underworld, unlike any other deity, Inanna is able to descend into the netherworld and return to the heavens. The planet Venus appears to make a similar descent, setting in the West and then rising again in the East. An introductory hymn describes Inanna leaving the heavens and heading for Kur, what could be presumed to be, the mountains, replicating the rising and setting of Inanna to the West. In Inanna and Shukaletuda, Shukaletuda is described as scanning the heavens in search of Inanna, possibly searching the eastern and western horizons. In the same myth, while searching for her attacker, Inanna herself makes several movements that seemingly correspond with the movements of Venus in the sky.[21]

Because the movements of Venus appear to be discontinuous (it disappears due to its proximity to the sun, for many days at a time, and then reappears on the other horizon), some cultures did not recognize Venus as single entity, but rather regarded the planet as two separate stars on each horizon as the morning and evening star. The Mesopotamians, however, most likely understood that the planet was one entity. A cylinder seal from the Jemdet Nasr period expresses the knowledge that both morning and evening stars were the same celestial entity.[21] The discontinuous movements of Venus relate to both mythology as well as Inanna's dual nature.[21] As both the goddess of love and war, with both masculine and feminine qualities, Inanna is poised to respond, occasionally with outbursts of temper.

Inanna was associated with the eastern fish of the last of the zodiacal constellations, Pisces. Her consort Dumuzi was associated with the contiguous first constellation, Aries.[22]

Character

Inanna's character was oftentimes portrayed in an extremely contradictory manner. The Sumerians worshipped her as the goddess of love, but she was not seen as a role model for how lovers ought to behave.[23] A description of her from one of her hymns declares, "When the servants let the flocks loose, and when cattle and sheep are returned to cow-pen and sheepfold, then, my lady, like the nameless poor, you wear only a single garment. The pearls of a prostitute are placed around your neck, and you are likely to snatch a man from the tavern."[24] In the later Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh points out the goddess Ishtar's infamous ill-treatment of her lovers. Inanna, the Sumerian precursor to the Akkadian Ishtar, also has a very complicated relationship with her lover Dumuzid in Inanna's Descent to the Underworld.[23]

Somewhat paradoxically, Inanna was also worshipped as one of the Sumerian war deities. One of her hymns declares: "She stirs confusion and chaos against those who are disobedient to her, speeding carnage and inciting the devastating flood, clothed in terrifying radiance. It is her game to speed conflict and battle, untiring, strapping on her sandals."[25]

Mythology

Enki and the World Order

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

The poem of "Enki and the World Order" begins by describing the god Enki and his establishment of the cosmic organization of the universe.[26] Towards the end of the poem, however, the story takes a sudden twist; Inanna comes to Enki and complains that he has assigned a domain and special powers to all of the other gods except for her.[27] She declares that she has been treated unfairly.[28] Enki responds by telling her that she already has a domain and that he does not need to assign her one.[29]

The huluppu tree

This myth, found in the preamble to the epic of Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld,[30] centers around a young Inanna, not yet stable in her power.[31] It begins with a huluppu tree, which Kramer identifies as possibly a willow,[32] growing on the banks of the river Euphrates. Inanna moves the tree to her garden in Uruk with the intention to carve it into a throne once it is fully grown. The tree grows and matures, but the serpent "who knows no charm," the Anzû-bird, and Lilitu, the Sumerian forerunner to the Biblical Lilith, all take up residence within the tree, causing Inanna to cry with sorrow.[32] The hero Gilgamesh, who, in this story, is portrayed as her brother, comes along and slays the serpent, causing the Anzû-bird and Lilitu to flee.[33] Gilgamesh's companions chop down the tree and carve its wood into a bed and a throne, which they give to Inanna,[34] who fashions a pikku and a mikku (probably a drum and drumsticks respectively, although the exact identifications are uncertain),[35] which she gives to Gilgamesh as a reward for his heroism.[36]

Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta

Inanna has a central role in the myth of Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta,[37] which centers around the rivalry between the rulers of Aratta and Uruk for the heart of Inanna. Ultimately, this rivalry results in natural resources coming to Uruk and the invention of writing. The text describes a tension between the cities:

The lord of Aratta placed on his head the golden crown for Inana. But he did not please her like the lord of Kulaba. Aratta did not build for holy Inana — unlike the Shrine E-ana.[38]

The city Aratta is structured as a mirror image of Uruk, only Aratta has natural resources that Uruk needs, such as gold, silver, and lapis lazuli. Enmerkar, king in Uruk, comes to Inanna requesting that a temple be built in Uruk with stones from Aratta, and she orders him to find a messenger to cross the Zubi mountains and go to the Lord of Aratta demanding precious metals for the temple.[39] The messenger makes the journey and all the peoples he passes along the way praise Inanna. He makes his demands, and the Lord of Aratta refuses, saying that Aratta will not submit to Uruk. He is upset, however, to learn that Inanna is pleased with the Eanna shrine.[40] The Lord of Aratta issues a challenge to Enmerkar to bring barley to Aratta because Aratta is currently experiencing a severe famine. Enmerkar mobilizes men and donkeys to deliver the food. Still, the Lord of Aratta will not submit.[41] He orders Enmerkar to complete a series of riddles or challenges. Enmerkar, with the wisdom of Enki, succeeds at every task. Eventually, the Lord of Aratta challenges Enmerkar to have a champion from each city fight in single combat.[42] By this point, however, the messenger is tired. Enmerkar gives him a message, but he is unable to repeat it verbally so, instead, he inscribes the message on a tablet, thus inventing writing.[43]

The Lord of Aratta cannot read the text, but the god Ishkur causes it to rain, ending the drought in Aratta. The Lord of Aratta decides that his city has not been forsaken after all and the champion of Aratta dresses in a "garment of lion skins,"[44] possibly in honor of Inanna.[45] The end of the text is unclear, but it seems that the city of Uruk is able to access Aratta's resources.

Theft of the mes

One of the most important myths involving Inanna is a myth that comes from an ancient Sumerian epic poem entitled "Inanna and Enki," which tells the story of how Inanna stole the sacred mes from Enki, the ancient Sumerian god of culture. In ancient Sumerian mythology, the mes were sacred documents or tablets that contained all of the blueprints for human civilization. Each me embodied one specific aspect of human culture. These aspects were very diverse and the mes listed in the poem include abstract concepts such as Truth, Victory, and Counsel, technologies such as writing and weaving, and also social constructs such as law, priestly offices, kingship, and prostitution. The mes were believed to grant power over, or possibly existence to, all the aspects of civilization, both positive and negative.[46]

In the myth, Inanna travels from her own city of Uruk to Enki's city of Eridu, where she visits his temple, the E-Abzu. Inanna is greeted by Enki's sukkal, Isimud, who offers her food and drink. Inanna starts up a drinking competition with Enki. Then, once she has gotten Enki thoroughly intoxicated, Inanna cunningly persuades Enki into giving her the mes using clever rhetoric. Inanna flees from Eridu in the Boat of Heaven, taking the mes back with her to Uruk. Enki wakes up to discover that the mes are gone and asks Isimud what has happened to them. Isimud replies that Enki has given all of them to Inanna. Enki becomes infuriated and sends multiple sets of fierce monsters after Inanna to take back the mes before she reaches the city of Uruk. Inanna's sukkal, Ninshubur, however, fends off all of the monsters that Enki sends after them. Through Ninshubur's aid, Inanna successfully manages to take the mes back with her to the city of Uruk. After Inanna escapes, Enki reconciles with her and bids her a positive farewell.[47]

It is possible that this legend may represent a historic transfer of power from the city of Eridu to the city of Uruk. It is also possible that this legend may be a symbolic representation of Inanna's maturity and her readiness to become the Queen of Heaven.[48]

Destruction of Ebih

This myth comes from a 184-line-long poem entitled "Inanna and Ebih," which describes Inanna's confrontation with the Kur of Ebih.[49] In the poem, the exact meaning of the word Kur is somewhat unclear since the word had many different possible meanings. The word usually referred to the Zagros mountain range (Jebel Hamrin, which is located in modern-day Iraq).[50] The same word, however, was commonly used in Sumerian mythology to refer to the first dragon.[51]

The poem begins with an introductory hymn praising Inanna.[52] The goddess then journeys all over the entire world, until she comes across Mount Ebih, and becomes infuriated by its glorious might and natural beauty, considering its very existence as an outright affront to her own authority. She rails at Mount Ebih, shouting:

Mountain, because of your elevation, because of your height,

Because of your goodness, because of your beauty,

Because you wore a holy garment,

Because An organized(?) you,

Because you did not bring (your) nose close to the ground,

Because you did not press (your) lips in the dust.[53]

Inanna petitions to An, the Sumerian god of the heavens, to allow her to destroy Mount Ebih. An responds by giving Inanna a lengthy and detailed account of all the terrible mischief that the mountain has inflicted against the gods. Ultimately, however, An warns Inanna against attacking the mountain, but Inanna ignores his warnings. She then proceeds to attack and destroy Mount Ebih regardless, utterly annihilating it and leaving massive destruction in her wake. In the conclusion of the myth, she explains to Mount Ebih why she attacked it.[49] In Sumerian poetry, the phrase "destroyer of Kur" is occasionally used as one of Inanna's epithets.[54]

Samuel Noah Kramer interprets the poem as an account of Inanna slaying a dragon. He identifies two earlier myths also describing the slaying of a dragon. In the two earlier versions of the myth of the destruction of the Kur, the hero responsible for the slaying of the Kur is either Enki or Ninurta.[51] The possibility that, in this myth, Inanna plays the role of the dragon-slayer is highly unusual since the hero of a dragon-slaying myth is almost always male.

Inanna and Shukaletuda

"Inanna and Shukaletuda" begins with a hymn to Inanna, praising her as the planet Venus. It then introduces Shukaletuda, a gardener who is terrible at his job and partially blind. All of his plants die, except for one poplar tree. Shukaletuda prays to the gods for guidance in his work. To his surprise, the goddess Inanna sees his one poplar tree and decides to rest under the shade of its branches. Shukaletuda removes his clothes and rapes Inanna while she sleeps. When the goddess wakes up and realizes she has been violated, she becomes furious and determines to bring her attacker to justice. In a fit of rage, Inanna unleashes horrible plagues upon the Earth, turning water into blood, to punish and identify her rapist. Shukaletuda, terrified for his life, pleads his father for advice on how to escape Inanna's wrath. His father tells him to hide in the city, amongst the hordes of people, where he will hopefully blend in. Inanna searches the mountains of the East for her attacker, but is not able to find him. She then releases a series of storms and closes all roads to the city, but is still unable to find Shukaletuda in the mountains, so she asks Enki to help her find him, threatening to leave her temple in Uruk if he does not. Enki consents and allows Inanna to "fly across the sky like a rainbow." Inanna finally locates Shukaletuda, who vainly attempts to invent excuses for his crime against her. Inanna rejects these excuses and kills him.[21]

Theology professor Jeffrey Cooley has cited the story of Shukaletuda as a Sumerian astral myth, claiming that the movements of Inanna in the story correspond with the movements of the planet Venus. He has even suggested that, while Shukaletuda was praying to the goddess, he may have been looking toward Venus on the horizon.[21]

Humbling of Gudam

This fragmentary myth focuses on the actions of Gudam, who is described as a fierce warrior, who dines on flesh and drinks blood instead of beer. Gudam walks through Uruk, killing many and damaging the Eanna temple, until a "fisherman of Inanna" turns his axe against him and defeats him. Gudam, humbled, pleads to Inanna for forgiveness, promising to praise her through words and offerings.[55]

Takeover of the Eanna Temple

This myth, also fragmentary, begins with a conversation between Inanna and her brother Utu in which Inanna laments that the Eanna temple is not within their domain and resolves to claim it as her own. The text becomes increasingly fragmentary at this point in the narrative, but appears to describe her difficult passage through a marshland to reach the temple while a fisherman instructs her on which route is the best to take.

Ultimately, Inanna reaches her father An, who is shocked by her arrogance in attempting to capture the Eanna temple for herself, but nevertheless concedes that she has succeeded and that it is now her domain. The text ends with a hymn expounding Inanna's greatness.[56] This myth may represent an eclipse in the authority of the priests of An in Uruk and a transfer of power to the priests of Inanna.[57]

Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzid

This myth begins with a rather playful conversation between Inanna and Utu, who incrementally reveals to her that it is time for her to marry.[58] She is courted by a farmer named Enkimdu and a shepherd named Dumuzid. At first, Inanna prefers the farmer, but Utu and Dumuzid gradually persuade her that Dumuzid is the better choice for a husband, arguing that, for every gift the farmer can give to her, the shepherd can give her something even better. In the end, Inanna marries Dumuzid. The shepherd and the farmer reconcile their differences, offering each other gifts.[59] Samuel Noah Kramer compares the myth to the Biblical story of Cain and Abel because both myths center around a farmer and a shepherd competing for divine favor and, in both stories, the deity in question ultimately chooses the shepherd.[60]

Descent into the Underworld

The story of Inanna's descent to the underworld is a relatively well-attested and reconstructed composition.

In Sumerian religion, the Kur was conceived of as a dreary, dark place; a home to deceased heroes and ordinary people alike, ruled by Inanna's sister, the goddess Ereshkigal. While everyone suffered an eternity of poor conditions, certain behavior while alive, notably creating a family to provide offerings to the deceased, could alleviate conditions somewhat.

Inanna's reason for visiting the underworld is unclear. She tells the gatekeeper of the underworld that she wishes to attend the funeral rites of Ereshkigal's husband Gugalanna, but, in The Epic of Gilgamesh, Gugalanna is the Bull of Heaven, who is killed by Gilgamesh and Enkidu. To add further confusion, Ereshkigal's husband is typically the plague god Nergal.[61]

Before leaving, Inanna instructs her minister and servant Ninshubur to plead with the deities Enlil, Nanna, Anu, and Enki to rescue her if she does not return after three days. The laws of the underworld dictate that, with the exception of appointed messengers, those who enter it may never leave.

Inanna dresses elaborately for the visit, with a turban, a wig, a lapis lazuli necklace, beads upon her breast, the 'pala dress' (the ladyship garment), mascara, pectoral, a golden ring on her hand, and she held a lapis lazuli measuring rod. These garments are each representations of powerful mes she possesses. Perhaps Inanna's garments, unsuitable for a funeral, along with Inanna's haughty behavior, make Ereshkigal suspicious.[62]

Following Ereshkigal's instructions, Neti, the gatekeeper of the underworld, tells Inanna she may enter the first gate of the underworld, but she must hand over her lapis lazuli measuring rod. She asks why, and is told, "It is just the ways of the Underworld." She obliges and passes through. Inanna passes through a total of seven gates, at each one removing a piece of clothing or jewelry she had been wearing at the start of her journey, thus stripping her of her power. When she arrives in front of her sister, she is naked:

"After she had crouched down and had her clothes removed, they were carried away. Then she made her sister Erec-ki-gala rise from her throne, and instead she sat on her throne. The Anna, the seven judges, rendered their decision against her. They looked at her – it was the look of death. They spoke to her – it was the speech of anger. They shouted at her – it was the shout of heavy guilt. The afflicted woman was turned into a corpse. And the corpse was hung on a hook."

Three days and three nights pass, and Ninshubur, following instructions, goes to the temples of Enlil, Nanna, Anu, and Enki, and pleads with each of them to rescue Inanna. The first three deities refuse, saying Inanna's fate is her own fault, but Enki is deeply troubled and agrees to help. He creates two asexual figures named gala-tura and the kur-jara from the dirt under the fingernails of the deities. He instructs them to appease Ereshkigal and, when she asks them what they want, ask for the corpse of Inanna, which they must sprinkle with the food and water of life. When they come before Ereshkigal, she is in agony like a woman giving birth. She offers them whatever they want, including life-giving rivers of water and fields of grain, if they can relieve her; nonetheless they take only the corpse.

The gala-tura and the kur-jara sprinkle Inanna's corpse with the food and water of life and revive her. Galla demons sent by Ereshkigal follow Inanna out of the Underworld, insisting that she is not free to go until someone else takes her place. They first come upon Ninshubur and attempt to take her, but Inanna stops them, insisting that Ninshubur is her loyal servant, who had rightly mourned her while she was in the underworld. They next come upon Cara, Inanna's beautician, still in mourning. The demons attempt to take him, but Inanna insists that they may not, as he too had mourned her. They next come upon Lulal, also in mourning. The demons try to take him, but Inanna stops them once again.

Finally, they come upon Dumuzid, Inanna's husband. Despite Inanna's fate, and in contrast to the other individuals who were properly mourning Inanna, Dumuzid is lavishly clothed and resting beneath a tree, or upon her throne, entertained by slave-girls. Inanna, displeased, decrees that the demons shall take him, using language which echoes the speech Ereshkigal gave while condemning her. The demons then drag Dumuzid down to the Underworld.

In other recensions of the story, Dumuzid tries to escape his fate, and is able to flee from the demons for a time, as Inanna's brother Utu, the god of the Sun, repeatedly intervenes and transforms Dumuzid into a variety of different animals, enabling him to escape. Nonetheless, the galla eventually capture Dumuzid and drag him down to the Underworld. However, Geshtinanna, Dumuzid's sister, out of love for him, begs to be taken in his place. Inanna decrees that Dumuzid will spend half the year in the underworld with Ereshkigal, but that his sister will take the other half.[63] Inanna, displaying her typically capricious behavior, mourns Dumuzid's time in the underworld. This she reveals in a haunting lament of his deathlike absence from her, for "[he] cannot answer . . . [he] cannot come/ to her calling . . . the young man has gone."[64] Her own powers, notably those connected with fertility, subsequently wane, to return in full when he returns from the netherworld each six months. This cycle then approximates the shift of seasons.

Interpretations of the Descent into the Underworld

Folklorist Diane Wolkstein interprets the myth as a union between Inanna and her own "dark side": her twin sister-self, Ereshkigal. When Inanna ascends from the Underworld, it is through Ereshkigal's powers, but, while Inanna is in the underworld, it is Ereshkigal who apparently takes on the powers of fertility. The poem ends with a line in praise, not of Inanna, but of Ereshkigal. Wolkstein interprets the narrative as a praise-poem dedicated to the more negative aspects of Inanna's domain, symbolic of an acceptance of the necessity of death in order to facilitate the continuance of life.[65] Joseph Campbell interprets the myth as being about the psychological power of a descent into the unconscious, the realization of one's own strength through an episode of seeming powerlessness, and the acceptance of one's own negative qualities.[66]

Conversely, Joshua Mark argues that the most likely moral intended by the original author of the Descent of Inanna is that there are always consequences for one's actions: "The Descent of Inanna, then, about one of the gods behaving badly and other gods and mortals having to suffer for that behavior, would have given to an ancient listener the same basic understanding anyone today would take from an account of a tragic accident caused by someone’s negligence or poor judgment: that, sometimes, life is just not fair."[67]

Another recent interpretation, by Clyde Hostetter, holds that the myth is an allegorical report of related movements of the planets Venus, Mercury, and Jupiter; and those of the waxing crescent Moon in the Second Millennium, beginning with the spring equinox and concluding with a meteor shower near the end of one synodic period of Venus. The three-day disappearance of Inanna refers to the three-day planetary disappearance of Venus between its appearance as a morning or evening star. The fact that Gugalana is slain refers to the disappearance of the constellation Taurus when the sun rises in that part of the sky, which in the Bronze Age marked the occurrence of the vernal equinox.[68]

Family

In different traditions, Inanna is described as either the daughter of the sky god An or as the daughter of the moon god Nanna.[69] In different versions of her stories, her siblings sometimes include the sun god Utu,[70] the rain god Ishkur, and the Queen of the Underworld Ereshkigal. In nearly all of her myths, her sukkal is the goddess Ninshubur. Dumuzid, the god of shepherds, is usually described as Inanna's husband,[70] although Inanna's loyalty to him is questionable; in the myth of her descent into the Underworld, she abandons Dumuzi and permits the galla demons to drag him down into the Underworld as her replacement,[71] but in the later myth of "The Return of Dumuzi," Inanna paradoxically mourns over Dumuzi's death and ultimately decrees that he will be allowed to return to Heaven to be with her for one half of the year.[72]

Influence on other pantheons

The cult of Inanna influenced the cult of the Akkadian and Babylonian goddess Ishtar to such a profound extent that the two goddesses were widely considered to be the same.[73] The cult of Ishtar, in turn, gave rise to the cult of the Phoenician goddess Astarte, which either gave rise to or at least heavily influenced the later cult of the Greek goddess Aphrodite.[74] The cult of Inanna may also have influenced the deities Ainina and Danina of the Caucasian Iberians mentioned by the medieval Georgian Chronicles.[75]

Role in modern feminism

Inanna has become an important figure in modern feminist theory largely due to the fact that she is one of the few major female deities in the otherwise male-dominated Sumerian pantheon. Gavin White has even gone so far as to claim that Inanna was once regarded in parts of Sumer as the mother of all humanity.[76]

In January 2012 the Israeli feminist artist, Liliana Kleiner, presented in Jerusalem an exhibition of paintings of Inanna inspired by the myths described above.[77] Inanna is one of the names on the Heritage Floor of The Dinner Party by American feminist artist Judy Chicago as a related woman to Ishtar, who has a seat at the table.[78]

Author and historian Anne O Nomis has cited the Sumerian myth of "Inanna and Ebih" as an early example of the archetype of a powerful female displaying dominating behaviors and forcing gods and men into submission to her.[79] She describes Inanna's rituals as "imbued with pain and ecstasy, bringing about initiation and journeys of altered consciousness; punishment, ecstasy, lament and song, participants exhausting themselves with weeping and grief."[80]

Dates (approximate)

| Historical sources | ||

| Time | Period | Source |

| c. 5300–4100 BC | Ubaid period | |

| c. 4100–2900 BC | Uruk period | Uruk vase |

| c. 2900–2334 BC | Early Dynastic period | |

| c. 2334–2218 BC | Akkadian Empire | writings by Enheduanna: Nin-me-šara, "The Exaltation of Inanna" |

| c. 2218–2047 BC | Gutian Period | |

| c. 2047–1940 BC | Ur III Period | Inanna and Enki |

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Collins 1994, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses – Inana/Ištar (goddess)

- ^ a b Black & Green 1992.

- ^ Van der Mierop 2007.

- ^ Harris, Rivkah (February 1991). "Inanna-Ishtar as Paradox and a Coincidence of Opposites". History of Religions. 30 (3): 261–278. doi:10.1086/463228. JSTOR 1062957.

- ^ a b Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. xiii-xix.

- ^ Harris, Rivkah (February 1991). "Inanna-Ishtar as Paradox and a Coincidence of Opposites". History of Religions. 30 (3): 261–278. doi:10.1086/463228. JSTOR 1062957.

- ^ Rubio, Gonzalo (1999). "On the Alleged "Pre-Sumerian Substratum"". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 51: 1–16. JSTOR 1359726.

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 101 "the seemingly ubiquitous Inanna". sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFKramer1961 (help)

- ^ é-an-na = sanctuary ('house' + 'Heaven'[='An'] + genitive) (Halloran 2009)

- ^ modern-day Warka, Biblical Erech

- ^ Leick 1994.

- ^ Kramer 1970.

- ^ a b Thorkild 1976

- ^ Black & Green 1992, pp. 156, 169–170

- ^ Black & Green 1992, pp. 156, 169–170

- ^ Collins 1994, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Greene, Ellen (1999). Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches. University of California Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-520-20601-0.

- ^ Guillemin, Amédée; Lockyer, Norman; Proctor, Richard Anthony (1878). The Heavens: An Illustrated Handbook of Popular Astronomy. London: Richard Bentley & Son. p. 67. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, pp. 108–9

- ^ a b c d e Cooley, Jeffrey L. (2008). "Inana and Šukaletuda: a Sumerian Astral Myth". KASKAL. 5: 161–172. ISSN 1971-8608.

- ^ Foxvog, D. (1993). "Astral Dumuzi". In Hallo, William W.; Cohen, Mark E.; Snell, Daniel C.; et al. (eds.). The Tablet and the scroll: Near Eastern studies in honor of William W. Hallo (2nd ed.). CDL Press. p. 106. ISBN 0962001392.

- ^ a b Black & Green 1992, pp. 108–9.

- ^ Voices From the Clay: The Development of Assyro-Babylonian Literature. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1965.

- ^ Enheduanna pre 2250 BCE "A hymn to Inana (Inana C)". The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. 2003. lines 18–28. 4.07.3.

- ^ Kramer 1963, pp. 172–174.

- ^ Kramer 1963, p. 174.

- ^ Kramer 1963, p. 182.

- ^ Kramer 1963, p. 183.

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 30. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFKramer1961 (help)

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 141.

- ^ a b Kramer 1961, p. 33. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFKramer1961 (help)

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 33–34. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFKramer1961 (help)

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 140.

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 34. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFKramer1961 (help)

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 9.

- ^ "Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta". The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. 2006. 1.8.2.3.

- ^ Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta, lines 25–32

- ^ Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta, lines 33–104; 108–133

- ^ Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta, lines 160–241

- ^ Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta, lines 242–372

- ^ Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta, lines 373–461

- ^ Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta, lines 500–514

- ^ Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta, lines 536–577

- ^ Especially her Akkadian counterpart Ishtar was represented with the lion as her beast. C.f. Black & Green 1992, p. 109

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 66. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFKramer1961 (help)

- ^ http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr131.htm

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 146-150.

- ^ a b http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr132.htm

- ^ Postgate, Nicholas (2004). Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. Taylor & Francis. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-415-24587-6.

- ^ a b Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961). Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.: Revised Edition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 76–83. ISBN 0-8122-1047-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Attinger, Pascal. Inana et Ebih. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie. 3 1988, pp 164–195

- ^ Karahashi, Fumi (April 2004). "Fighting the Mountain: Some Observations on the Sumerian Myths of Inanna and Ninurta". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 63 (2): 111–8. JSTOR 422302.

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961). Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.: Revised Edition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 82. ISBN 0-8122-1047-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Inana and Gudam". The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. 2003. 1.3.4.

- ^ "Inana and An". The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. 2003. 1.3.5.

- ^ Harris, Rivkah (February 1991). "Inanna-Ishtar as Paradox and a Coincidence of Opposites". History of Religions. 30 (3): 261–278. doi:10.1086/463228. JSTOR 1062957.

- ^ Kramer & Wolkstein 1983, pp. 30–49.

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 101–103. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFKramer1961 (help)

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 101. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFKramer1961 (help)

- ^ "Nergal and Ereshkigal" in Myths from Mesopotamia, trans. S. Dalley (ISBN 0-199-53836-0)

- ^ Kilmer, Anne Draffkorn (1971). "How was Queen Ereshkigal tricked? A new interpretation of the Descent of Ishtar". Ugarit-Forschungen. 3: 299–309.

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah. "Dumuzi's Annual Resurrection: An Important Correction to 'Inanna's Descent'." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 183 (October 1966:31), interpreting a newly-recovered final line as uttered by Inanna, though the immediately preceding context is incomplete.

- ^ Sandars, Nancy K. (1989). Poems of Heaven and Hell from Ancient Mesopotamia. Penguin. pp. 162, 164–5. ISBN 0140442499.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 158–162.

- ^ Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Novato, California: New World Library, 2008), pp. 88–90.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (2011). "Inanna's Descent: A Sumerian Tale of Injustice". Ancient History Encyclopedia

- ^ Clyde Hostetter, Star Trek to Hawa-i'i (San Luis Obispo, California: Diamond Press, 1991), p. 53)

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. ix-xi.

- ^ a b Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. x–xi.

- ^ http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr141.htm

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 89.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. "Inanna." Ancient History Encyclopedia. 15 October 2010. http://www.ancient.eu/Inanna/.

- ^ Marcovich 1996, pp. 43–59.

- ^ Tseretheli, Michael (1935). "The Asianic (Asia Minor) elements in national Georgian paganism". Georgica. 1 (1): 55–56.

- ^ White 2013

- ^ Hebrew review by Michal Sadan and photos of Inana paintings

- ^ Chicago, Judy. The Dinner Party: From Creation to Preservation. London: Merrell (2007). ISBN 1-85894-370-1.

- ^ "Inana and Ebih". The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. 2001. cited in Anne O Nomis (2013). "The Warrior Goddess and her Dance of Domination". The History & Arts of the Dominatrix. Mary Egan Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 9780992701000.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ See "A Hymn to Inana (Inana C)". The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. 2006. lines 70–80. cited in Anne O Nomis 2013, pp. 59–60 Dominatrix Rituals of Gender, Transformation, Ecstasy and Pain

Bibliography

- Baring, Anne (1991), The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image, London, England: Viking Arkana

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary, University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-70794-0

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Enheduanna. "The Exaltation of Inanna (Inanna B): Translation". The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. 2001.

- Frymer-Kensky, Tikva Simone (1992), In the Wake of the Goddesses: Women, Culture, and the Biblical Transformation of Pagan Myth, Free Press, ISBN 0029108004

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fulco, William J., S.J. "Inanna." In Eliade, Mircea, ed., The Encyclopedia of Religion. New York: Macmillan Group, 1987. Vol. 7, 145–146.

- George, Andrew, ed. (1999), The Epic of Gilgamesh: the Babylonian epic poem and other texts in Akkadian and Sumerian, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-044919-1

- "Inana's descent to the nether world: translation", The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford, 2001

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1976), The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-02291-9

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kramer, Samuel Noah (28 April 1970), The Sacred Marriage Rite, Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0253350350

- Noah Kramer, Samuel (1988), History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Recorded History (3rd ed.), University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0-8122-1276-1

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961), Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.: Revised Edition, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-8122-1047-6, retrieved 26 March 2017

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963), The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-45238-7

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Leick, Gwendolyn (2013) [1994], Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-92074-7

- Marcovich, Miroslav (1996), "From Ishtar to Aphrodite", Journal of Aesthetic Education, 39 (2): 43–59, doi:10.2307/3333191, retrieved 30 April 2017

- Mitchell, Stephen. Gilgamesh:A New English Translation. New York: Free Press (Div. Simon & Schuster), 2004.

- Stuckey, Johanna (2001), "Inanna and the Huluppu Tree, An Ancient Mesopotamian Narrative of Goddess Demotion", in Devlin-Glass, Frances; McCredden, Lyn (eds.), Feminist Poetics of the Sacred, American Academy of Religion, ISBN 978-0-19-514468-0

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Van der Mierop, Marc (2007), A History of the Ancient Near East: 3,000–323 BC, Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-4911-2

- White, Gavin (2013), The Queen of Heaven. A New Interpretatation of the Goddess in Ancient Near Eastern Art, Solaria, ISBN 978-0955903717

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983), Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer, New York City, New York: Harper&Row Publishers, ISBN 0-06-090854-8

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Santo, Suzanne Banay (15 January 2014), From the Deep: Queen Inanna Dies and Comes Back to Life Again, Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Red Butterfly Publications, p. 32, ISBN 9780988091412

Further reading

- Black, Jeremy (2004). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926311-0.

- "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford. 2003.

- Halloran, John A. (2009). "Sumerian Lexicon Version 3.0".

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Voorbij de Zerken: a Dutch book which "contains" both Ereshkigal and Inanna.

- Pereira, Sylvia Brunton (1981). Descent to the Goddess. Inner City Books. ISBN 978-0-919123-05-2. A Jungian interpretation of the process of psychological 'descent and return', using the story of Inanna as translated by Wolkstein & Kramer 1983.